A NOTE ON THIS PAGE

This page continues the discussion thread from weeks 1-9 of the “NEW SCHOOLS” graduate seminar taught at Princeton in the Spring Term of 2023 (taught by D. Graham Burnett and Jeff Dolven; launch syllabus here). The last four weeks of the class centered on student presentations of “case studies”: specific experiments in pedagogy and political/social imagination. Entries below offer weekly readings and pre-class “think pieces” by the presenting students (three per week).

DGB & JD

* * *

CLASS 9

Readings

From NB: The London Mechanics’ Institute

J.C. Robertson and Thomas Hodgskin, “Institutions for Instruction of Mechanics. Proposals for a London Mechanics’ Institute,” Mechanic’s Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette no. 7 (October 11, 1823): 99-103.

“Public Meeting, for the Establishment of the London Mechanics’ Institute,” Mechanic’s Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette no. 12 (November 15, 1823): 177-182.

Thomas Hodgskin, Labour Defended against the Claims of Capital; or, the Unproductiveness of Capital Proved with Reference to the Present Combinations amongst Journeymen. By A Labourer (London: Knight and Lacey, 1825), 13-19 and 26-33.

Henry Brougham, Practical Observations Upon the Education of the People, Addressed to the Working Classes and Their Employers (London: Richard Taylor, 1825): 1-12, 15-22, and 27-33.

Charles Dickens, Hard Times Chapter I, Household Words IX, no. 210 (April 1, 1854): 141-145.

Nick also proposes a cornucopia of background sources, not required: Antonio Gramsci, “On Education,” Selections from the Prison Notebooks, edited and translated by Quentin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1971 [1926]), 162-191; David Lloyd and Paul Thomas, Culture and the State (New York and London: Routledge, 1998); Jonathan Rose, The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001); Dorothy Thompson, Chartists: Popular Politics in the Industrial Revolution (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984); E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1963), 235-253.

*

From NI: International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, Education Department

Vivian Gornick, The Romance of American Communism (New York: Basic Books, 1977 / Verso, 2020), pp. 3-9. (Complete book here.)

Arthur Gleason, Workers’ Education: American Experiments (with a few foreign examples), revised edition (New York: Bureau of Industrial Research, 1921), Chapter 1, pp. 5-17; + “Summary,” p. 60. (Complete book here.)

Fannia M. Cohn, “The Educational Work of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union,” in Report of Proceedings: Second National Conference on Workers’ Education in the United States (New York: Workers’ Education Bureau of America, 1922), pp. 52-66.

*

From AK: New Bauhaus/Institute of Design

László Moholy Nagy, Vision in Motion (Chicago: Paul Theobald and Company, 1969, 1st ed. 1947. Two excerpts: on photography (required) and the foreword, introduction, and first chapter (optional: they give a more general picture of the pedagogical philosophy at the New Bauhaus/Institute of Design). (Complete book here.)

PRE-CLASS THINK PIECES (NB & NI & AK)

[NI starts here]

For my New School, I wanted to explore an example of workers’ education in the US labor movement. In part this came from a desire to see how the “Progressive Education” movement that we have discussed around John Dewey interacted with social reform efforts in the “Progressive Era” more generally. Among the objects of reform in this period, the question of labor, and economic inequality, were of course central. Yet, so far in our course, many of the schools we have considered have demonstrated the application of progressive education on more middle-class or elite milieus: the Ivies with Veysey; CalArts with Womanhouse; Hampshire with the New College Plan; and Black Mountain College, for all its bohemianism, was populated largely by black sheep or dropouts of well-to-do families. Duberman points out that the unaccredited cloister of Black Mountain failed to attract black students partly, or precisely, because it rejected the promise of upward mobility that many black students sought from education, then and now:

“Not only was the artist at Black Mountain elevated ‘as a holy person,’ but the rest of the world was put down as ‘utterly corrupt,’ unclean. That cluster of attitudes made the community all at once cruel to and protective of its own – and monkishly indifferent to the world outside. […] Until she left in 1954, Flola Shepard remained active politically, but her only legacy (derived from ads she’d put in the local Negro press to locate black students) was the occasional appearance of two frightened black girls (apparently sponsored by a black lawyer in Asheville) who were driven back and forth to the college to take a few classes. It would have been amazing if anything more had resulted, since Black Mountain – unaccredited, and with a local reputation as a hideaway for freaks and subversives – was hardly likely to attract blacks anxious for entree into a middle class world.” (Duberman, 423-424)

While this passage underscores the particularities of black education, in the South in particular, I also see the “anxiety” Duberman identifies here as a broad motive that most underprivileged groups tend to ascribe to education: the promise of social mobility. The ideals of higher education are not lost on people who have to think pragmatically, but for those coming from precarious situations, so many things can get in the way of those ideals – time being a major one, and money being another.

The readings I assigned for tomorrow are organized around this question: what can education look like when working life cannot be fully suspended? And building upon that, how might we think of the space of education as *interrelating* with work, family, and political action, rather than being a place autonomous from “the everyday”? How could education not just reproduce, but reconfigure the social? If we want to pursue Gramsci’s claim (quoted by Hirschhorn) that “Every Human Being Is An Intellectual,” I think we’ll have to consider how the Intellectual might operate in everyday space – or at least, how one might not leave the everyday behind.

As it turns out, many experiments in American workers’ education formed all over the country in the first two decades of the 20th century, each addressing with these very questions in their own way (the TOC of the Cohn reading enumerates many other “experiments”). Some traditional colleges and universities attempted workers’ education initiatives, such as The Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers. New, independent labor colleges were also formed. In another version of this assignment, I could have pointed us to Brookwood Labor College, in Katonah, New York, often called “The Harvard of Labor,” which was the first and longest-lasting residential college started by the labor movement, of which Dewey was a friend, visitor, and advocate. Brookwood functioned basically like an upstate liberal arts college with co-operative elements and a specialized curriculum, and produced many leading figures in the post-WW2 labor movement.

