The History and Impacts of Big Pharma

Our society’s valuation of drugs, and the crucial role that drugs play in our daily lives, is manifested in the name “Big Pharma;” a critical analysis of history with an eye towards neoliberal policy enables us to see how the pharmaceutical industry gained this nickname.

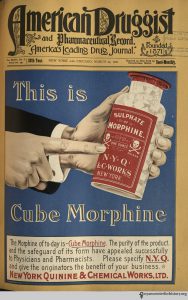

The Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914 marked the beginning of drug regulation in the United States. The government voted to instate these policies to control over-the-counter use of morphine, heroin, opium, or cocaine that were additives in common cold medications or those for toothaches (Kelvey 2018). These regulations were needed partially due to Friedrich Serturner’s isolation of morphine from opium in 1805, which triggered a market for pain killers delivered via tablet or hypodermic syringe (Kelvey 2018). However, at this time, drug producers only marketed their opioids and so-called “less addictive” versions to physicians. At the turn of the 20th century, physicians had been well warned through their social networks of the addiction present in their society and how this was fueled by specific medication ingredients (Kelvey 2018).

The concern of regulating addictive ingredients fueled the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, which marked the beginning of the Food and Drug Administration that we have today. From this point forward, pharmaceutical companies were not hindered but rather “coevolved” with the regulation to ensure that profits were maintained (Kelvey 2018).

Neoliberal influences, still acting in the late 1990s from Reagan-era deregulation, fueled the present-day opioid crisis by causing the 1997 FDA guidelines to allow pharmaceutical companies to utilize “direct-to-consumer marketing of drugs” (Kelvey 2018).

This act of “deregulation” did not deregulate the pharmaceutical industry for the benefit of the consumer to make their own informed drug choices (as neoliberalists will attest) but re-regulated the power of marketing to Big Pharma companies, such as Purdue Pharma.

In 1995, Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin; they marketed it as a “less-addictive” form of oxycodone because of its “time-releasing formulation…[which] allowed a single dose to last 12 hours” (Kelvey 2018). Suddenly, pharmaceutical companies hit the public with an onslaught of drug advertising (which “hit a peak of $3.3 billion in 2006”) while the companies specifically targeted physicians for opioid marketing (Kelvey 2018).

This video is an example of an advertisement which emphasized the non-addictive nature of the medication.

The commodification of health at the hands of the pharmaceutical industry took over. Purdue Pharma gave physicians “coupons” for their patients’ OxyContin prescriptions while funding over “20,000 educational programs designed to promote the use of opioids for chronic pain” (Kelvey 2018). In these health transactions, Purdue Pharma purchased not only physician’s loyalties to prescribe OxyContin, but healthcare education in general by ensuring that pain was viewed as “‘the fifth vital sign'” by physicians everywhere (qtd. In Kelvey 2018).

The take-over by Purdue Pharma in the 1990’s and the subsequent spike in OxyContin prescriptions shows the societal effects of the presence and impact of Big Pharma.

The company’s actions, coupled with the legislature that made their actions legal, led to a societal belief that health is transactional. This reinforced the neoliberal mindset that had enabled the drug epidemic. Additionally, the role of the “informed consumer,” a key component to a neoliberal market, provided a mechanism that enabled Purdue Pharma to hide their drug’s addictive effects. “Purdue Pharma knew that [OxyContin] was addictive, as it admitted in a 2007 lawsuit that resulted in a US$635 million fine for the company” (DeWeerdt 2019). Health behaviors by the population, such as “expect[ing] to receive a prescription when [one] go[es] to the doctor with a health concern,” have been cultivated by the pharmaceutical industry to drive profits by hiding behind the guise of patient “choice” (DeWeerdt 2019).

Farmer calls out how the pharmaceutical industry drives health inequality by describing his clinic’s actions in Haiti:

“Medicines are not sold at the Clinique Bon Sauveur, since selling medications means that those who cannot pay do not receive therapy at all: we are the provider of last resort. Instead, doctors, rather than a patient’s social standing, decide who needs what medications” (Farmer et al 2003, 167).

Farmer’s fight against diseases such as AIDS and tuberculosis display the inequities driven by the pharmaceutical industry. He does this by providing ethnographic evidence of how the industry’s drug prices inhibit vulnerable populations from accessing much-needed medications (Farmer et al. 2003).

The Power of Big Pharma Skews Our Perception about Health and Drugs

An additional aspect that we need to be critical of to expose structural violence’s workings is scientific advancement. More concisely, we need to dissolve our tendency to believe that there is a molecular basis for every health behavior that pharmaceutical companies can render with a pill or treatment. The belief in a neoliberal, unregulated market, which influenced the rise of Big Pharma and subsequently led to the belief that health is transactional, additionally skews our perception to the proximate and the molecular.

Society’s preoccupation with finding the proximate, or molecular, cause of disease rather than focusing on the distal causes, such as structural violence, render social forces more invisible.

We can readily see this phenomenon in the COVID19 pandemic in the United States, where media points consumer attention to the production, safety, and efficacy of a potential vaccine rather than investigating the connections between poverty and COVID19 positivity rates and developing impactful policy to counteract it.

We can readily see this phenomenon in the COVID19 pandemic in the United States, where media points consumer attention to the production, safety, and efficacy of a potential vaccine rather than investigating the connections between poverty and COVID19 positivity rates and developing impactful policy to counteract it.

For the opioid epidemic in the Riverwards, ad campaigns cite the drug buprenorphine or “bupe” that can be utilized as an opioid partial agonist to relieve withdrawal symptoms; this constitutes a form of opioid dependency treatment (Whelan 2019, Buprenorphine, n.d.).

In Summary

I am not arguing that proximate causes of disease and poor health are not important; rather, I think that anthropological methods can be utilized to communicate and affirm to the public that distal causes of poor health arguably matter more than the proximate ones. This is because as each day that passes, structures and relationships continue to perform violence on populations; this violence furthers already present inequalities, which only continue to grow as time passes. However, I believe that our focus on the neoliberal economy, where an individual can purchase their health insurance and acquire the medication they need when they need it, keeps these inequalities in place. Individuals who do not suffer from structural violence act as the ideal consumers in a neoliberal market, where they have readily access to pharmaceuticals because they either have the ability to pay for the insurance to cover the cost of the drug or have the means to pay out of pocket; these actions further fuel the pharmaceutical business to focus on creating so-called “lifestyle” drugs that cater to a privileged population, while disregarding many of the diseases and epidemics that plague those at the bottom.

Connections to Data Visualization

Data visualization has the power and potential to change how we understand things; visualizations that direct our focus to the molecular continually enable the neoliberalism mindset and drive pharmaceutical companies. These visualizations subsequently shift our attention away from the individual and the structurally violent acts that are factors in their current situation. If society were to see health in a more holistic sense, meaning as a product of the environment, history, access to care, and other relational factors, the drive to and the power of the pharmaceutical industry would decline. Ethnographic data visualization presents an opportunity to shift society’s perception, from the molecular to the distal.