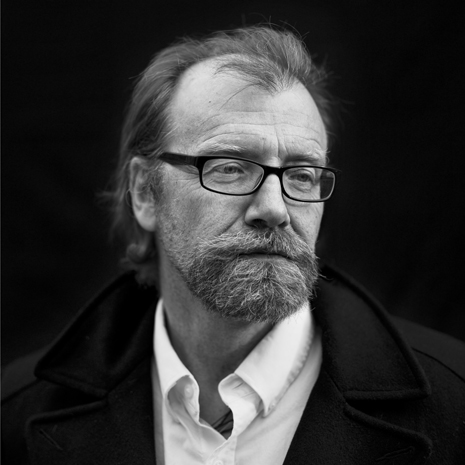

When American author George Saunders gave a reading at famed Paris bookstore Shakespeare and Company on March 20th, he could have been reading at any large American city. Most of the people who came to listen to Saunders read from his new historical novel Lincoln in the Bardo were young and English-speaking. They drank Kombucha and wore clothes that defied the unofficial French uniform; instead of monochrome layers, Oxfords, and a chic scarf, guests wore mom jeans and bleached out hair, sported bright lipstick and blunt bangs and colorful sneakers.

As soon as Saunders opened the floor to audience questions, however, the atmosphere shifted. Audience members began to ask Saunders about his thoughts on politics, democracy, and Donald Trump, and there is the sense that sense that many of the guests came to be calmed.

Elizabeth Howard, from Rochester NY and living in Paris for the year, brought her friend Rita O’Connell to Shakespeare and Company because she loves the store and wants O’Connell to see it, but also because of the “political issues of late,” Howard explained.

To Rita O’Connell, part of the draw was hearing Saunders’ savvy about United States politics, something that felt comforting to her. O’Connell made the pilgrimage for reassurance, and for community.

Shakespeare and Company has been a place of community for Anglophone literary expats since 1919, when Sylvia Beach moved from Princeton to Paris and opened a bookstore on the Rue de l’Odéon. The shop served as a meeting space for many of the literary greats of the Lost Generation, until it closed during the Nazi occupation of Paris when Sylvia Beach was arrested and interned.

The shop never re-opened, but in 1952 American bookseller (and New Jersey native) George Whitman changed the name of his bookstore–Le Mistral–to Shakespeare and Company. George Whitman ran the shop like a socialist paradise, offering a free room to anyone who tumbled into his shop in exchange for a one-page autobiography and some hours of work in the store.

After George Whitman’s daughter, Sylvia Beach Whitman, took over the store in 2003, the store became further involved with the contemporary Anglophone literary scene, launching the Paris Literary Prize, hosting famous authors for readings, and opening a bake shop and café next to the store in 2015.

George Saunders, the author of the story collections “Tenth of December” and “In Persuasion Nation,” is perhaps the best example of this evolution of Anglophone literary culture at Shakespeare and Company, a culture that has grown increasingly politically aware in recent months. The store’s first event in 2017 was called “Literature Under Trump.”

Many of the guests at George Saunders’ reading made the pilgrimage to Shakespeare and Company either to hear more of Saunders’ sardonic wit, or hear about his stance on American politics. While Lincoln in the Bardo is a novel about a metaphysical journey through purgatory and history, it is especially relevant at the beginning of the Trump era.

“Those of us who got blasé about democracy got a wake-up call,” he said, in response to a question from an audience member about how to situate novel-writing in the Trump Era. Saunders voiced his frustration with the progressives who got lulled into complacency, but also suggests an alternative to despair.

One woman from the audience asked Saunders how he felt writing can make a difference, and if he ever felt like writing a giant “I-told-you-so” to all those who doubted his opinions on Trump. Saunders resisted the easy answer.

“I think about what writing has done for us,” he said. One shouldn’t fault the novel for failing to change the world, because “that isn’t really how the machinery works.” Instead, Saunders urged the audience to think about individual reading experiences.

While he knew his books wouldn’t save the world, he said that he believes in the awe and wonder they provide. These feelings, to Saunders, are the point. “The most powerful feeling in the world,” he said, “is to have totally unbounded love.”

At this, George Saunders seemed to remember where he was, and why it was special.

“Generations of people have come to this beautiful place, this beautiful city, and this building,” he said. “Generations have come because they kept wanting to learn more.”

In situating literature as an antidote for close-mindedness, Saunders connected nationalism and prejudice to the inability to empathize with others unlike us, and our inability to move beyond our projections. To Saunders, reading is central to this process of resisting projection. The worlds within books are important, only insofar as they can help illuminate our own.