The Vacuum Effect

The story of Stetson Hospital and healthcare’s disappearance from Kensington, Philadelphia

The John B Stetson Hat company once had a staggering 25 building campus in Philadelphia, primarily concentrated in the Kensington neighborhood. Now, in 2021, only a handful of these buildings remain standing. The physical destruction of many of the Stetson buildings not only represents the changing material culture of the products we consume in the United States but also the intimate relationships between the community and the companies that provided for them. While the Stetson hospital building still stands in Kensington, the relationships it once exemplified and cultivated are gone. Pat’s story, describing the change in healthcare dynamics and access in the Kensington neighborhood as she witnessed the rise and fall of the Stetson company shows that the presence of a building, and calling it a hospital, does not equate to healthcare. Rather, absence is felt not in the demolition of the physical space but in the missing relationships and personal connections to care that now affect the Kensington neighborhood.

In order to analyze the story of structural violence and its embodiment in the current Philadelphia population, it is necessary to assess what was both present and not present at different times in history. The story of the Stetson Hat factory, and specifically its hospital, provides a valuable perspective on the community-level impact accessible health care ensures. This specific story provides an example of how absence caused by structural violence is both physical and metaphorical; the summation of the hidden relationship of a community to healthcare in our society with vacant, historical buildings yields a vacuum.

Motivating Thoughts and Questions

Philadelphia’s Riverwards, once a section of Philadelphia’s “Northern Liberties”, were communities that developed an isolated, symbiotic relationship with many of the privately-owned manufacturing plants in the area. These relationships arguably formed out of necessity, as the Northern Liberties were on the outskirts of the city they did not have the same government infrastructure. Because they supported themselves within the immediate community, there was not much community-level need for governmental intervention in terms of organization, programming, and infrastructure. The relationship was weighted the opposite way: Philadelphia engulfed the Northern Liberties because of the region’s economic power. The Northern Liberty communities, specifically Kensington, were referred to as “the Workshop of the World.”

It is arguable, that because the geographic region of the Riverwards created their own internal community infrastructure (specifically in reference to healthcare), that there was a historical absence of governmental funds and support due to the presence of private companies. However, if this was indeed the mindset occurring in the mid to late 1800’s, could this have led to decreased governmental connection and trust with modern Philadelphia’s most vulnerable communities?

Understanding the Microcosm of the Riverwards

That community lost a lot when Stetson closed, a lot. And the void hasn’t been filled. -Pat Orphanos

Pat Orphanos is the daughter of one of the last physicians to practice medicine in the Stetson Hospital. In my conversation with Pat, she made clear two points about the history of healthcare in Philadelphia:

- The absence of a community healthcare center, notably the Stetson hospital, in neighborhoods such as Kensington has proved harmful to the population.

- The transition of the medical industry from personalized medicine to medicine-as-a-market, with Big Pharma and health insurance companies, has ruined the standard of care and physicians as a whole.

Pat’s valuable perspective provides ethnographic knowledge from her experiences growing up and interacting with the community healthcare system in Kensington while additionally reflecting on the periods from the 1950s to the present, in which the dynamics of our healthcare system have shifted drastically.

During our conversation, Pat’s explicit mentioning of the subject emphasized to me that her ties to the Stetson company were a source of pride. She showed me numerous memorabilia from the company, like war-time posters, the monthly employee magazine, and hat boxes. One could tell from these products that Stetson had an integral presence in the Philadelphia community and the United States as a whole. This image depicts an example of the “Keep It Under Your Stetson” campaign, which premiered in the 1940s during World War II. The Stetson hat in the country’s propaganda showed how the Stetson hat was more than an accessory- it was a cultural symbol of America.

Pat told me how the Stetson campus practically formed its own city with the amenities it offered. As the largest hat factory in the world at the time, the Stetson company had its own bank, church, athletic fields, and hospital.

The presence of a hospital marked Stetson not only as an entrepreneur but also a pioneer in healthcare for his employees; they received free care from their clinic, dispensary, and hospital. Stetson provided for more than just his company’s staff; as Pat stated, “Stetson was the place to go” for any community member not employed by Stetson, but still wanting healthcare access. Anyone could be seen in the hospital for a small fee. Pat’s father was one of the Stetson hospital physicians; he was an Albanian immigrant and completed his medical residency as a general practitioner at Stetson.

Watch and listen to this clip below, in which Pat surfaces the historical relationships which Stetson cultivated. While they are now absent, they live on in her words and memories.

