“A Theoretical Risk”

What enraged me, and probably galvanized me into activism, was the fact that the Health Department official Thomas Farley specifically said that lead in soil is a theoretical risk. -Rachel Kaminski

Just as I articulated in my introduction to structural violence, the prevalence of a problem, even if proven by data, holds little significance without societal acknowledgment. In discussing her frustrations with managing her children’s blood lead levels in Philadelphia, my conversation with Rachel revealed another example of this phenomena.

When I asked Rachel where her lead activism story starts, she referenced a 2017 report by the Philadelphia Inquirer. The article was a series of investigations pointing out high levels of lead contamination around the old Anzon site, which was located in her immediate community. Simply stated, Rachel has the belief that no one, regardless of location or history, should be subject to childhood lead poisoning.

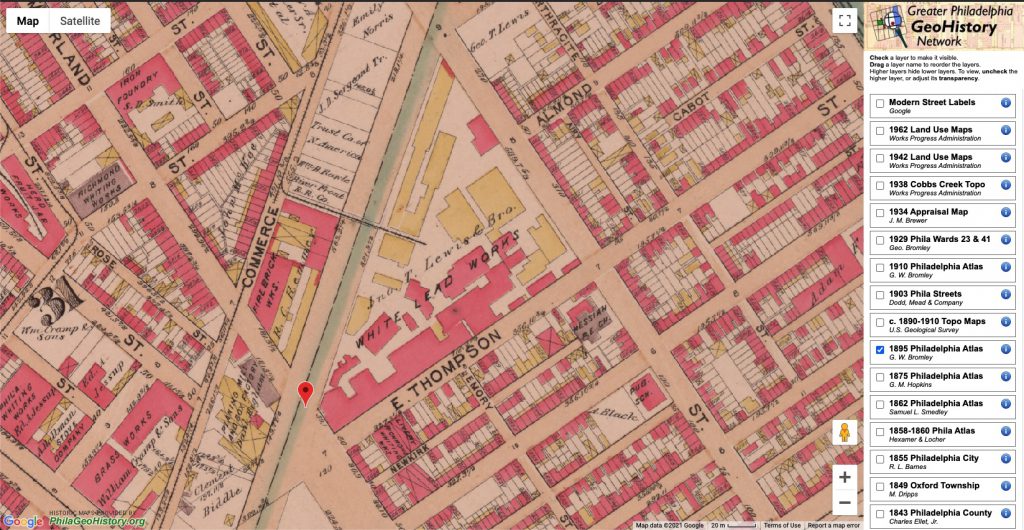

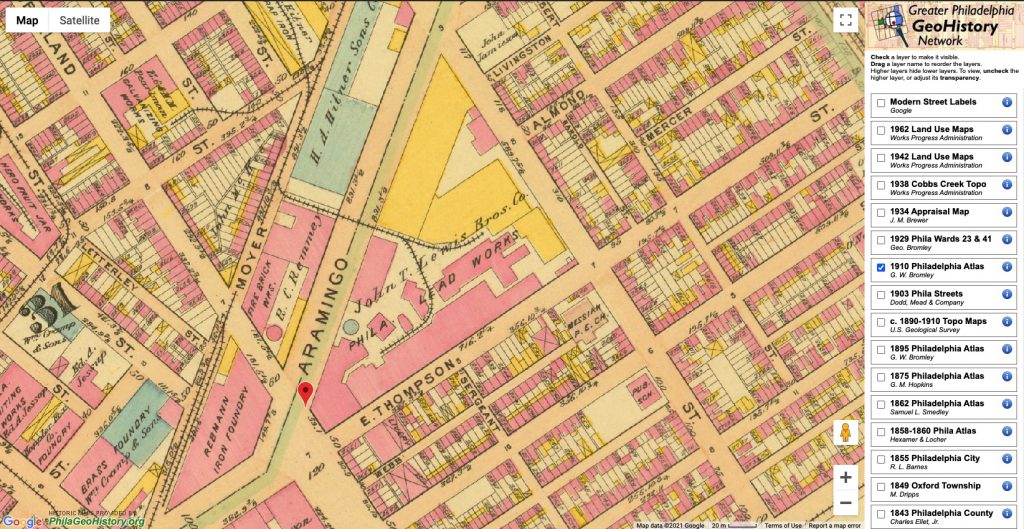

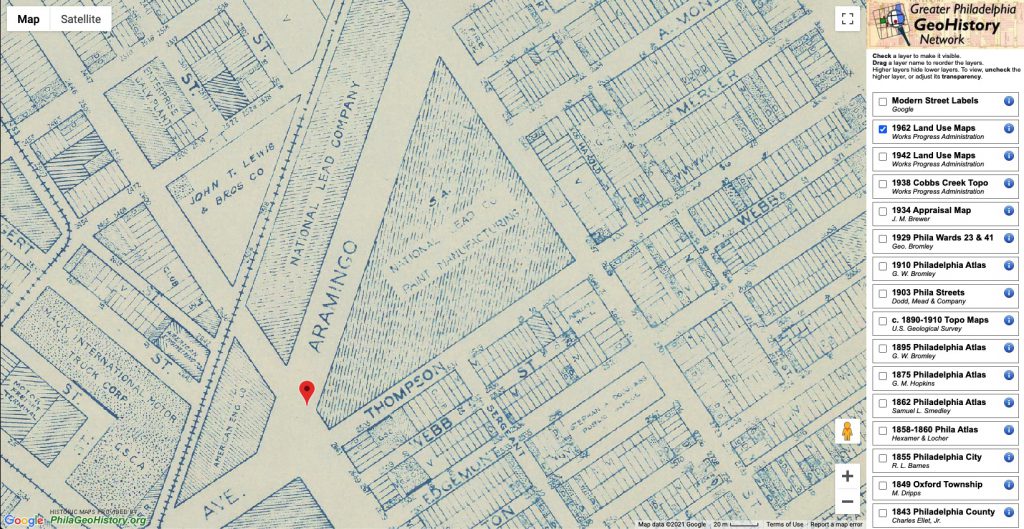

The “Anzon site” refers to the intersection of Aramingo Avenue and East Thompson Street, which is now a popular strip mall in Olde Richmond and Kensington. The geographic area is visualized in the Google map images below. Historical maps show that various metal companies have used this land for lead smelting operations since before 1862. The plant closed in the 1990s, which left over 100 years of lead pollution in the ground (Ruderman, Laker, & Purcell 2017). As depicted in the images below, highly residential areas surround the plant; this subjected its inhabitants to the smelting process’s toxic fumes. The Inquirer report cites multiple resident narratives who lived in the vicinity and routinely had to evacuate their homes when some factory chemical spill occurred (Ruderman, Laker, & Purcell 2017). In present day, when the factory closed and the area was zoned for commercial use, the developer poured cement and dirt over the toxic grounds creating a grassy patch “dubbed Mount Wawa” by residents (Ruderman, Laker, & Purcell 2017). Mount Wawa is emphasized in the picture below with the red arrow; lead samples taken from the mound for the Inquirer investigation were “6 times” the legal limit (Ruderman, Laker, & Purcell 2017).