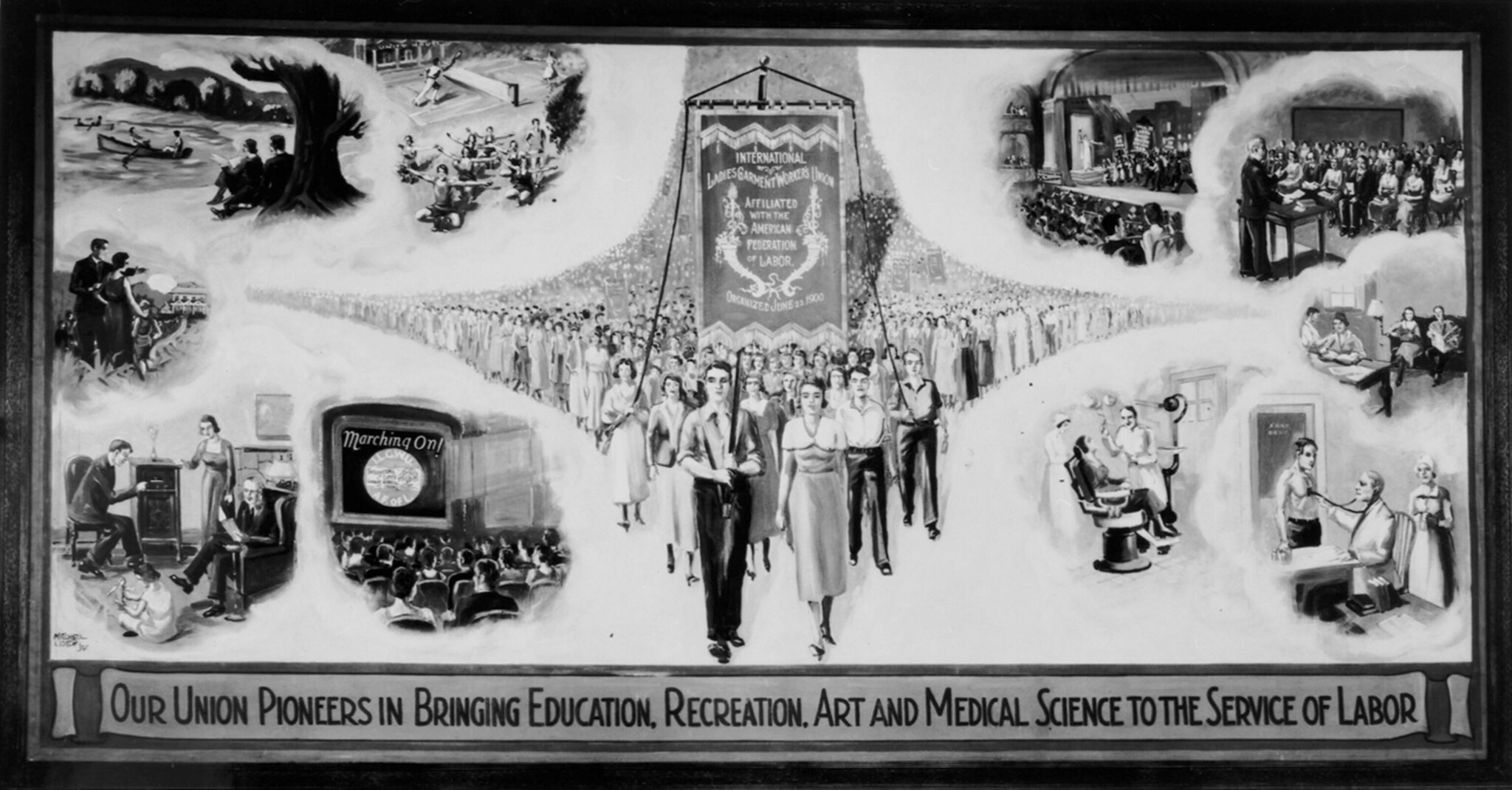

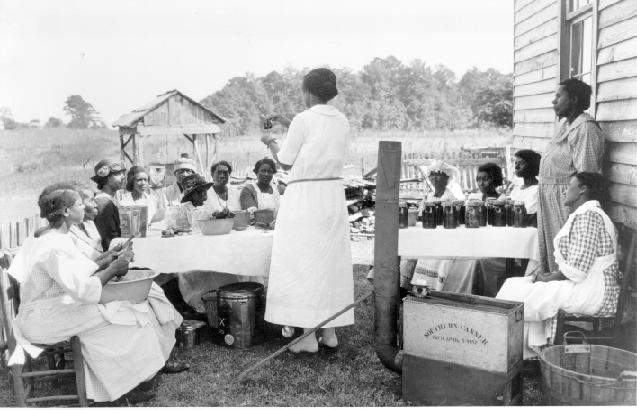

But instead, in order to draw a greater contrast to the models we’ve seen so far, I decided to focus on the International Ladies Garment Workers Union’s Education Department, established 1916 in New York, which was the most elaborate and visionary example of the most common type of labor school model: union-based education which occurred on weekends and evenings.

ILGWU was a fairly radical trade union, comprised of Jewish and Eastern European immigrants with socialist leanings, and many of its most radical leaders and rank-and-file were women. Its Education Department was envisioned and founded by Juliet Stewart Poyntz in 1916, and it was elaborated by her successor, Fannia Mary Cohn, starting in 1918. As you’ll see in the readings, the Education Department developed different modalities of education according to different degrees of engagement, commitment, and availability, as well as different ways of finding and identifying potential students (Cohn was also a co-founder of Brookwood and ILGWU regularly sent the most dedicated students there, on scholarship). English lessons were the main attraction for this generation of workers (we could talk about literacy education, recalling Freire), but from there a range of resources were available, including humanities courses and social sciences, but also less time-demanding social events, open lectures, and outings to museums and theatres. Health education was also a high priority, and something that my “experiment” will riff on.

For the readings, 3 short things: The Gornick, while a bit anachronistic to the ILGWU’s heyday (she is describing her childhood in the mid-30’s, long after the Socialist-Communist split), is the most vivid account I’ve read of the affective “inner life” of the working-class immigrant left in this period. I think it is helpful for peeling back the dogmatic rhetoric of many of this movement’s documents, and unsettling our post-Cold-War preconceptions of the old-left socialists as propagandized zombies. While most of the book is oral histories, Gornick opens autobiographically, setting up self-education as a transformative, humanizing aspect of the US Communists’ political project:

“I would point to one or another at the table and whisper to [Mother]: Who is this one? Who is that one? My mother would reply in Yiddish: ‘He is a writer. She is a poet. He is a thinker.’ Oh, I would nod, perfectly satisfied with these identifications, and return to my place on the bench. He, of course, drove a bakery truck. She was a sewing machine operator. […] But Rouben was right. Ideas were everything. So powerful was the life inside their minds that sitting there, drinking tea and talking issues, these people ceased to be what they objectively were – immigrant Jews, disenfranchised workers – and, indeed, they became thinkers, writers, poets.” [6-7]

The labor colleges were attempts at bringing this educative impulse out from domestic space into social space – to build institutions for and around it.

The other two readings are more procedural pedagogy documents: the Gleason outlines the overall philosophy, methodology, and problems of the Workers’ Education movement in this period (and uses ILGWU as an example); and Fannia Cohn’s report elaborates the specifics of the program of the Department as of 1922. In both, a question I’d like for us to consider: how do these documents rethink the idea of education entailing class ascension? How do they attempt to separate education from assimilation into polite society (which would entail estrangement from the workers’ movement)? To put it another way: how could Gornick’s parents’ friends become “thinkers, writers, poets,” yet remain workers?

