Socially Ingrained Violence

Describing Philadelphia

As a white girl growing up in a predominantly white, affluent suburb of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, I would have described Philadelphia as the location of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 because that was what I learned in school. Its narrative would have been defined by the stories of Ben Franklin’s famous experiments, the crack on the Liberty Bell, and George Washington crossing the Delaware River.

As a high schooler, I would have cited Philadelphia as the city my parents met; both were enrolled at Thomas Jefferson University.

As a sophomore at Princeton University, interning for the summer with Jefferson’s Health Design Lab, I would have described Philadelphia as a complicated city; I would say the aura changed by the “section.” I was renting an Airbnb apartment in Rittenhouse Square, which is characterized by posh, eclectic rowhomes, brick streets, and trees with “twinkle lights.” Rittenhouse had high-end department stores and was occupied by high-end shoppers who wore thick sunglasses and walked with intention.

This contrasted with the Kensington neighborhood, in which the lab collaborated with local organizations on programs involving public health outreach. We picked up needles on the irregular patches of grass before setting up lawn games while residents looked at us suspiciously. There was garbage everywhere on the street, and the sound of the El was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. However, Kensington residents were some of the kindest, most energetic individuals I have ever met in my entire life. They taught me to look past the physical landscape to the opportunity of what “could be.”

As a senior at Princeton University, writing my senior thesis about the relationships that envelope Philadelphia, I would describe the city as complex and in need of contextualization. I would describe the city as a hotspot for the COVID19 pandemic and a hotspot for public health innovation. I would say that the city is the center of the opioid epidemic but is also pioneering harm reduction in the United States while protesting how our society socially constructs “health.” I would say that the neighborhoods that constitute Philadelphia today result from a complex history of relationships: relationships of power that enabled the rise of some while inhibiting the rise of others.

Complexity

I have concluded that my chosen word is “complex” after hearing my interlocutors’ stories, contextualizing them, and layering them with data. While describing the relationships that intertwine their lives, their personal narratives also document the social forces that exist in Philadelphia. Their stories are clearly different, yet they significantly overlap when discussing the contexts of structural violence.

A pattern that I want to open for discussion throughout this ethnographic, digital account is that relationships and societal patterns established in the past are not limited to the past; they have actively shaped how our society functions and is organized today. Additionally, many of the narratives told of geographic spaces and populations focus on the narrative of the majority, which often does not make space for narratives of structural violence. As the introduction to structural violence section described more fully, structural violence exists not as an emerging property but as the result of accumulative conditions; additionally, viewing it as an emerging property enables violence to perpetuate.

Philly’s Nicknames as a Basis for Discussion

I will utilize some nicknames as examples to describe many of the dynamics often attributed to Philadelphia. Philadelphia is often referred to as “The City of Homes,” “The City of Brotherly Love,” and the “Workshop of the World.” These nicknames represent significantly simplified patterns; their language and implications do not include narratives of racism, invasive infrastructure, discrimination and lack of access in healthcare, environmental toxicity, and commodification. Here, I suggest that visualizing maps of violence throughout the history of Philadelphia will function as a particular mode of seeing, interpreting, and representing; it will attempt to counteract how those not afflicted by structural violence are often those who have the power to visualize in society, and whose perspective is often privileged in visualization.

The Workshop of the World

While Philadelphia is no longer considered a “workshop,” its legacy is still present through resident narratives, old infrastructure, and environmental toxicity. However, describing Philadelphia as previously the “Workshop of the World” begs the question of what is it now?

Philadelphia fueled its early economic growth through its locally-owned workshops ranging from metal works to textiles along the Delaware River; many of these started out as family businesses, where specialization in craft made some of the highest quality products in the United States. As Licht (2012) details, you cannot trace this legacy to a single factory or product (albeit Philadelphia was well regarded for its metal-works, shipbuilding, and textile industry); rather the legacy is the result of the aggregation of bodies working in synergy to build a name for their neighborhood while providing for their families.

Discussing the narrative of the workshop of the world in the framework of bodies rather than factories or companies reinforces how bodies are crucial aspects of infrastructure in a city; the “common” narrative of the “workshop of the world” oftentimes does not include this vital aspect. Specifically, when we talk about the disappearance of industry and manufacturing in areas such as shipbuilding and textile, it is not collapsing industry but many individuals’ perfected craft and source of income. It’s not simply the disappearance of industry- it’s the disappearance of individuals from the economic relationships of society.

This dynamic can be visualized- an example is illustrated below, which contrasts the number of individuals employed in the manufacturing industry in 1940 versus in 1980; while industry in Philadelphia was already declining in 1940 (although it did pick back up slightly in the 40’s due to World War II) there is still a visually stark disparity between the number of individuals employed in this sector in the period of 40 years.

While this data presents a slightly skewed image (it shows the percentage of persons employed in this sector per census tract, so some areas have smaller populations resulting in a “deeper red” color, mouse over some of the areas to see this pattern), it still depicts the disappearance of the manufacturing industry throughout the entire city of Philadelphia. While this industry employed most individuals in this area, the economy shifted; this shift caused unemployed, and residents sought employment in another industry.

This shift also affected movement patterns: jobs were no longer available in neighborhoods such as the Riverwards. These neighborhoods were constructed specifically to house families in close proximity to their worksite, creating a localized, community-driven center for daily movement. Now, individuals who reside in these neighborhoods have to go elsewhere for work.

The City of Homes

While society regards Philadelphia as the City of Homes, due to its large percentage of rowhomes and early home-ownership rates, this narrative obscures the discriminatory housing practices embedded in the United States’ housing policy. Between 1935 and 1940, which coincided with a period of growth for the African American population in Philadelphia, the federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) graded neighborhoods based on real estate data. These grades, reflected in color-coded sections of city maps, determined which residents and neighborhoods were deemed “safe” for housing investments (Nelson, n.d.). This graded system is one link in the relationships of structural violence that we see today, as some neighborhoods and sections of the city could prosper at the expense of others.

