Why do we have Steadman Buildings section on Joseph Henry Project? Joseph Henry House, the residence of Joseph Henry in the period of 1838-1846, was built by Steadman. Furthermore, Steadman has been responsible to many buildings in Princeton city and has been described to “transform Princeton from a brick and stone village into a New-England-style town of wood and classical influences.”

Charles Steadman – The Builder

Steadman, Charles (1790-1868) was an architect-builder. Nothing is known of Charles Steadman’s early life, except that he was born in Massachusetts and arrived in Princeton by 1813. Beginning as a carpenter, he established himself as the town’s leading architect-builder. His style incorporated Federal (see Wikipedia) and Greek Revival (see Wikipedia) elements. Among his surviving works are several houses on Alexander, Stockton, and Mercer streets. A house he built at 72 Library Place was once the residence of Woodrow Wilson. He also was responsible for Miller Chapel at the Princeton Theological Seminary (1833-1834). The proportions of Steadman’s buildings are pleasing, and he was adept at utilizing motifs from pattern books. Nevertheless, the facade of his most outstanding building, the Nassau Street Presbyterian Church (1836), came from the drawing board of Philadelphia architect Thomas U. Walter. Steadman worked in Princeton until 1865, but then moved to Yonkers, New York, where he died.

Princeton Architecture

Princeton Architecture

Three authors, Greiff, Gibbons and Menzies authored a book entitled Princeton Architecture. We have scanned a few pages of the book where Steadman’s buildings are mentioned. Below is direct quote from the book.

Here are the descriptions from the book about Charles Steadman:

With the exception of the work of Latrobe and John Haviland, on the college campus, to speak of early nineteenth-century architecture in Princeton is to study the work of Charles Steadman. As a businessman he flourished in this prosperous era, and, more important, as a builder-architect he marked Princeton with the indelible stamp of this national style of architecture. Steadman was born in 1790; we know nothing of his early life, but he was in Princeton in 1813 when money was subscribed to him for losses sustained in a fire. By 1820 he was employed by the First Presbyterian Church as a carpenter and had already become a solid citizen, for he was also a member of the fire company. Three years later, as assistant alderman, he made plans for a Town Hall.

By the third decade of the century Steadman was a successful and respected member of the community, partner in a lumberyard and drygoods business. As entrepreneur, he became Princeton’s first real estate developer, buying up large blocks of land, subdividing them and building houses, which he then rented or sold. In the style of modern developers, he named one of the streets he opened after himself. As a man of property, Steadman played an active role in community affairs. He was at various times a director of the Princeton Bank, a trustee of the Princeton Preparatory School, a member of the committee attempting to organize Mercer County, a member of the building committee for Trinity Church and later its first warden and a vestryman. His business activities prospered so much that in 1835-1836 when the First Presbyterian Church burned, Steadman, who had worked for the church as a carpenter for $1.50 a day ten years before, acted both as the architect and main financier for the rebuilding. Steadman’s most active period as a builder was from about 1825 to 1845. After this time we know less of his work, but he was still a pillar of the church almost until the time of his death in New York in 1868.

John F. Hageman, who knew Steadman, wrote in his history of Princeton, “There was no architect and builder … who gave so many years and so much capital to the erection of buildings, public and private, as Charles Steadman.” Steadman was a typical carpenter-builder. Beginning as a carpenter working in the traditional methods of his time, he went on to become a self-taught builder architect, basing the designs for his buildings on a combination of his own practical knowledge and ideas he found in pattern books. His style, a mixture of both Federal and Greek Revival modes, was not great architecture; rather it was competent, practical, and pleasing to the eye in its proportions and details. The mark it has left on Princeton has done much to enhance the beauty of the town, which has never again met the consistent level of quality he maintained.