Further reading, in case it’s helpful for anyone:

Richard J. Altenbaugh, Education for Struggle: The American Labor Colleges of the 1920s and 1930s (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990)

Susan Stone Wong, “From Soul to Strawberries: The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union and Workers’ Education, 1914-1950,” in Kornbluh & Fredericton, eds., Sisterhood and Solidarity: Workers’ Education for Women, 1914-1984 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984)

Radical Approaches to Adult Education: A Reader, ed. Tom Lovett (London: Routledge, 1988)

The Re-Education of the American Working Class, eds. Steven H. London, Elvira R. Tarr, and Joseph F. Wilson (New York: Greenwood Press, 1990)

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education, ed. Robert H. Haworth (Oakland: PM Press, 2012)

Studies in Socialist Pedagogy, eds. Theodore Mills Norton and Bertell Ollman (New York/London: Monthly Review Press, 1978)

[a slideshow of images of the ILGWU ED and its environments can be found here. – NI]

* * *

[AK starts here]

Nathan Lerner’s “Light Box” Exercise at the Chicago Bauhaus

The New Bauhaus, founded in Chicago in 1937, was the brainchild of the Association of Arts and Industries, an organization composed primarily of leaders from the Chicago business community. Since its inception in 1922, the Association’s stated aim had been “impressing upon the industries of the central west the great importance of improved artistic design as a national asset in world competition,” through, among other means, the establishment of a design school that would supply local industry with professional designers. The Association’s board determined to found a school on the Bauhaus model and, after an unsuccessful attempt to lure Walter Gropius away from Harvard, engaged former Bauhaus instructor László Moholy-Nagy as its founding director. The New Bauhaus would operate for just one year under the auspices of the Association of Arts and Industries, closing in 1939 after breaking with the organization and reopening later that same year as the renamed School of Design (its name would change a second time, to the Institute of Design, in 1944—for the sake of clarity I’ll refer to it here as the Chicago Bauhaus). However, long after its rupture with its initial backers the Chicago Bauhaus retained its close ties to industry and designed its pedagogy to meet the needs of industrial production.

In his correspondence with the Association of Arts and Industries prior to his appointment, Moholy expressed his confidence in the “universal validity of the teaching principles of the Bauhaus,” and the “possibility of adapting them in America.” In the U.S. at the time of the school’s founding, the ground was being prepared for the postwar educational landscape described by Jamie Cohen-Cole in The Open Mind. Already in the interwar period, creativity was coming to be seen as an essential ingredient of social cohesion and economic success. Determining who was creative and why, and how to make more people more creative, was regarded as critical to educating the nation’s citizenry and training its workforce.

Moholy’s pedagogical program for the Chicago Bauhaus was guided by a humanistic belief in creativity as a universal capacity, not limited to art or artists but possessed by all and touching all forms of human experience, and by a conviction that creativity could be instrumentalized to at once serve and transform the ends of industry. One of the articles of faith of Moholy’s Bauhaus pedagogical philosophy was the belief that “Everyone is talented” (Ein jeder Mesch ist begabt). This maxim would remain a guiding principle of Moholy’s work at the New Bauhaus and its subsequent iterations; it would live on at the school even after his death in 1946, but tellingly, it would be revised in later years to “Everyone is creative.” Creativity was the essential ingredient of design and the most valued characteristic of the designer; it was also a design object—as a later observer of the Chicago Bauhaus would remark, “Imagination is the product.”

Moholy located the basis for creativity in sensory experience. “Everyone,” he claimed, “is sensitive to tones and colors, everyone has a sure ‘touch’ and space reactions, and so on.”This was a position characteristic of what Leah Dickerman has termed the “elementarism” of Bauhaus pedagogy, which presupposed the existence of a set of universal, a priori psychophysical responses to sensory stimuli. In Moholy’s lexicon these responses were the “ABC of expression” (what he referred to in German as Grunderlebnisse or Urerlebnisse): “those timeless biological fundamentals of expression which are meaningful to everyone.” The pedagogical program at the Chicago Bauhaus began with a set of foundational exercises designed to encourage experimentation with the properties of color, surface, tone, form, and space as “the first step to creative production before the meaning of any culture (the values of an historical development) can be introduced.” The ultimate end of this “sensory training” was twofold: to confer an understanding of the common psychophysical basis of experience; and to activate the whole sensorium and unify it under the crowning faculty of “vision”—a term that implied not mere sight but the embodied formal and spatial awareness that was the foundation of creative production.