Pat’s descriptions of the healthcare that occurred within the walls, and in the surrounding homes, of Stetson hospital emphasized that health was a community ordeal; everyone in the neighborhood had access, clinic hours were scheduled around the factory worker’s day hours, and the staff at the hospital treated each other as family members. The cultural dynamics at Stetson hospital emphasized health for health’s sake, rather than health for the healthcare industry’s profit.

Pat’s anecdotes provide a lot of historical, ethnographic knowledge about the degree of connectivity between the hospital and the surrounding community.

Specifically, from her father’s descriptions, you can tell that Pat and the Philadelphia community thought very highly of the medical professionals connected to Stetson. Pat utilized numbers to convey the quantity of the individuals her father impacted but emphasized numerous times throughout her interview that qualitative care was of the utmost importance. Her father treated every individual as family (versus just another patient, or just another number).

For example, Pat described two instances:

My dad had patients in a family; there was seven kids, one of the sons died in the Vietnam War, and the family used the insurance money to give their one daughter a beautiful wedding. My parents were invited and [this family] were very poor people, my father used to find jobs and things for the father. But anyway, they went and there’s my mom had a picture of my mom and dad sitting and

there were 67 people surrounding them and my father had delivered every single one of them.

Additionally,

When my when my dad passed away in ’78 the funeral procession was almost a mile long, thousands of people came to my father’s funeral because he was the neighborhood doctor; everybody in that area knew who my dad was.

Unfortunately, the family dynamic cultivated by the Stetson hospital no longer remains. Its absence is replaced with barriers to health, like the opioid epidemic.

The Vacuum Effect

People don’t understand what’s lost. -Pat Orphanos

Pat’s stories of the large-scale, community presence of the Stetson hospital provide ethnographic knowledge for why the Philadelphia government did not need to invest in the Northern Liberties early in its development. These neighborhoods functioned as a microcosm, with structures such as healthcare support available, loan financing from employers, and a tight-knit community feel with employees living within walking distance from the factories that employed them. Not only did they have the resources available, but they were well cared for on a very personal level. As Pat said, “everyone knew everyone,” and her father even ensured that those who were too old, feeble, or poor to afford modest-priced healthcare were given personal, accessible options.

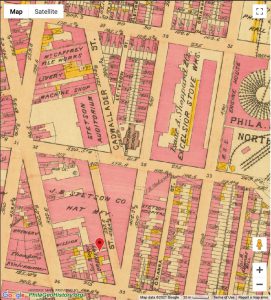

However, hard times hit the Stetson company starting in the 1950’s, when societal attire shifted away from wearing the large, dramatic hats that Stetson produced. Drastic changes occurred in the present Kensington neighborhood when the Stetson company officially shut its doors in 1971; by then, the company employed over 5,000 people, and its campus amassed 1,400,000 square feet of floor space in its buildings (“John Stetson Hat Company, Philadelphia Pennsylvania” n.d.). The map below visualizes these changes. It depicts the disappearance of those employed by the textile industry from 1960 to 1970, which happens to coincide with healthcare’s disappearance in Kensington (Social Explorer data).

When deindustrialization hit the United States after World War II, and significantly this area, not only did these communities lose their jobs and source of income, but additionally the other amenities that characterized their communities such as healthcare, education, and loan support that their employers provided. Even today, the absence was incredibly impactful because there was no previous government support or relationship in these neighborhoods. After all, companies such as Stetson had set a precedent for privatized healthcare through employment.

You know it’s a shame, and like I said, John B Stetson was such a pioneer. You know, to give care. The care to his employees was free.

Additionally, as time passed, there was little hope for government intervention due to the societal events of the time. The Great Depression hit the United States in 1929, which rendered approximately 25% of the population without jobs, the wants and needs of the greater population shifted away from the niche goods that the Riverwards specialized in during the age of deindustrialization, and neoliberal mindsets such as de-regulation emerged especially during the Reagan presidency.

One notable point to draw attention to is that new technologies rendered older versions obsolete; they also potentially contributed to Riverward manufacturing’s decline. For example, the number of individuals that owned cars steadily increased in the 20th century as the automobile industry created more accessible cars price-wise and safer roads. Specifically, with Eisenhower’s Federal Highway Act of 1956, 41,000 miles of roadways were created in the United States (“U.S. Senate: Congress Approves the Federal-Aid Highway Act” n.d.). This very well could have contributed to the decline of the Stetson enterprise, as drivers could not wear top hats in vehicles with shallow ceilings (Krulwich 2012).