Note: click each individual thumbnail to view full-screen.

Lead poisoning CAN occur through soil exposure

Rachel emphasized to me that one of the most frustrating things about her activism to protect children’s health in Philadelphia, is how the city’s bureaucracy has the power to invalidate your narrative. Not only do they invalidate it with words, as the Health Department official Thomas Farley did when he claimed lead in soil is only a “theoretical” risk, but also through the Health Department’s process of investigating the source of poisoning.

Rachel described how the Health Department investigates a case in which a child has over 10 mg/dL of lead in their blood. Her explanation seemed very practiced, as if she had explained the senseless process to many, many people. The order in which residences and geographic locations are tested and “determined” as the cause of poisoning is according to the list below:

- Check the lead levels of your house

- Check the lead levels of your parents’ house, your partner’s parents’ house

- Test the preschool/school that the child attends

- Test the lead levels in the soil in the backyard

The Health Department’s investigation into lead poisoning sheds light on how little lead from soil is considered a main cause of poisoning. Rachel emphasized that both the system’s process and language have rendered individuals invisible who have suffered from these real problems. Part of this issue is that there is no way to prove exactly where your child was poisoned. Lead found in the soil is molecularly the same lead found in old paint. However, a mother can employ drastic cleaning measures in her home, but not outside; this lack of control of the environment raises anxiety.

