Infrastructure Shapes Relationships

In defining structural violence as an aggregate of violent relationships, it is imperative to assert that relationships in our world do not only exist between humans. They are also present, albeit still invisible, between humans and their social creations. Because of this complexity, visualizing structural violence’s impact on health necessitates an analysis into the history and landscape of Philadelphia to look for “overlooked” networks of relationships. To visualize the typically invisible relationships of structural violence, it is necessary to consider the “extraneous” actors or seemingly innocent social creations in our everyday lives. One such extraneous actor is infrastructure.

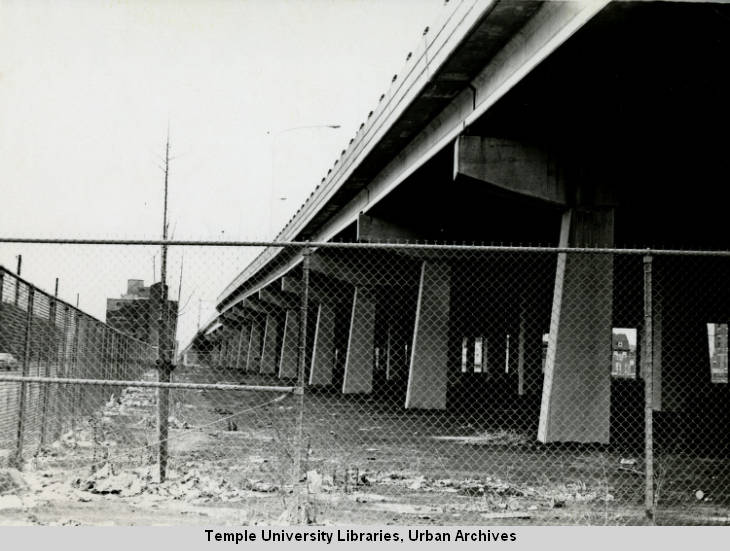

An anthropology of infrastructure raises questions such as, what is the influence of the built environment (such as highways, subways, and elevated rail lines) on health in Philadelphia? These questions are essential to consider because infrastructure, specifically where it is placed, can offer insights into other domains in our society (Larkin 2013). An anthropological perspective of infrastructure argues that physical forms such as Philadelphia’s I-95 highway/Delaware expressway, in addition to the city’s multiple above and below ground transit routes, “shape the nature of a network” (Larkin 2013). Infrastructure is not a passive actor but was intentionally created, designed, and placed by humans; because of these relationships, infrastructure inherently carries the power to benefit some over others.

Ethnographic data visualization can be a beneficial methodology to discuss how Philadelphia’s infrastructure is symbolic of structural violence and how it reinforces the relationships of power that constitute structural violence. This section will investigate where infrastructure is placed in Philadelphia, why they were created, who they serve, and conflicts of power they represent.

From the Delaware River to a “River of Concrete”

(Blas 2010 citing Homer Bigar, 130).

As I discuss in sections such as “The Vacuum Effect” and “The Neighborhood Watchdogs,” many private companies in the Riverwards influenced the type, shape, and design of community infrastructure through a necessity to organize movement. At the time, community form needed to meet function. Factories in Philadelphia were primarily concentrated in the Riverwards neighborhoods because of the land and natural resources they required; this was usually supplied by the means of the Delaware River and the riverbed. The specific locational needs of these factories meant that all of their employees had to be housed in the same, small community as the factory. Communities in the Riverwards were able to grow through Philadelphia’s iconic row home architecture, which consisted of a narrow design and multiple floors up. It enabled families to live within walking distance to their job site. The Delaware River, in a way, functioned as natural infrastructure, shaping the organization of communities and enabling their markets.

By the 1960’s, the Delaware River was abruptly replaced by the I-95 highway; it snaked along the riverbed, mimicking the River’s curves and bends. Not only did it mimic the River’s shape, but it assumed the River’s name: the Delaware Expressway.

All of these factors, in summation, are symbolic of the valuation society placed on the Riverward communities in Philadelphia. Namely, visualizing the narrative of Philadelphia’s I-95 highway allows us to connect the absence of a local narrative (the market and jobs that the Riverwards historically contained) to the presence of a national narrative. This narrative is structurally violent, as it forever altered the Riverwards landscape by severing it with the landscape that enabled its historical rise.

Powerful Presence of a National Narrative

The National Interstate and Defense Highways Act of 1956, put into effect by President Eisenhower, fundamentally altered the relationships of movement and space in the United States. Before his presidential terms, Eisenhower was the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe; during his time in Europe, he observed the societal differences between the United States and Germany, specifically their relationship to movement enabled by the German autobahn (Blas 2010, 128). Eisenhower’s military identity followed him into his presidency and greatly influenced his view on policy. With the rise of McCarthyism and the Red Scare, the culture at the time in the United States instilled an atmosphere of fear and anxiety in the American people (Blas 2010). Therefore, political agendas and new legislation, which aimed to increase the United States’ security, were generally well-received.

