A NOTE ON THIS PAGE

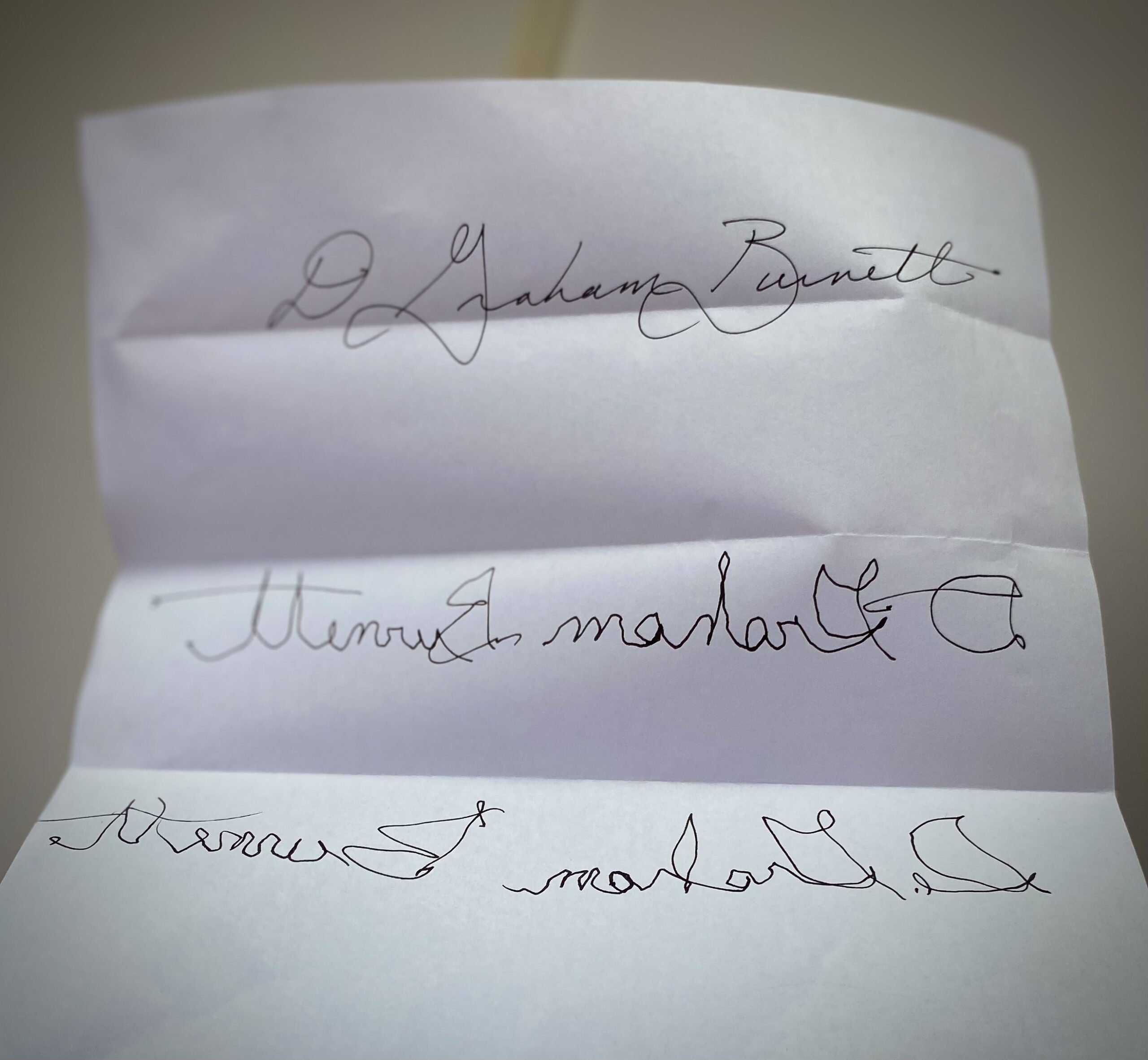

The entries on this page reflect an effort to document the unfolding of the NEW SCHOOLS seminar taught at Princeton in the Spring Term of 2023 (taught by D. Graham Burnett and Jeff Dolven; launch syllabus here). Entries below follow a basic format: first, several pre-class-meeting “reflections” on the week’s reading (by students in the seminar, initialed at the end, to indicate authorship); then post-seminar reflections by Burnett & Dolven. Throughout the thread everyone involved in the course has added comments and links, images, etc. We use the following convention for comments: green text and single brackets for first-order interventions; blue text (and double brackets) for comments on comments; and violet text (and triple brackets) for comments on comments on comments (later we added orange for fourth-degree comments). Initialing comments is standard. For an earlier example of all of this at work, consider skimming the chat thread from this course, taught several years ago.

We used the thread below for Weeks 1-8, after which the seminar format switched to student presentations on specific “cases.” For more on that, go here.

DGB & JD

* * *

CLASS 1

Readings

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “Land as Pedagogy: Nishnaabeg Intelligence and Rebellious Transformation,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society 3, no. 3 (2014): 1-25.

Jonathan Lear, A Case for Irony (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), pp. 1-41.

A few thoughts about our first session. First, just a thank you. It felt good to launch. And (perhaps you could sense this?), there is something very special for me to return to the classroom with my friend Jeff – we last co-taught in the pre-pandemic era. And that feels a little like a different world…

But we are in this world now, and in it we are committed, again, to what can happen in a classroom – and beyond it!

So here we go…

We got underway by circling the room, and letting everyone say a few words about a “teaching situation” that informed the desire to become, oneself, a teacher (assuming, of course, that this is a way we thing about ourselves – we tried to leave that a bit open…)

The results were rich. So interesting to hear from everyone about “scenes of instruction” that left important memories. I began, myself, by talking about “the seminar NOT TAKEN” – Wittgenstein with the charismatic Victor Preller. His Aquinas seminar marked me, but I was too afraid to continue with him into the twentieth century. Had he done something wrong? No, not at all. But his power as a thinker/teacher, his passion, left me worried I would be wobbled by the walk with him into material that did not as easily align with my (youthful) soul.

We went full circle, too, because by the time we got around the room, Jeff finished the loop by talking about the Wittgenstein seminar he DID take – with none other than Jonathan Lear, the author of one of our readings for the session. And Jeff affectingly invoked the way that Lear split the difference between philosophy and psychoanalysis – carefully declining (as Jeff experienced it) to offer the positive confirmations of insight that are at least one key way to conceive the teaching role. Thrown back onto himself, frustratingly, Jeff was left to wonder about what in what he was working to know was his own affair.

Or anyway, that was how I heard the story. And it put me in mind of the lovely introduction to Jeff’s first book…

[emoji smile]

Right. So. I am not going to try to summarize all of your powerful and beautiful “primal scenes” of teaching and learning. Maybe Jeff will! But I can list a few things that ended up in my notes – stuff to which, perhaps, we will return:

-

-

- Comic/Radical Permission

- Virtuosic Command (of the material)

- Softness (this one gets a star – worth returning to that; what does it mean?)

- Generosity

- Ideality (some teachers became role models, or conveyed a sense of a possible/desirable “form of life”)

- Community building

-

Again and again we heard (and articulated) versions of the notion that a teacher had played a role in helping us “take responsibility” for our own formations/educations. Or had made us feel that we ourselves were “being taken seriously” as thinkers or readers or makers. I am reminded, too, that R.S. slightly pivoted on the question, saying (as I heard him) something along the lines of “it is hard to pull out a ‘moment,’ since teaching and learning has been, for me, so much about relationships.” This, too, stayed with me.

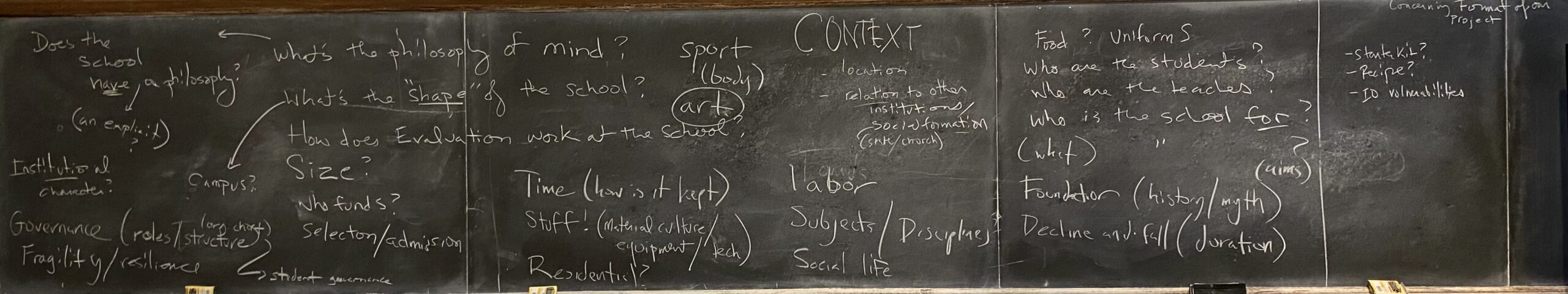

We did a turn out into the nuts and bolts of the course – the syllabus, the assignment, the aspirations (only later did we ponder the etymology of this word…). I’ll pass over all of that here, only underscoring that our idea is that across the first half of the class we will use our history and theory readings to help us build out, collectively, a kind of “template” for thinking about “cases” of educational innovation (“New Schools”). It will be that template that we will all then use, in the second half of the course, as we try to create a kind of library of comparable write-ups about the set of school-experiments that you choose as your final-project topics. More on all of that as we go…

