Dear Paris Reporters — Thanks for your rich impressions of Paris day one.

Florent will put edited versions of the blogs under your doors. I did not grade them — that will come shortly.

You’re on a roll. Keep it up! Bonne nuit. ES

Dear Paris Reporters — Thanks for your rich impressions of Paris day one.

Florent will put edited versions of the blogs under your doors. I did not grade them — that will come shortly.

You’re on a roll. Keep it up! Bonne nuit. ES

Sacré-Cœur at night

Photo by Anhar Karim

The Sacré-Cœur church in Paris is a majestic and awe-inspiring structure towering high into the sky. It is topped off with two statues of horsemen in full armor, raising their swords as if ready for battle. And on this night, Hamdi stood right in front of the church at Montmartre square, armed with only some light up toys and trinkets. And yet, he could not feel more at home.

Montmartre wears the Parisian night well. Here visitors, Parisian and tourist alike, happily saunter through the space, drinking beers and pulling in strangers for a leisurely dance or two. Some teenagers sing a rowdy song to the left and to the right a young couple stares out at the Parisian skyline. Here Hamdi stands with a small sack full of trinkets: Eiffel tower toys, light up keychains, some tacky hats— things one would buy to remember the moment, to latch a happy memory onto an object in order to recall that happiness again and again. But Hamdi does not need these trinkets he sells to his customers. The fact of his life in Paris is enough fuel to sustain his smile.

The festively lit square right beside the church

Photo by Anhar Karim

Hamdi is not his real name. He requested that his identity be kept a secret because he is not legally in France.

“I’m just trying to do business and send money back to my family,” he says, waving his one free hand energetically to summon customers his way. He says that he knew from a young age he liked doing business and that he was good at it. And so when the time came to go earn money for his family, he decided to put his skills to use. It’s the mind of a businessman that brought him to Paris. He comes to this spot of town many nights of the week, or to several other similar spots, and sells whatever he can to people. He admits that some see it as in poor taste to take advantage of tourists’ naiveté by selling them overpriced trinkets, but he insists that this doesn’t make him a bad person. There are the bad undocumented immigrants in the city who rob and injure. But he’s not doing anything like they are. He’s only trying to make an honest living so he can make some money for his family at home.

“If you go to Gare Nord, you’ll think that you’ve found Bangladesh here,” he says. The area just outside the Gare Nord train station is a portal to South Asia. The place is sprinkled with Indians, Pakistanis, and, yes, Bengalis. One need only walk into one of the many Bengali restaurants there, eat the traditional pani puri snack, and he may forget that Paris exists outside the doors.

The view from Montmartre square

Photo by Anhar Karim

But not everyone wants France to look like this. Hamdi talks about how the country now has its own Donald Trump candidate now under the name Marine Le Pen. And, Hamdi laments, it looks like she has a chance at winning the coming first round of the presidential election. He notes that she only has support because there is a lot of racism in the country. Many people, like Le Pen, cannot even look upon darker faces. “Racists,” as he calls them, wonder where he came from and wish that he would leave. Though, interestingly, Hamdi says that it’s not only the native French that bear this guilt. Arabs, though likely victims of discrimination themselves, will often discriminate against Bengalis and other dark skinned people they meet.

Despite all of these unsettling factors, Hamdi does not see Paris as an unwelcoming home. People have never outright asked him to go away or to go back to his country. No one has ever so directly called him out like that in the three years he’s lived here. He knows those negative sentiments hide under people’s surfaces, but he sees hope in the fact that people choose to conceal them. When asked if he sees himself as a French Bengali, he responds,

“I am living in France, and I am Bengali.” Hamdi has not found that the French identity is his, but nevertheless he can proudly say that he loves the new home he’s made of this city.

By: Katie Petersen

Professor Elaine Sciolino seems to know everyone on the rue des Martyrs, and she has to say hello to them all.

La rue des Martyrs is Sciolino’s home turf and the subject of her 2016 book The Only Street in Paris. It also happens to be historically rich, authentically quaint, and increasingly gentrified at once.

As she leads the group of Princeton students, intensely jet-lagged but propped up by café au lait, Sciolino stops in to say bonjour to virtually every shop-owner.

That’s the rule, she explains. “Stop in for a chat even if you’re not buying; never, ever be rude,” she prescribes in The Only Street. Naturally, “this means I cannot be rushed. It can take thirty minutes to walk a few hundred feet.”