*

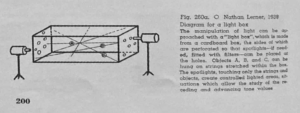

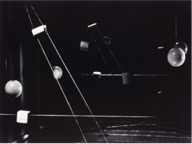

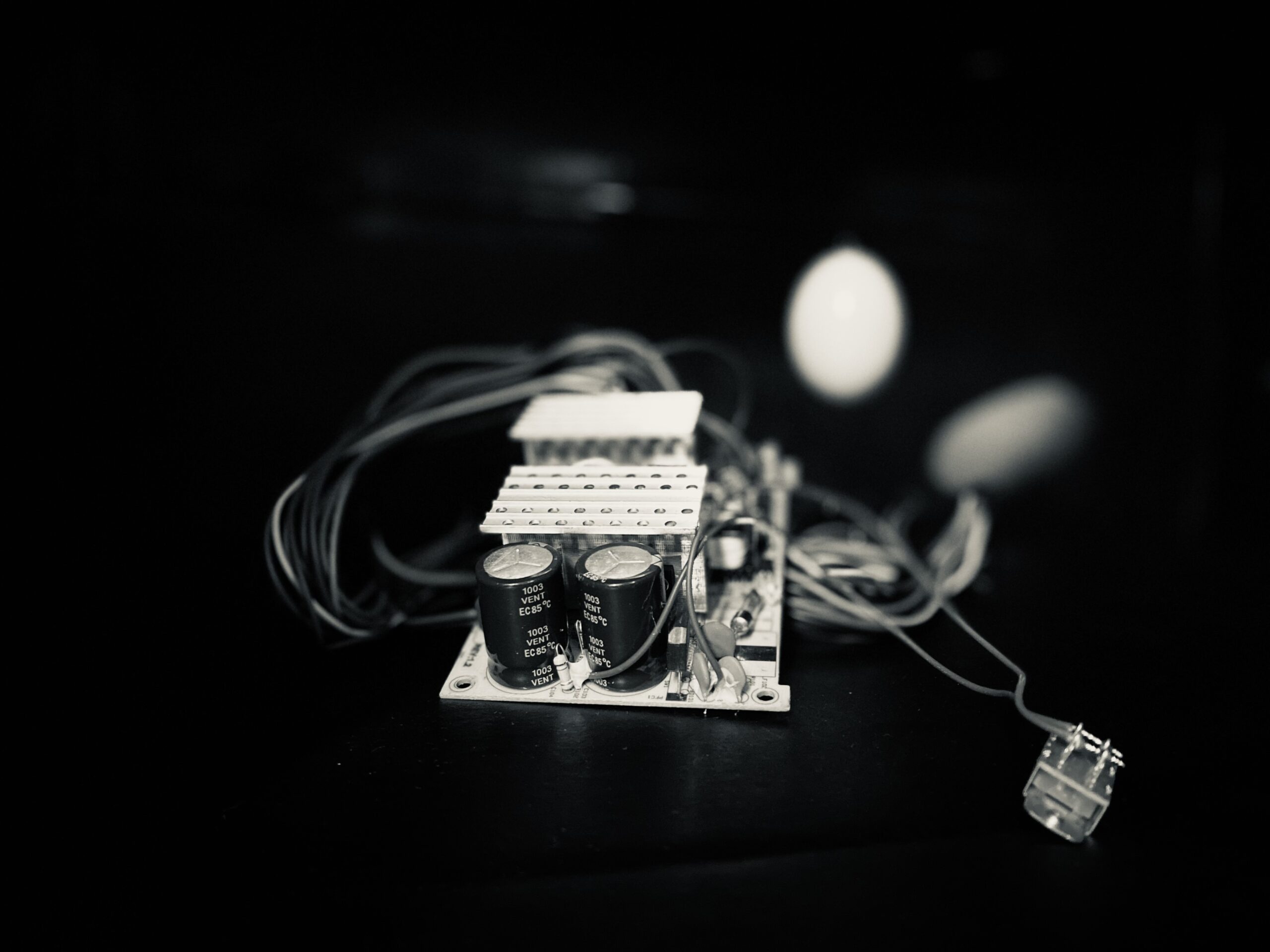

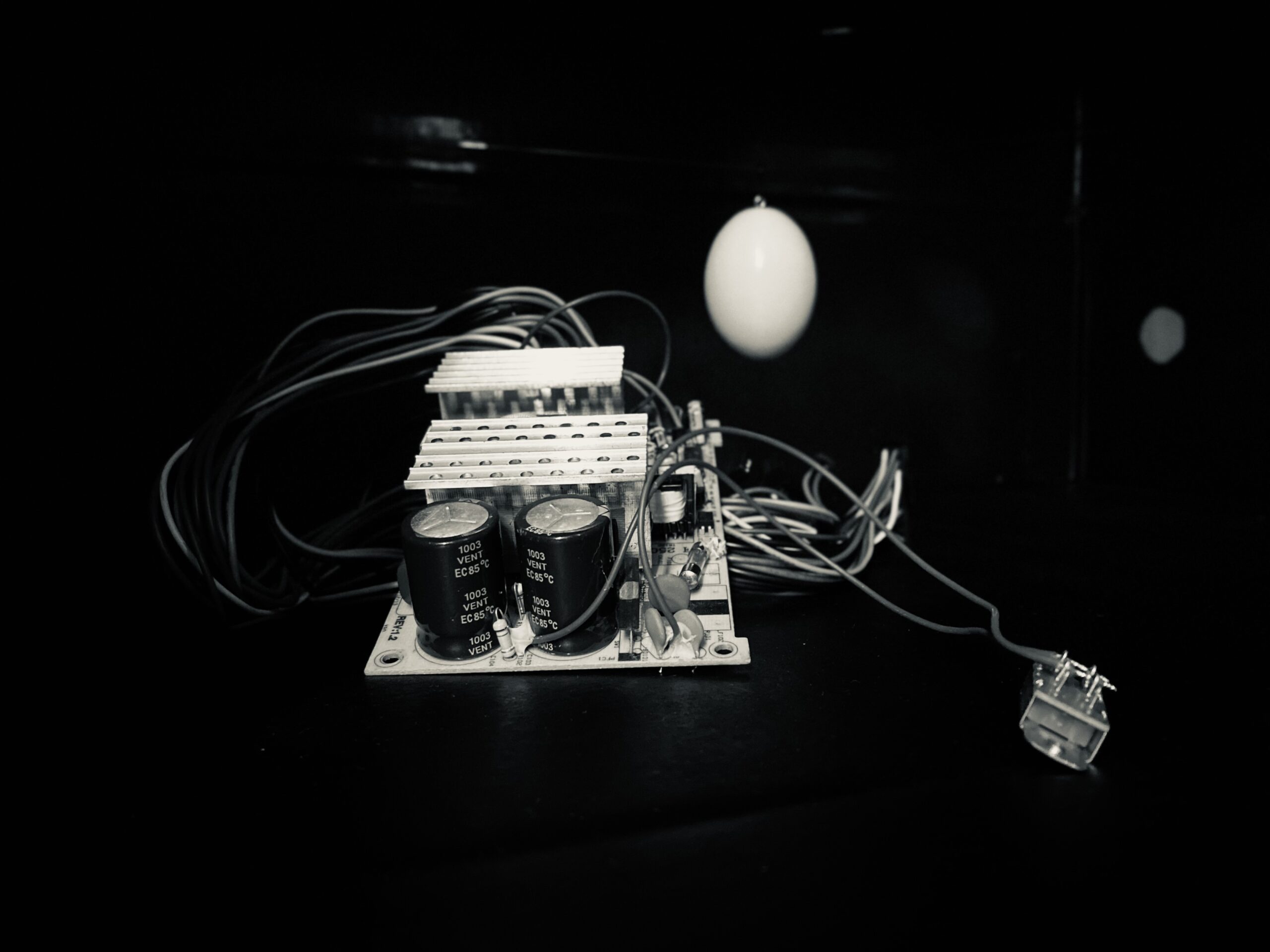

We’re going to do one of those “sensory training” exercises together in class. It was taught in the preliminary photography course at the Chicago Bauhaus and was invented by Nathan Lerner, a student in the school’s inaugural class who stayed on as an instructor. (Lerner is best known today for two things: designing the bear-shaped honey bottle and acting, along with his wife, as the executor of the estate of his tenant, the so-called outsider artist Henry Darger.) Lerner’s exercise, called the “light box,” involves repurposing a cardboard box as a kind of photography studio in miniature, in which small objects can be arranged and photographed under controlled lighting conditions. According to Lerner’s diagram of a light box [Fig. 1], reproduced in Moholy’s posthumously published Vision in Motion (1947), one of the long sides of the box is left open, while its ends are perforated so that lights can be shone through the holes. The interior is painted black. Strings are stretched at various heights and angles across the interior of the box so that objects may be suspended from them. Objects are placed or hung in the light box, a light or lights are positioned at one or more of the holes, and the assemblage is photographed through the open side of the box.

The purpose of the lesson was to teach students to photographically render the surface and volume of objects and the spatial relationships between them by means of directed light. This, it was hoped, would attune students to the interactions of form and light in the world at large. Lerner, for his part, used the technique extensively [Figs. 2–8] and claimed that it inflected the way he saw and photographed; he went so far as to compare urban space itself to an immense light box—an analogy he made literal in a photograph of laundry hanging on clotheslines strung across an alley, in which clotheslines line takes the place of strings, brick walls replace cardboard ones, and hanging clothes and fire escapes fill the container as if they were assemblages of dowels and crepe paper [Fig. 9].

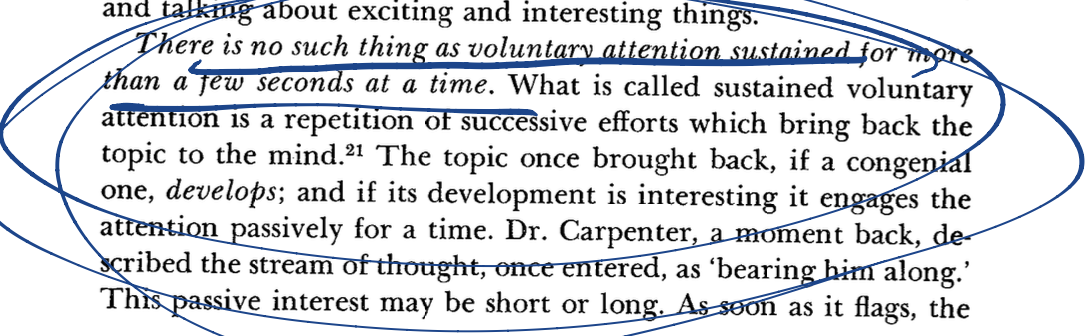

Lerner, quoted in Vision in Motion, described the light box exercise in characteristically elementarist terms:

With this simple device a great measure of control over light can be exercised. But aside from its value as a method for experimenting in a new medium, it has a further general value.