*

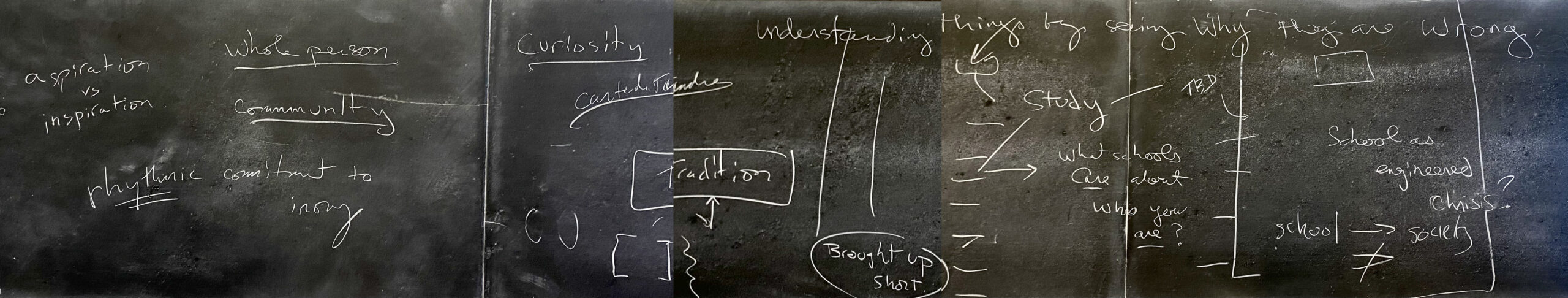

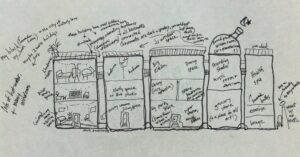

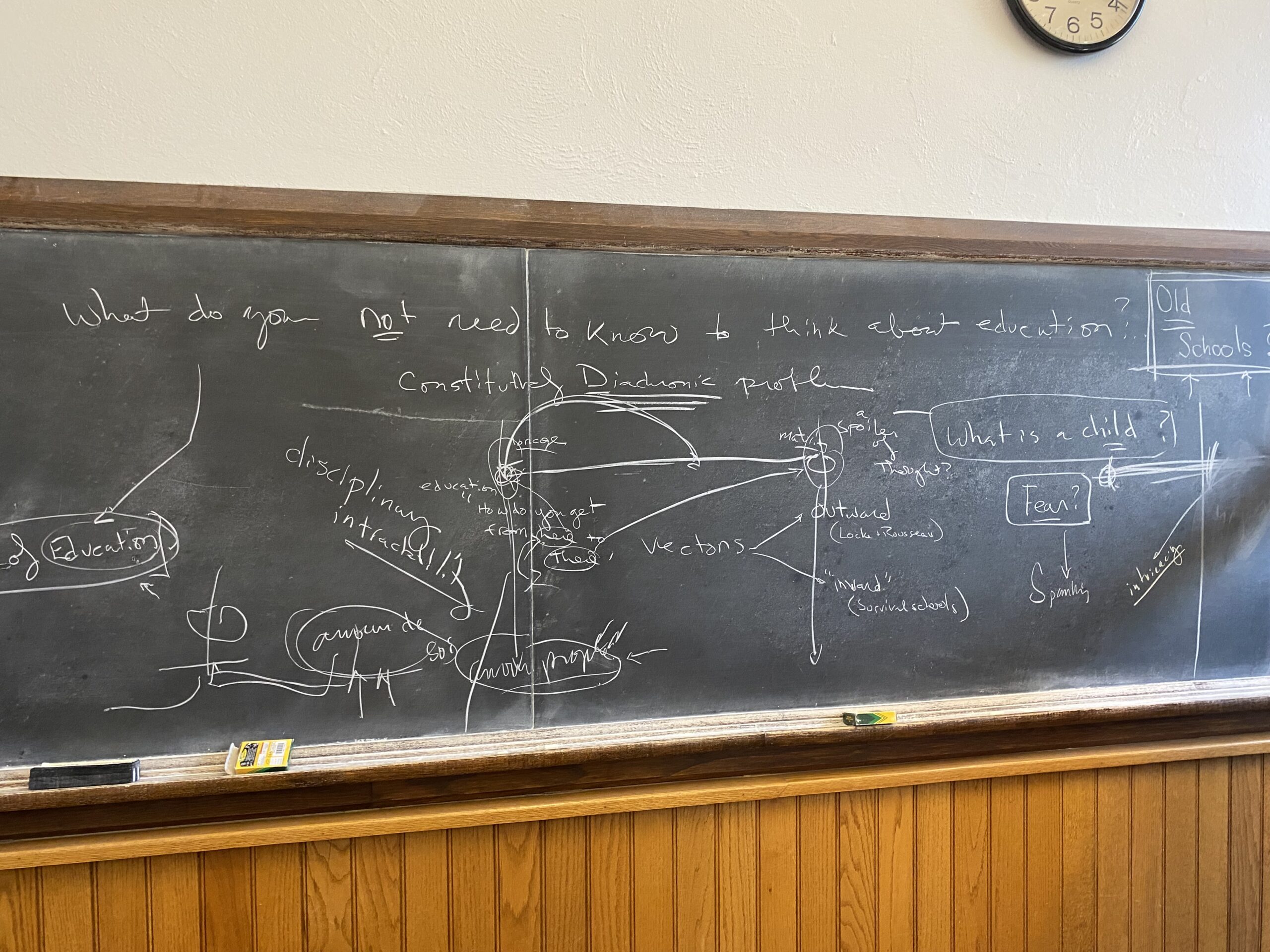

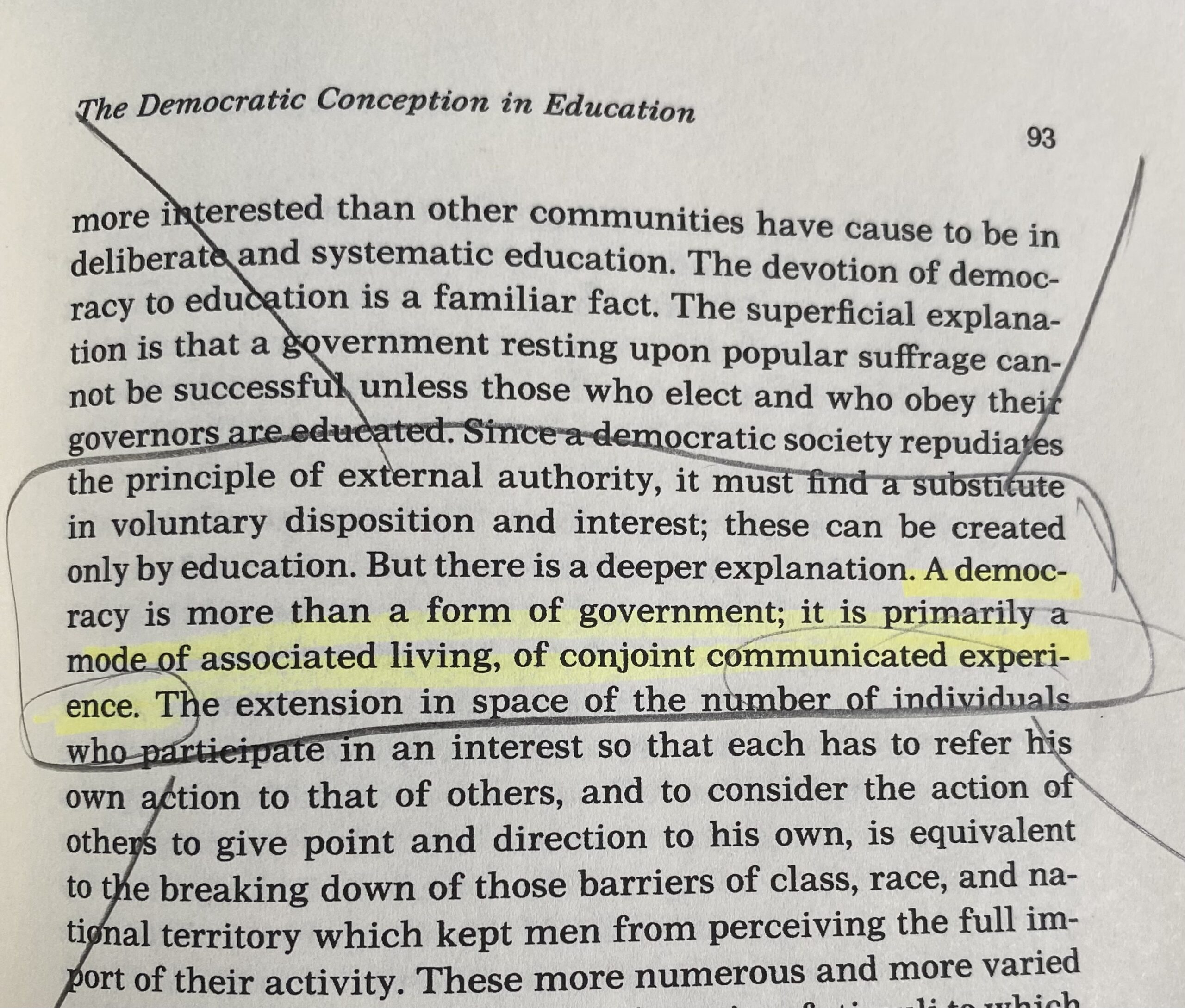

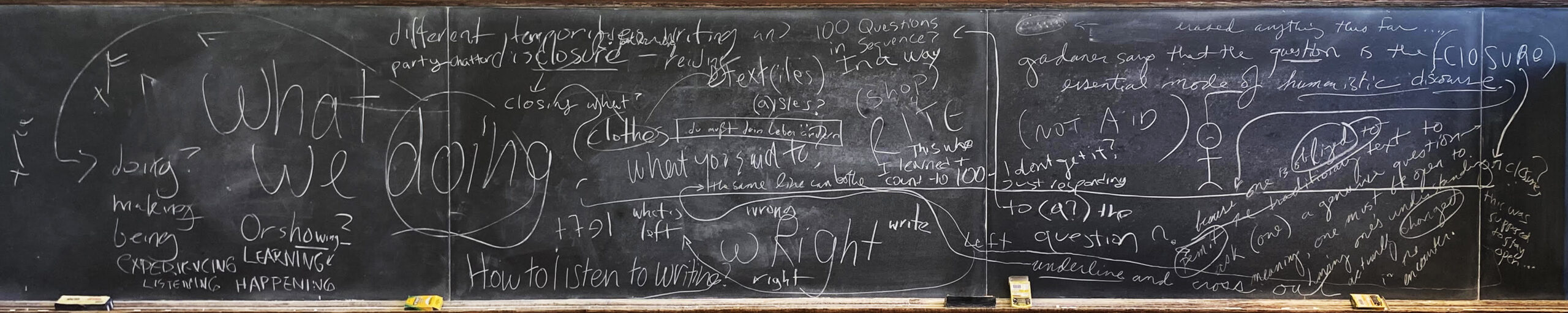

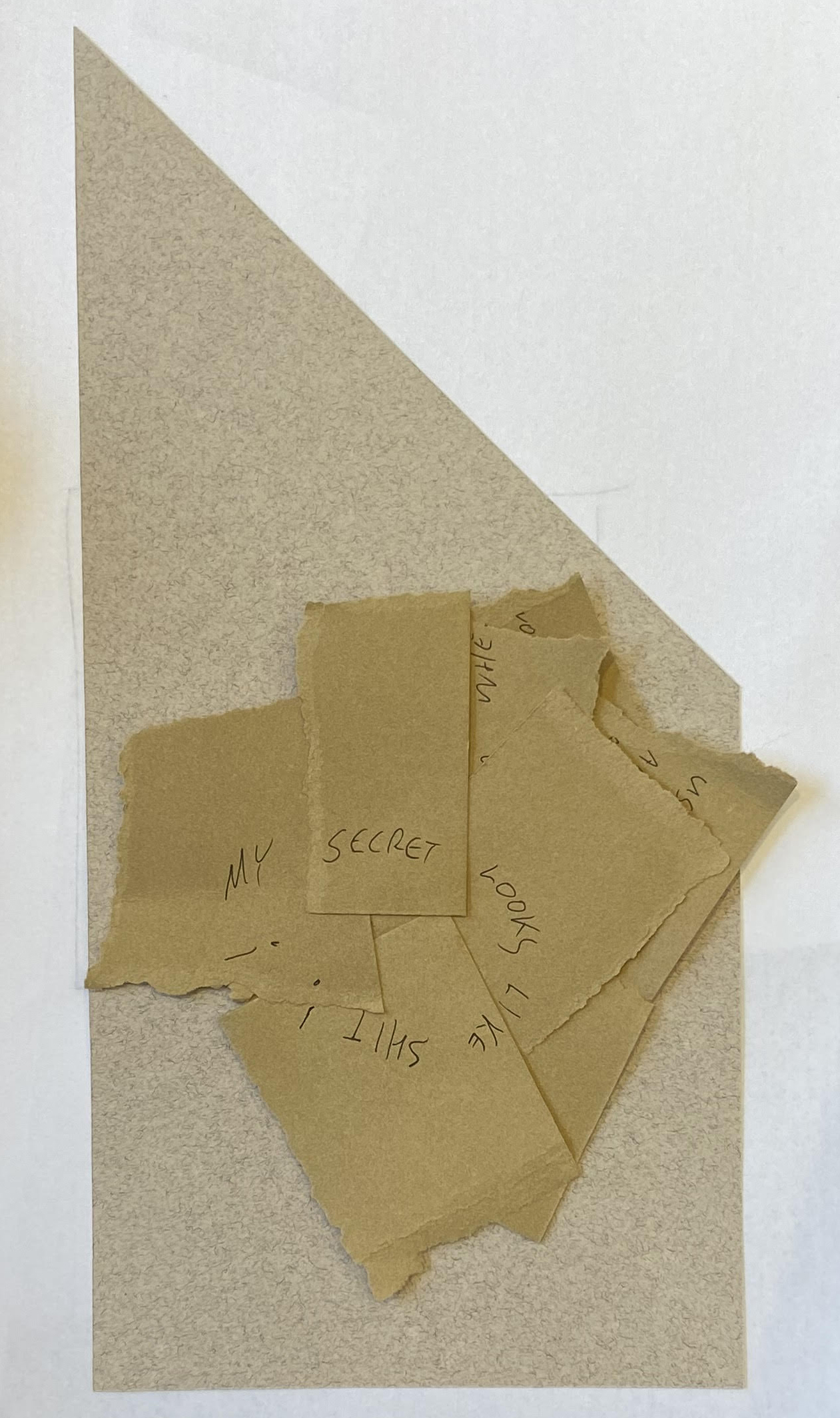

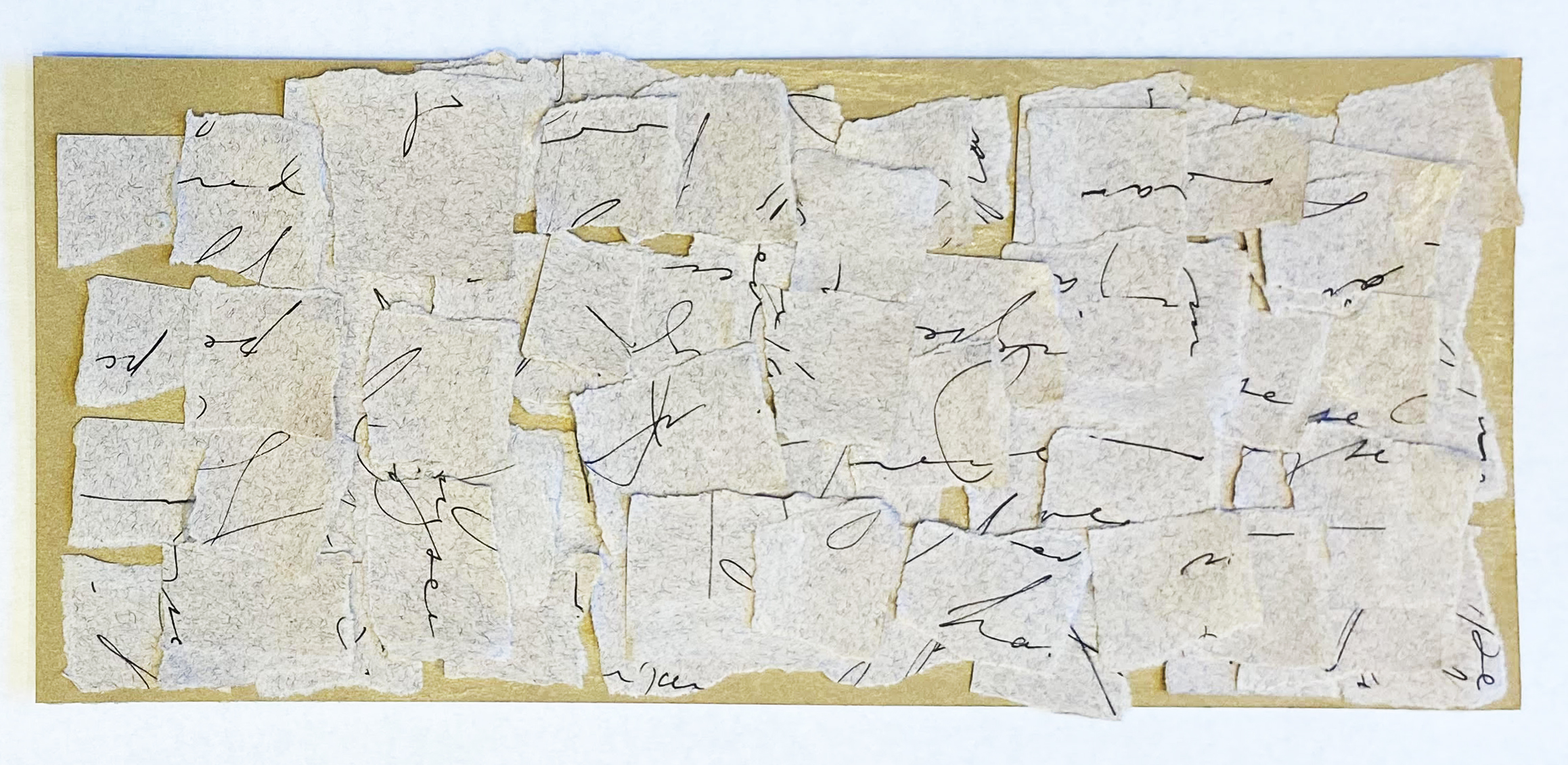

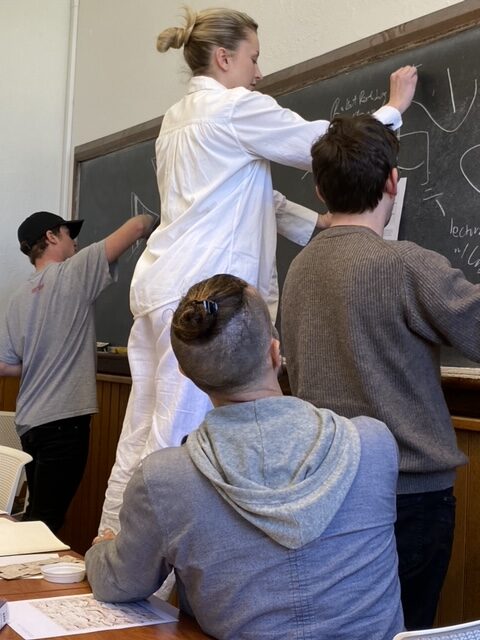

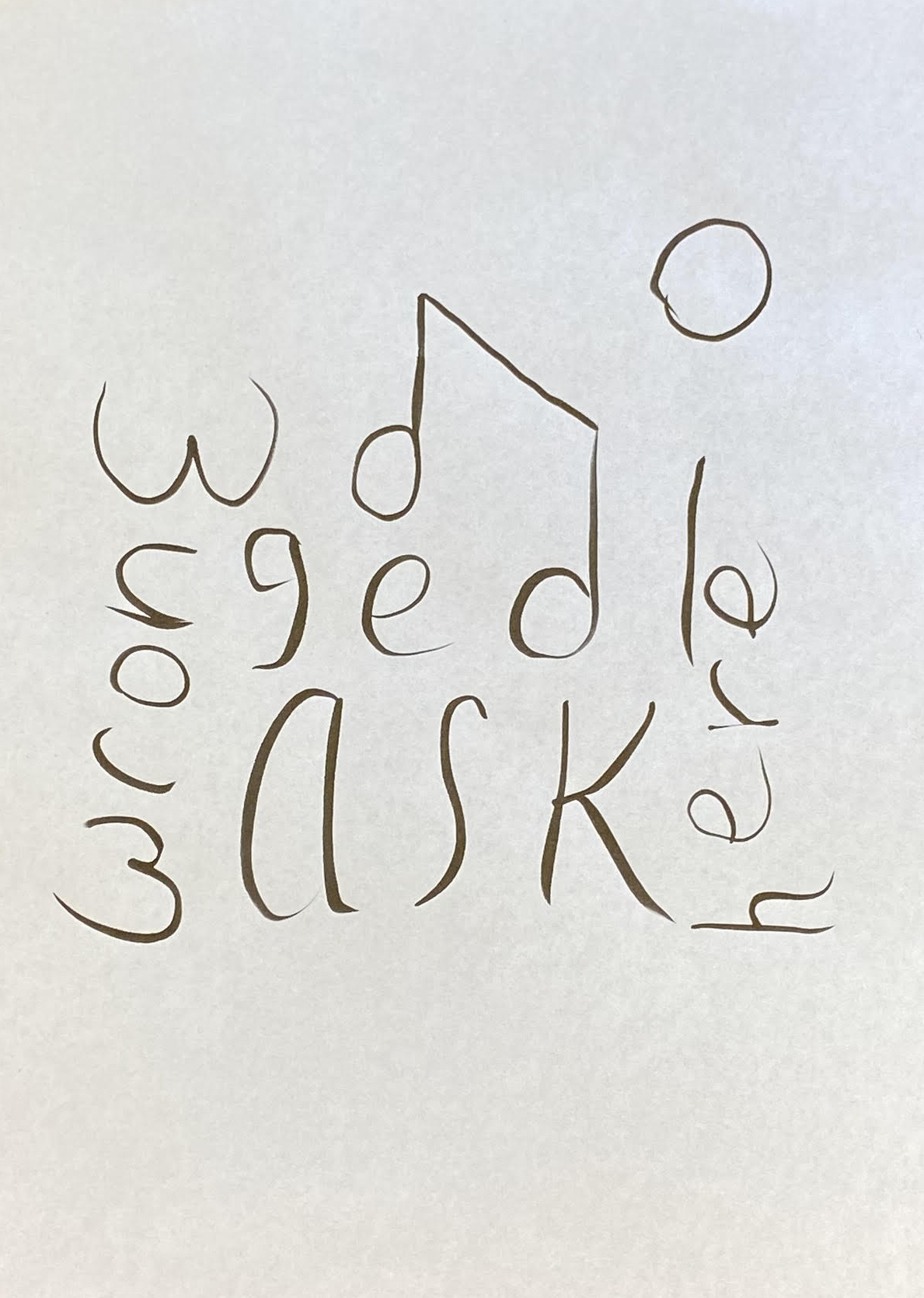

After the short break, we dug in on the Lear and the Simpson. A number of the terms that surfaced in that conversation ended up on the blackboard (I stitched together a photo of it, and have dropped it in above). It is worth looking back at those fragments. I find the line across the top quite touching: “Understanding things by seeing how they are wrong.” Sums up a significant thread through our educational forms, no? And yet, on that course, the process of understanding becomes a species of alienation. Or no? Hmmm.

We spent time on the relationship between the two texts – which can fit together in a number of ways. Certainly one temptation was to ask whether a figure like Nanabush belongs in the sequence of (canonical) deep-ironizing teachers surfaced by Lear: Socrates and Kierkegaard.

I will perhaps add my reservation about the Lear (which I much admired): I think I was not convinced, in the end, that he successfully defends the idea that “the ironic experience” is in fact anything other than another iteration of (garden-variety?) “critical reason.” Or, to put it another way, I am not sure one can hold space for a god-struck erotic uncanniness unless one is willing to invoke an effectively theological posture. What for me separates Lear’s left column (“normal” social scientific modes of recursive critical scrutiny) from the right column (“which invokes the aspiration,” as he puts it) is exactly the metaphysics he explicitly disavows, when he writes, “a life exemplifying any of the categories in the right-hand column is neither ineffable nor supernatural” (p. 26).

So I am “with” him, I think, in the broadest sense: we do indeed need to maintain ways of thinking and doing (teaching and learning) that can parse his left column from his right. And I am also with him that his ironic heroes can be understood to be using irony to subserve ideality (rather than merely distancing themselves and others from ordinary conditions of being). But he seems to think he can bring us with him on these claims without reference to metaphysics. And that seems to me to be incorrect.

But perhaps I am wrong?

What can surely NOT be wrong is Simpson’s powerful exhortation on page 18: “If you want to learn something….Get a practice.” I think that deserves to be boldface:

GET A PRACTICE.

-DGB

* * *

That opening round of everyone’s scenes of instruction could be a kit for the whole course. Graham is right!—I ended up making a short catalogue, catching everybody I hope. I’ll just echo him first, though, what a joy (and kind of a relief) to be back together with him, us two and us too, all of us.

OK: let me just meander through my memory, and my notes, make a few observations, and pull out a few big questions that we’ll likely find ourselves following. One common theme: almost everyone’s example turned around a particular person, almost always a professional teacher; methods, institutions, other students were variously involved and entailed, but it was a gesture, a tone or touch, a particular white seersucker suit that seemed to come first to mind. (Do schools matter? Or only teachers?) We will often be reading about pedagogies and institutional structures, and we will have to learn to recognize the teachers that inhabit them, and reckon whether and when we can parse charisma and experience from syllabus and method. (Schools will often want to disavow their dependence on particular teachers; when should we credit them?) PH and EH between them raised some version of this question about an architecture seminar that seemed to succeed for being both critical (“how can we be more radical?”) and also very personal. FS gave us a teacher who was gruffly generous with students’ mistakes. (What counts as wrong in a school? If anything?) ZM spoke affectingly about a teacher’s demanding “softness”; what is that quality, and why should it make a difference? Sheer enthusiasm for the subject was transformative for LD. Sometimes these teachers taught clear lessons, sometimes they offered themselves as examples, as HB’s teacher did, a cool, charismatic intellectual interloper in an academy of athletes. AK’s intaglio professor was an example (or maybe even an allegory) of disciplined craft. (What is the pedagogical role of imitation, implicit or explicit?) RS saw the meaning and value of study in relationships developed over time, but he also wondered whether anything in those relationships could be isolated as teaching. (Is there such a thing as teaching? Or only learning?) Freud does place teaching among the impossible professions, with government and, of course, psychoanalysis.