Or more than half an hour, if you’re not only catching up with a friend but also introducing a group of students to Paris. Sciolino takes the time to share with the owner of a produce stand that one of her protégés is writing about tomatoes in Paris. Without hesitation, the man grabs a knife and selects a small, lumpy, red and green tomato from a pile. He carves pieces for the whole group to try that are so sweet they taste like candy.

The tour makes another stop in a small Italian market, where a printout of Sciolino’s book cover hangs prominently as one of the shop’s claims to fame. “This is my favorite place on the rue de Martyrs, because it’s a little bit of Italy in Paris,” says Sciolino, who hails from Buffalo, lives in Paris, and is of Sicilian origin.

The owner is – no surprise – delighted to see her. “You see how it’s different than Princeton?” Sciolino asks, turning to the students. “You come in, they know your name, you say bonjour. This is the spirit that I want you to take back to Princeton…so that you come in here and you feel at home.”

That is the spirit that the street is fighting to retain. A law dictates that small shops like these that close down can only be replaced by other artisanal businesses.

That’s not to say that new businesses don’t pop up. Some, like the carefully curated olive oil shop Première Pression Provence, are more recent additions and feature a steeper price tag. “This is an example of the new artisanal rue de Martyrs,” the owner says. “There’s a lot of little shops specialized in one thing, and a trend of people looking for something real, something special.”

If they’re looking for things real and special, the only street in Paris is a good place to start.

By: Miriam Friedman

Paris is an artistic world trapped in a small city. In movies and books the city seems limitless; but in truth, the French capital has an area of only 33.5 miles. Most of the famous sights—like the Eiffel tower and the Louvre—are concentrated in the city center, making it possible to see many of them in a single day. But there is so much more to the city than crossing sights off a checklist. To truly see Paris, the tourist must linger, noticing the medley of people—both foreigners and locals—who make this historic metropolis the center that it is today.

Paris is a city of art. In the Marais area, in the fourth arrondissement, there are temporary sidewalk murals on the concrete beside rows of old brick archways. An exchange of smiles ensues as someone tosses a coin in the bowl before the drawing, and continues onward. Only a short walk away at Pont Neuf, an iron fence is overrun with colorful love-locks. A couple stands at the center writing their initials on the lock. Glancing left and right, the two toss the key into the river, kissing each other as they leave.

Beyond the conventional art, eating in Paris is also an experience. The French value presentation just as much as they do taste, and they decorate each dish with colorful swirls and garnishes. Even a common croissant is a culinary delicacy. Deconstructing these pieces, then, takes time. Therefore, meals are eaten leisurely—usually taking around two or three hours—which means that people have the chance to have long and relaxed conversations. While indulging in this elaborate French cuisine, acquaintances become friends.

A visit to Paris is incomplete without a stop at the Louvre. But the museum is filled with more than famous paintings and their visitors. Artists who acquire a permit can come to copy the works of their idols like Monet and da Vinci. The spectators do not know the hard work that goes into obtaining permission to paint here, but take pictures beside these modern works anyway.

In a hallway on the second floor of the museum, lies Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. But almost as interesting as the painting itself is the crowd of people gathered before it. Selfie-sticks are banned from the location as they interfere with the photos of too many visitors. This doesn’t stop most from finding a way to capture a photo of themselves with the lady’s famous smile. Somehow, the thousands of tourists who take the same picture manage to add their own creative spin—be it a silly face or gesture—that makes their “art” unique.

Outside the museum, the Parisian aesthetic of cobblestone streets and gothic buildings makes walking the roads magical by itself. It is possible to wander in Paris for days, weeks, months, even years, and not see everything. Each street has deep roots, a rich history, and an exciting possibility for new adventure. Still, somehow only one day in Paris can have a person head over heels, falling for a city she once knew nothing about.

But it is impossible not to fall in love. Paris fulfills every fantasy, and more. Though it is small, it is also endless.

By Katherine Trout

The main course for a dinner at Miroir.

The main course for a dinner at Miroir.

PARIS, FRANCE – It’s 9:15pm and Paris is hungry – and many locals are craving their native French fare. For those near the Rue des Martyrs in the 18th arrondissement, Miroir, one of the last authentic French bistros, is the place to be on such an evening. The seats have been filled at Miroir since before 9:00pm, but that doesn’t stop a line of twelve from cluttering at the door. Despite the intimidating queue, passersby pause at the storefront to scan the menu taped to the glass door. Several pairs are won over and join the waiting party.

