A collection of nine photos from nine (mostly) rainy days in Paris.

By Mariachiara Ficarelli

Paris in the rain is not enjoyable, at least for the tourist. There is nothing romantic about walking around the city in wellington boots and an umbrella. Your feet get cold and sore. You lose the umbrella halfway through the day. It lies forgotten in a puddle in a corner of one of the thousands of boutiques you ducked into, trying to escape the drizzle. So you buy a tacky umbrella with tiny Eiffel towers plastered all over it. It is not your first choice, but it is cheap and the only one you can find in your immediate surroundings. In case it was not already glaringly obvious that you are a tourist, now it is.

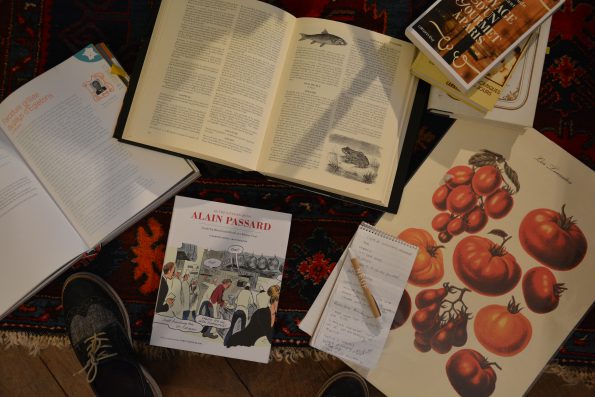

But, Paris in the rain has a charm. It allows for hours spent exploring the catacombs of churches; for long dinners, sitting nestled in between the warmth radiated by stacks of books and patterned rugs. It creates sighs of wonder, when the sun emerges for a brief second at sunset and illuminates the towers of Notre Dame. The rain offers an excuse to take an Uber across the city, the car-ride spent observing, through the foggy window, the blur of the famous lights of Paris. It is an excuse to pull up the neck of your black overcoat and walk with a purpose pretending to be a local (until you realize you are lost and then have to spend the next five minutes cowering under the covering of a storefront trying to find your way back).

Paris in the rain is for inventing. For the writer, the thinker and the explorer. Paris in the rain is not for the tourist.

© All Photos by Mariachiara Ficarelli

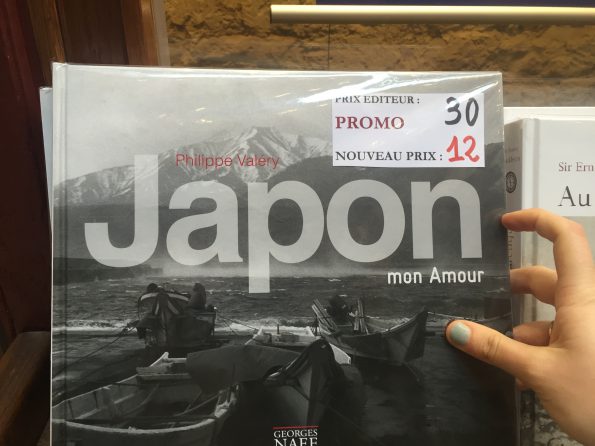

A second hand photography book on Japan. Photo by Mariachiara Ficarelli.

A second hand photography book on Japan. Photo by Mariachiara Ficarelli.