Other moments mixed personal tribute with a particular incarnation of method. So, NB’s professor with his gift for generous paraphrase. (What is the pedagogical role of translation?) A couple of teachers impressed for the sheer mass, even completeness, of their knowledge, as for CA. (What does a teacher need to know to teach; what does a student need to know to (have) learn(ed); what counts, in a given school, as knowledge?) NI was treated to a structuralist Simpsons. (What is the pedagogical role of analysis—cutting things into their parts?) There was also some reflection on seriousness, and being taken seriously, as with CB’s no-cocktails MFA seminar and MG’s extra-curricular, after-class reading list. We may want to ponder the weight of that word, serious, as we go. CA emphasized the lesson of perseverance from artists she has worked with. CF told us about a teacher who allowed her to separate the study of architecture from glamorized suffering. (Should school be hard? What kind of hard? Why?) If there were any exceptions to this focus on teachers, perhaps they came from TU (whose scene of instruction was a community in Buenos Aires) and JM, whose teacher’s open-ended, borderline-irresponsible assignment forced him to take is education “into his own hands.” (What does learning have to do with independence?)

Along with those questions, I’d like to keep in mind, as well, a couple of basic ones that came up, about the individual (How much of life does the school concern itself with: technical knowledge, political commitment, personal comportment, etc.?) and about the school in its context (What is the relation of a school to its society: preparation, critique, model, etc.?). Above all though, I hope we can carry forward the affecting thoughtfulness and openness of these stories. Everybody in a schooled society is shaped in the most profound and intimate ways by who taught them and how and where. For those of us who want to be teachers, the complexity of those influences is compounded. If we can stay that close to our experiences, and our feelings—we will do well.

*

OK: on to our discussions of the readings, Lear and Simpson. DGB and I had an intuition that they would make a good pair, and as I prepared for class I felt that intuition confirmed: we could start out with a bracing contrast between Simpson’s immanent, continuous place-pedagogy, and Lear’s transcendental irony; between the view from here, and the view from nowhere (two different places to build your school); between learning as a way of life, and learning as an interruption of life. So I was surprised that RS got us started with the opposite idea: roughly, that these two essays were quite alike, in that they both endorsed tradition, and were in some sense conservative. For Simpson, that meant the cultivation (and reconstruction) of Nishnaabeg ways of learning. For Lear, transcendental irony, for all of its abstraction from practical identity, was nonetheless potentially, indeed ideally, loyal to it. There was some dissatisfaction in the room on both counts, and that will be worth thinking about as we go. A couple of different accounts of “radical” may be in play. Do we mean by that word a return to a root, and if so, is that a historical root (some prior, effectively originary cultural formation) or a fundamental principle (for example, justice, or equality)? Or does it (also) mean for us a break and a novelty, a new beginning?

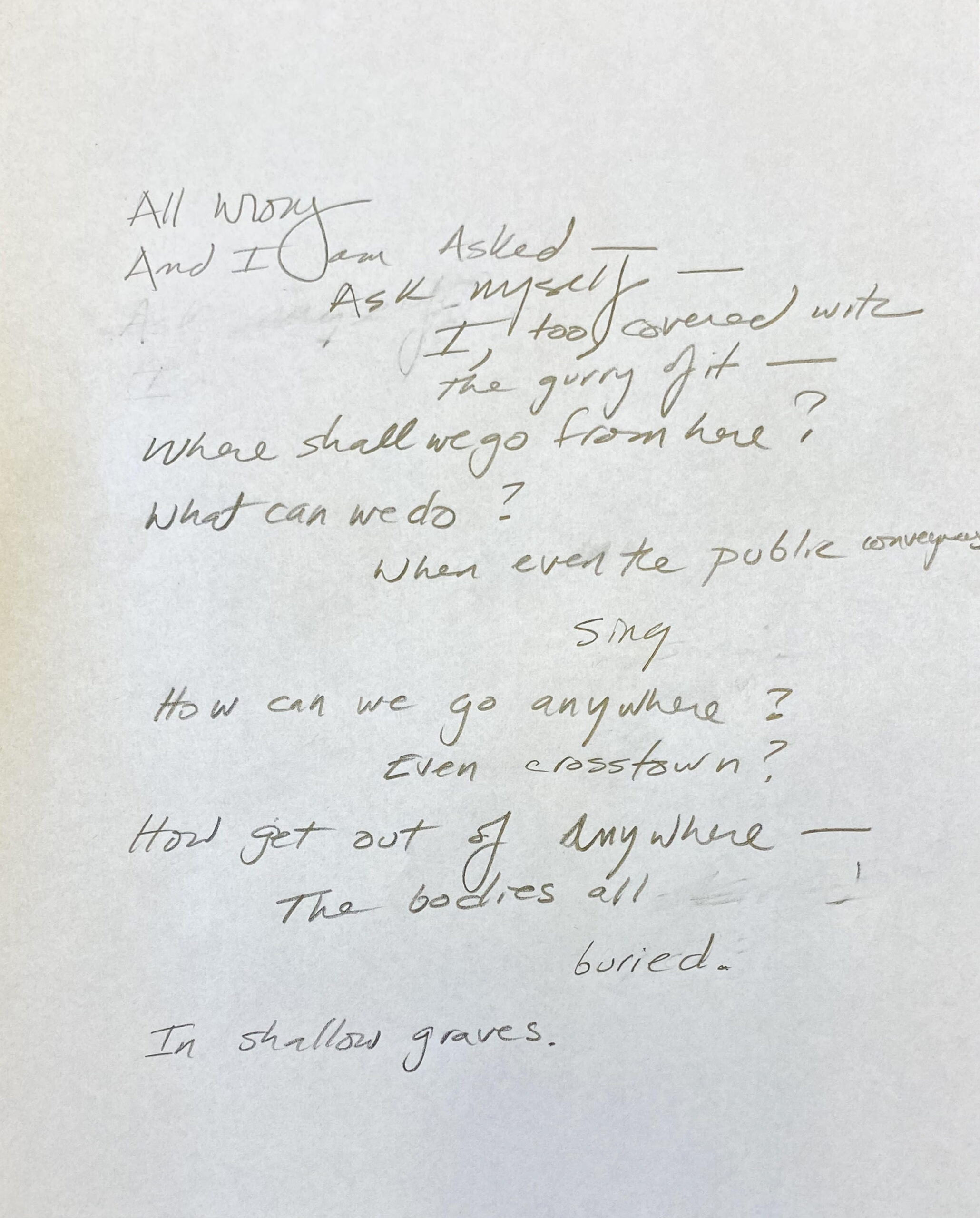

We puzzled over the way Lear’s conception of irony seemed to cross over into theology. “Ironic existence need not show up in any particular behavioral manifestation—though how one inhabits the social pretense will nonetheless be transformed” (30). As I said in class, this remains strange for me to encounter from the man who taught me Wittgenstein, given W.’s skepticism of the tendency to posit inner states that have no knowable expressions. It struck DGB and others as metaphysical, not to say theological. How do you make the apparently categorical leap from ordinary into radical irony? [yes – or distinguish “conventional” reflective/critical rationality from the “higher” (?) form of defamiliarizing distance at play in Lear’s big-I Irony – DGB] And for that matter, how do you get back? How do you travel between here and nowhere? (Let alone, commute?) It should be said that Lear does keep returning to the experience of radical irony, of being “grabbed” or “shaken.” Maybe we do well to hold on to that, to a feeling that is distinctive and powerful, a feeling that we often want to explain as though it were a moment of detachment, abstraction etc., or even ecstasy, in the sense of standing outside. (And in that case, his distinction has some force: radical irony, that exhilarating vertiginous anchorless clarity, is a different feeling from the self-dissonance of vernacular irony, with its shades of knowingness, sarcasm, resignation, etc.) Does education require such moments? Or even consist in them? Does teaching, does learning? (In the way that poetry is something that happens only occasionally in a poem?) Just one more thought about grabbing and shaking—who grabs, who shakes? Lear is definitely not talking about corporal punishment, but the role of such main-strength somatic interventions in schools is a pretty ancient business. Hmmmmm.

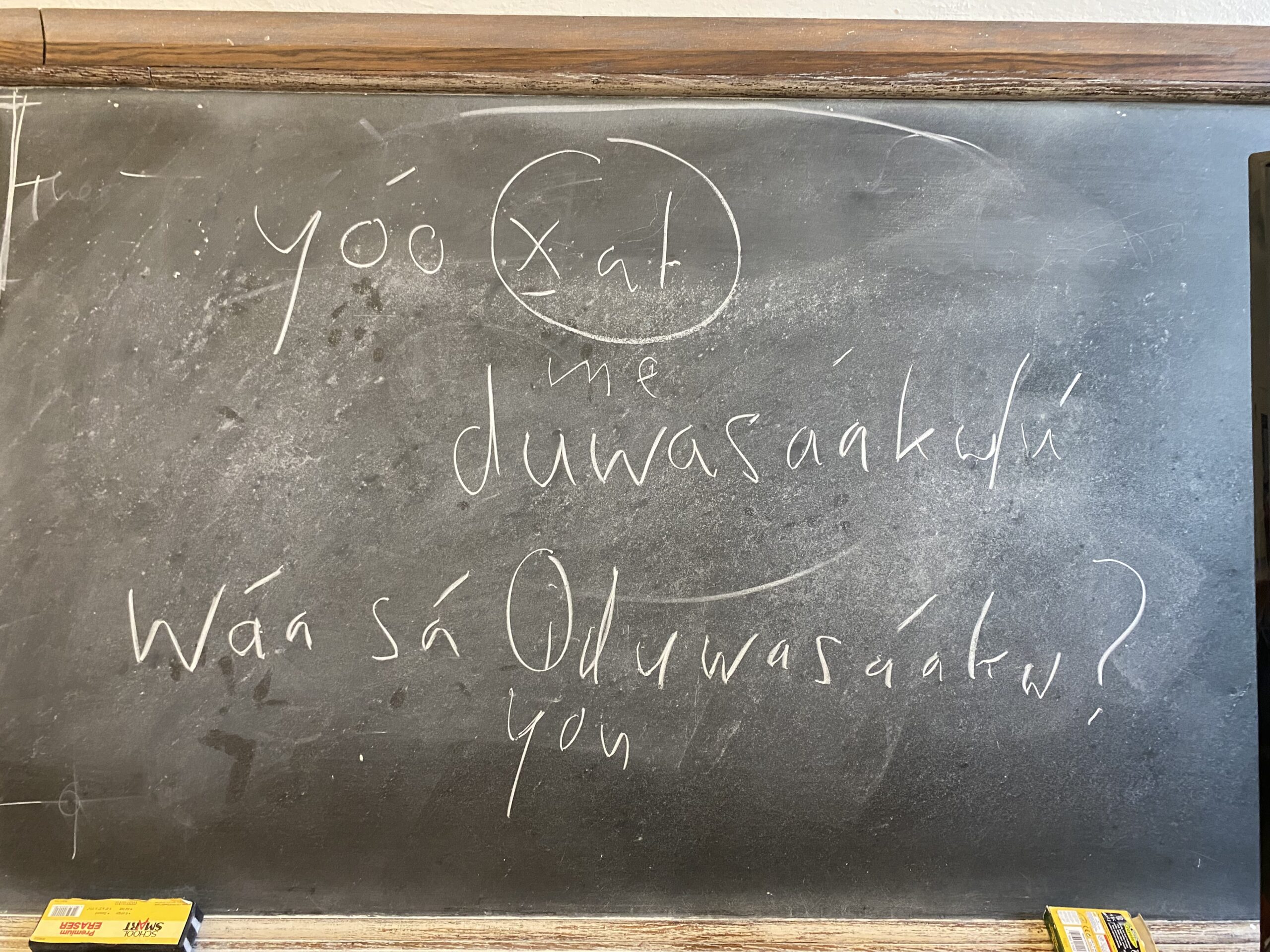

[DGB paused on the phrase “to bring someone up short.” There’s something wonderful about this expression. It runs into itself, rising to diminish. Drop “short” and it’s “to bring someone up,” to edify. Keep it, and it means to give someone pause, to make them stop. Sudden perplexity, open-mouthed inadequacy are a leitmotif in much of the classical pedagogy literature we have read. But in Sitka, we heard another phrase which means the same but also a completely different thing: “to hold someone up.” I’m struck by how these wordings encapsulate two very different pedagogical models, both built around the potentiality of the break. RS]

We just scratched the surface of Simpson’s argument about land as pedagogy (as it were). We can return to it, as a description of a kind of pedagogical immanence. To take context-as-curriculum is to assume that nature and culture, as an integrated, mutually attuned totality, will train up a young person with lessons appropriate to their age as they go. (“Train,” “lesson”: imperfect words.) There are some particular ways of coming-to-know to study here: imitating animals, for the younger; and believing in advance, not after, for the older. But the force of the argument is a project of historical repair: it is addressed to the damages done by colonial pedagogy and society, and the alienation of the Nishnaabeg from the land. So, a number of binaries imposed by coloniality are undone, for example, the distinction between narrative and theory. A story can be a theory, and theory can be for everyone, a form of integration into community rather than an abstraction from it. “The implicate order provides the stories that answer all our questions” (12). And learning seems to happen not as a result of discipline and effort, but as an opening in spaces of leisure and happiness. (Though Kwezens does have to answer her mother’s questions, and then demonstrate her discovery to the community—both are forms of evaluation, and come with some anxiety, which is managed by love and care and also successful learning.)

It’s worth asking how Simpson wants her larger academic audience, outside the tribe, to read the essay. Does it explain why efforts should be made to grant the nation (a word she uses often) the autonomy to revive a version of this traditional pedagogy? Does it offer a program that anyone could follow? Between those two, are there lessons or maxims (e.g. about proceeding from belief rather than doubt, or about the role of imitation) that are applicable in other school settings? She is alert to the ironies here, though as CA pointed out, that doesn’t mean she has an answer to them.

A final word about Nanabush. I want to keep after that question of the place of the trickster in the school, and the affinities between Nanabush and Lear’s trickster-heroes, Socrates and Kierkegaard. Is Nanabush as trickster of a piece with the pedagogy of land? Is he a supplement to it? Does he in some sense contradict it, point out the insufficiencies of an immersion in what is, the need for guile, concealment, wit, transgression etc.? And if he is an instance of contradiction—what do we make of that? We will be tempted throughout to be critical of the schools (institutional, theoretical) that we encounter, to prise open the way they contradict themselves, or our own values, or both. That’s not a reflex to banish by any means. It is a basic mode of understanding. Schools themselves will often claim to be critical. But the sternest negative-dialecticians will acknowledge that no cultural construction is without its contradictions. Managing contradiction is what culture is for. School too? We’ll want to get interested in the strategies by which various schools make their bid to resolve the antinomies of education, which might include that dubious distinction between teacher and student, between freedom and discipline, etc. etc. Sometimes critique will be the right instrument. Sometimes something maybe more like incubation: nourish these contradictions, and see where they lead us. Growing up, after all, provides ever new resolutions to problems of freedom and discipline, and growing up is (maybe?) what education is about. Contradiction is in itself a synchronic phenomenon and education is diachronic. Fortunately that’s what a seminar is for, to give what we study some time.

-JD

CLASS 2

Readings

Plato: Meno; Protagoras, excerpts (317e-328d, on teaching virtue); Republic, excerpts from Book II-III (367d-417b, on the polis and on imitation and arts), Book IV (419-445b, on the city and the soul), and Books VI-VII (486d-341b, on sophistry, and the allegory of the cave). The pdf’s here are from Plato, Complete Works, ed. John M. Cooper (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 1997).

Isocrates: Antidosis, in Isocrates I, tr. David C. Mirhady and Yun Lee Too (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000), pp. 201-264.

Bernard Stiegler, Taking Care of Youth and the Generations (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010), pp. 1-93.

Judy Chicago (and others), “Womanhouse” (take a look at the primary sources; watch the 40-minute film).

OPENING THINK PIECES (NB & RS)

I wanted to begin my post with a paraphrastic rendering of a scene from the Isocrates reading and move to a consideration of its relevance for our discussion last week about “practice,” the paradoxical commitment of education (in its radical and “conservative” manifestations) to both heterogeneity and homogeneity, and the faculties or psychic/cognitive processes for which teachers are responsible. Isocrates’s Antidosis instantiates and defends the practical limits of philosophical instruction against the twinned charges of impotent overpromising and corruption. The former camp argues that those lucky pupils who do go on to lead distinguished public lives owe their success to innate talents alone and, incongruously, that sophism itself seeks to flatten all qualitative distinctions between “the lazy” and “the diligent” (what in contemporary parlance we might call “equality” of outcomes). Against this group of critics, Isocrates defends the modest claims of genuine pedagogy: “We acquire knowledge through hard work and we each put into practice what we learn in our own way” (15.201, p. 243, emphasis mine). This line of argumentation, Isocrates says, both disingenuously inflates the normative value, or intention, of such instruction (everybody who studies with Isocrates ought to and will become an Eunomos or Lysitheides) and unfairly diminishes its propitious effects. In other words, Isocrates maintains that he can aid those with natural talent achieve a degree of excellence hitherto impossible, while those lacking such congenital facilities are, through study and practical application, able to rise above their gifted, but uncultivated, counterparts. To the second allegation, Isocrates contends that, besides the more obvious point that proselytizing unscrupulous behavior (even cleverly or through dissemblance) would destroy a teacher’s reputation almost instantly, man’s natural corruption renders any education in its exercise unnecessary, “Furthermore, why would [any student] waste money for the sake of evil, when they can do evil whenever they want without paying anything? No one needs to learn such deeds; he only has to do them” (15.225, p. 247).

I wanted to isolate Isocrates’ first defense against those critics who insist that his teaching must necessarily lead to (again anachronistically) equality of educational outcome. He insists that he never promised any such thing and, moreover, that the diverse gradations of talent, fortune, and practical experience ensure that, “From every school only two or three become competitors, while the rest go off to be private citizens” (15.201, p. 243). Later, however, he describes such education as resembling the other practical and bodily arts in its common objective, coming to mirror their instructor through a dual process of individual-practical application and mimesis, “All those who have had a true and intelligent leader would be found to have so similar an ability in discourse that it becomes obvious to everyone that they received the same basic education. If they had no common character or basic technical training instilled in them, they could not have achieved such a similarity” (15.204, p. 244). Is the distinction here a simple one between content and form? What unites the “naturally talented” and those C+ students who “go off to be private citizens”? Is it a shared commitment to the embodied practice of rhetoric, the psychic preparedness for and extemporaneous capacity to form judgments or opinions (doxa) in those “opportune moments [which] elude exact knowledge” (15.184, p. 240). Is this about the cultivation of dispositions and the capacity to “self-authorize,” in the words of later German idealists? I was quite taken with Isocrates’s general (though not unequivocal) demotion of philosophy to the level of other mechanical and bodily arts. In addition, he imposes clear limitations on its social and civic utility while defending its value as a precondition for virtuous public life and heeding attention to the intimate, bilateral relationship between speaking well (aesthetic and rhetorical perfection) and speaking truthfully, without reducing one to the other. It would be instructive to compare his views on how virtue is transmitted, its “teachability,” with those of Plato, Menos, Protagoras, and, to a lesser extent, Stiegler.