Of the more than seventy buildings attributed to Steadman, about forty are extant. One of the earliest still standing is 12 Morven Place, built before 1830. It was moved to its present site in 1905 from its original position to the west of the First Presbyterian Church. 12 Morven Place is traditional in preserving the four-square plan of the Georgian house, but differs from its colonial predecessors in proportion. The ceilings are higher, while the roof is not as steeply pitched. The combined effect of these changes is to make the façade of the house seem very square and to stress the geometric volume of the cubic mass behind the façade. In decorative detail the builder has turned to classical sources, derived from the pattern books of architects such as Minard Lafever or Asher Benjamin.

His skill and freedom in handling this vocabulary is apparent in the well-carved floral motifs around the front door and the modified Roman Ionic capitals which support the roof over the single-storied portico. The windows flanking the door and directly above it are divided into three lights separated by thin pilasters and crowned with projecting lintels. These windows together with the freestanding columns of the portico and the carved doorway, give the façade a sculptural quality in which light and shade play an important part, creating a rich contrast between mass and void. The effect is quite different from flatter, more linear eighteenth-century facades.

A more elegant and perhaps even earlier example of Steadman’s work is Borough Hall on Stockton Street. This house, opposite Morven, was built shortly after 1825 by Richard Stockton, the “Duke,” for his daughter Annis on her marriage to Senator John Renshaw Thomson. Later alterations notably the mansard roof, have robbed the building of some of its classic simplicity, but it still has a grand ballroom, finely detailed windows, impressive yet delicate four columned portico, and rich black marble fireplaces, which may have been brought from New York. The handling of the details and the proportions of the building project lightness and elegance rather than heavy solemnity.

In Steadman’s later buildings one notices an increasing compactness, monumentality, and more restrained use of detail. 72 Library Place, one of Woodrow Wilson’s former residences, is a five-bay house in which the decoration is confined to the front door, the window directly above and the cornice, the latter impressively terminating and unifying the whole façade. The play of light and shadow is increased by the carving, which is more deeply incised than that of his earlier buildings.

The more characteristic, because more modest, Steadman house of the 1830s’s has three bays, with side entrance, in plan much like a New York of Philadelphia town house of the same period. Among the best examples are several on Alexander Street and Mercer Street. They may have been built on speculation and were most certainly occupied by local tradesmen. Together the group constitutes a remarkable survival of an early nineteenth century middle class neighborhood. As such, the whole complex could serve as a model to today’s developers, a visual dissertation on how to achieve variety and preserve good taste, while working within the confines of almost identical plans and lots. Though not large, these Alexander Street houses have a certain monumentality, derived from their compact cubic shape combined with solid, well-ordered classical detail and proportion. As a group they are unified by repetition of motifs, the number and spacing of the windows, and the relation of the portico to the façade. At the same time Steadman skillfully achieved variety by varying details within each house. The graceful round columns of No. 29 (look at the PDF file) are juxtaposed to the square piers of its neighbor; the rectangular garret windows of No. 31 contrast with the beautiful scalloped molding of No. 29.

A tantalizing description in the Princeton Whig of 1836 advertised for sale at auction in New York, “ … that elegant and Classic Grecian Doric Villa and Lot, in Princeton” and went on to describe the house, which included a bathroom with “accommodations for cold, warm, and shower baths.” The inclusion of indoor bathing facilities was symptomatic of a concern for the household’s convenient operation, of a trend toward the provision for solid comfort that would come to full flower in the Victorian era. If the advertisement had read “Ionic” instead of “Doric” the house in question could reasonably be identified as Drumthwacket, built about 1835, probably by Steadman. If indeed Steadman did build Drumthwacket, it was the most elegant of his private homes. Generally he used conservative designs for houses, restricting himself to a classical vocabulary applied to individual elements of the design – doors, windows, cornices. Drumthwacket is an exception. The entire façade is bound together by the colossal portico, embracing the full height and width of the building. The refined use of the anthemion and other classical motifs both inside and out, and the cubic monumentality of the building place it in a very different class from the simple houses of Alexander Street. Possibly the more elaborate program of Drumthwacket expressed the wishes of the architect’s client, Charles Smith Olden, who had returned to his native Princeton from New Orleans in 1834 in possession of a considerable fortune. Undoubtedly in New Orleans he had admired the ample, porticoed, classic mansions then being erected by men of wealth in the Garden District and on the outlying plantations.