Fueled by the emotion at the time, Eisenhower’s government’s top priority was filling the perceived holes in our national defense; meanwhile, local communities held different priorities. For communities such as the Riverwards, the deindustrialization that followed World War II fundamentally altered the market. With the demand of their goods absent, many of the factories that the Riverwards residents relied on for employment (and other community amenities) shut down. These communities were in a vulnerable position and did not have a voice; the national narrative of the United States, which partially consisted of the Highways Act, overpowered these residents’ local needs in favor of “the greater picture.” In the end, governmental power enabled the Philadelphia local government to take advantage of the downtrodden Riverwards communities and their land to fulfill the US’s “need” of a national highway system.

As Stewart (2011) states in her thesis “The Construction of Interstate-95: A Failure to Preserve a City’s History”, tensions following World War II (and specifically the beginning of the Cold War) influenced the creation of a national highway system. Suddenly, the government valued less dense communities because they were “safer” in the event of an enemy attack (Blas 2010). The devastating effects that atomic bombs could cause in a major urban metropolis (known firsthand by the United States, in dropping bombs on Japan) only increased this anxiety. This caused a rapid push for highways, influencing individuals to move to the suburbs rather than reside within the city limits.

Highway design, specifically its location, functioned to benefit the individuals in which it would serve; highways functioned to allow the white, wealthy upper class to reside in the suburbs outside of the city while enabling ease of mobility back into the city for work or recreation. In contrast, the residents of neighborhoods where the government placed the highway did not, and many still do not, own automobiles because of their household income. This dynamic is represented in City Planning Commission Executive Director Edmund Bacon’s comment (Gottlieb 2015):

We think it better not to fight with the automobile…but rather to treat it as an honored guest and cater to its needs.

At this time, the “needs” of the United States were additionally the “needs” of the upper-class, leaving the working-class residents of Philadelphia’s Riverwards to deal with the long-lasting effects of such needs.

The local and national governments of the United States saw communities such as the Riverwards as disposable; the construction of the I-95 highway was not the first example of this relationship.

A significant span of the I-95 highway was constructed along the city’s eastern edge, right beside the Delaware River. This same stretch of land, specifically Beach Street, enabled the Riverwards to rise in the late 19th century and early 20th century; it was the location of many factories, the Pennsylvania and Reading Railroad Company, and the hub of the shipbuilding industry.

The United States government had already articulated a few years prior that these communities were only of use when they functioned to meet the needs of the “collective good.” One example of this is how the government re-evaluated the Cramp shipbuilding company’s debts that had caused it to go out of business in 1927 (Farr et al., 1991). It opened the company’s doors again in 1940 to meet the increased demand for warships that World War II had necessitated (Farr et al., 1991). Between 1941 and 1945, the company produced 45 vessels for the US Navy (Farr et al., 1991). After the end of the war, when the government no longer required a constant flow of ships, they shut the company down again. The 10,000+ residents that contributed to the wartime effort were forgotten. As the United States celebrated the win of democracy, the skilled labor and industry present in the Riverwards plummeted.

By constructing a national highway that effectively cut off these neighborhoods from their historical and emotional energy source, society symbolically declared that there would be no future market possible in the Riverwards. The considerable cement barriers that now tore through the Riverwards neighborhoods presented a physical representation of the new “modern life” that drastically contrasted with the culture that the Riverward factories had cultivated. The highway physically altered society’s movement around the Riverwards, which symbolized that the world had shifted away from the niche goods in which the Riverwards specialized in.

Additionally, the creation of the highway system in the United States, and its placement in the Riverwards, reaffirmed that some social networks mattered more; in this instance, the narrative of the United States need for security mattered more than the individual families and communities that would be impacted by invasive infrastructure. The emergence of the highway in the Philadelphia neighborhoods shifted the power allocation from private companies to the city government; up until this point in history, private companies had primarily controlled the communities’ history, narrative, and culture.

We can find a visual representation of these dynamics in historical maps of the structures, homes, and companies ameliorated by highway construction. These images show how the highway tore through the center of Cramp’s shipyard, the Philadelphia and Reading railroad company, endless homes, and even a school.

The absence of industry in the Riverwards which “rationalized” the highway’s placement was only further compounded with the highway’s presence. Specifically, infrastructure enabling mass transit also directly impacted the industry present in the Riverwards. As automobiles and the roads they required became more affordable, accessible, and safe, the prevalence of the iconic Stetson Hat decreased in society; the hats were too large to be worn inside an automobile (Krulwich 2012). This coincided with the Stetson Hat factory’s demise. Additionally, the highway and automobile rendered the railroad obsolete, which decreased the foothold the Reading and Pennsylvania Railroad company had in Philadelphia.