As such, I also wanted to briefly raise the issue of the generational transmission of ethical commitment through the law (and its derivation from the polyphonous and protean symbolic order, treated in starkly similar ways in both Isocrates and Stiegler, their normative commitments notwithstanding) and the relationship of the teacher to the burdens, judgment, and aporia of history.

In addition, we are presented this week with several different pedagogic forms, rhetorical strategies, modes of emplotment, and instruction, and ways of arriving at the telos (or lack thereof) of that instruction: from the classic Socratic elenchus, to Isocrates’s idiosyncratic deployment of legalistic discourse (which helps him both make his substantive case for philosophy while immanently critiquing the infirmity of “juridical speech” itself), to Stiegler’s “traditional” (though polysemous and erudite) academic monograph, to Judy Chicago et. al’s spatial and environmental intervention. What can these different means of intellectual expression tell us about the multimodal nature of learning and what types of engagement (sensorial, psychic, emotional, etc.) do they demand?

On a completely unrelated note, I also wanted to include a brief list of my favorite movies about education, schooling, expertise, “responsibility” in the Stieglerian valence, etc., along with their Letterbox’d descriptions, for your perusal!

“A group of academics have spent years shut up in a house working on the definitive encyclopedia. When one of them discovers that his entry on slang is hopelessly outdated, he ventures into the wide world to learn about the evolving language. Here he meets Sugarpuss O’Shea, a nightclub singer, who’s on top of all the slang—and, it just so happens, needs a place to stay.”

The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964)

“This biblical drama focuses on the teachings of Jesus, including the parables that reflect their revolutionary nature. As Jesus travels along the coast of the Sea of Galilee, he gradually gathers more followers, leading him into direct conflict with the authorities.”

“Documents the lives of infamous fakers Elmyr de Hory and Clifford Irving. De Hory, who later committed suicide to avoid more prison time, made his name by selling forged works of art by painters like Picasso and Matisse. Irving was infamous for writing a fake autobiography of Howard Hughes. Welles moves between documentary and fiction as he examines the fundamental elements of fraud and the people who commit fraud at the expense of others.”

[Hey! I freaking LOVE this movie, and taught it in The Art of Deception class a while back… -DGB]

“A group of bored teenagers rebel against authority in the community of New Granada.” [this movie is insane]

The Decline of the American Empire (1986)

“Four very different Montreal university teachers gather at a rambling country house to prepare a dinner.”

“An unemployed Brit vents his rage on unsuspecting strangers as he embarks on a nocturnal London odyssey.”

“Steve Clark is a newcomer in the town of Cradle Bay, and he quickly realizes that there’s something odd about his high school classmates. The clique known as the “Blue Ribbons” are the eerie embodiment of academic excellence and clean living. But, like the rest of the town, they’re a little too perfect. When Steve’s rebellious friend Gavin mysteriously joins their ranks, Steve searches for the truth with fellow misfit Rachel.”

“A high school teacher’s personal life becomes complicated as he works with students during the school elections.”

“An Ivy League professor returns home, where his pot-growing twin brother has concocted a plan to take down a local drug lord.”

-NB

* * *

Jeff and Graham were not kidding when they warned us that assignments for this course may require us to adjust our habits of reading. How do we read Plato’s Socratic dialogues, or Isocrates’ Antidosis? Both are highly mediated textual artifacts that complicate, if not wholly block, our desire to extract chunks of knowledge out from the play of presentation. How about Bernard Stiegler’s Taking Care of Youth and the Generations? This is a text that mobilizes the genres of treatise, plaidoyer, call to arms, and “think-piece,” in the effort to explode the firmament of petrified ideas about schooling and to reconnect us to its vital roots: the formation of an integrated (‘transindividuated’) self and society by the techne of attentive care. And what do we make of Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s film Womanhouse? How does this filmic reverberation of a site-specific art installation, and the feminist collective that emerged with it, document the pedagogy of the place (to adapt Simpson’s term) in practice?

There is a problem, at least for me it’s a problem, of approach. I don’t think this is only a question of how to cope with the multiple genres/media of our sources. It’s also not necessarily an issue with their quantity. To be sure, when Graham and Jeff gave their fair warning, they were referring to the practice (apparently, it’s routine in Dickenson Hall) of assigning more books per week than I have fingers per hand with which to read and write about them. But I understood their remarks another way, too. For the problem of “how to read” is baked into the premise of this course. To contemplate “New Schools” in an old-school environment is almost by definition going to be self-reflective. So, let’s think about the “Sources and Authorit[ies]” of “Received Wisdom” (to speak with, and slightly tweak, the syllabus heading for this week) as they appear to us in the time and place this seminar. (Well, seminar blog, really.)

I’ll focus in my “think piece” on the Socratic texts, especially Meno. What kind of “New School” do we find in a text like Meno? We might start by observing that a Socratic dialogue is not like most other texts. It is certainly not like many texts we would normally call “scholarly,” i.e., texts befitting of those engaged with schools and schooling. (Let’s put aside, for a moment, the interesting speculation that Meno was supposedly the first text on the syllabus at Plato’s Academy in ancient Athens; though we might wonder that Plato did start a school, in fact; I don’t think we can say the same about Socrates, though many might claim to be his students.) The issue is, and I think it’s no trivial point, that a Socratic dialogue does not speak for itself. Socrates (forget Plato) doesn’t communicate directly to us as readers or hearers of the dialogue. At the same time, we can assume from entrances like Anytus’ (89c ff.) we – people like us – are ‘implied’ by the texts as living participants (invited guests, as it were, like Meno) in the dialogic space. But what kind of participants are we, and what kind of space do we enter and make when we reenact the dialogue in reading?

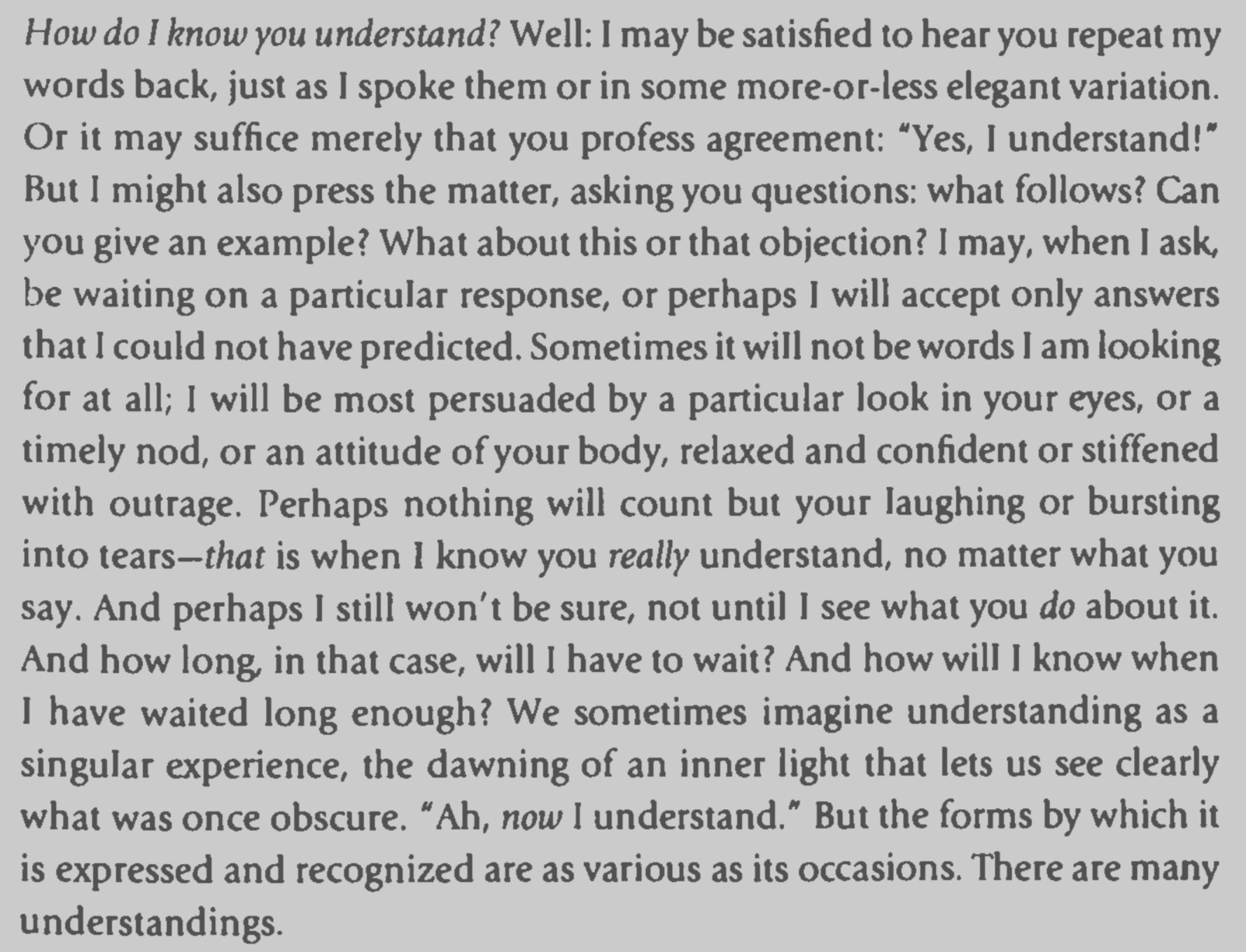

It’s not original to observe that Plato’s use of the dialogue form is of a piece with its ‘content.’ Already Aristotle pointed out that the Socratic dialogues are not apodictic but dramatic works and “akin to mime” (Poetics, somewhere). But we might then ask ourselves, of what is dialogue an imitation, a mime, a gesture? What is Meno (the text) doing? It’s helpful (as least to me it is) to think about Steigler’s thought that attention arises through certain “technologies” (or “techniques”). Of course, lots of people talk about a “Socratic method,” and supposedly some of what goes on under that name bears some resemblance to what we read in this text. But I’m struck by something else, and it is the ‘situatedness’ of the dialogue as an encounter between two individuals, rather than a battlefield of ideas. After all, the text is titled (apparently authentically so) Meno. It’s not titled after its theme, i.e., “Virtue,” even though it could have been, and like the Republic was. This seems important because it invites us to think about what is happening to Meno’s soul, his psyche, throughout the drama of the dialogue. For instance, when he is being “torpedoed” (his word; 80a-b). “Who is Meno,” we might ask, as Socrates does, at 71b, the very beginning of the dialogue. While we’re at it, we might ask the same about Socrates, and be mindful of changes in our own souls/psyches, when accept his invitation to “seek[] together” what it is we are wanting to know (80d).

Thinking about how Meno can help us think about “New Schools,” I’d like to offer some questions to close. Who is the Socrates we find in the Meno? How would we characterize him (trickster? ironist? teacher?)? Can we discern something like a Socratic ethos on display in interactions with Meno (say, at 70a-73c, and 80a-81e), Anytus (89e-94e), and Meno’s slave (82b-85c)? Are there any positive models, or hints of models, of collectivity, any chances for empowerment, from these encounters? (Maybe let’s deal with the Republic excerpts, where this is an explicit topic of conversation, separately.) What do we make of Meno’s “dramatic arc;” does Meno end up where we started; did we witness something like learning, and if so, how was it brought about?

-RS

* * *

(POST-SEMINAR REFLECTIONS BY DGB & JD BELOW)

We had a lot to talk about today. And we launched from the two think pieces above, which so nicely move from the Isocrates to the Meno — and set us up with half a dozen good questions. We read both of them aloud (we won’t always do this), and used the occasion to put this chat thread up on the screen and look at it together.

(That also provided an opportunity to review the technics of our WordPress site, and to go over the nuts and bolts of the CMS. With luck, everyone should now be ready to post comments and references in here using our conventions. Let’s all try to do one intervention — however small! — by our next class meeting.)

We went into the Meno first, and our baseline question was, “what kind of teacher is this?” or, perhaps, “what kind of teaching is this?” Later, we would put the question differently: “is there a school here?”

As far as the last of these versions is concerned, I hazarded a negative. Plato, certainly, had a “school.” But Socrates feels like a gadfly, like an unusual/insurgent/charismatic singularity. One has little sense of “students.” Also, perhaps this is exactly to ask a crucial “NEW SCHOOLS” question: Do schools need students?

Bracket that. (Although it seems worth pointing out that Womanhouse would seem to be difficult to parse into teachers and students…) [CA note: Ya I agree with this. Womanhouse is a success in part because student is teacher; teacher is student. These binaries have no jurisdiction in that space. And, more food for thought; such a configuration of multiplicities can be found in one person and not only in one house, or school:

Carolee Schneemann, Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions, 1963]

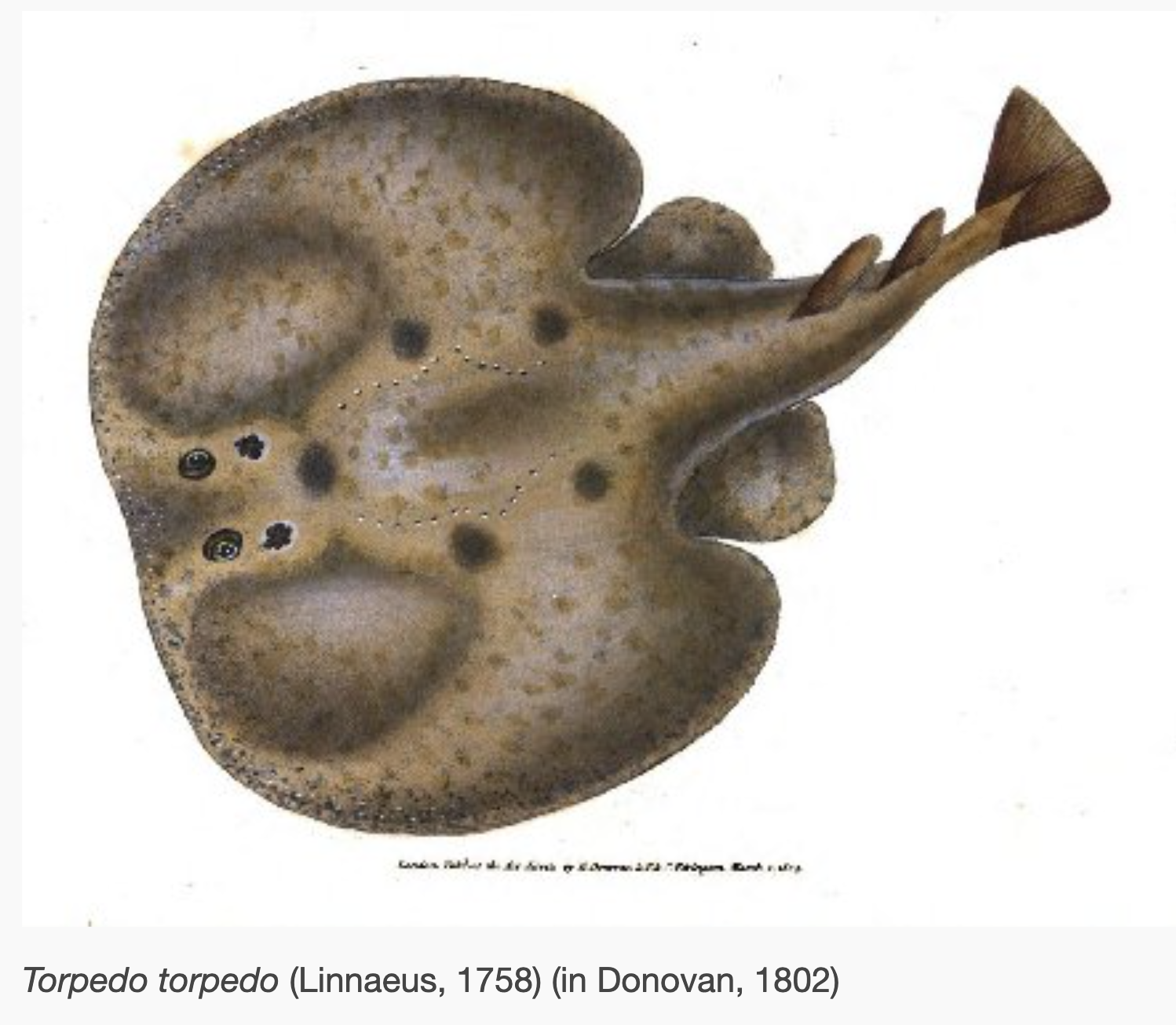

The Meno can be divided into two parts, and one can reasonably ask whether we learn more about Socrates’s pedagogy in the first half (the seemingly formal conversation with Meno himself) or in the second (where Socrates very definitely “performs” a lesson, demonstrating his theory of anamnesis by means of extensive parley with Meno’s slave). In the first part we catch a glimpse of Socrates the “torpedo”—not really a “stingray” I shouldn’t think, as the Guthrie translation has it, but rather a specifically electric ray (Torpedo torpedo). His power? To stun, to numb. A glancing contact produces paralysis; one isn’t sure what to say next.

In the second part, however, there is none of that. Instead, Socrates seems immensely adroit at eliciting exactly what he wants in this phase of his teaching-work. He gets a lot of movement and speech out of his pupil.

Which of these is “the Socratic method” still thematized in law school classrooms? The latter, really, I think. The leading by questions. Not the rendering-mute by stupefying techniques of Destruktion. That is pretty uncommon in the professional schools of our time, I should think.

Both of these modes, however, can be understood performatively, and we spent a good deal of time on theatrical/performative readings of several key moments in the text. (Important reference here, which came up in our conversation, Martin Puchner, The Drama of Ideas.)