Customers are greeted with the friendly bonsoirs of Chef Sébastian Guenard and his small crew – and by the intoxicating smells of wine and sweet broths. The restaurant name Miroir, French for mirror, is fitting. Several large mirrors with gold painted frames don the walls. A red leather booth lines the perimeter of the left wall; small, mismatched tables stand opposite of it. Many of them have been pushed together, morphing them into a makeshift banquet table for larger parties. Looking to the right, a wall of French wines stands. Slipped in between several bottles is a hardbound copy of The Only Street in Paris, a book by Elaine Sciolino of the New York Times. The book features Guenard and his bistro on several occasions.

Tonight’s menu is an array of classic French cuisines. Slices of baguette and salami are laid out on wooden platters. They are shortly followed by cheesy puff pastries and fried seafood bites. Foie gras, a French delicacy, is brought out as a starter dish. What appears to be thin slices of savory butter adorned by slices of red beets and chopped green onions is none other than cuts of a force-fed duck’s liver. The main course, an impeccably cooked chicken with homemade broth and spices, is a crowd pleaser. The dessert, quenelle chocolat, closes the meal – it is a rich, thick mousse, drizzled with caramel and chocolate crumbs.

The restaurant, from its menu to its décor – is unmistakably French. But these intricate French concoctions aren’t created by native Parisians. Rather, they are the creations of Guenard and his three immigrant cooks in a tight six-by-six kitchen.

A tall, dark-skinned cook towers over a burning stove top, stirring and moving around metal pots holding different broths: chicken, mushroom, beef, seafood, pork, and cauliflower. His name is Lassana, and he is an immigrant from Senegal. He speaks little English on top of his French, but he tries to communicate with English-speaking diners through his fellow cook, Muhammad. After all, restaurant patrons are eager to learn the secrets of his culinary creations. Muhammad, an immigrant from Sri Lanka came to Paris to find work two years ago – and has been a cook at Miroir ever since. It’s the first day on the job for the third cook, Franky, another immigrant from Sri Lanka. Together, they give customers a taste of Paris.

Chef Sébastian Guenard and his cooks are breathing new life into the French bistro.

Today, the class made its way down the Rue de Martyrs, the site and subject of Prof. Sciolino’s latest book. But before we reached the lively and historical street, we ate buttery croissants around the corner from our luxurious hotel and across the street from a billboard. The billboard promotes François Asselineau, presidential candidate for the political party he founded, the Popular Republican Union (UPR). “Participate in history,” the billboard demands. “Frexit = Protection of Our Industry.” As we sipped café au lait at a small Parisian boulangerie, the billboard reminded us of the tense political climate in France right now. Asselineau’s proposal to remove France from the EU shows that the charm we find in traditional Paris for many conservative French is something to be protected from outsiders. Along with the sweet charm of historical Paris comes xenophobia and harmful French exceptionalism.

A man in a black hoodie walked by the billboard. The back of his sweatshirt bore a familiar mark: the word “Bai” imprinted in white, with the outline of a small leaf dotting the ‘i’. Bai water is a flavored drink infused with antioxidants. Creators of the drink use the overlooked coffee fruit – the berry that surrounds the coffee bean – to make a drink that is sweet, rich in Vitamin C, and available in flavors that range from Costa Rica Clementine to Ipanema Pomegranate. The company was founded just eight years ago in Princeton, NJ. As a Princeton native, I watched with excitement as the drink spread from the shelves of the local natural foods grocery store to Whole Foods locations in Manhattan. A person in a Bai sweatshirt walking on the Paris streets is testament both to the Princeton company’s quick success and the power of a global economy.

On the Rue des Martyrs, we entered a number of small shops. Each specialized in a single product or family of products: cheese, pasta, fruit, seafood, rotisserie, pastries, books. The exceptional quality of the products showed the power of craft specialization. One person asked, “Why don’t we just do this in the U.S.? It’s clear that this is so much better.” As it turns out, the government has designated this street as artisanal. This means that any time that a shop goes out of business, another artisan business must take its place. The charming arrangement of single-product shops does not just come about naturally. Rather, governmental design and regulation maintains this traditional commercial stretch.

As we entered a newer store specializing in olive oil, Maison Bremond 1830, it became clear that modern aesthetics had invaded the artisanal business model. While some patisseries and poissonneries looked like they came right out of a 1950s photograph, this shop had a modern design. The business owners had developed a brand easy to promote—one of earthy colors, wooden textures, and sans serif typeface. A few storefronts down, a pastry shop sells madeleines, the small, traditional French cake. The pastries are as old and French as the country itself, yet there are only fifteen or so visible through the display case, laid out equidistant from each other. The menu is short, the options displayed in an unassuming black font against a vibrant pastel background. A pair of tourists occupies one of the four tables; the rest are empty.