Toxic Highways, Figuratively and Literally

Not only was I-95 geographically placed in communities now rendered “obsolete” by modern advances, but the city of Philadelphia also happened to place the highway system on severely toxic grounds.

As I discuss in Can We Get the Lead Out?, the industrial past of the Riverwards communities caused vast environmental contamination with lead. Rachel, a childhood lead poisoning activist, told me how her Facebook activism group formed out of a collective need to monitor local demolitions and housing renovations, which stir up lead in the soil. Without proper protocols, this lead dust produced can poison the community.

However, major demolitions and environmental disturbances that re-introduce buried lead into the air do not just occur in homes. They also include city-wide projects, such as highway construction and eventual repairs. We can see this in the I-95 highway: I-95 was nowhere near perfect to begin with; not even 40 years after its completion, a multi-billion project of repairs began. With this context in mind, the infrastructure of the highway is organizing movement away from locations in the Riverwards. Community members have to avoid the areas of construction (which generates lead dust) in order to protect their health.

Ethnographic data visualization of infrastructure can help visualize these overlapping geographies; however, this data cannot visualize how community members’ health was affected by the highway’s emergence. It can simply indicate health effects by extrapolation, with our knowledge of the effects lead has on the human body. The visualization below layers data symbolic of different time periods: the contamination sites represent Philadelphia’s early industrial history, the line of I-95 marks where the city of Philadelphia constructed the system beginning in the 1970s, and the pink boxes indicate sites of significant highway repairs that are currently occurring in Philadelphia.

Continued Highway Maintenance Projects

Not only were the Riverwards and the communities of NE Philadelphia subject to invasive infrastructure, they are also currently subject to another round of massive, I-95 renovation projects. According to the 95Revive website, this current construction consists of redesigning ramps, constructing new bridges, addressing “design deficiencies,” “improve access to important expanding economic nodes,” and “fit I-95 into its urban context.”

The image below depicts the areas of current and future construction.

Continual maintenance of a highway system, especially novel additions and design, has the risk of reintroducing lead dust back into the Riverwards environment. Rachel discussed with me how the highway construction is affecting residents’ lives and health:

I’ve seen now with the construction of I 95, there’s a lot of dust and a lot of debris that comes from that, and they don’t do any cleanup; they throw up a bunch of tarps on some existing fences. They don’t mist anything down; they just say like, all right, this is good enough. And meanwhile, people are coming back and their cars are covered in God knows what.

Additionally, highway reconstruction is affecting the resources that Philadelphia residents have safe access to; many sites of recreation and children’s playgrounds which have tested positive for unsafe levels of lead are located in close proximity to highway construction sites. Rachel has inferred that the city’s reason for not currently remediating the sites, and instead opting to “close” them, is because of the environmental contamination that is inherent in the highway construction process.

Relationships Constructing the Highway

Relationships of structural violence influenced where the I-95 highway was located geographically and what form it took. In the Riverwards’ neighborhoods, many row homes were obliterated to make way for the above-ground, cement barriers that would constitute the roadway. This screen recording of Google Maps below shows the unsightly nature of the highway, and also how it cuts off residents from the Delaware River. For many individuals, living in rowhomes on the edge of the Riverward communities, the highway physically became their backyard.

The opposite occurred in the Society Hill neighborhood, which was an “up and coming” wealthy neighborhood; Society Hill is cited as one of the first instances of gentrification to occur in Philadelphia in the 1960s. Edmund Bacon, who served as Executive Director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission from 1949 to 1970 (the commission pushing for the highway’s materialization), lived in Society Hill (Gottlieb 2015, Ammon et al.). Society Hill residents had occupations associated with social capital, such as lawyers; when they heard of the highway design, they launched a tirade against the planning commission to seek an alternative solution for the highway in their area of town (Ammon et al.). While other communities fought to have a similar solution, none of their requests were granted. So, rather than having a rectified highway providing unsightly views and an inconvenience of access to the river, Society Hill’s portion of the highway was designed to be “below grade” and feature a “capped” section.

This screen recording of Google Maps below shows the travel path of I-95 through Society Hill and the “tunnels” or “caps” designed to form parks, access to the river, and hide the highway from residents’ sight.

Furthermore, this image taken from Google maps shows the “cap” from an aerial viewpoint. It contrasts greatly to the second image, depicting the highway in Northeast Philadelphia.

The construction of I-95 is an example of how the form, and geographic placement, of infrastructure not only organizes networks as Larkin (2013) argued, but is symbolic of the relationships which constitute structural violence. Relationships that are associated with power, such as those requiring graduate school education, were and still are associated with specific geographic locations in Philadelphia. The communities of the Riverwards had few job prospects and were undervalued by society, while Society Hill residents ensured that other architecture firms were able to contribute novel ideas to the highway plan (Ammon et. al).