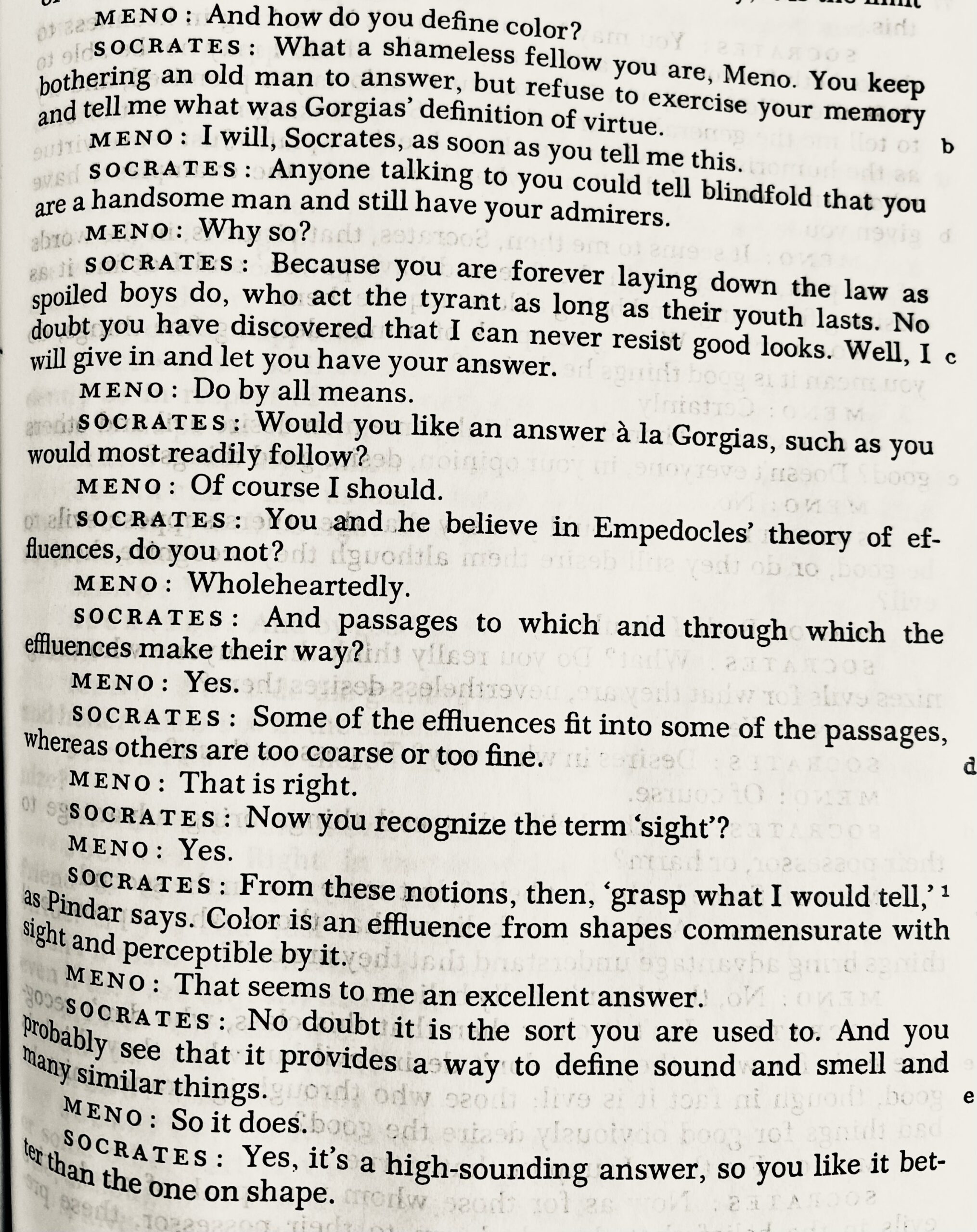

This passage detained us. We noticed that Socrates is here “performing” the kind of philosophical answer that Meno seems to want — in contradistinction to the kind of answer that Socrates has already provided (which doesn’t conform to Meno’s Gorgias-addled sensibility). There is something of the hypnotic in the way Socrates’ interlocutor here, as elsewhere, appears to be slipstreamed into a peculiar zombie-conformity with Socrates’s “script.” (In the final line, some translations actually have “Theatrical” for “high-sounding” — the Greek term, Justin pointed out, is a cognate adjective meaning “tragical” or “of or pertaining to the high style of theater”; there is a whole super-interesting essay on the translation of this word in the Meno that I just found — check it out!).

This hypno-zombifying foo is a feature of both part one and part two of the Meno, and it may have something to do with Meno’s own allusion to Socratic “wizardry” (and it may have more than a little to do with the rage of Anytus and others downstream).

Eros, too, figures here in this passage (at 76a) — and we permitted ourselves a moment of reflection on the libidinal economy of conversation in general, and pedagogical encounters more specifically.

RS suggested (as I understood him) that Socrates seems to come across as a person skilled/adroit in human situations — a person with a feel for what to do in conversation. And this feels really right. It goes to the heart of what obviously made Socrates so compelling to his contemporaries, as well as to the long tradition that inherited their efforts to document what he was “like.”

This made me want to invoke Nietzsche’s damning denunciation of “Socratism” in The Birth of Tragedy. For Nietzsche something of that very “personableness” — that extremely self-possessed, never-discomfited, hail-fellow-well-met energy — is precisely what marked Socrates as the new prophet of soullessness: Socrates was “happy,” because he basically liked the way his feel for things felt. Yes, he went around saying he didn’t know anything, but he seems to have been pretty sure he knew that — and he was cool with it.

What about pain? What about suffering? What about tragedy? Or even just BEAUTY — what about that? Nietzsche didn’t think Socrates had any equipment for that stuff. Indeed, that very incapacity was, in effect, his secret sauce. It’s what made him epochal. For Nietzsche, Socarates marked the birth of intellectual complacency masquerading as “inquiry.” This made him, in Nietzsche’s estimation, something like the patron saint of professors. This was a big ick for the uber-dramatic sage-bard of Sils Maria. From his perspective, neither knowing nor not knowing, thusly modeled, can do us any real good at all when it comes to the stuff that matters most: our existential condition, our existence before death, our status as hostages to time.

By affecting, and perhaps achieving, a blindness to all that, Socrates serves maieutically to engender a newly majestic stultification: cheerful thinking as supernal cluelessness.

(Full disclosure: I am sympathetic to this reading of the figure of Socrates, at least as he comes down to us.) [I’d be curious to hear more, DGB. For me, Nietzsche’s takedown, scathing as it is, lands on a strawman. I think this has to do with the “epochality” he attributes to S. I just don’t recognize much of the Socrates we read in the nineteenth-century German’s “Socratism.” Nietzsche casts Socrates as the grinch of tragedy and brands him as a “despotic logician” (112). Socrates wallpapered the awful truth of existence with the illusionary screen of “scientism” (3). Well, I’m all for pitting “science” against “art,” if that is what we’re doing (4). But why the Hellenic masks? Who was it that said all philosophy is “unconscious autobiography?” Oh, right. Don’t get me wrong. Nobody does brooding better than Nietzsche. But we just saw Socrates educate a slave and humble a tyrant with warmth and wit, no less. Talk about power. I’ll take him over caustic sneers and ecstatic ululations from a pontifical nay-sayer any day. RS]

Back all that out for a second. Ask a different question: What does it even mean to teach when you think everyone already knows everything?

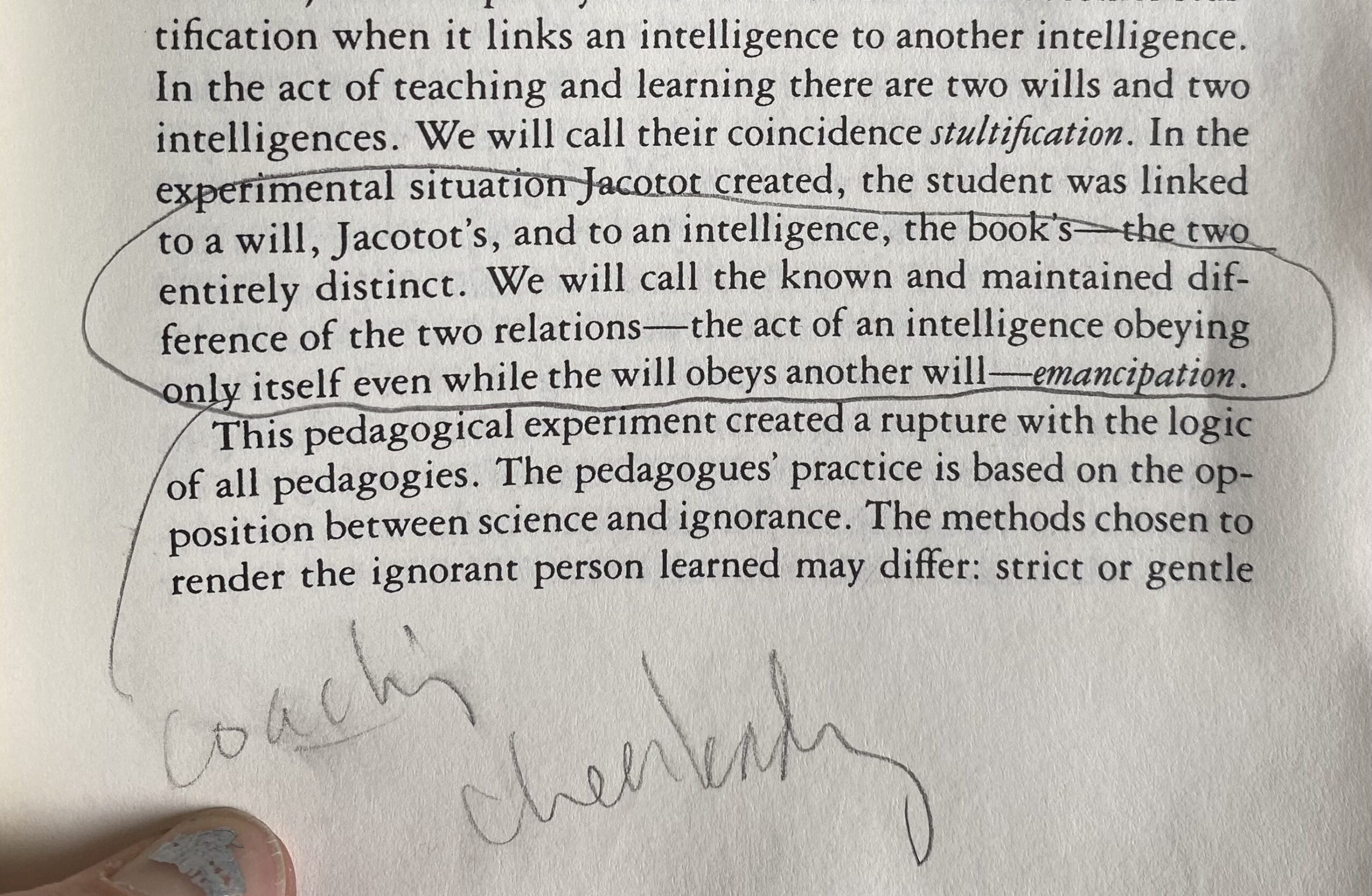

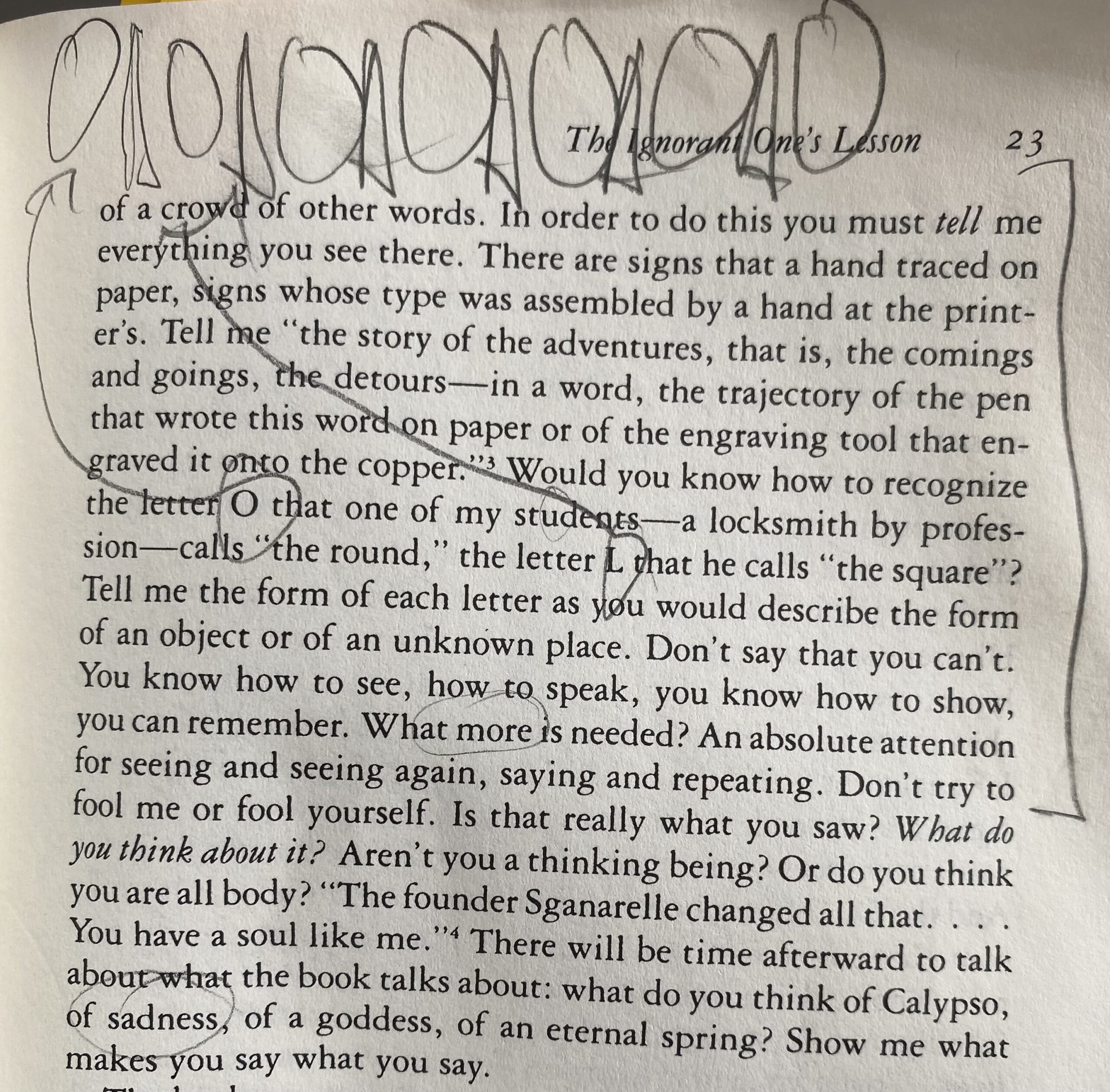

This is, of course, a very deep question. We will see it answered in a manner that stands quite apart from the Meno when we get to Rancière’s The Ignorant Schoolmaster. Teaching in such a way as to demonstrate equality is a very radical project, and while Rancière positions it at the crucial nexus of democratic aspiration, Socrates, at least as figured by Plato, does not seem especially interested in playing out the (potentially democratic) implications of his own theory of knowledge. Certainly The Republic is anything but democratic/liberal — on the contrary, it is basically sort of terrifying. No?

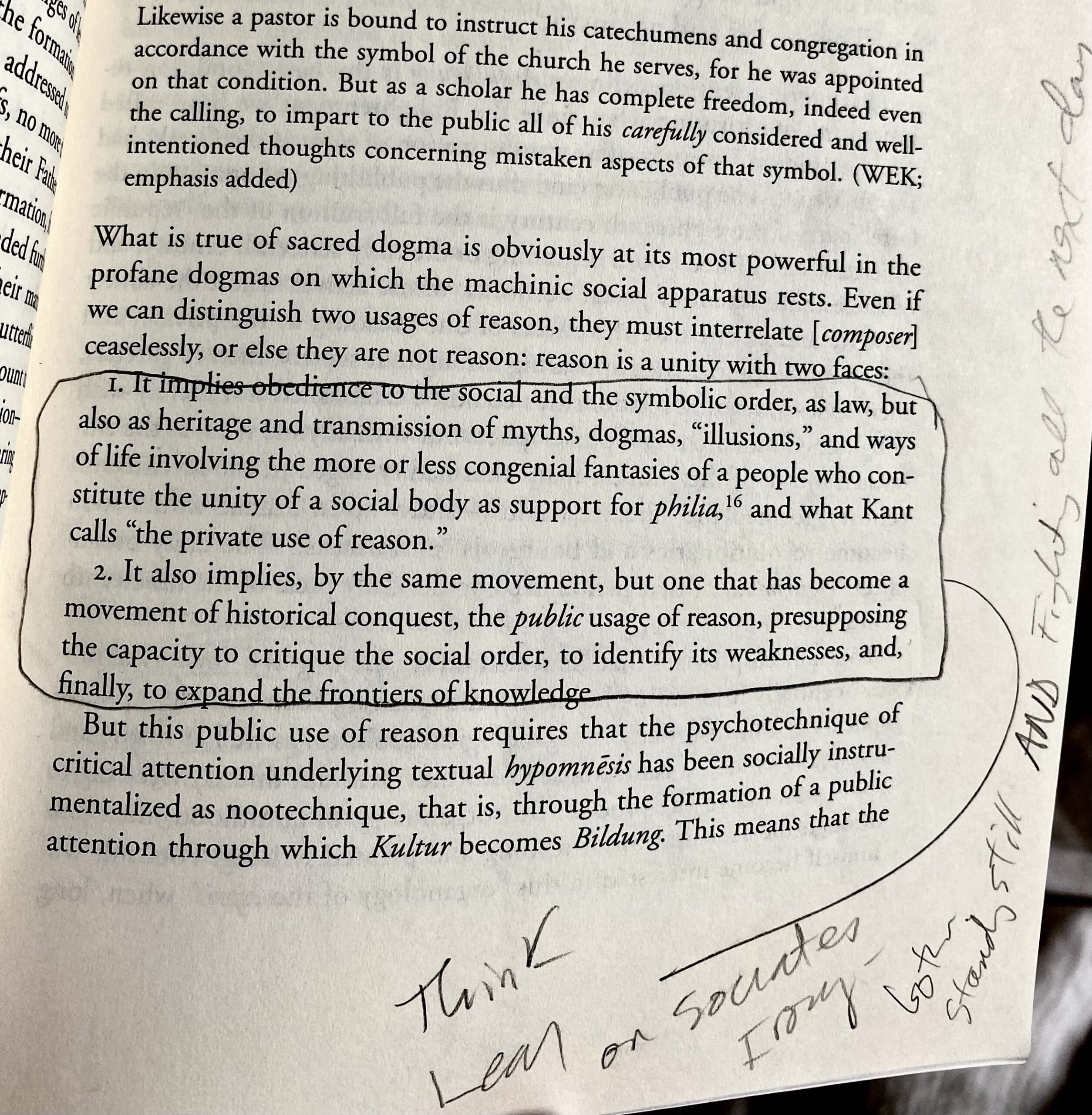

The Noble Lie. We spent only a moment on this. It is such an extraordinary punctum in this canonical text. I referenced it in relation to the Stiegler, in that I believe it is not wrong to understand Steigler as centrally concerned with something like “mytho-facture.” Not that he is a fabulist, or a fantasist, or a proponent of some kind of cheap ideological propaganda. Not at all.