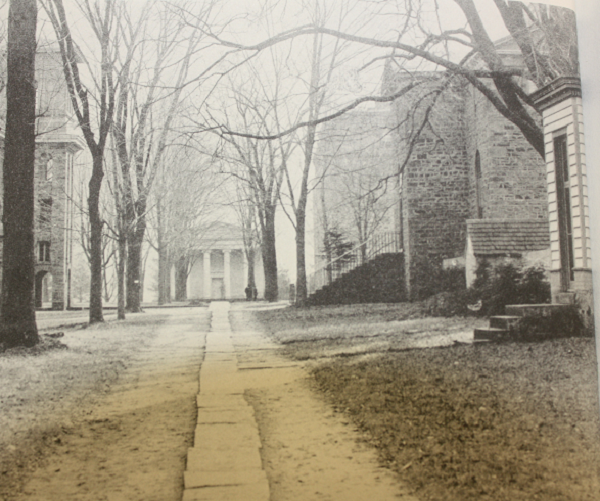

With the exception of Drumthwacket, Steadman reserve the more monumental and obviously classical temple types for his public buildings. Of those built in the 1830’s, Princeton has two notable survivals: Miller Chapel at the seminary, erected in 1833, and the First Presbyterian Church rebuilt by Steadman in 1835-1836. In these buildings Steadman had two of his rare opportunities to produce full-blown Greek Temple types so much in vogue at the time. Miller Chapel, although small, is monumental in feeling, a quality it derives from its formal Doric portico, its severe simplicity of outline, and restrained use of decorative detail. In their use of classical details builder-architects like Steadman did not slavishly reproduce in antiquarian fashion the antique models. They used them with a freedom and often naivete which made their work uniquely expressive of early nineteenth-century America.

The First Presbyterian Church on Nassau Street, while monumental and massive in proportion, is less severe than the Chapel. The curving Ionic capitals of the fluted columns and the egg and dart detail on the pilasters of the façade give it a more refined and regal appearance than its smaller sister. The church is especially important as a very early example of the in antis type of façade; that is, two free-standing columns on a recessed porch enclosed by two projecting side blocks framed by coupled antae, or pilasters, at the corners. This design, which had first been employed in New York four years earlier, was to become a staple of American church architecture.

Steadman also executed the original buildings of the Halls, Whig and Clio, based on designs by the Philadelphia architect, John Haviland. Steadman’s other major designs were for the original Trinity Church and Mercer Country Court House (both destroyed), the first Princeton Bank building, and probably for the First Presbyterian Church in Trenton.

Fortunately, Steadman used the temple form only where appropriate and refrained from the excesses often found in other parts of the country where Greek temples became canonic regardless of function. Perhaps the panic of 1837 helped curb an inordinate use of the temple form by slowing business activity in Princeton to a crawl. In the words of John F. Hageman, “The great financial revulsion in 1837, which spread so much desolation throughout the States, by depreciation of property and general bankruptcy, affected Princeton much, though not so much as it did many other communities.” Nevertheless, in a little more than a decade, Steadman had succeeded in changing the face of Princeton. Colonial Princeton was primarily a red brick and stone village. It is Steadman’s early nineteenth-century town, its placid streets lined with classically ordered white clapboard houses, that has dominated the popular image of “old Princeton.”

Steadman’s Works

Palmer House (1824)

Mrs. Zilph Palmer bequeathed Palmer House to the University in 1968. She was the widow of Edgar Palmer ’03, the alumnus who gave Palmer Stadium and Palmer Square to Princeton.

Mrs. Zilph Palmer bequeathed Palmer House to the University in 1968. She was the widow of Edgar Palmer ’03, the alumnus who gave Palmer Stadium and Palmer Square to Princeton.