The inability to “localize lead” as originating from the soil or a specific source like a factory also proves troublesome for assigning responsibility. Because residents can’t “contact trace” lead presence due to Anzon’s lead smelting operations, they alone are left to deal with the consequences. Nobody wants to take responsibility for historical lead contamination, and children are suffering as a result.

Visualizing Blood Lead Level Data

Layering blood lead level (BLL) data from the city of Philadelphia with Rachel’s narrative is one way to investigate the dissonance between what is actually happening (narrative) and what is claimed to have occurred (data). The following visualization contains a dataset provided by the city of Philadelphia, describing the number of children tested for blood lead levels (BLL) and the percentage of children per Census tract with BLL above 5 mg/dL. It is imperative to note that 5 mg/dL is not a value determined to display a certain symptom set in children, but is a value standard determined by the CDC to only occur in the “highest 2.5% of children” in the United States (CDC).

There are some social facts that can be raised about this visualization:

- The dataset provided by the city of Philadelphia is from 2013-2015, which is severely outdated. In 2012, the CDC updated its protocols to measure blood lead levels against the benchmark of 5 mg/dL (it historically was much higher, 10 mg/dL).

- The Riverwards, which have the highest concentration of contamination sites and known lead smelters, do not (by the data) record the highest percentage of children with BLL’s higher than 5. Rather, Census tracts in Northern Philadelphia, rather than Northeastern Philadelphia, report the highest percentages. One would expect that the highest BLL percentages would be occurring in the Kensington and Fishtown neighborhoods with a geographic concentration of contamination.

- Some Census tracts do not report any data; others are unaccounted for.

It has not been standard practice for pediatricians to routinely test young children for blood poisoning until recent years (and with much urging by the activist community). Rachel said that her firstborn (born ~2015) was not tested for lead until Rachel specifically requested it. Rachel’s narrative provides insight to this data: it represents severely skewed numbers. The children represented in this dataset are most likely children who were exhibiting symptoms of poisoning or were siblings/neighbors of those who did. Additionally, many Census tracts in this visualization report no data; we are unaware of whether that means it was unreported, condensed because there were very small values, or if there is no active lead testing in these areas.

The lack of data, specifically data for recent years, surrounding childhood lead poisoning shows how little significance and attention society has given to the link between environmental contamination and health. While data is absent, the effects are very, very real. Rachel described how fellow parents in her advocacy group have children who suffer neurological impairment because of extreme lead poisoning (lead affects the brain and can result in behavior that is similar to ADHD). Children in the Philadelphia region with behavior issues may not have an attention disorder- they might have been poisoned from their own backyard.

Additionally, the basis of data and visualizations around the value of 5mg/dL shows how the presence of benchmarks can skew our perception of health-related issues. Children who report BLL’s of 2, 3, or 4 are not “free” of lead poisoning; there is no “good” level of lead in the human body, and even minuscule amounts can prove dangerous. We as a society need to reorient our focus to preventing ANY blood lead level, not just those above 5 mg/dL.

Cleaning, COVID19 Style

For many parents in the Philadelphia region, cleaning schedules, patterns, and products probably did not shift drastically with the COVID19 pandemic. This is because parents endure an enormous burden to ensure that all surfaces in the house are free from outdoor dust and potential indoor lead paint. With this consideration, lead poisoning not only affects the health of Philadelphia children, but additionally creates an atmosphere of paranoia, stress, and “mom guilt” for parents.

Think of it this way, as a list of hypothetical scenarios that Rachel outlined for me:

- If the outdoor environment that your child plays in, such as your backyard or the nearby playground, is contaminated then any object you take outdoors needs to be disinfected

- A toy could touch the ground and a child could then put it in their mouth

- A child could touch the ground and then put their fingers in their mouth

- Shoes that go outside can’t come inside

- If you use a stroller, then the stroller needs to be wiped down before coming inside

- You should avoid areas of demolition

- The stoop and windowsills need to be wiped daily

- Floors need to be vacuumed daily and the walls inspected for possible chipped paint

The amount of preventative measures is overwhelming to even think about, let alone execute on a daily basis.