For light is one element; material object another, and the relationship of one to the other makes up our visual world. In the light box they become easily understood elements of visual communication. The light box, therefore, has significance for any artist. Working with it can give him a deeper insight into the visual-psychological elements that play an important role in making pictures exciting and meaningful.

The logic of the exercise was experimental, in the sense of experiment as “testing under controlled circumstances” put forth by Diaz in The Experimenters. The dark interior of the light box was for Lerner a controlled environment in which visual experience was analyzed and synthesized: separated into its component parts—light and material—out of which photographic compositions were constructed. By manipulating and configuring these “visual-psychological elements” under the experimental conditions of the light box, it was hoped that students would come to better understand the nature of their complex interactions in the visual field of everyday experience and learn how to synthesize meaningful visual communication out of them. Implicit in this program was a faith in a common substructure of psychophysical responses to form which underlay the complex and differentiated aesthetic experiences of individuals.

*

We’ll be splitting into groups and working with three light boxes—I’ll give a brief demonstration before we get started, but I haven’t had the chance to experiment with the boxes too much, so we’ll all be learning what works as we go. We’ll be using our phone cameras to photograph, so if you can, do make sure your phones are charged. I’m looking forward to trying this out with you all!

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

* * *

[NB starts here]

Along the conceptual lines NI elegantly traced above, I also chose to investigate pedagogical efforts aimed at workers, though in this case, the context is early nineteenth-century Britain. While this selection partially reflects my own academic training and investments, I figured it might be generative to think through class-targeted experimental education at the historical juncture in which the modern British proletariat was “made” (per E.P. Thompson’s formulation). Some questions guiding my inquiry and demonstration: What intellectual and experiential resources did the different founders of the London Mechanics’ Institute tap into when designing the institution? What strategies did they devise to reach and engage people who spent most of their waking hours at work? How did they define “useful knowledge” and which subjects, bodies of thought, or epistemological configurations (metaphysical speculation? Poetry and art?) were excluded from that category? How did they conceptualize the relationship (or distinction) between physical and intellectual labor? What did education mean in practical terms to these men in the era before compulsory mass schooling, in which the few schools that did exist were mostly controlled by the Church of England or competing religious sects?

Historical-contextual speed-run: By the mid-1820s, the British working class was in a particularly embattled state, reeling from the economic aftershocks of the Napoleonic Wars and the state’s intensifying repression of radical political activity and combination (proto-unionization) efforts, including mutual improvement and friendly societies which often sponsored collective education programs. After Britain’s victory at Waterloo in 1815, agricultural protection was reinstated (causing food prices to skyrocket), the state’s massive war debts had to be serviced, and, most importantly, tens of thousands of demobilized soldiers returned to an enervated economy marked by high unemployment, low wages, and an overburdened Poor Law system. In 1819, Parliament estimated that there were at least 120,000 pauper children in London alone. As Britain scaled the heights of European (and indeed global) geopolitical hegemony, its domestic social order appeared on the verge of catastrophic collapse. Along with electoral disenfranchisement and exclusion from most mainstream schools (again, mostly controlled by local parishes and churches, which, even with subsidies, could be prohibitively expensive), these developments narrowed the few educational opportunities on offer for working-class people.

Percy Shelley’s poem “England in 1819” perfectly instantiates the political-cum-affective atmosphere of post-Napoleonic Britain––and also serves as a nice TL; DR:

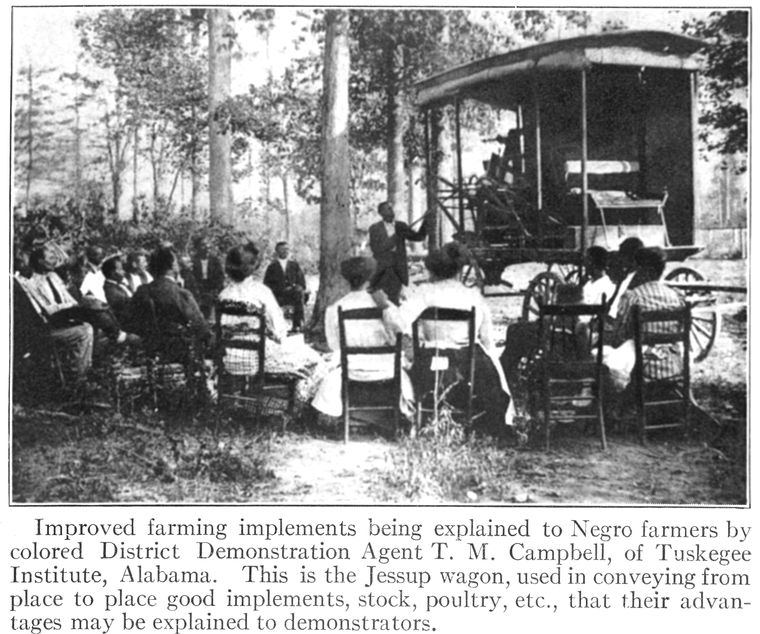

It was within this social-structural and ideological matrix that two radical writers, Joseph Robertson and Thomas Hodgskin, launched the London Mechanics’ Institute in 1823 to spread “those facts of chemistry, mechanical philosophy, and of the science of the creation and distribution of wealth” to the city’s male working-class denizens through irregular, nighttime, and/or weekend classes. The word “mechanic” during this time referred to any (usually literate) skilled worker and included furniture-makers, blacksmiths, tailors, potters, metallurgists, cutlers, shoemakers, weavers, cartwrights, coopers, carpenters, and ironworkers (to simplify a complex etymological debate I only vaguely understand).

Today, the LMI is called Birkbeck College, University of London and has, though passing through different institutional permutations and arrangements in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, expanded into a large degree-granting research university with an endowment of £10.2 million. Its alumni include Marcus Garvey, Britain’s first Labour Party Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, and Bear Grylls, host of Man vs. Wild. Former faculty members include Eric Hobsbawm, Slavoj Žižek, and T.S. Eliot.