Charles Steadman, a local architect who built many well-known houses in the community, built the house circa 1823–24. Despite knowing who the builder is, the architect is still not known as the design is too sophisticated to attribute to Steadman. The original owner was Commodore Robert Stockton (1795-1866), grandson of the signer of The Declaration of Independence. He married Maria Potter of Charleston, South Carolina and they received the house as a wedding present from her father, John. When Robert moved across the street into “Morven,” the old Stockton homestead, he sold Palmer House to his brother-in-law, James Potter. (Later he built “Lowrie House” down Stockton Street for one of his children while his older brother-in-law, Thomas Potter, built “Prospect House” on the south side of the campus – both designed by John Nottman of Philadelphia.

Subsequently, the Potter family sold the house to the Garretts of Baltimore. Robert Garrett ’97 was a Trustee of the University with a particular interest in its grounds and buildings. He was Princeton’s first Olympian, having won a gold medal his junior year when the Olympic Games were revived in Athens. His name is also honored in the Library, which houses his collection of Near Eastern manuscripts, and in the Great North Window of the Chapel. In 1923, he sold the house to Edgar Palmer.

Little of the façade has been changed since then but, of course, there have been changes inside. For example, the Palmers made a big Drawing Room by combining two rooms. Much of the furniture in the house is from the University’s collection. Mrs. Palmer’s heirs left a few items namely in the dining and front bedrooms. Others came from old houses on the campus and from the Princeton Inn. Some were bequeathed to the University in former years and some, like the 18-century grandfather clock in the Parlor foyer, were given recently be Edward O’Neill ’31 of Pittsburgh.

12 Morven Place (Before 1830)

Built prior to 1830 on a lot directly to the west of the First Presbyterian Church, it replaced the stone tavern that occupied the site in the eighteenth century. The house was moved to its present location in 1905. Distinguished occupants have included Professors Stephen Alexander and Albert M. Dod. Steadman was already using a mixture of Roman and Greek vocabularies when he designed this facade. He had abandoned the elliptical motifs, favored in the Federal era, for rectangular forms, but the slenderness of the columns is reminiscent of the taste of a decade earlier. The wrought-iron fence in the foreground was originally erected in 1838 as the boundary between Nassau Street and the college campus fronting Nassau Hall. When FitzRandolph Gateway replaced it in 1905, the fence was moved to the grounds on the Second Presbyterian Church (St. Andrew’s) at Nassau and Chambers Streets. During a restoration of the church in 1965, it was once more taken down and moved to its present site

Alexander Street (1834)

First named Canal Street, the street linked Princeton with the Delaware and Raritan Canal, which along with the railroad stimulated growth throughout the town in the 1830s. Charles Steadman, a local architect/carpenter, subdivided the land in the 1830s and 1840s and constructed houses, decorating the doorways and cornices using motifs from published pattern books. At the height of its activity Canal Street was a lively commercial center that included two basins where barges could load and unload, a railroad station, haypress, iron roofing manufacturer, sash and blind factory, and a hotel. The poet T. S. Eliot stayed at 14 Alexander Street in the fall of 1948, while he was a visiting fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study.

First named Canal Street, the street linked Princeton with the Delaware and Raritan Canal, which along with the railroad stimulated growth throughout the town in the 1830s. Charles Steadman, a local architect/carpenter, subdivided the land in the 1830s and 1840s and constructed houses, decorating the doorways and cornices using motifs from published pattern books. At the height of its activity Canal Street was a lively commercial center that included two basins where barges could load and unload, a railroad station, haypress, iron roofing manufacturer, sash and blind factory, and a hotel. The poet T. S. Eliot stayed at 14 Alexander Street in the fall of 1948, while he was a visiting fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study.