But when he alludes to “nootechnics” I take him to be referring to a stratum of shared commitment that is a layer deeper than “psychotechnics,” which are themselves deeper framing architectures that enable/condition our “primary retentions” (in a Husserelian sense).

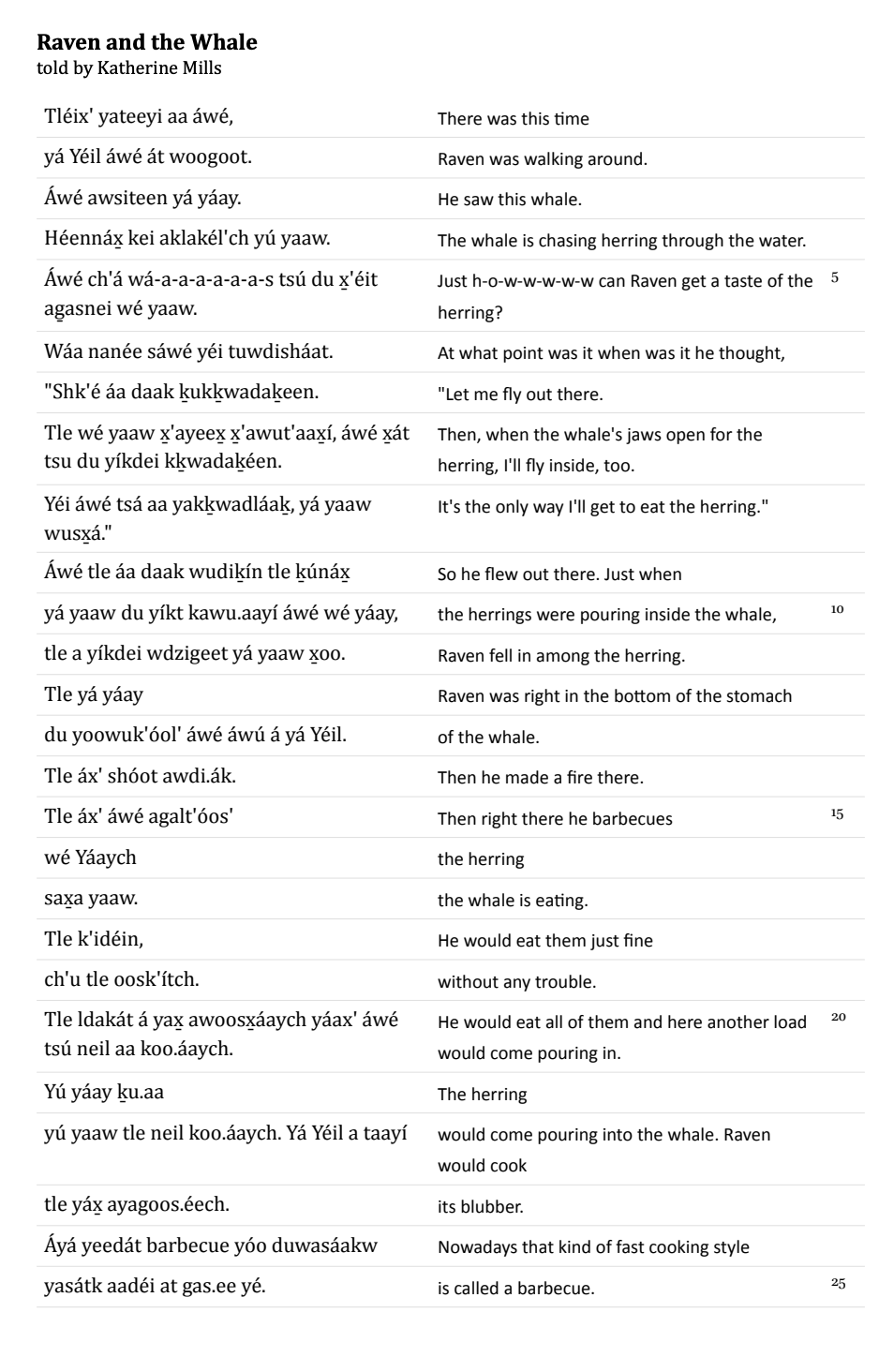

Which is to say, human communities are built out of what they share by way of analytics/narratives that are themselves, functionally, “conditions of possibility” for thinking. These are contingent, emergent, and specific. They are historical. They are, in effect, “tradition.” They therefore stand in some ambivalent relation to what can be dismissively called “myth.” This layer of ourselves, when it is operational, is also a layer we share with others. It does not exactly defy critical scrutiny (one function of “reason” for Stiegler, a true inheritor of enlightenment ideals, is precisely the reflexive and emancipated investigation of such foundations). But we cannot, somehow, “do away with it” and remain human (the other function of reason is exactly to equip us to move from and with what we share). Here is Stiegler on just this (it is the passage I read in our final class exercise/discussion/experiment — see my marginalia about the echo I felt, here, of Lear on Socrates, last week, where we read that meditation on the “twinned-ness” of Socratic ironic distance/alienation [pausing all day to think] and Socratic civic commitment [fighting courageously like a good athenian]):

Part of what is so puzzling (fascinating, really) about Socrates’ theory of knowledge is the strange way it underscores and erases “history” all at once: on the one hand, everybody already knows everything because their souls are eternal, and therefore everyone has already come to understand everything across countless lives (learning is thus merely a matter of remembering); on the other hand, however, actual history is totally irrelevant, and indeed utterly undifferentiated (because everyone already knows everything, and all they need to do is remember it). The kinds of truths that are of interest here — Justin made this point — are not “bodies of knowledge” (they have no particularity, they cannot be located in time or space), they are, rather, eternal things, unchanging things, truths like those in geometry and logic.

*

I have already written a lot, so I am going to skip briskly through some of the rest of the stuff that was on my mind during our time. But I would be remiss if I omitted to mention the intensity of my reaction to the Isocrates. It was not a text I knew well before Jeff suggested it, and I really felt how beautifully it fit together with our other reading. The lovely chiasmus of this “apology” against Socrates’s own: both condemned for “corrupting the youth,” and one invoking philosophy as the anti-rhetorical, while the other invokes rhetoric as the “true” philosophy. Very beautiful, somehow. And affecting to think of the different outcomes.

For my part, in the space of politics, I am more sympathetic to Isocrates’s invocation of “public reason,” and the essentially civic/discursive work of persuasion. One can hardly think of a more “rhetorical” move than saying “my way of getting to the truth is 100% rhetoric-free!” and something about that aspect of the Socratic-philosophical program creeps me out. As a historian of science, I have long been especially interested in the forms of truth-making that have succeeded, maximally, in presenting themselves (successfully) as “just” the truth-stuff, with none of the human-stuff. This is sort of how science works. And it is powerful magic. And by no means trivial. Nor is it all some kind of “ruse.” But its modes do not conduce, in my view, to successful orchestration of social life in which humans flourish in their non-inhumanity, and do so well with other beings. The reasons for this should be obvious: it is an “inhuman” project, so it deals imperfectly with humans.

So give me Isocrates any day over Socrates, if the project is organizing a polis. Proto-pragmatism? I can see it…

CA note: “Concepts are more like a beating heart that reoxygenates the blood provided it is connected to the rest of the circulatory system.”

Bruno Latour, The five loops of the circulatory system of science (1999).

*

Ok. For the last thirty-five minutes we sat cross-legged in a circle on the floor and tried to do something along the lines of a “consciousness-raising” exercise — with “taking care of the youth” as the theme. It only sort of worked, maybe. Or even maybe didn’t work. Why not? Hard to say. But it was interesting to change our body positions, and reconfigure ourselves in the room.

And as for the Stiegler itself, I will say only that I do subscribe to the idea that education itself can be understood as the formation of attentional capacities. Some of you may know that I have given a lot of the last decade to work in this area (I am very actively involved with this non-profit activist coalition, called The Friends of Attention, that works in that area, and did this book last year).

Oh, and while we are on links. Here is a link to the gig-of-old: Jeff Dolven as the Socratic figure “Caspar Tootles” in a redux performance of the Symposium.

[mischievous winking emoji]

-DGB

*

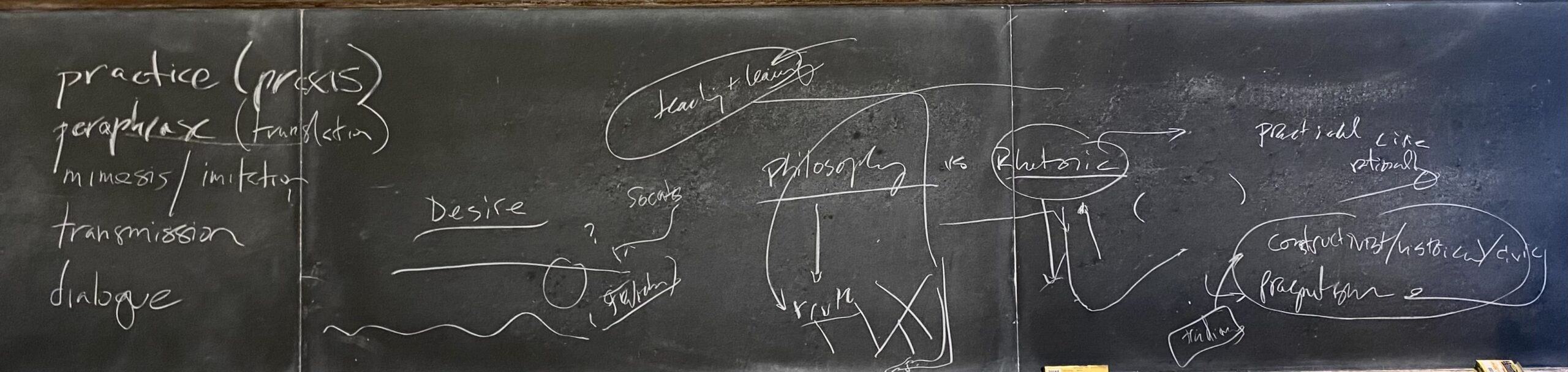

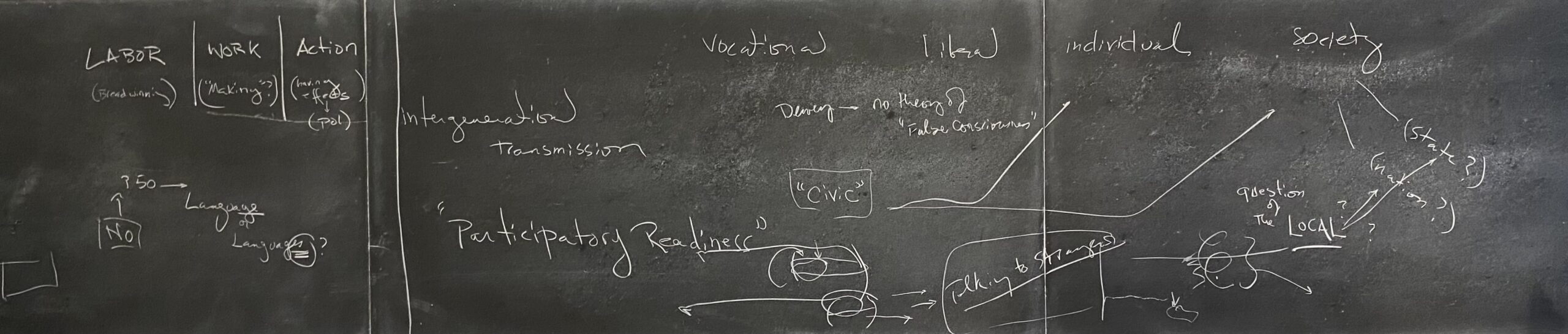

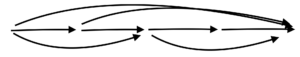

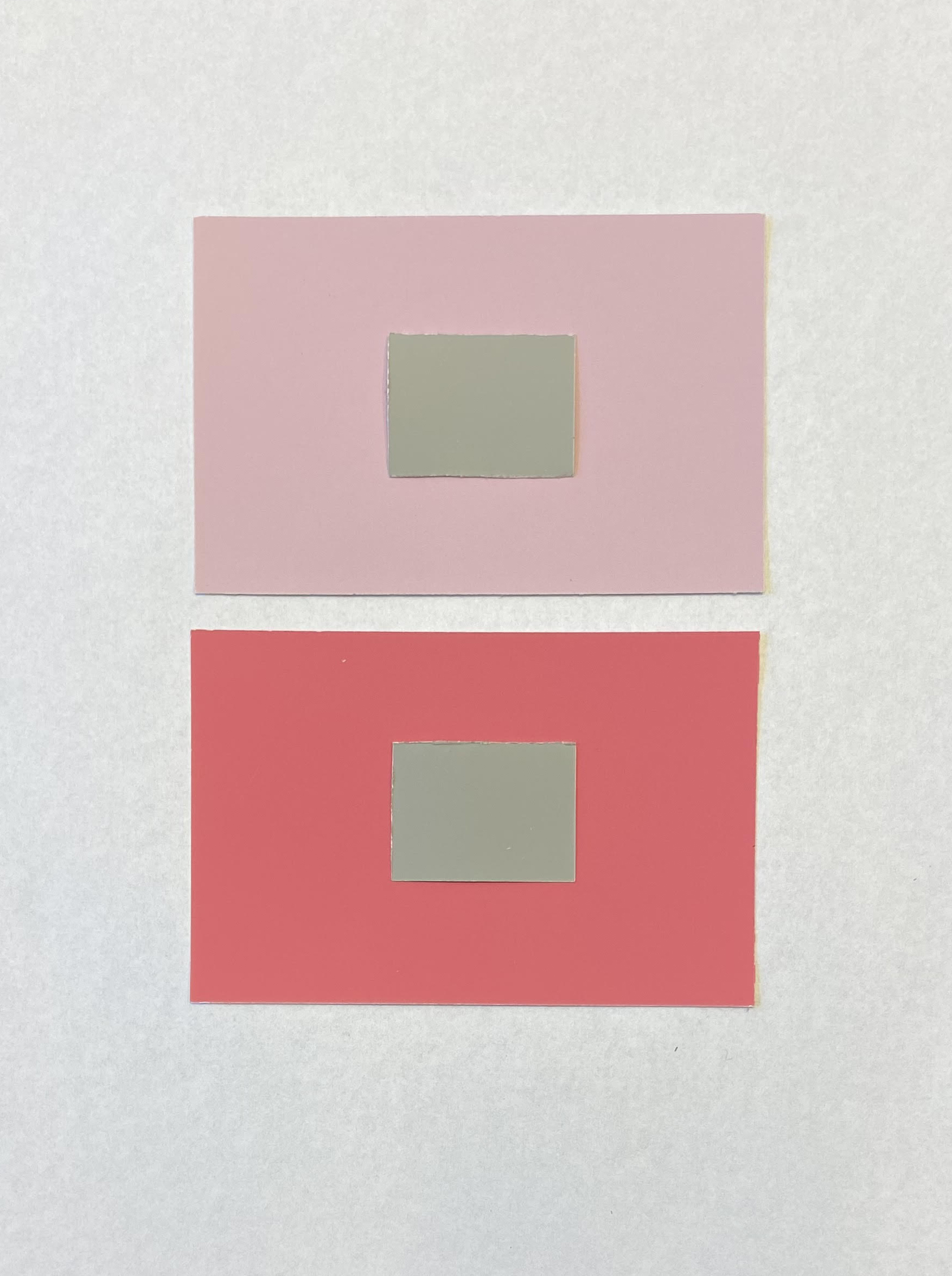

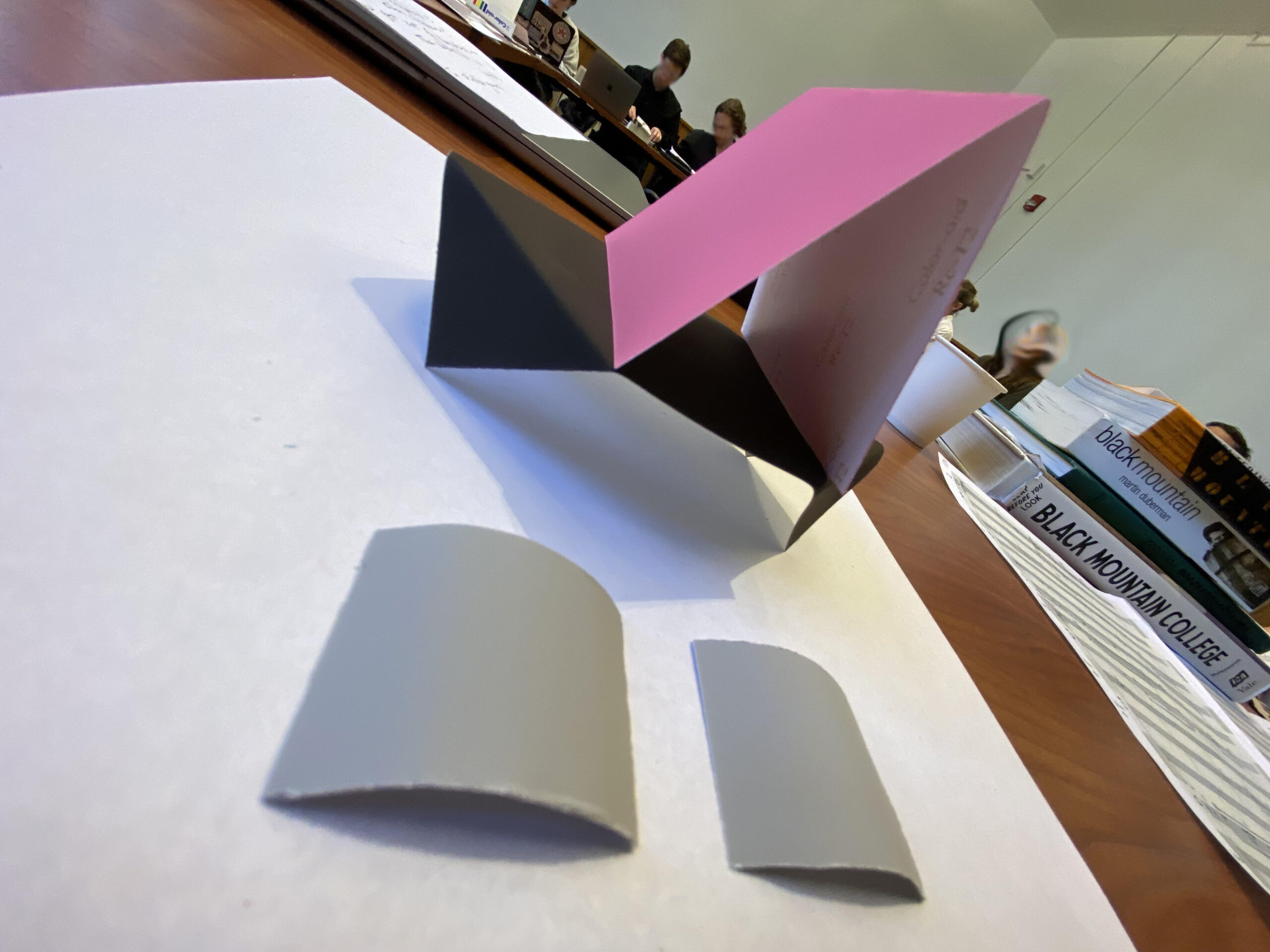

I’m going to start with some high-altitude thoughts about the readings—a map I made in my head on Wednesday morning, which, inevitably, we did not follow, but may be worth laying out for you now. Or maybe not a map, but a series of sketches. Let’s start with Plato, and the elenchus, particularly as we encounter it in the Meno and the Protagoras.