Though many older artisan shops thrive, these newer stores mark a change. The quaint charm of a fishmonger weighing the scallops for tonight’s dinner may not always be enough. These new shops infuse the traditional business model with modern business principles of branding and minimalist design.

Le Bouquinaire, a bookshop with an over thirty year tenure on the rue de Martyrs, seems out of a storybook: bodies constantly pop through the door, letting in a warm wind that fills the narrow stacks of a cozy kingdom surveyed by the old, tautly-faced owner perched on his stool in the corner. Guy Bertin, 71, plays the character of the quietly-sour bookseller; his temperament seems part of the Parisian bookshop’s setting. Behind Bertin’s mood, though, is a real frustration at the shape of independent bookstore culture, and a real fear for the future of his shop, which make the picture seem a little more drained of color.

Independent bookstores are struggling to keep their doors open, and Bertin’s long tenure on the rue de Martyrs does not grant him immunity from booksellers’ communal fear. Although landlords have primes granted by the government that make rent more affordable, expenses are rising, and sales are dipping.

“It is not possible that this can remain as a bookshop,” Bertin says in response to Le Bouquinaire’s future after he sells it. He says that in the last year alone, fifteen bookshops in Paris have closed, leaving only three survivors. “All you need to do is walk around Paris to see the change.”

During his time on the rue de Martyrs, Bertin has watched the world change. He ascribes the dip in readership to the Internet, an impending threat facing independent bookshops across Paris. “Before, maybe 100 people wouldn’t have a TV or the Internet,” he says. “Now, maybe 10 don’t have them.”

Bertin offers one solution: if city hall designates his and other bookshops for cultural uses—to not just fix the price of rent, but reduce or eradicate it entirely—as it has for other spaces around the city, his business might be able to survive. Bertin is clear about the urgency of the situation: this is “the only way to stop the hemorrhage,” he says. His sour disposition makes a bit more sense when his goal is no longer to thrive, but perhaps just to survive.

BY LAVINIA LIANG

The sky was gray and it was starting to rain when a group of students from Princeton arrived on the Rue de Martyrs with their professor. Still, every shop owner greeted the group with warmth. The professor leading the Princeton excursion was Elaine Sciolino, former New York Times Bureau Chief in Paris.

Sciolino’s book The Only Street in Paris: Life of the Rue de Martyrs (W. W. Norton, 2015), holds true to the description of its subtitle. The book is a personal and narrative but also often journalistic account of everyday activities on the Rue de Martyrs. Many shops on the eponymous street and in the surrounding area carried posters of Sciolino’s book.

Sciolino’s students were pleasantly surprised by how well their professor knew the shop owners on the Rue de Martyrs, and how friendly the residents of the neighborhood were. Many of the shop owners provided food samples to the class, and still others tried speaking English with the students.

While eating at the bistro Miroir later that night with several Columbia University exchange students, the Princeton students were struck by how clean Chef Sébastien Guénard’s plating was. The chef served a delicious main plate of chicken over lentils, but the presentation of the dish, too, was tantalizing. “Presentation is everything,” said one unnamed student from Columbia University who is studying abroad in Paris for the semester. The Columbia University student went on to describe French customs that supported this statement. “They are very polite,” he said. “You must always say hello, always say thank you, always say good-bye.”

Florent Masse, a professor of French theater at Princeton University who also came along on the trip, expressed how “proud” he was of the Princeton students for dressing the way they did for walking around the Rue de Martyrs neighborhood. He said that they all had “very good looks,” and reemphasized that the way someone dresses is “very important in France.”

Dress also depends on occasion and location. One dresses down to go to the Sunday market in the suburbs; one dresses up to tour the Château of Versailles and meet its president. First impressions can mean a lot in a city that has painted its landmark monument, the Eiffel Tower, two different colors to ensure consistency when viewing. “It’s like makeup,” Sciolino had said.

By Mariachiara Ficarelli

The Japanese teahouse Toraya, found on a side street close to Place de La Concorde, is not cheap. You do not need to look at the prices on the menu to know this. The way the shop displays its sweets makes it obvious enough.

Wagashi, traditional Japanese sweets created with a sticky rice base, are placed in displays in the floor-to-ceiling windows of the storefront. They are molded into flowers and come in a palette of baby colors. Each one of these tiny, edible delights is placed on its own ceramic plate. The plate matches the color of the sweet it carries to the exact shade.