Miller Chapel (1834)

Named for Princeton Seminary’s second professor, Samuel Miller, the building that is the spiritual center of the campus has been in continuous use by the Seminary community for worship since it was completed in 1834. Originally designed by local architect Charles Steadman, the original building has been renovated four times – in 1874, 1933, 1964 and most recently in 2000. It encompasses a ‘one-room’ worship space uniting celebrants, choir and congregation. The central pulpit emphasizes the centrality of the proclaimed Word of God in the Reformed tradition. Miller Chapel is home to the Joe R. Engle Organ, which was a gift to Princeton Seminary in 2000.

Named for Princeton Seminary’s second professor, Samuel Miller, the building that is the spiritual center of the campus has been in continuous use by the Seminary community for worship since it was completed in 1834. Originally designed by local architect Charles Steadman, the original building has been renovated four times – in 1874, 1933, 1964 and most recently in 2000. It encompasses a ‘one-room’ worship space uniting celebrants, choir and congregation. The central pulpit emphasizes the centrality of the proclaimed Word of God in the Reformed tradition. Miller Chapel is home to the Joe R. Engle Organ, which was a gift to Princeton Seminary in 2000.

In addition to worship services, Miller Chapel is also the locale for various concerts hosted by the seminary throughout the year, including numerous concerts performed by the Seminary Choirs. The basement of Miller Chapel houses rooms for Spiritual Direction, a classroom and the vestry.

Nassau Presbyterian Church (1836)

In 1751 Princeton residents petitioned the New Brunswick Presbytery to build their own meeting house, and the original structure was completed in 1764. The church burned down twice, once in 1813, and again in 1835. The structure at 61 Nassau Street in its present Greek Revival style was dedicated the following year. Charles Steadman designed the church using a facade plan purchased for $10.00 from Philadelphia architect Thomas U. Walter. David Peterkin, a local tombstone carver, executed the carving for the capitals and bases of the front columns. In the 1840s ninety members, mostly African-American, established a new congregation at the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church.

In 1751 Princeton residents petitioned the New Brunswick Presbytery to build their own meeting house, and the original structure was completed in 1764. The church burned down twice, once in 1813, and again in 1835. The structure at 61 Nassau Street in its present Greek Revival style was dedicated the following year. Charles Steadman designed the church using a facade plan purchased for $10.00 from Philadelphia architect Thomas U. Walter. David Peterkin, a local tombstone carver, executed the carving for the capitals and bases of the front columns. In the 1840s ninety members, mostly African-American, established a new congregation at the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church.

Woodrow Wilson Houses (1836)

In addition to Prospect, Woodrow Wilson occupied three houses during his time in Princeton: 72 Library Place, 82 Library Place, and 25 Cleveland Lane (the picture above is 72 Library Place). Graduating from Princeton in 1879, Wilson served as professor of law from 1890 to 1902, and as president of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, during which time he revolutionized the school’s curriculum and teaching system. He was Governor of New Jersey between 1910 and 1912 and President of the United States between 1913 and 1921. The house at 72 Library Place was built in 1836 by Charles Steadman, and acquired by Woodrow Wilson in 1889. Wilson commissioned New York architect Edward S. Child in 1895 to design the Tudor Revival house at 82 Library Place.

In addition to Prospect, Woodrow Wilson occupied three houses during his time in Princeton: 72 Library Place, 82 Library Place, and 25 Cleveland Lane (the picture above is 72 Library Place). Graduating from Princeton in 1879, Wilson served as professor of law from 1890 to 1902, and as president of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, during which time he revolutionized the school’s curriculum and teaching system. He was Governor of New Jersey between 1910 and 1912 and President of the United States between 1913 and 1921. The house at 72 Library Place was built in 1836 by Charles Steadman, and acquired by Woodrow Wilson in 1889. Wilson commissioned New York architect Edward S. Child in 1895 to design the Tudor Revival house at 82 Library Place.