J.C. Robertson worked as a patent agent in England’s rapidly expanding print industry, while the (at the time) more politically militant Hodgskin had established his reputation through his 1813 polemical critique of military hierarchy and the enervating psychic effects of arbitrary authority, published after his discharge from the Royal Navy (what we would now call in the States a “dishonorable” discharge). The two met earlier in 1823 in Edinburgh, where they learned of an autonomous, part-time educational cooperative launched by Glasgow’s skilled workers, the Glasgow Mechanics Institution. This occurred after the artisans broke with the middle- and upper-class leadership of the “Andersonian Institute,” an adult education center funded through the bequest of former Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow John Anderson, and organized their own member-funded school. Robertson and Hodgskin sought to replicate their success in London and quickly attracted small donations from the abolitionist William Wilberforce, the radical pamphleteer William Cobbett, the utopian socialist Robert Owen, and Lord Byron. In the early days of the LMI (late 1823 through 1824), thousands of workers flocked to the twice-weekly lectures held in a chapel in Moorgate. It is crucial to note, too, that the vast majority of unpropertied workers could not vote or run for office until the Second and Third Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884-1885. Women could not vote at all until 1918 (propertied and over the age of 30) and 1928 (every adult over the age of 21).

However, Robertson and Hodgskin’s leadership was quickly eclipsed by the well-connected and wealthy Benthamite physician George Birkbeck, who emphasized moral reform/temperance and “apolitical” bourgeois respectability as opposed to the original founders’ dreams of working-class intellectual independence and insulation from the “philanthropy” (ideological hegemony) of the leisured classes. The LMI was relocated from the humble, rented church space in Moorgate to a newly constructed theater, adorned with a portrait of Birkbeck, in Holborn. In nineteenth-century discourse, Holborn was metonymically linked with the legal profession. Two of the four legal professional-accreditation organizations, the Inns of Court, were and still are based in the neighborhood. The class dynamics instantiated by this move were clear. As one anonymous radical activist would complain in 1832, “Let the huckstering owners of the misnamed Mechanics’ Institution, and the would-be rulers of mechanics’ minds, see that the day is gone by when the million will be satisfied with the puny morsels of mental food which aristocratic pride and pampered cunning have been wont to deal out to them. Let them see, in reality, that ‘the schoolmaster is abroad.’” (The Poor Man’s Advocate and People’s Library, February 25, 1832: 44; quoted in Lloyd and Thomas, Culture and the State, 103).

Accordingly, the most intense curricular debates centered on political economy, starkly dividing the reformist-Benthamite patrons courted by Birkbeck (including the lawyer and parliamentarian Henry Brougham, the author of one of our readings) from the emancipatory political vision sketched by Hodgskin and Robertson. The latter abandoned the project altogether, while Hodgskin, though dismayed by what the LMI had become, continued to teach there. As Richard Clarke writes:

“The Utilitarian liberals had no problem with the ‘facts’ of science, but their ideas about the ‘facts’ regarding the creation and distribution of wealth were very different from Hodgskin’s. Very different too was their vision of the consequences of education for the ‘mechanics’. Both were based on ‘self-help’, but for Hodgskin, self-help meant collective action to secure fundamental social change; for the Utilitarians sobriety, thrift and individual self-improvement were the route to personal advancement and social progress. …By 1825 Hodgskin and Robertson, having instigated the idea of an Institute, regarded it as a lost cause, whose existence depended on the ‘great and the wealthy’” (5).

As implied by one of my earlier questions, the LMI, especially in its original form, was notable for its relative lack of attention to art and literature at a discursive moment characterized by persistent Coleridgean/Carlylean claims that individual capacities for aesthetic perception and production were atrophying under industrial capitalism. Lloyd and Thomas have a fascinating riff on this (p. 89):

Many of the questions I wanted to pose to you all have already been articulated perfectly by NI above (to repeat: “What can education look like when working life cannot be fully suspended? And building upon that, how might we think of the space of education as *interrelating* with work, family, and political action, rather than being a place autonomous from “the everyday”? How could education not just reproduce, but reconfigure the social?”) NI also rightly identified the unsettled status of social mobility in proletarian pedagogic theory (especially for the most vulnerable and precarious populations within the wider WC) in the twentieth century. There is a certain resonance there with the moral-reformist impulse animating both the radical and moderate wings of the LMI, articulated in the language of “self-help” and “improvement” (though here it is more of a psychological and ethical category than an economic one). However, as we’ve seen, these terms were deployed toward quite different ideological ends by the Hodgskin and Birkbeck/Brougham camps. On what conceptions of collective or political life, individual cognitive and intellectual capacity, and labor’s value did these contending usages of “improvement” rest?

I conclude with Dickens’s scathing opening chapter of Hard Times, set in the classroom of the delightfully detestable Thomas Gradgrind. Gradgrind, along with Satan from Paradise Lost, Mrs. Grundy from Archie Comics, Prince Musidorus and others from Philip Sydney’s The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia, Dr. Bledsoe and Ras the Exhorter from Invisible Man, the schoolmasters from Pink Floyd’s The Wall, Hollis Lomax from John Williams’s 1965 novel Stoner, Edna Krabapple from The Simpsons, and Ben Stein’s character from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, occupies a vaunted position in the Pantheon of Bad Educators.

Though Gradgrind was likely modeled on the utilitarian James Mill, Dickens, in his public lectures at various mechanics’ institutes (he served as President of the Chatham Mechanics’ Institute in Kent for over a decade) in the 1840s and 1850s, consistently railed against narrow, instrumental conceptions of pedagogy that “neglect[ed] the fancy and the imagination[.]” Do you see any resonance between Dickens’s acerbic satire of psychic-epistemic mechanization in Hard Times and any of the attitudes towards education expressed in the assigned primary sources? How might we view this chapter in light of the Lloyd/Thomas-Gramscian critique cited above?

The exercise/demonstration I’ve cooked up for tomorrow depends on a certain pedagogic immediacy, so I’ll refrain from specifics for now. More soon!

* * *

POST-CLASS POSTS

[DGB starts here]

I think the idea here is that JD and I are not going to try to résumé/document our seminars across these next four weeks. That was a Week 1-8 thing. So much of what concerns us now with these “Cases” involves the practical immediacy of the lessons/exercises/activations that you all are leading — and that are happening live in the room when we are all together. Where there is relevant documentation of those encounters, let’s put it up here in the chat thread (see below for some pics already posted from AK’s thing). And generally, where there are thoughts or comments, everyone should feel free to use this space as a pinboard. But the emphasis going forward wants to be on the pre-class posts composed by the seminar leaders.

All that said, I do have a few quick thoughts after the three wonderful presentations/projects we did today (led so engagingly by AK, NB, NI).

They were all totally great!

For me, important “take-homes” were the encounter with orality (in NB’s “lecture”), and the element of surprise or expectation that ran through all of them in different ways. With AK that was simply the delight at walking into the room and seeing how much work had been done to set something up for us. With NB that was the sense that “anything could happen” because of the performativity. With NI I had the sense we were going somewhere specific, but I could not tell where (so there was a sense that I was headed for a “reveal” — and I was not disappointed in that regard).

When JEHS noted the Jacotot-ness of the afternoon (the sense that we had enacted, three ways, a kind of everything is in everything pedagogical proof-of-concept), I found myself feeling that my delicious/expectant “anything might happen” joy-suspension might actually be a kind of affective corollary of the proposition that everything is in everything. This felt interesting.