This one you probably have to imagine in three dimensions, because each turn is also supposed to be an advance in the conversation; so, a spiral staircase, headed up. Or, headed down?—if its fundamental work is critical, dismantling opinion. Or then again, maybe it’s just spinning in place, and the effect is dizziness, or perplexity. At all events: here is the idea that teaching is closely entailed exchange between two parties. You might lengthen one or the other of the lines to suggest the predominance of one or the other of the speakers. There are power effects here, as Lauren observed. But let the diagram stand for the moment as at least an idealization of dialogue.

Next, Isocrates:

This one is simple enough: Isocrates is a rhetorician who performs in public, and his speech goes one way. This is what Socrates so distrusts, the continuous utterance that is never accountable to itself or to its audience. It flows on, untested. Isocrates clearly does believe that the polis can benefit from such speech. That said, as a diagram of his pedagogy, it implies more than it shows, for what he is defending is training in rhetoric, which is a matter of exercise, effort, practice; and typically, of the analysis of speech into its component schemes and tropes, to facilitate that practice. Education is training to speak in public. Also, to some extent, theater?—another term that Socrates abjures.

Now how about this?

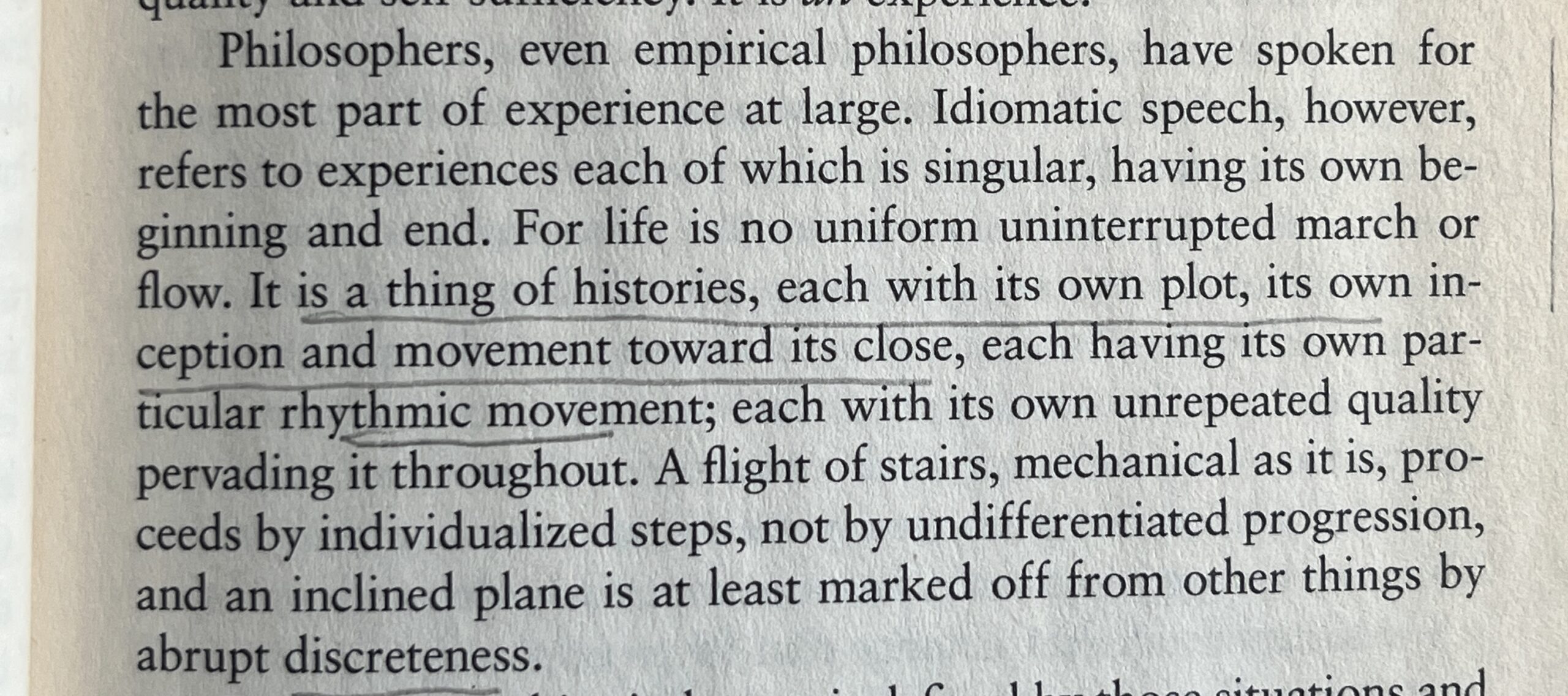

What a hopeless project, a diagram of Stiegler! But what I am attempting to capture are the long circuits of human experience that for him are both the work of education and the quality of attention. I find the argument challenging, but hugely stimulating: the idea seems to be that when the young study with the old, they internalize old and deep, even mythic patterns of thought that undergird the specific lessons we think we are teaching; we may not be conscious of these patterns (“tertiary retentions”), but they are nonetheless available to imitation. [Maybe I’m digging into the question of “transgenerational learning” too literally here, but this did make me wonder – is there a school that takes this into consideration in a meaningful way? This feels like one of the great losses of the learning-as-career-making model – that the only intergeneration exchange happening in a typical classroom is two pronged, split between the teacher (almost always older), and the students (typically of a similar age). While there are important exceptions to this rule, I can’t think of a school that meaningfully considers age as part of the makeup of the diversity of experiences that constitute a meaningful learning environment (maybe something like Columbia’s School of General Studies, for ‘non-traditional’ degree candidates?). While intergenerational learning is happening at some MFA programs (though not, it seems, necessarily by design), I can’t think of any humanities oriented degrees that support “learning” as such beyond in a transgenerational setting that doesn’t ultimately amount to job training. But maybe a school is the wrong place for this kind of learning entirely? – CB] Attention itself is not measured by time spent in concentration on a given object, but rather, by the thickness of the encounter, the ways in which a given act of reading (for example) activates associations that are transgenerational. [I really care about this part of this text, and love what you are doing with it here, Jeff; I have inserted a longish comment on this part of Stiegler here, which is also a gloss on Dolven’s analysis -DGB] [[I’m trying to take in what’s being said… taking note of Steigler’s singularity of attention. So, we have one attention to give at one time. Riffing on DGB’s physics invocation with “scintillates”, like a laser, this attention can ‘ping’ and excite an entity. The depth of attention depends on the amplitude of excitation, which may resonate and excite other layers in the “circuit” (or we can call them subdominant modes). Decoupling the depth or amplitude of attention from a linear marching timescale in this way … is liberating? With the attention we pay, time is not money. Does this singularity of attention imply that learning is necessarily discrete and diachronous (referencing back to JD’s note earlier note), like the stitches in Stiegler’s knitted textile? Idk, because, like, Voldemort splits his soul into seven pieces, can we divide our attention into multiple, synchronous parts and expect to end up somewhere good? Do hypnotists deal in this type of magic? Asking for a friend. -LD ]] [[[Hey — just quick to say: I love to read LD digging in on this metaphor; I am not sure Stiegler himself thought it in ways that were especially concerned with the fine-grained elaboration of the “vehicle” in quite this way, but I DO think the proposal holds up under such scrutiny. It could be a very cool project to play it out a few ways along the lines you explore here. -DGB]]]. Quite odd!—given that we usually think of attention as a perfectly circumscribed subject-object situation. But it’s worth trying to get your head around, this proposal that to attend to an object is to activate these associations/affinities/contests etc. Which would be to say that attention is a meaningful condition, not just a perceptual one, and that the more meaning there is, the more attention there is. I think that’s right? So the diagram suggests long circuits across four generations, and you might think of an act of attention as happening anywhere along that range, cutting across two, three, or four lines of transmission. So what, you might ask, is the implicit pedagogy here? Play is one example for S., especially with a Winnicottian transitional object. (This is in keeping with his organology, which is to say, his sense that human organs and various technical prostheses are to be considered together as part of the larger project of nootechnics; another really hard idea, but he wants us to wean ourselves from categorical distinctions between, say, the hippocampus and the Aeneid and the internet.) Another vital scene of instruction, for him, is reading itself. Play with a book?

The last one is simple:

You could, of course, prefer an architectural model for the pedagogy of Womanhouse, a house of many rooms, some of which are stages. But the circle is the basic arrangement of consciousness raising at it was practiced around 1971, going around, with everyone speaking about a common topic. It’s quite different again from any of the foregoing. There is opportunity for testing, for debate, of Socratic sort—but it is not built for that, because there is no necessary argumentative link between any two positions on the circle. It seems to be optimized for an accumulation of ideas and experience, on the assumption that the participants will learn that way, responding to one another, to be sure, but in a more holistic way, with less emphasis on testing the ideas of any one member. It seems to be the group that is learning. And what an open word “consciousness” is! There’s probably another affinity with analysis or group therapy, and there, maybe a connection to the Socratic scene in the sense that the activity is arguably critical—not because it undertakes specific refutations or unveilings, but because such talk in a supportive environment about charged topics (sex, gender, labor!) will surface ideological assumptions, raise them up where they can be seen.

CA note: How can a democracy deal with questions of affect and time, with pre-dividual networks and virtual threats? “While the social nervous system may be stimulated to react to the uncertain threat of a (place something here), somehow the same elements work in reverse with a crisis like (place something here), in response to which our sense of emergency towards a virtually certain disaster is dulled. The dispersion of the threat into a surround of fear seems to make it inescapable, while the same dispersion around (place something here), the difficulty perceiving it as an object or event, allows a perpetual deferral of action. This suggests the need for a theory of democracy which can account for affect in more complex ways; we ignore them at our peril.”

And,

Tony Cokes, Evil.12. (edit.b): Fear, Spectra & Fake Emotions (2009): https://vimeo.com/250387442

So: back-and-forth, broadcast (and the training for it), long circuits, the circle. All schematic models of a pedagogy that might define a school, or be included in it. I mentioned John Durham Peters in class, and you can read what he has to say about dialogue and broadcast in Speaking into the Air. And I should also say, this kind of diagram-making is an old habit of mine, as you can see in the rest of that chapter from Scenes of Instruction that Graham cited last week.

OK: so we might have made the class a geometry lesson, if my whimsy had played out: what did happen? We were launched with two wonderful thought pieces, for which thanks to NB and RS. I’ll just ramble around our conversation a bit. The Meno and the Protagoras are both centrally concerned with the question of whether virtue is knowledge or not, and also whether it is many or one. You might be able to argue that these are versions of the same question: that is, if there are many virtues, none reducible to the other, then you have yourself a taxonomy, which you can memorize, repeat, and so on. If virtue is only one thing, it seems less knowledge-like, and it becomes difficult to distinguish between two versions of coming to a conclusion, 1) an essence or 2) an aporia. I’m getting dangerously close to trying to do philosophy here, though, and so let’s stick to pedagogy, which is where our discussion was. (Except that in these dialogues, are philosophy and pedagogy properly distinguished?—and that is not true of all philosophy.)

I feel like we didn’t quite get to how dialogue is really supposed to teach you. We should keep thinking about that. But we were very attentive to possible deflections. One was theater, which seemed to be, from Socrates’ perspective, the performance of knowledge you already have (see the passage DGB cites), particularly as a continuous, uninterrogated utterance. [Shameless plug here: I co-taught a course a few years back on theater and teaching — it was called “The Enacted Thought,” and I think I showed you all the thick discussion thread that came out of it (we did a performance together as the final project, and it travelled to a theater festival in Europe) – DGB] Mere theater, that is, with all the ancient prejudices about its seductiveness and inauthenticity. To perform a thought in this way, for Socrates, is not to know it, but merely to hold it as an opinion, effectively, a script you read from. On the other hand, there was a really interesting line of discussion about the theatricality of the dialogue form itself, with its multiple characters, its currents of affect, its obdurate im-personation of even the most abstract reasoning. Why, why? To remind us that reasoning is never unsituated? To model for us how dialectic can be pursued even in the variable weather of human conversation? Is all this human stuff interference, and Socrates has to teach through it, if teaching is what he is doing? Or is this all somehow part of the teaching?

There is also the deflection of desire (that is, desire as deflection, from dialectic), the various flatteries and half-seductions that arise, and here we might ask some similar questions. Is this how to teach—part of the art of manipulation that holds open a space for dialectical rigor? Or is it somehow part of the lesson? (Elsewhere, of course—especially in The Symposium—desire will be the ladder up which knowledge must climb, or the lower rungs of it, at least.) One thing that desire did was make us aware of power, and the potential for forms of domination in such exchanges, especially when they are so asymmetrical. One way to abjure power relations is to defer to method, inquiry, etc., but these dialogues are interested profoundly in the techniques of personal manipulation—they have often been read as celebrations of Socrates’ thought, but none of the difficulty we experience in reading them that way is extrinsic or accidental.

And that torpedo fish, yes yes!—a lot here finally turns on how we value that condition of numbness. Is it a way of starting over, resetting; a kind of remedy to our complicities, an opportunity to re-found our knowledge? Or at least, see it fresh? (Is it like being grabbed or shaken by radical irony, for Lear?) But funny to think of that as being numb. Numbness seems like the opposite of ecstasy. Is it? Quite remarkable to think of education as directed toward this state of paralysis. Again, an interruption of education, or the only moment that could truly be called education? I don’t think Stiegler thinks this way, with his emphasis on long circuits. Is Socrates a circuit breaker? (I suppose I should say I’m also really interested in perplexity generally: often the difference between people who are comfortable in school and people who are not has to do with how comfortable they are being perplexed. If you expect to know the answer right away, if you assume that the teacher is the teacher and the smart kids are smart because they somehow already get it, you are going to feel awful a lot of the time. But if you think of puzzlement—DGB might return us to the phrase “negative capability”; is that anything like numbness?—as full of potential, as fertile, as propaedeutic rather than terminal, and as everybody’s predicament and privilege—well then, you might come to be quite happy in school; at least, if your school is one that gives you time to be perplexed.) [“Negative capability” is an odd phrase. It seems to describe tolerance for ambiguity. That might fuel the latent abundance JD invokes. But it performs its own kind of ambiguity when we think about its origin. Apparently, it was coined by the poet John Keats in a letter discussing Shakespeare. The Bard beats other poets like Coleridge, Keats says, because he’s untroubled by “any irritable reaching after fact and reason” when faced with “uncertainties, mysteries, doubts” baked into human existence. Knowledge-hungry poets like Coleridge, on the other hand, are “incapable of being content with half-truths.” I get that Romantic poets and friends of poetry probably think this hits the mark. How else to perceive the identity of beauty and truth than by suspending that pesky drive to be logically precise. But do we really want to sacrifice fact and reason on the altar of poetic truth? Is the beauty-truth really “all ye need to know?” Take “negative capability” from aesthetics and put into politics and you might get something like the cognitive dissonance, with all its pseudo-justifications, that we see so much of today. RS]

OK: to the break! And then back. Consider that circle a first experiment in something it would be great to get comfortable with and good at, fitting ourselves into a new pedagogy, in this case the discussion-circle of consciousness raising. I took my little description from Priscilla English’s “Womanhouse: A Feminist Creative Environment,” which she wrote in 1972. She quotes Judy Chicago: “We started having consciousness raising sessions during which everyone sits in a circle and speaks individually on a single topic—your relationship to your mother, anger, sex, whatever. Soon patterns begin to appear, not patterns of personal neurosis but of the culture’s dogmas regarding women. This gave us a lot of material to build art from…” (2). I gave a general description above, but it’s worth observing that Chicago is especially interested in the way that a group can discover how thoughts experienced as personal neuroses can be recognized as a culture’s dogmas—or one might say, as ideology. Quite a different way of surfacing ideas from dialogue (or even for the group-Socratism of Habermasian speech situations?—that’s a tendentious characterization, not sure I would sign of on it, but I’d like to think more).

