The Neighborhood Watchdogs

Let’s take a step back, into the past

150 years ago, in the Riverwards

The Consolidation Act of 1854 had been recently signed (within the past twenty years), formalizing the join of the Northern Liberties of Philadelphia to the city of Philadelphia. Most Philadelphia residents lived in close proximity to their work site, which contributed to the growing popularity of the row home; the row home was a solution to Philadelphia’s crowded geography and lack of transportation. Homes were simply built in “row style,” meaning narrow and tall in order to optimize the space available around the industry of the time.

The visualization below provides contextualization for how prominent the “row home” is in Philadelphia, in addition to displaying how the majority of homes in Philadelphia were built in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

While the city’s neighborhoods were structured so that everyone could walk to work, projects of expansion and connection between the Riverwards and Center City were underway. Technologies such as the city passenger car, steam engine, and railroad would rise and alter the dynamics of these small, isolated communities (“Philadelphia History: Chronology of Significant Events” n.d.). Modern day communities such as Kensington and Fishtown would no longer be isolated from Center City; rather, they would become centers of major production, fueling the city’s transformation into “the workshop of the world.” These communities were comprised of Polish, Irish, and German immigrants who found solitude on the outskirts of the city. They made a livelihood for their families through trade crafts or catching fish from the Delaware River. This is where the name Fishtown arose, as it marked the location of fisheries in the city of Philadelphia (Maule 2016).

Now, let’s fast forward 50 years into the 1920’s

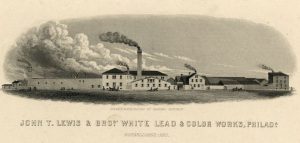

The mark of the 20th century introduced a rapid rise of industrialization in the Riverward communities. The government and large companies were key players in Philadelphia, and specifically the Riverwards. Companies such as the Stetson Hat company employed over 10,000 Kensington residents, as did Cramp’s shipbuilding company during times of war. Cramp shipbuilding was one of the premier shipbuilders in the United States and one of few that was able to successfully transition from wood to metal shipbuilding. This transition was due to its local workforce that was specially trained for niche tasks along with the relationships it had with nearby metal and engine companies (Farr et al 1991).

Metals were widely used in a variety of crafts and trades in the Riverwards; large volumes were needed in the geographic area and many metal smelting companies rose in Philadelphia to meet this need. At its peak, Cramp employed over 10,000 residents. However, after World War 1, Cramp lost a substantial amount of business due to the government’s agreement to “cut its output of warships in a ratio agreed upon by the Great Powers at the Washington Conference of 1921” (Farr et. al 1991). This, coupled with the effects of the Great Depression, shut down not only the manufacturing of Cramp ships but additionally its large, skilled workforce. When governmental need rose prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor in World War II, however, the government stepped in to relieve Cramp of its debt through governmental programs in order to expand the United States’ naval department (Farr et. al 1991). Once the United States received what it required out of the region (notably, 22 submarines produced between 1943-1944), the shipyard was sold and its workforce of 10,000 were yet again out of jobs (Farr et. al 1991).

And now today, in 2021

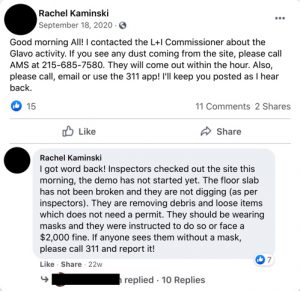

The communities that comprise the Riverwards have undergone drastic changes not only in composition, but also in their role. They are no longer seen as the workshop of the world, but as geographic areas that bear the legacies of historic contamination due to the metal smelting that occurred in the previous factories. In 2021, rather than walking to work in a factory, as residents in the early 1900s would have done, Rachel Kaminski wakes up worried about the health of her children. Rather than fishing or contributing to the assembly line at the Stetson factory, Rachel wipes the wheels of her stroller, vacuums, and avoids neighborhood streets where demolitions are occurring. Her daily routine, and daily worries, are a burden inflicted by decisions of the past.

Social Media Collaboration as a Method of Community Surveillance

Linda* (name altered for privacy) was kind enough to share with me the story of her childhood in the community of Kensington. While her story is primarily focused on witnessing the rise of the opioid epidemic, I asked her about her thoughts and opinions of environmental contamination. At the time of the interview, I had recently developed a visualization which showed me how widespread yet concentrated lead poisoning was in Philadelphia. I was shocked to find that many historical lead smelters were in her community of Kensington. When I asked her about this, she contrasted her descriptions of the visibility and immediacy of the opioid epidemic with the invisibility of lead pollution and poisoning; she stated,

People aren’t overly concerned about the possibility of that chemical plant emitting [referring to Anzon], because it’s been there forever. It’s not bothering anybody, what’s anyone to care?