After class, musing to myself about the goodness of what had happened, my thinking circled the question of “a class” — not in the socioeconomic sense (though that was on my mind, of course, in the wake of NI’s presentation in particular), but rather in the sense implied by “school.” You all, we all, are…a “class.” In what ways was the goodness of our session today a result of the way we have become a “community of inquiry” across these weeks? Which is to say, what is the role of (emergent) community in the actual project of teaching/learning? I know that is the actual question that a number of our texts (e.g., Duberman) wrestle with explicitly. But I suppose it really hit home today. I felt it as a puzzle. Part of what made class good was…us. You. The openness and willingness you brought — that we all brought. We were all “game.” And so much can be so good when folks are “game.” But how is that condition of possibility achieved? And maintained?

-DGB

* * *

[CA starts here]

Our group’s composition, from its first to final stages:

[OK CA, I’m seeing what you were saying about the rave-to-battlefield progression. On the subject of the battlefield, there’s a really interesting article by Robin Schuldenfrei on the involvement of the Chicago Bauhaus with the war industry during the Second World War. Schuldenfrei describes how experiments with artificial light and light manipulation informed Moholy’s work with Chicago’s Civil Defense Commission, a group tasked with camouflaging Chicago against air attack, and how they were incorporated into a course on camouflage design offered at the school under the auspices of the Office of Civilian Defense. She mentions that two light boxes were included in an exhibition of the Camouflage Course’s work “to show how light and shadow could conceal the character of forms” (111). -AK] — researching this now, Thank you! -CA [[[I had the wrong link in there for the Schuldenfrei, but the article previously linked to, by Emma Stein, actually goes into greater depth about the role of photographic pedagogy in the school’s war work. Both worth a read! -AK]]]

* * *

[AK starts here]

Some process shots of the moody colonnade created by CA, NB, JD, EH, PH, NI, and JEHS, courtesy of DGB:

A few photos by DGB of the composition by CB, DGB, CF, and TU:

And another from TU:

* * *

[JD starts here]

I was thinking after class a little bit about this idea of a class, too, though in terms of—structure, I suppose, is the most neutral term, what parts it has and what relation they have to one another. Especially, whether and when a class abstracts from its proceedings to account for what has been said or done, the reflexive operations of summary or so-what. On what basis would a structural analysis of a class proceed?

Possible paradigms or auspices for structural analysis include the sentence (syntax), narrative, argument (logic), and rhetoric (as a series of speech acts). (Some of these may be derived from others, e.g. Barthes’ project of developing a narrative structuralism from syntax.) These preliminary thoughts are partly narrative, partly rhetorical, I think.

It was AK’s light-box exercise that got me started thinking about this, because the question arose, with five minutes to go, whether we would try to talk together about what had happened. You could I am sure talk about the various overlapping micro-structures of practical experiment involved in our manipulations in those dark little rooms, but basically, it was an open space of immersion without organized reflection. Just trying things, talking miscellaneously, trying again. Then there was open time for a few remarks and then we were done. The lessons about e.g. Bauhaus elementarism were mostly implicit or ad hoc—though not the less powerful for that? (Or even, the more?)

NB’s session with the Mechanics Institute was much more structured: there was a priming question, for writing (how can you do your job better?); a ten-minute lecture on the history of seminar instruction; and then discussion, in pairs, then in the whole group, of the lecture in relation to that initial question. We moved from mode to mode—private writing to collective listening to open discussion to a kind of summary reporting out. A series of discrete events, and in this, like a narrative? (A story if so of what? Of the formation, the consolidation of a community?) But the relation of the events to one another was variously rhetorical: a question, narration (setting forth the facts), division (breaking down the problem, here in discussion), and epitome (pulling it together, or something like that)? Different movements of dilation and economy, with a privilege given to that final stage of summary.

And then NI, who started us off talking about the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, which had the function both of orienting us in the reading material and also raising some questions—an open seminar discussion, of a sort that could simply occupy the hour, with more or less marked moments of recursiveness and summary inside it. But there was a second part, which focused us on health, especially oral health, and invited us to think in relation to our own experiences (the rhetoricians would call this testatio, or, wonderfully, martyria). Finally, there were—pH strips for each of us! An experiment? An example? A little difficult to say, but it seemed to put what had happened so far to test or proof, without much opportunity afterward for discussion (except the weird, powerful sense that such a direct inquiry into each person’s oral health brought us back around to questions of insurance and workers’ precarity with which we began). Structurally so interesting—how would the class have been different if that were the first thing that we did? (How would its rhetorical status have changed? It might be more clearly and example, less a proof? Or a puzzle?)

Anyway—this is hardly systematic, and as with many such enterprises, it’s not clear what the return would be for developing a proper, comprehensive terminology, architecture etc. (Barthes goes a good distance with narrative, with considerable self-assurance, but never really takes up his tools again; one could think too of Empson’s seven types, which are more of an excuse for thinking than they are boxes for sorting.) But—the basic questions of parts, order, and especially recursion (when and if the class becomes about the class; or in what sense different of its events represent transformations of other events); well, it’s something to think about! And it’s a little more tractable to analysis than whatever was the solidarity and bonhomie that carried us so happily through the session—though I too tip my hat gratefully to that.

-JD

* * *

CLASS 10

Readings

From TU: Gudskul

Ruangrupa and the Artistic Team, “Lumbung” and “What Is Harvest,”in documenta15: Handbook. Kassel: Hatje Cantz, 2022. (File: Documenta15Handbook)

Ruangrupa + Team Majalah Lumbung, “Editor’s Introduction lumbung Connect and Interconnect,” in Majalah Lumbung: A Magazine on Harvesting and Sharing. Kassel: Hatje Cantz, 2022. (File: IntroLumbung)

Maulida Raviola, “Probing into Gradiasi: lumbung as a Medium, for the Management of Movement Knowledge,” in Majalah Lumbung: A Magazine on Harvesting and Sharing. Kassel: Hatje Cantz, 2022. (File: Gradiasi)

Dedy Hermansyah, “Harvesting Rice, Caring for lumbung, Keeping Traditions,” in Majalah Lumbung: A Magazine on Harvesting and Sharing. Kassel: Hatje Cantz, 2022. (File: Hermansaya_HarvestingRice)

Melani Budianta, “Equal Lumbung of Culture: Poso Women’s School,” in Majalah Lumbung: A Magazine on Harvesting and Sharing. Kassel: Hatje Cantz, 2022. (File: PosoWomen’sSchool)

“Serigrafistas Queer,” in documenta15: Handbook. Kassel: Hatje Cantz, 2022. Please also google them. (File: SerigrafistasQueer)

Please consult this website and focus on the concept of nongkrong: https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/lumbung-members-artists/gudskul/.

Please consult the lumbung rules: https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/easy-lumbung/.

*

PH: Education in Ecovillages // The School of Integrated Living

Read: About SOIL / Earthhaven Mission and Goals / SOIL Values and Code of Conduct / SOIL Compositions (aka curriculum)

Marshall B. Rosenberg, Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life, (Encinitas: PuddleDancer Press, 3rd Edition 2015), Introduction, pp. 1-14; Chapter 11 “Conflict Resolution & Mediation,” pp. 161-184; Chapter 13 “Liberating Ourselves and Counseling Others” pp. 195-208.

(and for those that prefer having a PDF, page numbers are as follows: Intro pp. 24-38, Chapter 11, pp. 208-239, Chapter 13 pp. 254-268).