Anyway—a little bonkers to think of consciousness raising as a way of coming to grips with (is that the metaphor?) Stiegler. But we’ll have to see what we can make of the misfits as well as the good fits. If bonkers, why? Certainly it is not a good mechanism for the canonical pedagogical activity of paraphrase, not in any order, anyhow, that would track the argumentative progress of the text itself. What did we get instead? Quotations, which could resonate; the shorter the better, maybe, in that space? (“Intelligence is taking care,” is that right?—that was raised up for me by hearing it together as a group.) A little bit of paraphrase. A couple of moments of testimony to the experience of reading the book, its difficulty, its language, and so on. A few key ideas surfaced, about long circuits and short circuits of attention. I don’t think any of us stood up feeling like we could do a better job of putting the arguments of those opening chapters in our own words. But it’s an interesting thing: If I could do that on Wednesday afternoon, and could do it Thursday morning, I would probably do it a little less well (less thoroughly?) next week, next month, next year. For most of us, such arguments are hard to hold in the head, at least without refreshing. But were there moments from that circle that will linger in mind? Even, more than a satisfying passage of group-exegesis might have done? I speak as a real devotee of that latter project. It’s possible, if we had more practice with the circle, that we could use it better together to surface the sorts of patterns that Chicago et al. found in their sessions.

I was going to be shorter this time. I’ve been longer. Forgive me. One final thought. We’re in an unusually reflexive environment, all semester: what is teaching? What is learning? Is it this? (Pointing to a text.) Is it this? (Pointing to—the room? Someone else? All of us?) That’s a little weird for me. But in a good way! For it to really work, we’re going to have to manage a week-by-week balance between digging in and standing back, inhabiting the form of pedagogy we find ourselves in (there will be moments when it will be pretty traditional I expect!—and other moments when it’s not), getting the most out of it, and also stepping away. There were a few moments in the last class when we were all at the edge of the pool—I just want to say, let’s jump in! That jump might take the form of questioning the question, or redirecting it, as (or more) usefully as answering it. It’s all interesting for us. I’m really looking forward to next Wednesday.

-CT, er, JD

[We were unfortunitly unable to truly speak about “womanhouse” at the end of class. I Brought up Phyllis Birkby and her architectural work in class so I wanted to insert some of it here for any one interested. Id also recommend checking out “The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality, and the Politics of Domesticity after World War II” by Stephen Vider which mentions Birkbys work on queer living. -CF]

* * *

CLASS 3

Readings

John Locke, Some Thoughts Concerning Education and Of the Conduct of the Understanding, eds. Ruth W. Grant and Nathan Tarcov (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 1996), §31-99 and §147-216 from Some Thoughts Concerning Education, and §1-7 from Of the Conduct of the Understanding .

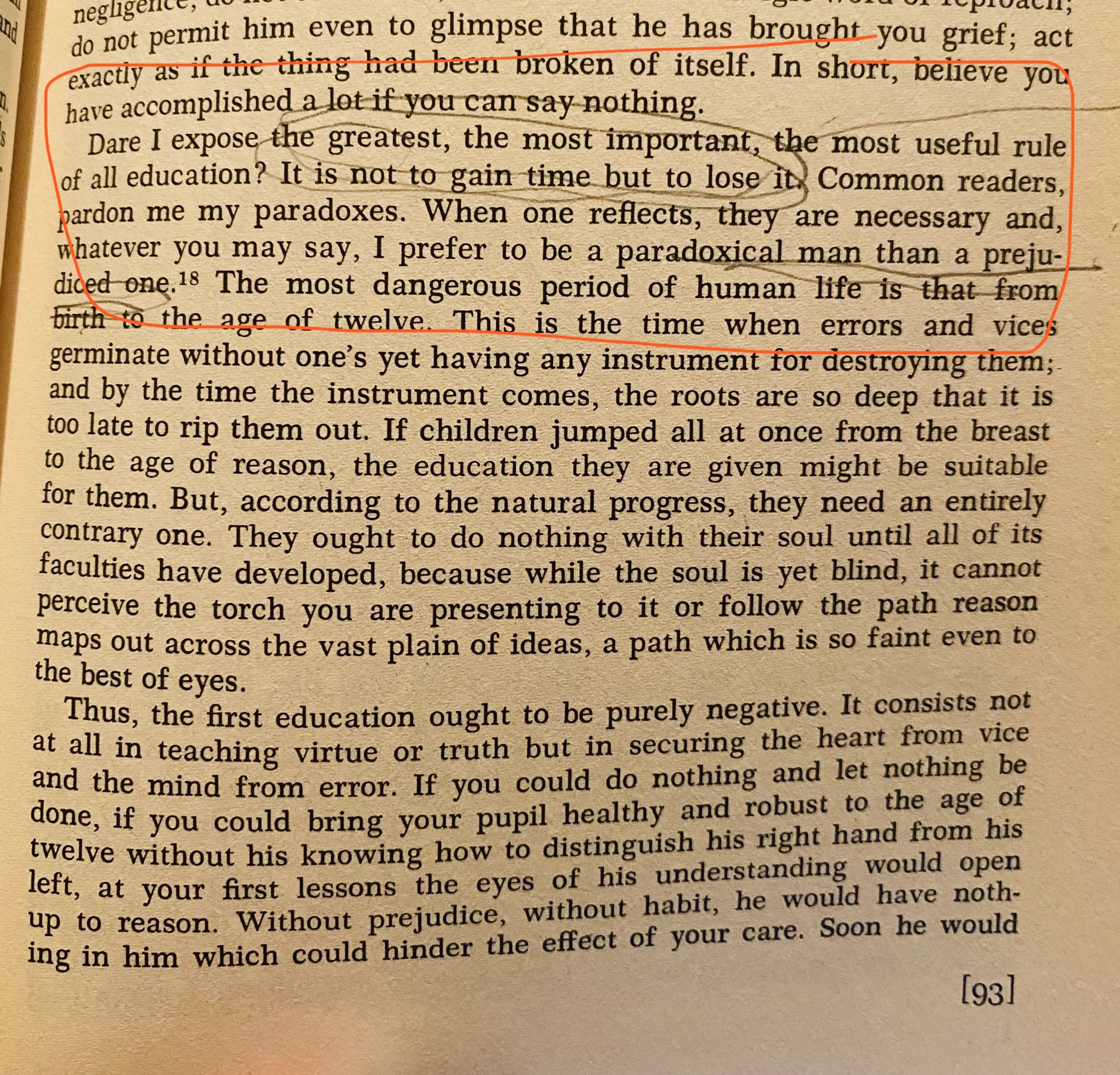

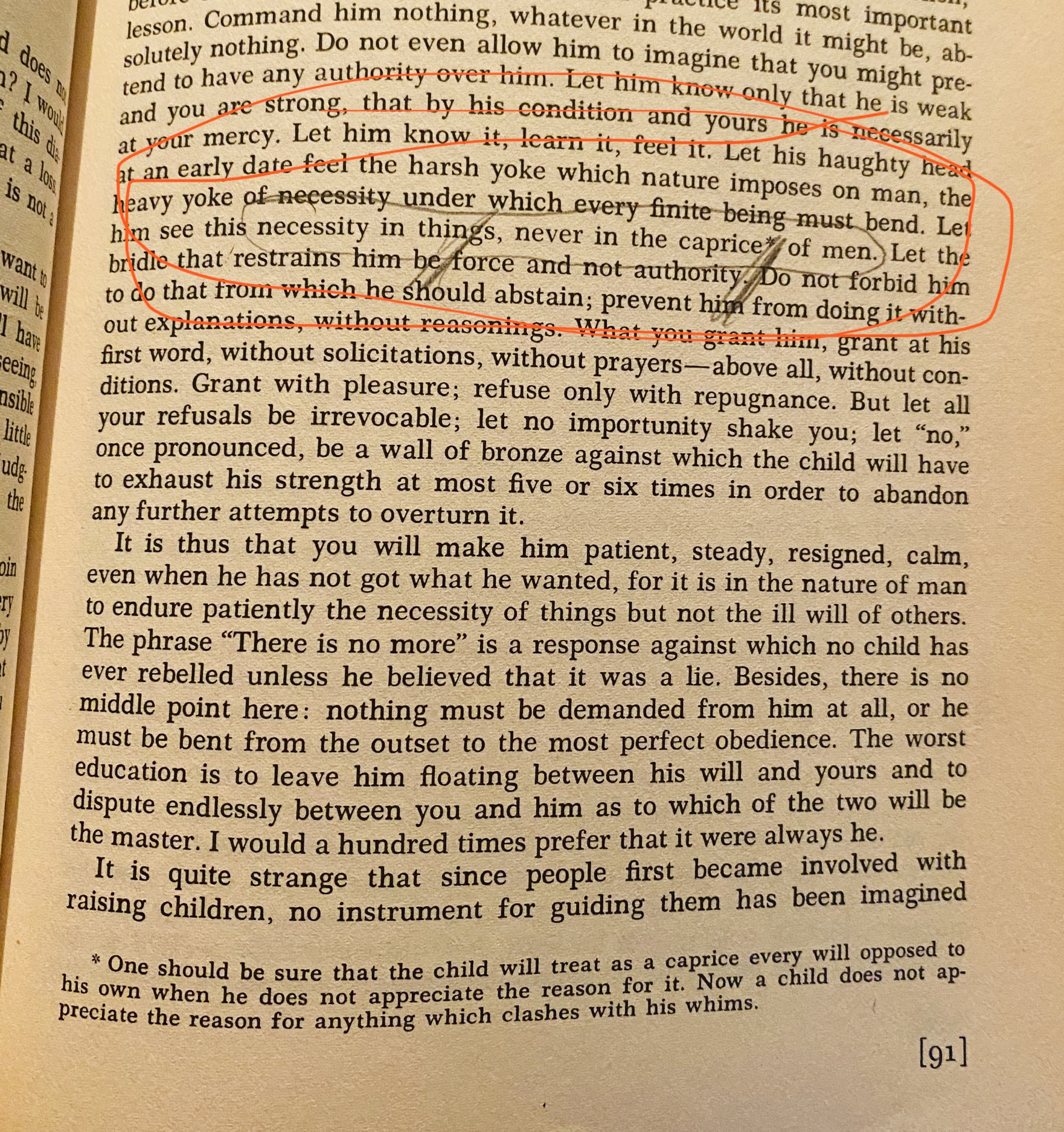

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Emile , tr. Allan Bloom (New York : Basic Books, 1979), Books I and II ( pp. 37-164) and part of Book IV ( pp. 211-257).

Julie L. Davis, Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), focus on chapters 1-4.

Two short texts from Outer Coast (to set up our visitor this week, Matthew Spellberg, dean of that institution, which you can read more on here): 1) their Motto; 2) their Land Acknowledgment.

OPENING THINK PIECES

Last week we spent some time thinking about Socrates’s theory of knowledge—as DGB posed it in his post-seminar reflection, What does it even mean to teach when you think everyone already knows everything? John Locke’s Some Thoughts Concerning Education gives us an opportunity to ask the converse: What does it mean to teach when you think everybody starts out knowing nothing at all? What does a complete education look like if the human mind is a perfect tabula rasa? Locke answers that question with a far-ranging set of prescriptions (and proscriptions, too) for the liberal education of young gentlemen, stretching from the cradle to the altar and touching all phases of early childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. Virtue and its inculcation is one of the principal concerns of Locke’s treatise, giving us another lens onto one of the central questions of the Socratic dialogues, which motivated our discussion last week: what is virtue and can it be taught?

Locke doesn’t deny that different people come into the world with different aptitudes and capacities—differences we might call innate or genetic—but he ascribes to education a far greater role in development. As such, he is unequivocal on the question of whether or not virtue can be taught: it can. When a person lacks virtue, Locke sees a failure of education, not a foregone conclusion determined by immutable constitution (here we might think of the examples of unvirtuous sons of virtuous fathers which Plato’s Socrates invokes to demonstrate the opposite claim—for Locke, those sons weren’t destined to be bad, they just needed better tutors). The point to which Locke returns most often and most insistently in Thoughts Concerning Education is the importance, above all else, of a virtuous teacher who can model virtue and instill it in his pupils.

Modeling is key here; as Locke writes, “Children (nay, and men too) do most by example. We are all a sort of chameleons that still take a tincture from things near us….” (44–5) Learning for Locke is in large part a matter of imitation, and for this reason he regards it as critical for parents to surround their children with suitable exemplars of virtue and to protect them against contact with the unvirtuous. [Chameleons here, dogs in LD’s post below, squirrels back in week 1, torpedo fish in week 2 – wondering how/why certain other animals help us think about the capacities/deficiencies of the human animal as regards learning. New Schools, an epistemological zoo? – RS] [[Oh! Interesting proposal, but I have to admit that thinking with/through animals could also be dangerous as it could easily imply a projection of anthropomorphism. Lorraine Daston reminds us that, “The language of perspective carries with it weighty assumptions about what it means to understand other minds. Within the model of a world divided up into the objective and the subjective, and armed with the method of sympathetic projection, understanding another mind could only mean seeing with another’s eyes (or smelling with another’s nose or hearing with another’s sonar, depending on the species)—“put yourself in his place,” as Lloyd Morgan titled one of his chapters.63 Understanding in the perspectival mode implied experience, and individualized experience at that. Here I can only hint at the several intellectual and cultural shifts that created the perspectival mode: the habits of interior observation cultivated by certain forms of piety; the increasingly refined language of individual subjectivity developed in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century novel; the equation drawn between sensory experience and self by sensationalist psychology; political and economic individualism; the cult of sympathy, which expanded to embrace first children, then animals, and finally denizens of other times and places. Whatever the historical forces that forged it, the perspectival mode was most decidedly a creature of history. It is not simply another form of subjectivity; it is the apotheosis of subjectivity as the essence of mind.”

With this said, I think that it’s not only to think from the perspective of an animal, instead of engaging proactively with other forms of knowledge. There are really interesting projects working on reimagining and opening Natural History by introducing other types of knowledge such as Indigenous Knowledges and vernacular ones. Understanding the world in different ways implies to proactively engage with this type of knowledge. It is to care for them, and from there maybe we could start to speak about thinking from the perspective of the other. It requires action and movement. I think that nowadays there is kind of a tendency or a trend (sometimes without the real engagement with the proposal) to say, thinking from a non-human perspective, which at some point should be revised as it reflects on the real power of the proposition. Which I believe is certain and powerful. But, I also think that it requires engagement, reflection, and dedication. I would recommend reading Batsheba Demuth’s Floating Coast: An Environment History of the Bering Strait.-TU]]

(Locke repeatedly uses the language of contagion to describe the corrupting influence of the ill-bred on the impressionable young gentleman, with particular revulsion reserved for servants—the class implications there are discomfiting to say the least.) This is why Locke considers tutoring the ideal mode of education for a young gentleman; he has the best chance of becoming virtuous if he is exposed principally to the example of a virtuous tutor and shielded from the sort of corrupting influences he might encounter at a grammar school.

[On the topic of ‘example,’ Locke reminds us that children are profoundly influenced by the company they keep. In the context of an education, this company is rarely the choice of the child. Through his reflections on the impact of the relationship between parent and child (and later, tutor and child) on a child’s development, Locke insists that the difference between a good education and a bad one (perhaps, then, a good adult and a bad one) hinges on the presence of the right teacher. As AK mentioned, this presence is important enough that if possible, an education received at home may be the only way to prevent the potential for encountering damaging influences. Although Locke’s argument does not anticipate the extent of this damage, perhaps it gives us one possible lens through which to view the impact of the extreme familial distance enforced by the boarding school movement described in the Davis piece. -EH] [[Interesting point… – DGB]]

[[[CA note: I’ve been thinking a lot since reading Locke about the hobbyhorse. I was introduced to the idea by Simon Schaffer when working with him last year. In one sense, the hobbyhorse is a tool or machine to exercise the mind and body. A device of recursion. Some see the hobbyhorse as a substitute for the body itself. But in another sense, the hobbyhorse is also a mechanism of entropy. Whatever your hobbyhorse is can drive you into a delusion, or even a kind of madness, heating you up more with every encounter. Disguised as a play-thing, the hobbyhorse is also a weapon. Is the endeavor for virtue a hobbyhorse? A ‘prolonged practice of bodily discipline’ as described below, it would seem that virtue is a carriage that works the mind but never arrives at any finite destination.]]] [[[[we don’t have a color for fourth-degree comments — so here, I just invented one; but wanted to insert a link to this canonical meditation on hobbyhorses, which launched a line of comment in the philosophy of aesthetics – DGB]]]] [[[[[I have to admit this was my first read of the Gombrich, and—wow! I loved this essay. I cackled at “The ‘origin of art’ has ceased to be a popular topic. But the origin of the hobby horse may be a permitted subject for speculation.” (E.H. Gombrich, “Meditations on a Hobby Horse,” 5) I’m very much of the opinion that totalizing theories of the origins of art are doomed to be beautiful failures at best but are enormously interesting for what they can tell us about the horizons of possibility for art-making in their present.

I found Gombrich’s notion that substitution, rather than representation, was the originary impulse behind the symbolizing and form-giving activities we’ve come to call art a really productive lens onto theories of projection and the transitional object in psychoanalytic theory. Gombrich proposes that the most basic impulse toward symbolic representation originates in early childhood object-relations, when “The child will reject a perfectly naturalistic doll in favor of a monstrously ‘abstract’ dummy which is ‘cuddly’. It may even dispose of ‘form’ altogether and take to a blanket or an eiderdown as its favorite ‘comforter’—a substitute on which to bestow its love.” (Gombrich, 4)

I’m reminded of the passage from Donald Winnicott’s Playing and Reality that Stiegler quotes in Taking Care of Youth and the Generations: “Transitional objects and transitional phenomena belong to the realm of illusion which is at the basis of initiation of experience. This early stage in development is made possible by the mother’s special capacity for adapting to the needs of her infant, thus allowing the infant the illusion that what he or she creates really exists.

This intermediate area of experience, unchallenged in respect of its belonging or external (shared) reality, constitutes the greater part of the infant’s experience, and throughout life is retained in the intense experiencing that belongs to the arts and to religion and to imaginative living, and to creative scientific work.” (Donald Winnicott, Playing and Reality, 19)

-AK]]]]]

Along with imitation, practice is the other mechanism by which virtue—and anything else—is learned. Insofar as Locke’s young gentleman is virtuous, it is due to “habits woven into the very principles of his nature” (32), which have been formed by repeated practice and reinforced with praise. It is only by means of repetition that behavior becomes embedded into the pupil’s nature, and thereby becomes natural—or, to use a favorite word of Locke’s, “easy.” At several points Locke invokes a corporeal analogy—just as grace or “carriage” is achieved only through steady, prolonged practice of a bodily discipline like dance, so too is ease in mental operations the product of repeated exercise.