Joseph Henry House (1838)

In 1832 Joseph Henry came to Princeton University as a professor of natural philosophy. Henry, best known for his discovery of the electromagnetic phenomenon of self-inductance, built a large magnet at Princeton, which could lift 3,500 pounds. In 1846 he left Princeton to become the first secretary and director of the new Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. The house, probably designed by Joseph Henry, was built in 1838 and was moved three times before being set in its present location. House moving has been a common occurrence in Princeton since the 18th century and at least 100 houses in the town have been moved.

In 1832 Joseph Henry came to Princeton University as a professor of natural philosophy. Henry, best known for his discovery of the electromagnetic phenomenon of self-inductance, built a large magnet at Princeton, which could lift 3,500 pounds. In 1846 he left Princeton to become the first secretary and director of the new Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. The house, probably designed by Joseph Henry, was built in 1838 and was moved three times before being set in its present location. House moving has been a common occurrence in Princeton since the 18th century and at least 100 houses in the town have been moved.

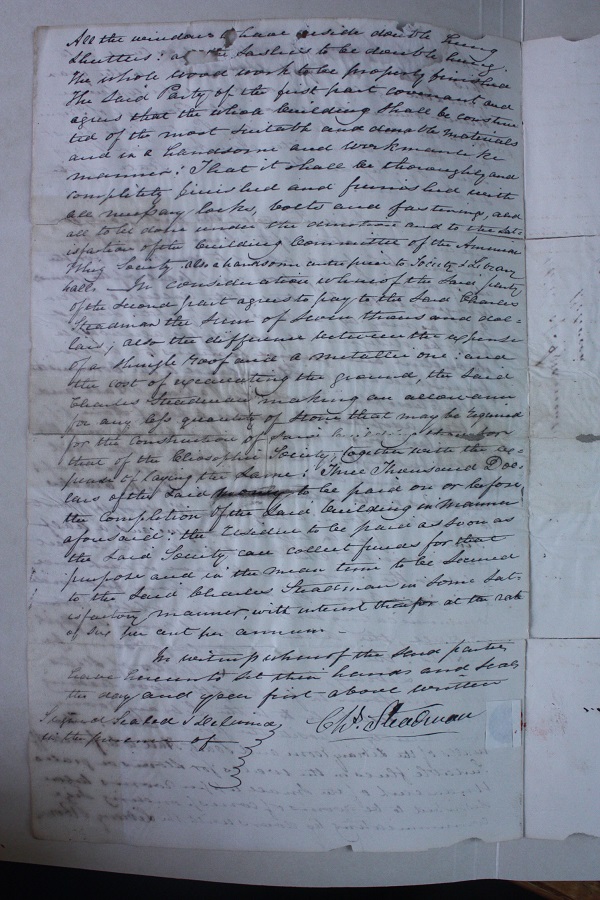

Whig and Clio (started in 1837)

The buildings on the modern Princeton campus known as Whig and Clio are not the first to bear these names. The structures that stand today are 1890s recreations (and embellishments) of the ones built for the debating societies in the late 1830s. In turn, the story of the original Whig and Clio reflects the importance of these societies in undergraduate life as well as the dominance of the Greek Revival style in that period. Some believe that the Societies, with Clio following Whig’s lead, commissioned the prominent Philadelphia architect John Haviland to design their new Halls. Haviland is best known for designing the monumental “Tombs” prison in New York. Others believe that the local builder/architect Charles Steadman produced the design. Steadman’s work continues to be visible in the Princeton area, particularly on Alexander Road. Constance Greiff, local architect historian, clauns that Haviland designed the original Clio Hall and Steadman built it. Steadman then turned around and built a replica for Whig.