Questions of Modern Day Hospital Accessibility

After concluding my conversation with Pat, one question lingered in my head: even if the Stetson Hospital remained, would current residents in Kensington have access to its’ services? Would a community-accessible hospital have made a difference in the current opioid and heroin epidemics?

One of Pat’s significant points in our conversation was the delineation between the type of healthcare services that the Stetson Hospital offered in the 1940s and ’50s versus those in modern-day hospitals. For example, she described how her father was paid in cash by the patient. Fees were based on a pay-per-visit service, and no third party such as an insurance company interfered with the payment process. Additionally, she detailed how the “logistic” aspects of medical care, like scheduling appointments, were done by the physician. She even noted that patients would call her house, and she would be in charge of writing a note for her father.

At the time, there was no such thing as “paperwork” that would require a secretary’s attention; Pat’s father managed all aspects of his practice himself, which according to Pat, was the standard of medical practice at the time. The absence of the bureaucratic aspects of medicine kept costs down for patients because of smaller staffing. Additionally, Pat described how, as a child, virtually no one held health insurance. Pat feels that it was a mere fabrication of the “need” of insurance that enabled its existence; now, many communities in Philadelphia do not have access to or cannot afford health insurance. Arguably, the inherent existence of health insurance has driven up the cost to receive medical care. Hospitals now have to employ individuals to manage all the healthcare paperwork; this, in turn, drives up the cost of healthcare to the patient to accommodate these individuals’ salaries. Pat’s discussion of insurance, expanded on in the audio clip below, highlights that in our society the presence of healthcare infrastructure does not necessarily correlate to access of care due to the barriers medical insurance now poses in neighborhoods like Kensington. Specifically, Kensington residents experiencing the health impacts of the opioid epidemic and/or homelessness are unlikely to have enough health insurance to access quality care.

Society-wide acknowledgment of the “benefits” of healthcare insurance spiked during World War II.

In 1942, with World War II causing a drastic labor shortage, employer-provided health insurance enabled employers to compete for employees when wages were frozen by the government (Carroll 2017). Technological advancements in medicine, compounded with time, resulted in more “medical problems” that physicians could diagnose. This, in turn, increased costs for patients which medical insurance was conveniently poised to “solve.”

Now, looking at the communities in Philadelphia and specifically in the Riverwards, there is a significant amount of individuals that rely entirely on government-provided health insurance (Medicaid) or have no health insurance. This is due to barriers in accessibility (such as confusing paperwork, potentially not in the individual’s native language) and in cost. Many of the employment opportunities in neighborhoods such as Kensington diminished along with the factories. The following visualizations contextualize these patterns by depicting the population that relies on Medicaid insurance (determined by income) alongside those who do not have any medical insurance as a function of time. For context, in 2015, Pennsylvania expanded its Medicaid coverage, meaning that PA constituents can qualify for Medicaid based solely on their income amount (138% of the federal poverty level). After 2015, the population receiving Medicaid increased, and the population without insurance decreased because Medicaid became relatively more available.

This following visualization depicts the same data as the previous, however, the total population affected can be visualized here as a function of time:

As with all data visualizations, it is imperative to contextualize them correctly.

These visualizations utilize Census data. It is imperative to note that many homeless individuals are not “counted” in the Census data aggregate; the majority, if not all, of homeless individuals in Philadelphia County do not have access to health insurance. Click here to view a document in the resources section that outlines the Census’s mechanisms in years past to “count” the homeless population, along with its many downfalls. This missing data would include many of the individuals who reside in the Kensington neighborhood, who would potentially interact with Stetson hospital were it present today.

While these numbers are decreasing (in terms of lack of health insurance), these numbers are not at zero; an incredible amount of individuals in Philadelphia County experience barriers to health due to insurance daily. To put these numbers into context today in the COVID19 pandemic, this means that approximately 130,000 individuals (more, if accounting for data disparities and absences) do not have access to a COVID19 test unless they can find a “barrier-free” testing location. Click here to read more about this story.

Pat’s final point

Pat told me that she feels that if her father were alive today, he would no longer be practicing medicine due to the United States’ current medical culture (click here to read more about neoliberal influences in our healthcare system). This final comment emphasized to me that not only is the healthcare infrastructure and the relationships it once expressed in the Kensington neighborhood gone, but community driven healthcare through hospitals has disappeared in our society. The dynamics of our society, acting in structurally violence ways, are taking healthcare out of the communities that need it most.