In the grading system for the HOLC, a “worthy” home or geographic area was semiotic of “worthy” or societally “valued” bodies. In determining a worthy home to invest in, the federal government and the city of Philadelphia determined which residents were worthy of investment; this reinforced the standard of white mobility while hindering the advancement of individuals classified as Jewish, Italian, or African American. In these studies, homes, neighborhoods, and residents were described as “stagnant,” “infiltration of the foreigner,” “of disagreeable odor,” “obsolescence,” “negro concentration,” and “not in good condition” (Nelson, n.d.).

The idea of the home functioned as infrastructure, organizing the movement of bodies within the geographic space of Philadelphia (Larkin 2013); in this way, “infrastructure” ensured that those with higher HOLC grades were able to improve their homes, move to “nicer” areas, or move out of the city altogether into the suburbs. At the same time, the home as infrastructure kept bodies deemed less by society in controlled areas, ensuring that they could not achieve the economic resources needed for home improvement or moving to a “nicer” area. These methods of control organized the idea of movement in society in two ways: it ensured that home values in lower graded areas would not trend upwards and that home values in “nicer” areas would not trend downwards because of “infiltration of the foreigner” (Nelson, n.d.).

Click on some of the geographic areas colored in the map below; the tooltip will reveal the “data” of the HOLC. It is important to note that this data, and the maps that the HOLC created from it, were produced with a specific intention. The HOLC determined which areas to produce data for, and which to omit; looking for the absence of data is just as important as the presence of data in analyzing structural violence. They are social creations, representing the world through the gaze of those who have the power to inflict violence on the population.

The City of Brotherly Love

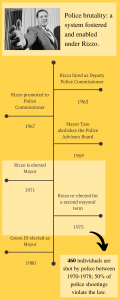

Like I’ve elaborated on earlier, many of the mainstream narratives told about the city of Philadelphia come from those who hold power; in the history of Philadelphia, that has been the white male. An analysis of the “City of Brotherly Love” nickname shows that many of the relationships of power ensure that brotherly love serves white males at the exclusion of others. This has historically acted to oppress Philadelphia’s black male population. The stories surrounding the structural violence enabled by the Philadelphia police department, especially under Commissioner and Mayor Frank Rizzo, exemplify this.

Mayor Frank Rizzo (1971-1980), previously Police Commissioner Rizzo (1963-1970), is a disputed figure in Philadelphia history; the fight over whether or not to remove his statue at city hall exemplifies this. Those who favored him believed that he was a “fair” enforcer of the law, while those opposed were personally affected by structurally violent relationships he enabled the police force to cultivate. Under Rizzo’s term as police commissioner, Philadelphia had socially constructed the black population as the origin of violence, unrest, and unruliness. The infrastructure of institutionalized racism was seen in the white population of Philadelphia, as they were nervous for their perceived “diminishing power” as more and more white families moved to the surrounding suburbs.

Under Rizzo’s years as Philadelphia’s Mayor, 469 individuals were shot by the police (data from 1970-1978). 128 of those occurred in 1974, one year before the beginning of Rizzo’s second mayoral term. A Public Interest Law Center Study found that fifty percent of these shootings violated United States law and that 75 of those individuals were unarmed and accused of non-violent crimes. The majority of these violent acts were against Philadelphia’s black population. There were no systems of accountability in place, as Mayor Tate (Mayor preceding Rizzo) had abolished the Police Advisory Board, which handles and investigates all citizen complaints against the police force.

(statistics credit to Russ, Dain Saint, Craig R. McCoy, Tommy Rowan, Valerie. “Black and Blue: 190 Years of Police Brutality against Black People in Philadelphia.” https://www.inquirer.com. Accessed February 28, 2021. https://www.inquirer.com/news/inq/philadelphia-police-brutality-history-frank-rizzo-20200710.html.)

These numbers, this data- the individuals whose lives are reduced to police statistics- overwhelmed me. I dug into data of the Philadelphia police department under different mayoral terms to analyze Rizzo’s term against other police chiefs. I found that it wasn’t necessarily the size of Rizzo’s police force that resulted in these statistics, nor was it the ratio of police officers to the Philadelphia resident population. In the visualization below, a larger circle indicates a larger ratio of uniformed police officers per 10,000 residents; a darker color indicates a larger police force.

Rather, the violent statistics recorded from Rizzo’s term were a result of the environment he cultivated and normalized, and the relationships that he reinforced; time and time again, Rizzo articulated both through words and actions that the African American population of Philadelphia needed to be handled and managed by the police. They did so violently, with inhumane actions, a lack of oversight, and no retribution. It was an established system that had been cultivated since the Consolidation Act of 1856 that enabled Rizzo’s actions and allowed him to build upon them.

One of the reasons cited for the Northern Liberties union with the city of Philadelphia in 1854 was increased religious-based violence (specifically, anti-Catholicism) in the Riverwards neighborhoods; because there was no official union between the city and its surrounding Liberties, there was no infrastructure to mitigate violence and foster peace between differing religious groups. The Consolidation Act called for 1 policeman per 150 residents in the territory union. This consolidation event established the beginning of violent methods of control to be utilized on the Philadelphia population.

As I discussed more fully in my section detailing Roz’s story, embodiment of grief and mourning for one’s loved one, especially at the hands of gun violence, has drastic health effects in the community. By creating systems that enabled this violence, Rizzo is one of many actors responsible for inequalities in health in the Philadelphia population.