–

Additional Reading:

M.E. O’Brien & Eman Abdelhadi, Everything for Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune (Brooklyn: Common Notions, 2022).

Benjamin Walker’s Theory of Everything, “Utopia (part ii),” 2017.

Karen T. Litfin. Ecovillages: Lessons for Sustainable Community (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014) Chapter 6 “Consciousness: Being in the Cirlce of Life” pp 149-186.

Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality (Great Britain: Calder & Boyars, 1973).

Jason Hickel, Less is More: How Degrowth will Save the World (London: Heinemann), Chapter 1 “Capitalism: A Creation Story” pp 43-77.

*

From CA: Drawing Restraint

Johan Huizinga, “Nature and Significance of Play as a Cultural Phenomenon,” in Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1949.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Invention within Limits,” in Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Alfred North Whitehead, “Lecture Two: Expression,” in Modes of Thought. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1938.

*

PRE-CLASS THINK PIECES (TU & PH & CA)

[CA starts here]

In 1987 while an undergraduate at Yale University, the artist Matthew Barney produced a series of performances that continue to evolve today collectively called DRAWING RESTRAINT. Barney entered Yale on a football scholarship with the intention of studying pre-med but soon changed his degree to studio art after coming to the realization that his obsession with self-inflicted experiments of physical endurance and psychological willpower would be more readily accepted in the arena of performance studies than the medical laboratory. During these performances, Barney would first manufacture a device that limited his ability to reach a set goal, which could be as simple as reaching a drawing board or marking a ceiling, and then placed himself in the device to act out the challenge with varying success. These devices ranged from sculptural barriers to bondages designed to restrict movement to prosthetics. For example, in DRAWING RESTRAINT I (1987), Barney wore a harness connected to a thick bungee-cord that bound him to the wall of a classroom and then attempted to climb up a steep ramp stretching himself against the tension of the cord to set pencil to paper positioned on a desk at the other side of the room.

In these performances, Barney approached art making as athletic conditioning, as a sport, a game, one that he set the rules for but also one that allowed those rules to be rewritten in real-time should certain interventions unfold. Interested in pushing his bodily and mental threshold, Barney used the DRAWING RESTRAINT exercises to test his capacity to withstand repetitive physical stress, tension, resistance, but also to play, improvise, and collaborate. I have no doubt that at times his exercises were meant to cause him pain, to measure his tolerance, but I think what has been underemphasized in academic studies of DRAWING RESTRAINT is his willfulness to play. In one of the primary sources I provided, Johan Huizinga examined play as a foundational element of cultural and historical production and asked what play is in itself and what it means for the player. He wrote:

“It goes beyond the confines of purely physical or purely biological activity. It is a significant function-that is to say, there is some sense to it. In play there is something “at play” which transcends the immediate needs of life and imparts meaning to the action. All play means something. If we call the active principle that makes up the essence of play, “instinct”, we explain nothing; if we call it “mind” or “will” we say too much.” (Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (1944): 1)

Barney would perform all hours day and night, not just for class or in front of an audience. Some performances were documented, some witnessed, while others remain unknown. Was he playing? Playing and seriousness are often treated as a dialectic — something that Huizinga has been criticized for in secondary literatures. “Play lies outside the antithesis of wisdom and folly,” wrote Huizinga, “and equally outside those of truth and falsehood, good and evil. Although it is a non-material activity it has no moral function. The valuations of vice and virtue do not apply here” (1944: 7). Can play not be work? Can the imaginary not produce the real?

There is something that does not sit well with me when reading the critics of Huizinga who claim that his was an attempt to categorically define play into taxonomies. While it is evident that Huizinga thought of play as being separate from ordinary life, I think he did so as a strategic methodology to examine how rules in play form group relations. Like Barney in his earliest iterations of DRAWING RESTRAINT, which were all performed within his studio space, Huizinga set artificial perimeters to his study as a means to operate under controlled conditions and take notes along the way. Athletic training, in which the body strives to surpass threshold after threshold of corporeal limitation, is at the center of DRAWING RESTRAINT. These early performances demonstrate Barney’s objective to create a “hypertrophic process” — an endless loop between desire and discipline, and ultimately, a self-enclosed aesthetic system.

Performance as pedagogy has for centuries been valued and studied. Theater was typically centered, but over the last century, the discourse around performance and performativity has undergone a revolution. Performance studies contribute to and draw from the currents of feminist, critical race, postcolonial, and queer theory discourses. The first American theatre department was the Carnegie Mellon’s School of Fine and Applied Arts in 1914. When performance served the innovations of Fluxus artists in the 1960s, visual art pedagogies altered dramatically. As artists experimented with the durational, environmental, and embodied techniques, schools around the country found it necessary to incorporate performing into an otherwise “fine” curriculum. Indeed, Fluxus could have been my “school” for this seminar, although making it so would have raised debate about whether or not Fluxus can be said to still be in practice as a “school.” In the 1970s, artist Augusto Boal began a series titled Theater of the Oppressed to promote student engagement in a set of highly interactive games, exercises, and techniques designed to excite participants in a “problem-posing” dialogue. And it is easy to find similar themes to those exposed here in the practices of Shigeko Kubota, Linda Montano, and Tehching Hsieh.

Performance that requires endurance is now considered to be a critical modality of expression in human behavior, social processes and hierarchies, identity deconstructions and constructions, and educational programming, with teachers and students alike seeking to better understand it for the benefit of their own field as well as a pedagogical method. For these reasons, it was difficult to choose only a few primary texts. And there are plenty of great reads, from texts about speech-act theory by John L. Austin (1962) to the phenomenology of gender in ritualized repetition of communicative acts by Judith Butler (1995). Then there is Elyse Pineau, who described performance through the ideological meanings it bears and the temporal axes it operates within:

“It precedes and creates the condition for action; it is instantiated anew in each moment, and it is carried forward through each repetition. In other words, if “performance” is the situated instantiation of historical meanings, “performativity” is the sociocultural dynamic that lends it longevity, power, and the appearance of inevitability. Thus, one might attend to discreet performances within educational life while investigating the performative trajectories in which they are embedded… Critical performative pedagogy combines acute physical awareness of one’s kinetic and kinesthetic sense with candid and thoughtful consideration of the implications of those bodily sensations. Every time that we ask students to perform across gender, ethnic, or generational lines we have the opportunity to unpack their resistance to the unfamiliar, their stereotypic assumptions about how others move through the world, as well as to confront their own habituated responses and experiences.” (Elyse Pineau, “Performance Studies Across the Curriculum: Problems, Possibilities, and Projections” (1998): 133)

These and other scholars have shown that linking performance to pedagogy within the classroom without an accompanying recognition of historical, social, or cultural antecedents is problematic. Rather than viewing performance as merely a theatric, or assigning the reductive metaphor of teacher as performer, it should be understood as a humanizing pedagogical framework that helps teachers and students interrogate their collusion in the social construction of meaning and excavate new conditions of knowledge production.

Over a couple of years, the DRAWING RESTRAINT performances grew increasingly complex with more difficult obstacles to overcome. Fellow student at the time, