By: Miriam Friedman

It’s easy to fall in love with the external beauty of Paris, but it’s much more difficult to feel like you belong within it. For an ex-pat, the European customs seem strangely unfamiliar—the double-cheeked kisses, and late dinners a new and, at first, uneasy adjustment. But once these conventions become routine, it is hard to imagine life without them. In due time, both body and soul normalize to this behavior. What remains is a beautifully impure amalgam: an American disguised as a Frenchwoman.

As I leave in the morning, the first feeling of welcome does not come from speaking French. “Bonjour,” “Merci,” and “Au Revoir” are enough to communicate on a basic level, and smiles and hand gestures fill in the gaps for locals who don’t speak more English than I do French. Yet somehow, in the space between these comedic gesticulations, I have gotten to know some of the locals on the city streets. Seeing them is my symbol of “good morning.” Walking from the same Metro station every day, the familiar smiles transform into chitchat, and a kinship is born.

After learning the fundamental pleasantries, becoming French is accompanied by an awareness of the surroundings. The man in the fruit shop on the corner knows me by name, and already guesses which item I will reach for when I enter his store: the bright green apples. I’ve found the perfect place to purchase a warm croissant, and the type of coffee that goes best with it (espresso, of course.) I no longer let the baker surprise me with his choice of pastry; I’ve tried so many that I know which is my personal favorite.

Though the city stretches for only nine miles from east to west, it is easy to get lost. The endless alleys make it difficult to find my way without a map. Though I know now that locating the Seine means finding the trail that can lead me home, I do not choose to go there just yet. Wandering forward, I pass bridges, performers, vendors, and landmarks like the Church of Notre Dame and the Eiffel Tower.

I don’t look at my watch, and I don’t monitor how long I stand before each of them. I love the smell of butter and chocolate that radiates through the air, and the cool breeze that blows my hair in more directions than I can count. I take in the moment. The absurdity of placing so many wonderful properties along a single path only makes me smile.

With no fixed destination in mind, I take yet another step forward. I find myself walking through the arches toward the Louvre. I stand at a distance and watch as the tourist throngs take the same picture pinching the museum’s pyramid tip. I feel no need to do the same, and instead enjoy observing the people gather as I hear them speaking more languages than I can discern. Like me, these people came from across the globe to see Paris in all its glory. I continue onward as I wonder what secrets they have found, and hope that I will continue to find more of my own.

Despite its perception as cliché, the best part about Paris is still the Eiffel tower at night. As I lay down on the lawn before it, my body sinks into the bed of grass. Somehow, lying beside the monument makes my fears and worries disappear into the ether. I realize that Paris is no longer a forlorn dream; it is my reality.

On my walk back to the ninth arrondissement, I pass my greengrocer on the street. “La Bise” is the greeting that seems most appropriate. We exchange “Bonsoirs” and go our separate ways. It is 7 p.m., but my body no longer hungers for dinner; it knows the meal is not coming until later.

I have come a long way since my first step off the plane into the city of light. Though today, my body has left Paris, I’m not sure that Paris will ever leave me.

By: Miriam Friedman

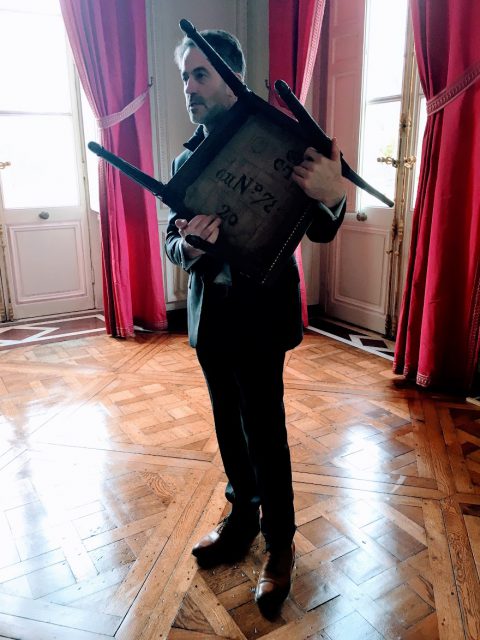

Not all chairs are meant for sitting. In the Petit Trianon, Marie Antoinette’s private estate within Versailles, the chair is the key to discovering some of the chateau’s deepest secrets. Though this piece of furniture exits in nearly every room of a home, its significance is often overlooked; but each piece has a story to tell—one which is not always as simple as it may first appear.

The Petit Trianon was originally built by Louis XV at the request of his mistress, Madame de Pompidou. Because it took several years to construct, it was the king’s next mistress, Madame du Barry, who first inhabited it. Years later, when Louis XVI was crowned, he gave the outpost to his beloved wife, Marie Antoinette, who took elaborate care in redesigning her new home. Though she only came here for fifteen days at a time, this location was dearer to her than her official place in the main palace.

Today, in a museum where a “do not touch” sign is a fixture at the entrance of every doorway, it is difficult for most visitors to discover the guarded mysteries of this historic chateau. Stepping against the red-roped barricade evokes a high-pitched squeak, indicative of an obstacle that has long kept people away from these secrets. But with the help of the chief curator, Bertrand Rondot, these enigmas are beginning to unravel.

At the chateau, chairs are a central adornment in almost every room. Nevertheless, only a small number of them were used traditionally as seats. Many of them have intricate carvings on their base meant for spectators to see. What, then, was their purpose?

Many of these chairs were carved to simulate a position of status and power. Looking closely, it is possible to see that some of the chairs have an insignia of the monarch. When Marie Antoinette took control of this location, she ordered that these chairs be reworked to bear her own symbol, “M.A.” While furniture is usually registered in files with a specific traceable number, Marie Antoinette destroyed her private “garde-meuble,” or storage locker, where these records were kept to prevent the palace headquarters from finding out how much she spent on this elaborate commission.

Of course, some chairs were indeed made for utilitarian purposes. Though much of the furniture on display was brought from other chateaux of the period, some of the pieces are originals. Many of the embroidered cushions are likely to have been sat on by Marie Antoinette and her visitors. But these too carry a secret. Though it is difficult to notice, all the cushioned chairs have covers, ones which only the curator can handle. Pulling back these layers of protection reveals intricate handmade embroidery that is now seldom exposed to protect it from light.

During the French revolution, the furnishings within the home were removed or destroyed. When officials chose to restore the home, they found many of these pieces. The chairs were one of the largest moving pieces that helped historians discern the nature of each room. With the help of Mr. Rondot, it is possible to see that the bottom of the chairs is marked with letters and numbers. For example, one displays “C.T. N#78, 20” which means Chateau Trianon, room seventy-eight, one of twenty pieces of this model made. By looking at the clues on these chairs, experts have been able to reconstruct the layout of the home.

Each chair has unique relevance, and tells the story of the room it occupies. Chairs change the posture of the actors, and can portray them as weak and insecure, or powerful and confident. By commissioning the chairs that she did, Marie Antoinette was making a point about the tone of each room. From displaying power, to imbuing the room with a unique atmosphere, the over 50 different types of chairs play a significant role in recreating the grand masterpiece of this private chateau.

Marie Antoinette’s chairs tell the unspoken tale of her private residence in Versailles. They are written about in few history books, but they play an integral role in understanding the life of a prominent queen, and the settings that she worked meticulously to construct. They are the forgotten secrets that escape the dialogue of a well-remembered palace.

By: Miriam Friedman

Catherine Pégard is a strong leader who has taken an unconventional path. Whereas most French officials steadily move through the system until they reach a position of authority, Pégard has managed to do something completely different. From journalist, to political advisor, and now, to president of the Palace of Versailles, this pioneer has changed occupations throughout her journey. But more than her professional success, it is her open-minded approach which makes Pégard a leader to admire.

From the start, Pégard was ambitious and determined. In 1982 at age 28, she moved from her birthplace in Le Havre to Paris to follow her journalistic aspirations. After thirteen years at Le Point Magazine, she was promoted to editor, and continued in that position until 2007. During her time at Le Point, Pégard met the young and motivated Nicolas Sarkozy—then only a young French politician—with whom she developed a close friendship. The two had great respect for one another, and when Sarkozy was elected President, he asked Pégard to join his team as an advisor. She agreed, knowing that this likely meant leaving journalism forever.

Immediately, Pegard’s mentality changed. She closed herself off from the press network she spent decades developing, and refused nearly every request for an interview. “An advisor is nothing and everything,” she said in an interview with Princeton students on Thursday, March 23. In this shift, she moved from the outside of politics as her own boss, to the inside of government as a public servant. At the Élysée Palace, she was a link to the people in a different way, but in one that she still considered vital.

Today, Pégard has a title of her own. As president of Versailles, Madame La Presidente is finally herself in charge of a vast array of people and departments. Over 1,000 employees of Versailles report to her; she makes the effort to meet everyone from the tens of security members in the palace, to the nine “fountaineers” who fix the fountains on the garden grounds. Though she can choose to involve herself in a purely administrative role, this is not her personality. She insists on personally insuring that the palace is pristine for the 7.5 annual visitors

As a woman, Pégard has surpassed still more challenges. She worked hard to rise to the top at a time when females where not considered equals. She admitted that today, it is much easier to be a woman in power. “The most important things have been done,” she says. Thanks to her success, others can look to follow this unorthodox trajectory.

To the French, Pégard’s path is bizarre. “Here, when you are a journalist, you stay one,” she says. But though her transitions have been atypical, Pégard believes her roles have not been mutually exclusive. She maintains that the qualities of “curiosity and innovation” that she learned as a journalist have forced her to look at situations more critically.

Now at age 63, Pégard feels as lucky as ever in her “sub-life.” Even at Versailles, she looks at her job as “always doing something different.” Like in her other positions, she admits that when she arrived at Versailles it was foreign to her, but that now she knows it well. “Versailles is more than just a museum,” she says. “It lives in the twenty-first century as it did before. But there is still so much to learn.” With this mindset, Pégard hopes that she will stay here for years to come, learning and growing with the history of her new home.

By: Miriam Friedman

The essence of Paris does not lie on the city streets; it exists below ground. From the diverse aesthetic of the different stops, to the etiquette of the people who pass through them, the Paris Metro is the often-overlooked mechanism that captures the city’s spirit. With its 131 miles of tracks, and its 297 stations, the Metro is a parallel, underground city, one that is as deeply embedded in the French psyche as it is in the limestone of Paris itself.

This year, the Paris Metro celebrates its 117th birthday, making it one of the longest running subway systems in the world. This enduring existence is deeply tied to the functionality of the city. The extended network of routes enables the Metro to cover 600,000 miles each day, a distance equivalent to circulating the earth ten times. According to R.A.T.P, the local transit authority, over seven billion people use the lines every year.

But more than the hard facts, the walls of the various subway stops model a wide variety of Parisian atmospheres. Ranging from broken concrete, to clean white tiles, and finally, to sparklingly painted tunnels, each destination has its own style. “I travel on line 1 from Champs-Élysées to Neuilly, and I see the glitter transform into ugliness. Even just the terminals remind me of different aspects of Paris,” says 22-year-old interior design student Lauren Asseroff.

Still, stark contrast lurks beyond the mere décor of the subway caverns. Between the travelers on the cars and the performers on the platforms, there is a wide range of conventions and behaviors. Unlike the subway in other major cities like New York and Hong Kong, commuters of the Paris Metro ride in silence. The only noise comes from the occasional tourist unfamiliar with this code, or from the whispers of locals with urgent gossip. “I always do the same thing, when I use this line: stand in the corner and read my book,” says 21-year-old architecture student Lisa Goutan —and she is not the only one. People on the Metro cars sit and stand as they read their books, or plug in their headphones, seemingly unfazed by the others that surround them.

Yet outside the car’s sliding doors, a very different reality awaits. There are accordion players, guitarists, and singers. Here is where the Metro bleeds its character. Marvin Parks, 41, is an American-born jazz singer, now living in Paris, who obtained a permit from the Musicians of the Metro Program to perform on the subway. Parks says that he has received support from both the city and the locals. “Besides the money in my hat, every day I am greeted with a smile, handshake, hug, well wishes, and inquiries about when my next show is,” he says. Though on most days, many Metro cars are quiet, entertainers like Parks bring personality to a system whose interior is all too serious.

The Metro is the heart of Paris. Not only is it the core method of transportation for most locals, but it also captures fundamental aspects of the French etiquette and culture. Without seeing the way that this body functions, it is difficult to generate a complete understanding of the city. Though the streets of Paris are beautiful and important, the underground level tells a much more compelling story about life in this center. The character of the Metro parallels the lives of the people who ride it; from young to old, a ride on the Metro means experiencing an old side of Paris with a whole new perspective.

By: Miriam Friedman

Coat hangers, beehives, and people punching trees, are strange fixtures to find in a garden; but the Luxembourg Gardens are in no way ordinary. These three spectacles are just some of the few interesting things within the park. But walking quickly or jogging on the gravel paths, one can easily miss these sights. To see beyond the rocks and trees, one must become an idle French stroller, a flâneur: calm, and lax, but attentive to even the finest details.

To an American, seeing two long coat racks and tens of hangers in a park, is an anomaly; but for the French, this is commonplace. These amenities are a resource to the tens of men who come to play the game pétanque in the center of the park. This game is a twist on American bowling, and it is one of the top ten most popular sports in France.

Most of the competitors in the gardens are men in their seventies, who spend their afternoons participating in tournaments for mild fame and a few euros. “It’s my favorite thing about retirement,” says retired doctor Yves Vichey, 73. Vichey says that the players warm up quickly. Coats usually come off within the first few tosses, and the coat racks provide the easiest fix. “The existence of the racks is almost as important as the balls in the game. Without them it would be hard to play,” he says.

Of course, pétanque is just the beginning of the magic of the gardens. Just past these courts, one young man punches a tree with thick gloves, while another fills garbage bags with sand. From afar, it is difficult to notice that on the tree there is a punching bag, and that the man in the sandpit is filling the bags to anchor his gym equipment. From afar, these people seem odd, but approaching them brings their actions into perspective.

On the far-right corner of the gardens lies another strange sight: a pile of little brown boxes on a patch of gravel. These are beehives which once housed and raised hundreds of bees. But stacked on top of each other, these wooden squares no longer contain bees, and the sign in front of them does not explain why. Asking the gardeners will reveal that the decreasing number of bees in Paris has temporarily exiled them from this home to find refuge in a safer place, sending them elsewhere to seek refuge.

So, what is the secret to finding surprises in the Luxembourg gardens? Discovering answers takes more than attention to detail: it requires initiative, asking the right questions, and pressing further when the answer does not suffice. By keeping both eyes open then, it is suddenly not only the coat hangers that begin to make sense.

By: Miriam Friedman

Stepping off the penultimate subway stop on Metro line 13 means entering a different world from the traditional picturesque Paris. This is Seine-Saint-Denis, a suburb of Paris, colloquially referred to as “the 93.” This is a place that tourists do not usually frequent, a place where the smell of garbage permeates through the air instead of that of buttered croissants. It is a place unlike the central area near the Eiffel tower, one where people dress in tattered t-shirts and sneakers instead of dresses and heels.

Seine-Saint-Denis has long been a unique suburb. But although people of various nationalities and religions have been living in the area for years, it has only recently begun to take pride in its diversity. The juxtaposition of shops that cater to different religious sects, and the emergence of exhibits that promote inclusion are a testament to the new self-worth of the district. Saint-Denis is attempting to recreate its image in a way that preserves its history, while embracing its modern heterogeneous culture.

To a first-time visitor, the outside Saint-Denis seems like a place wrought with contradiction. Clothing stores across the neighborhood sell a mixture of modest and conservative garments; merchants display short red party dresses and long black skirts beside each other for an equal fare of three Euros. While some people in the market dress in mini-skirts and short sleeve shirts, others cover their bodies with burkas.

But the inside of the suburb’s central Basilica, the Basilica of Saint Denis, is homogenous. Though its welcome book is filled with long messages written in both neat calligraphy and carelessly messy script, all the notes have one thing in common: they are all written in French.

In recent years, the Basilica has seen a decline in international tourism. One of the church guards, Amandine Deochampo, 26, insists that this is because of “terrorism.” Many of the terror plots have been hatched in this area. She says that with the rise in violent attacks, tourists are more reluctant to go to “non-essential” sites with reputations for being unsafe. Suddenly the 1,700-year history of the Basilica is forgotten, replaced by excursions to local cafes in the center of Paris. This is something the Church is trying to change.

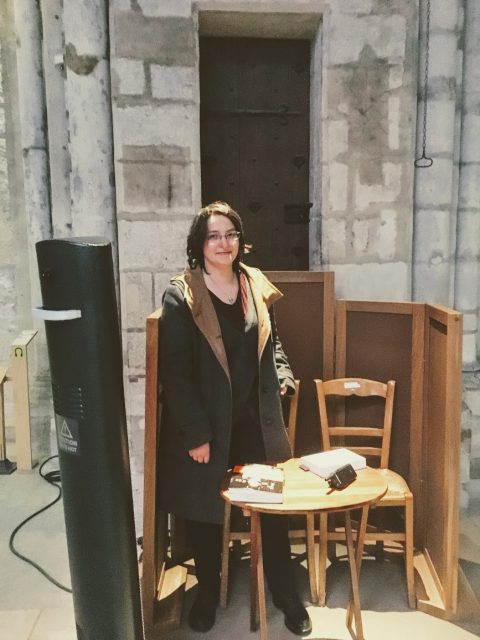

The “Mater” exhibit in the basement of the basilica stands at the height of this ideal. According to the 26-year-old museum manager Eliot Boulate, it was put on display “to promote the diversity within Saint Denis.” The mothers are faces of different women who live in the district. In the description on a panel in front of these portraits, the artist, Ariles de Tizi, explains this is a payment to “women and martyrs of exile,” a tribute to the fringe members of society; it is a welcome to the previously excluded personalities.

Since Boulate began working at the museum eighteen months ago, the Mater exhibit is the second one that has come to tell this tale of inclusivity. Last year, the church had a collection of religious robes made of fabrics from countries across the globe. The piece was well received, which prompted the board of the basilica to sponsor more long term projects of this kind. There are plans for another two similar exhibitions to come to the church caverns in the next year.

Today, the Basilica has informational brochures in six languages, and many signs throughout the building are translated into the most common four (French, English, Spanish, German). Aside from these translations, the cathedral is also creating incentives for more people to visit. It offers free guided tours to people with low incomes, and discounted tours to international students during the summertime. It also has more security than it did in the past. The staff hopes that this will elevate the dirtied status of the city, and encourage more people to visit.

These efforts show a Saint-Denis that is struggling to reinvent itself. But despite these attempts, the suburb is still wrought with high unemployment, drug crimes, and terrorism. Though it is cultivating a new identity, it still has a long road ahead.

By: Miriam Friedman

Paris is an artistic world trapped in a small city. In movies and books the city seems limitless; but in truth, the French capital has an area of only 33.5 miles. Most of the famous sights—like the Eiffel tower and the Louvre—are concentrated in the city center, making it possible to see many of them in a single day. But there is so much more to the city than crossing sights off a checklist. To truly see Paris, the tourist must linger, noticing the medley of people—both foreigners and locals—who make this historic metropolis the center that it is today.

Paris is a city of art. In the Marais area, in the fourth arrondissement, there are temporary sidewalk murals on the concrete beside rows of old brick archways. An exchange of smiles ensues as someone tosses a coin in the bowl before the drawing, and continues onward. Only a short walk away at Pont Neuf, an iron fence is overrun with colorful love-locks. A couple stands at the center writing their initials on the lock. Glancing left and right, the two toss the key into the river, kissing each other as they leave.

Beyond the conventional art, eating in Paris is also an experience. The French value presentation just as much as they do taste, and they decorate each dish with colorful swirls and garnishes. Even a common croissant is a culinary delicacy. Deconstructing these pieces, then, takes time. Therefore, meals are eaten leisurely—usually taking around two or three hours—which means that people have the chance to have long and relaxed conversations. While indulging in this elaborate French cuisine, acquaintances become friends.

A visit to Paris is incomplete without a stop at the Louvre. But the museum is filled with more than famous paintings and their visitors. Artists who acquire a permit can come to copy the works of their idols like Monet and da Vinci. The spectators do not know the hard work that goes into obtaining permission to paint here, but take pictures beside these modern works anyway.

In a hallway on the second floor of the museum, lies Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. But almost as interesting as the painting itself is the crowd of people gathered before it. Selfie-sticks are banned from the location as they interfere with the photos of too many visitors. This doesn’t stop most from finding a way to capture a photo of themselves with the lady’s famous smile. Somehow, the thousands of tourists who take the same picture manage to add their own creative spin—be it a silly face or gesture—that makes their “art” unique.

Outside the museum, the Parisian aesthetic of cobblestone streets and gothic buildings makes walking the roads magical by itself. It is possible to wander in Paris for days, weeks, months, even years, and not see everything. Each street has deep roots, a rich history, and an exciting possibility for new adventure. Still, somehow only one day in Paris can have a person head over heels, falling for a city she once knew nothing about.

But it is impossible not to fall in love. Paris fulfills every fantasy, and more. Though it is small, it is also endless.