Bitter rivals, the American Whig Society and the Cliosophic Society dominated undergraduate life at the College of New Jersey during the late 18th and most of the 19th centuries. The Halls, as they were known, were independent entities that combined the best and worst elements of secret society, debating club, social center, library, and political organization. As with the eating clubs of a later generation, Whig and Clio were often a thorn in the side of the College administration. In the 1820s, for example, many of the leading members of the politically liberal Whig Society were expelled for leading demonstrations against the College. It was only one of many incidents of student unrest in this period. At the same time, however, the Halls enjoyed powerful alumni support and provided services that the College did not. During parts of the Carnahan era, for example, the College’s Library was only open one hour a week. By contrast, the Halls maintained fine private libraries and collections of periodicals. The comparative sizes of the Hall’s libraries versus the College’s can be traced in the description of each in the College’s Catalogues. Both Societies were originally housed in Nassau Hall. After the fire of 1802 and the completion of Geological Hall, they moved into contiguous rooms in the new building. By the 1830s, both societies had outgrown their cramped quarters; what’s more, their rooms were altogether too close for these secretive and competitive bodies. In 1835, the Whig Society organized a building committee to consider building their own separate new structure. The Clios followed soon after. Representatives of the Societies approached the Trustees in September of that year, and in September 1836 both Societies were granted permission to build Halls — at their own expense — in the locations indicated on Joseph Henry’s plan.

Today, the two Greek Revival temples seem somewhat out of place amidst the Collegiate Gothic of the Princeton campus. But in the late 1830s, when these structures were first erected, they represented the height of architectural fashion. The reference to classical Greek structures was an appropriate gesture by societies that existed to promote “democratic” debate. Together, the two temples anchored the southern end of the rear campus, creating the quadrangle that would later become known as Cannon Green. As seen in contemporary photographs, Whig and Clio were much farther apart than they are today; as originally built, both were visible from Nassau Street, on either side of Nassau Hall. There were good reasons to separate the two as far as possible. Jealous of their privacy, the Societies at one point even reached a “treaty” whereby members of the opposite hall were forbidden to sit on the steps of the other Society, nor to approach within 20 yards when the other was in session.

Whig and Clio were built at the same time. The cornerstones were laid in Summer 1837 and both buildings were first occupied by the Societies in 1838. For all their classic appearance, the original Halls were elaborate fakes. Rather than being constructed of marble, they were fabricated of brick, wood, and stucco — and lots of white paint. This kept the cost to roughly $7,500. The only discernible architectural difference between the two seems to have been a watertable that was added below Whig’s downstairs windows in an attempt divert rain from running down the walls of a building and eroding the foundation. (Contrast this with Clio.) The Halls continued to play a prominent role in the social and intellectual life of the campus through the turn of the century. A diagram of the floor plan of the first Whig, for instance, suggests a fine facility with a spacious library and reading room downstairs and a large assembly room on the second floor. Whig, which tended to attract more affluent students, was especially luxuriously appointed inside. As another indication of the power of the Halls at this point in the College’s history, the main meeting rooms in both buildings were the largest indoor spaces on the campus, except for the Prayer Hall in Nassau Hall. The College itself never commissioned a full-blown Greek Revival building. The town of Princeton has its share — the First Presbyterian Church on Nassau Street is an outstanding example of the style. Compared to many other colleges and universities, the Princeton campus was only lightly touched by this architectural movement.

Charles Steadman built these houses at 40 and 42 Mercer Street for his two daughters in the 1830’s.

Bibliography

Greiff, Constance M., Mary W. Gibbons, and Elizabeth G. C. Menzies. Princeton Architecture: A Pictorial History of Town and Campus. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U.P., 1975. Print.

Haviland, John, and Hugh Bridport. The Builder’s Assistant. Philadelphia: John Bioren, 1818. Print.

“Jenzabar University.” Chapel Office. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 June 2013.

Levin, Anne. “The Master Builder.” Princeton Magazine Feb. 2013: 60-63. Web. 1 July 2013. <http://issuu.com/witherspoonmediagroup/docs/finaljanfeb2013>.

“Princeton’s Historic Sites and People.” Historical Society of Princeton. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 June 2013.

“Steadman, Charles To Stevens Institute of Technology (New Jersey).” Whatwhenhow RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 June 2013.

“Welcome to Palmer House.” Welcome to Palmer House. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 July 2013.