MAMA SUNSHINE

Roz’s Story

Roz’s story is one that has been told many times; one can infer this from the number of local articles she is cited in online, in addition to the methodical way in which she tells it. Roz defines her story around violence, as she tells it by describing how her family members were taken from her by acts of violence.

https://whyy.org/segments/one-womans-mission-to-make-sure-everyone-carries-narcan-including-drug-dealers/

She begins her story at 16 years old, when her ex-boyfriend Donald Williams attempted to murder Roz and murders Roz’s boyfriend. Donald only served 15 years in prison, and was released without Roz’s knowledge. He then committed another murder, of a women named Maria Seranno. Roz testified at Seranno’s hearing, and was able to ensure that Williams would remain behind bars for the rest of his life, without the possibility of parole. She said that these series of events imbued her into anti-violence advocacy, although she was only 16 at the time. She wasn’t sure how to act, besides sharing her story with family, friends, and neighbors at such a young age.

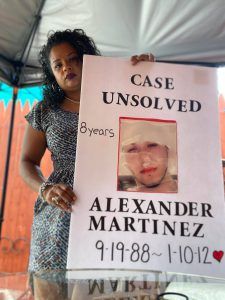

Gun violence continued to plague Roz’s life, as her twin sister Kathleen Pichardo died of a self-inflicted gun shot wound at age 21, and Roz’s baby brother Alex was murdered in 2012 at age 22. Roz’s step-father, who raised her since she was 6, embodied the result of this senseless violence and passed away one year following Alex’s murder.

A visualization of Roz’s life story can never fully depict the sadness, grief, and emotion it contains; however, the image of overlapping bars depicts a perpetual presence of violence. It also visualizes an abrupt end to Roz’s loved ones’ lives juxtaposed with an emergence of activism.

Despite the constant loom of violence and grief that has encompassed Roz’s life, she said that her story and what is to come in the future:

It doesn’t instill fear in me; I kind of feel like I’ve got to keep going.

Roz Makes Unsolved Murders Visible in Philadelphia

The urge to keep going and to make her siblings’ stories heard has made Roz a well known anti-gun violence activist in Philadelphia; her activism centers on uniting her community, as when an individual loses a loved one in a senseless act of violence, they feel alone in the world. However, Alex’s murder gave Roz insight into the systems of investigation that surround gun violence and specifically the vast number of unsolved murder cases in Philadelphia. She realized that she wasn’t alone in the pain and grief she felt, and that someone needed to “bring light” to the unsolved cases gone dark in Philadelphia.

Advocating for continued investigations into Alex’s death, and others like him, ensures to Roz that her brother is known in society and that his death, alongside others in Kensington, is not simply erased by the power of gun violence. “Erasure” of lives and of history is one mechanism in which structural violence acts, and Roz’s methodology of activism aims to directly counteract this (Farmer 2004). Roz fills countless fliers and posters with the faces and names of those who were murdered, and yells their names back into society. She draws outlines of bodies in chalk on the sidewalk, and places numerous body bags outside of spaces such as City Hall. All of her actions exist in the dichotomy of filling the space of absence; while individuals bodies are physically lifeless, Roz’s actions ensures that their spirit and legacy are alive. Her voice of resistance articulates that there should never a void in action driving towards the reassurance that knowledge of a closed investigation gives an individual.

Roz’s firsthand knowledge of the power of activism has connected her to other individuals in the Philadelphia community who have stories similar to hers; they are not necessarily united against one common individual, but the collective idea of violence that is enabled by society. This is represented through the signage workshops Roz holds, to ensure that their poster boards depicting the faces that represent unsolved murders are created with uniform formatting. In protest, they appear visually united.

Not only is her community united, but they are powerful numbers wise. Many of the images that Roz posts on her Facebook page, Operation Save Our City, depict the vast numbers represented by unsolved murders. But, rather than reduce these individuals to statistics and numbers on a graph, each individual’s face is visually represented. Roz is creating data visualizations in her own community, using her own community’s environment as a canvas.

A common thread form all of these examples is the collective power that emerges from sources and times of grief; below is a sound clip where Roz describes a specific instance where she could feel and see this power in her community.

Ethnographic Evidence of Embodiment

Roz’s story of the effects of embodiment on the body provides an ethnographic example for how studies of embodiment of structural violence are not defined solely by epigenetic, molecular evidence. Roz’s story of her stepfather does not include the minute detail of the epigenetic workings of grief on the body, but is symbolic of how structures that have created and enabled violence to exist in these communities can have broad reaching effects.

Roz described that the murder of a family member is nothing short of “overwhelming.” While Roz channeled her grief and energy into activism, her step-father’s days were defined by his loss. Roz articulated that while there was an absence of her brother, her father’s grief was perpetually visible:

“We would sit around the table and we can see the grief, we can see the mourning that never went away for him; He would always say, ‘You know, I want to go to sleep and not wake up.’ He would say these things constantly, and we would try to encourage him, you know, to move forward and to do something to channel this energy. And he didn’t. And ultimately, it took his life.”

She understands that embodiment is powerful, it has the ability to drastically affect health, and it needs to be mitigated in some way to ensure the lives of those she cares about. She described the acts of gun violence as a ripple effect, not only affecting the murdered individual but those in which the individual is relationally connected with:

What happens to one’s heart, what happens to one’s health, when you carry so much grief.

Her narrative of engagement with the Kensington community, which has jumped back and forth from gun activism to feeding the homeless, and eventually into harm reduction, represents how she is aware when one subject is wearing too much onto her body; rather than giving in, she switches focuses and diverts energy in a constructive manner.

Methodology to Counteract Embodiment of Violence

Not only is Roz advocating for peace in Philadelphia, she creates community circles centered on healing by talking about pain, how to mend it, how to fix it, and how to not constantly “swim” in it. For Roz, that means not allowing grief and sadness to take over her entire day; in the audio clip below, she shares some of the methods her and her mother use to acknowledge and act on their feelings while not allowing these feelings to define them or their days.

Operation Save Our City

Roz intersects, in an attempt to dismantle, many of the relationships that tie together and perpetuate structural violence through her multiple layers of activism; she advocates to society to change its standards, to the police force to continue investigations, to the community to band together against violence, and to the family members who have lost loved ones to violence to speak up. By acting both proximally and distally to structural violence, Roz is attempting to sever all of structural violence’s ties to her community.

Many of the organizations, activism events, and daily interactions Roz has with the residents of Kensington can be seen as a methodology to counteract the embodiment of violence; her organization, Operation Save Our City, and her involvement with Prevention Point Philadelphia are only two examples of this. They represent the promise and possibility of the Kensington community.

Annual Camp Out for Peace

One of the events that Roz’s organization sponsors every year is the annual Camp Out for Peace, which aims to bring together all the narratives of unsolved murders. Every year in January, which marks the month of her younger brother’s murder, Roz sleeps in a tent on a corner lot in Kensington for three consecutive nights. As she sleeps, she is surrounded by images and posters of the loved ones her actions are commemorating.

Many of the patterns in Roz’s activism, specifically the creation of posters with faces and speaking the names of those now gone, affirms that in our society, identity is tied to a living, breathing body. By recreating an individual’s presence in a community through repetitive images, Roz confronts this standard to attest that while an individual’s heart no longer beats, their identity and legacy is far from gone.