After talking with Rachel about the problems surrounding accountability and education of lead poisoning in Philadelphia, Linda’s response did not surprise me. It reminded me of Rachel’s expression of frustration when she described to me how many Philadelphia council-people make sweeping generalizations that “their kids dealt with lead on a daily basis, and they became doctors and lawyers!” It all ties back to the “it doesn’t affect me, so I don’t need to worry” mentality that plagues our society.

Murphy (2017), alongside other anthropologists, argue that chemicals such as lead, do indeed bother people and, in fact, become part of our bodies. The unknowing infiltration of lead molecules into an individual’s body constitutes an invisible form of structural violence. As Murphy argues, inciting awareness of these dynamics and assisting individuals in how they can reconcile themselves as chemical and human beings is one proposed way to attempt to dismantle structural violence. Linda’s dialogue provides an example for how danger can exist in denying the relationship between lead, our environments, and our bodies; many of these dangers can be remedied through access to tools that promote lead education and awareness.

One such tool is the Facebook group Get the Lead OUT: Riverwards Philadelphia

Members of this online community feel very differently than Linda and are acting to decrease health inequalities in Philadelphia. Similar to other Rustbelt cities and geographic areas affected by environmental chemical poisoning, Facebook groups such as Get the Lead OUT (GTLO) have been created to unite residents concerned with ensuring that re-developers adhere to the responsibilities and legislation in place. These policies are in place to maintain standards of environmental and community protection. Online boards, such as this Facebook page, act as a point of contact for, “concerned neighbors and citizens focusing on the soil-based lead issue in the Riverwards section” where they are able to engage in conversations of, “education, support and safety” (Facebook).

These spaces serve as evidence of collaborative efforts that acknowledge the ties between violence and health. There is an added layer of urgency in this context, as the lead smelting history of Philadelphia is over-represented in the city’s youth. In these online communities, residents post images and locations of concern and other group members’ make efforts to contribute more information. Such information often includes historic images of what infrastructure used to occupy that same land. They additionally share advice as how to confront negligent contractors, who often refuse to obey clean air requirements. Both of these examples risk further toxic embodiment for these families. Many of these Facebook conversations pose questions surrounding the morality of contractors making profits at the expense of current community members’ health and lives, and what victims of lead poisoning can do besides keeping their houses “really really clean.”

Ethnographic Data Visualization Gives Insight into GTLO’s Fight

Rachel Kaminski is a key contributor on GTLO’s Facebook page, rallying online community members to voice their concerns in meetings with housing developers and sharing images of delinquent demolition and construction practices happening in Philadelphia. Rachel is a mother of two children and an advocate for lead-free communities. To read more about Rachel’s story, and how her activism is attempting to alter the city’s standard healthcare screening practices, click here.

The first step in understanding the importance of Rachel’s activism and the context of her story is to comprehend the vast amount of historical smelting and contamination sites in and around Philadelphia county. Philadelphia, and specifically its Riverwards, were once referred to as “the workshop of the world” because of the diverse manufacturing plants densely located along the riverside communities. Many of these historical workshops focused in textiles, such as the famous Stetson hat factory. Others such as Cramp’s shipyard on the bank of the Delaware River, united all forces in the shipbuilding process- from metal smelting, design, and actual construction. Because industry was so concentrated, many workshops produced products needed in the assembly of other goods; a common example of this was metal. Metal refineries, and specifically lead companies, used methods such as smelting to separate different types of metal for different products. Cramp used so much metal in building ships that they bought a metal-production company in order to streamline his assembly of metal-plated ships (Farr 1991).

Heavy utilization of metal resulted in a very high demand. This demand is reflected in the vast amount of smelting locations that were historically present in Philadelphia. The interactive contamination map below presents a unique viewpoint of this historical legacy, by juxtaposing the locations of present day Philadelphia with structures that once occupied the same geographic space. However, this visualization aims to begin to orient the viewer towards the aftermath of contamination that remained after these factories were demolished.

The data for this visualization was graciously provided by Professor Himpele and the Anthropology Department VizE Lab project “Visualizing Philadelphia.”

This visualization digitally recreates the geographic locations where old factories once stood. While it conveys a tone of absence, as these lead factories no longer exist, it does not have the capability, nor the data, to describe the historical absence of communication in Philadelphia communities. The structurally violent aspect of historical environmental contamination is that the majority of the Philadelphian population is unaware of the health risks inherent to their environment. The population is unaware that commonplace activities, such as nearby construction or their very own backyard, could devastatingly affect health. In the clip below, Rachel describes this dynamic; she never knew, before the Inquirer article’s release, that she should be testing her environment.