Place Matters

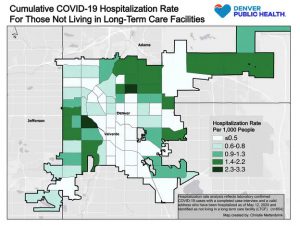

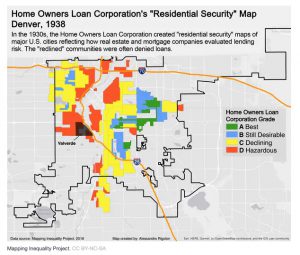

Since March of 2020, data visualizations showing the proportions of cases and deaths by state and county started to fill my media screens. These maps highlighted differences that were “emerging,” which indirectly indicated that they were not previously there. Many visualizations, such as the examples below, took these visualized differences and added layers of context, citing how inequitable structures, such as environmental contamination, access to healthy food, or healthcare access, could inform county by county differences in COVID19 cases.

https://theconversation.com/is-your-neighborhood-raising-your-coronavirus-risk-redlining-decades-ago-set-communities-up-for-greater-danger-138256

https://theconversation.com/is-your-neighborhood-raising-your-coronavirus-risk-redlining-decades-ago-set-communities-up-for-greater-danger-138256

In this sense, the COVID19 pandemic has revitalized the idea that “place matters” in individual and population-level health.

However, I began to wonder why this idea of “place matters” only received broad-scale attention and social acknowledgment when the health obstacle, COVID19, is impacting the entire population of the United States and the world.

Why do health problems, such as the heroin and opioid epidemic, not get this same contextualization and social acknowledgment of place’s significance?

These questions affirmed that, even amid a pandemic, my research questions were relevant; they are arguably even more relevant than they were in the past. Kensington, Philadelphia has been portrayed in the media in articles such as this example as the United State’s opioid epidemic’s geographic center for many years.

However, unlike Nemeth & Rowan’s COVID19 article, no context is added to the maps and images produced from drug activity in this area; the opioid epidemic is portrayed as a geographically localized phenomenon, where criminalization measures have historically been utilized as a mechanism of control. Many projects, such as Jeffrey Stockbridge’s Kensington Blues portraiture blog, aim to humanize Kensington residents by sharing their personal experiences and narratives, showing that they are interwoven with the obstacles of drug abuse.

However, many of these re-humanization projects are limited. They do not connect Kensington’s present-day narratives to the historical structures and processes that cause individuals to be located in a specific geographic place and therefore experience the effects of “place matters” on health.

In light of the COVID19 pandemic, I am questioning why the idea of “place matters” is relevant now and not beforehand in the emergence of the opioid epidemic? Is it because the one epidemic affects us all while the other is seen as geographically isolated, “brought on” by a specific population, and lastly is seen as “not our problem” in a broad scale, societal sense?