Now, imagine that you execute all of the above (and potentially much more) on a daily basis, and your child still has elevated blood lead levels. This scenario happened to Rachel, who says that her oldest child has a blood lead level of 1. She described the stress and the uncertainty of the presence of an invisible toxin in her children’s environment:

They still have it, a level one; you would think that it should be zero, right? Like, it’s coming from somewhere.

The stress that parents endure to keep their children away from invisible, historical toxicity is just one example of how Philadelphia residents embody toxic environments. The term embodiment, studied and employed by medical anthropologists such as Margaret Lock, acknowledges that the human body is not simply the result of its interior genetic material but is a culmination of many external and internal forces acting upon and subsequently shaping it (Lock 2017).

External forces, in Rachel’s specific situation, could be the unrelenting presence of lead in her immediate environment and in the air from frequent demolitions. Lead as an external force co-opts many of the body’s internal processes and can impair an individual in addition to their subsequent generation. Health problems associated with childhood lead poisoning include:

- Anemia (inadequate oxygenation of the body via reduced red blood cell counts)

- Body weakness

- Kidney damage

- Brain damage, resulting in lower IQ, intellectual disabilities and behavioral problems

- Miscarriage, stillbirths, and infertility

- Neurologic developmental issues in unborn children, as lead can cross the placental barrier

- Irritability (CDC “Health Problems Caused by Lead”, 2018)

Internal forces can refer to the psychological strain and fatigue a parent or caregiver endures in fighting a battle to maintain health, which many county officials deem simply “theoretical.” These internal forces have the power to wreak havoc on the body, as chronic stress responses are associated with:

- Body ache

- Trouble sleeping

- Racing pulse

- Digestive issues

- Weakened immune system

- Depression

- Anxiety (Cleveland Clinic, 2021)

Many anthropological conversations around embodiment acknowledge that the body is not impermeable but is, in fact, co-constructed, with and without its consent, by the environment. In her piece Alterlife and Decolonial Relations, Michelle Murphy (2017) discusses how we should not view the environment as “stagnant” in reference to the “active” human body but rather an integral part of it. She asserts that we should think about molecules and chemicals not as materials produced in the past and hidden in the ground, but very much a part of the cycle by which our bodies interact with our environments. Many of the contentions Murphy points out can be applied to historic lead pollution and problems of lead poisoning in the Riverwards- especially in Rachel’s narrative. Rachel fears that many other children have blood lead levels left undetected because of a lack of testing and education, because our society’s notion of health has not yet validated the many arguments and examples of embodiment. This is seen in how compounds proven to be carcinogenic are still allowed to be ingredients in many of our society’s products. Many of Rachel’s goals in activism aim to counteract this to improve overall childhood health in Philadelphia.

There are simple, actionable solutions if people would only listen

Community and problem-specific solutions, curated and created by those most affected, have been common thread in this project. While Roz created the Community Kit to fill a void in her neighborhood, Rachel has also imagined a solution that would reduce the harm on children inflicted by past actions. She proposes to create more education programs for parents in order to foster a culture of prioritization of lead poisoning by introducing these educational programs at the right time. For example, Rachel talked about how new parents get essential information at the hospital surrounding topics such as shaken baby syndrome or nursing assistance. She feels that it is imperative to include educational materials for new parents at this early stage so that preventative measures can begin earlier rather than later.

Some simple information that could be included:

- Information to order a lead soil testing kit from the EPA

- Lead paint testing strip

- Informational pamphlet including situations/locations you should look out for

- When your child should start getting tested for lead/ensuring your pediatrician tests for lead yearly

Additionally, knowing the historical context of your backyard, street, and neighborhood can help residents be more prepared to monitor their child’s BLL. This visualization below was created to help with such action; it allows the viewer to adjust the radius from the site of known contamination to understand the distance from the site to the viewer’s home.

I asked Rachel if she thought it was possible to ever “get the lead out” of Philadelphia, as their organization name states.

While she said it is most likely impossible to get the lead out, her answer argued that taking back your agency is completely possible. By having concrete, actionable steps to mitigate the risk, she believes that Philadelphia residents can take control of their children’s health narratives once again.