The sweets rival the lavish presentation of tartes aux fruits frais and bonbons found in the window exhibits of Sebastien Gaudard’s Patisserie des Martyrs. The wagashi are so sumptuous in their design that they could find a home alongside the jeweled accessories in Paris’s high-end designer boutiques.

While a delight to the eyes, the treats are not a delight to the wallet. A single sweet costs €5.50. Nevertheless, Toraya has found its niche market. The “bobos”- bourgeoisie bohemians- of Paris inhabit the sleek, wood paneled interior. Embracing a chic cosmopolitan lifestyle, these young, and upper class Parisians flock to teahouses such as Toraya.

Yet, the French embrace of Japanese culture is not new or exclusive to the “bobos”. The Japanese presence in Paris extends far beyond hip teahouses. Since the early 17th century, France and Japan have been engaged in a strong cultural trade. Monet, Degas, and Gauguin took inspiration from Japanese art, creating a new art style: Japonisme.

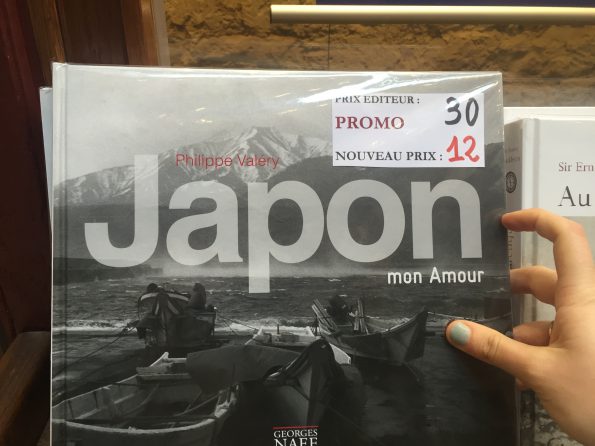

This century old Japanese presence pervades the city of Paris. A photography book on Japan lies hidden in a stack of books sold by one of the Bouquinistes along the banks of the Seine. Kimonos hang on a rack in the Kilo Shop, a thrift store in Saint-Germain.

There is no need to break a thrifty, university student budget at Toraya in order to find a piece of Japan in Paris.

A second hand photography book on Japan. Photo by Mariachiara Ficarelli.

A second hand photography book on Japan. Photo by Mariachiara Ficarelli.

By Iris Samuels

On a mid-March Friday evening, United Airlines Flight 57 was stocked with college students heading to their spring breaks in the City of Light. In the first few minutes, the head of the cabin crew announced that the flight would have ten “international” flight attendants. “We have one French-speaking flight attendant,” he added. “For your convenience.”

Only one? Granted, the United flight passengers heading to Paris were mostly American, but the French are known to be intensely proud of their language. Many of them refuse to speak in English, despite it being a mandatory subject in French schools. The disappearance of French from the in-flight experience is a precursor for what tourists can expect in Paris itself – a blurring of the fierce French pride that once characterized the city.

On rue des Martyrs, French pride is of the essence. While Americans have grown accustomed to massive supermarkets that sell everything from avocados to underwear, this street still maintains traditional small shops. Parisians buy their cheeses, breads and vegetables separately, taking pride in getting the best products from vendors they often know by name.

However, the French way is giving way to an increasingly global market. On one Saturday morning, a rue des Martyrs greengrocer was intensely proud of his produce, but admitted that the best tomatoes come from Sicily. The salespeople at the fromageries and boulangeries insisted that their stock was the best, but offered traditionally Italian, not French, products as proof. Japanese and Chinese fusion restaurants abound, marrying French cuisine with foreign influences.

In an archway leading from the Cour Carrée to the Cour Napoléon at the Musée du Louvre, a violinist and cellist played for passersby. According to Brice Le Clair, the Paris Conservatoire trained violinist, loyalty to France is no longer a top priority. He would far rather play for an orchestra in another European country, where the taxes are lower. He bought his violin from a maker in Cuneo, Italy, instead of in the Paris ateliers just a few blocks away, because prices were cheaper and quality was higher.

Parisians are still hesitant about speaking any language other than their native tongue, but being French no longer means turning your nose up at anything foreign.

When an American expat walked into Première Pression, a shop on rue des Martyrs selling olive oil from Province, he noticed a group of American college students congregating for an explanation on the shop from its owner. “Oh!” he exclaimed, “Refugees from Trumpistan!”

Paris, like many cities across the world, seems to be contending with the global tension between nationalism and globalism. On this cloudy day in the City of Light, globalism won the battle.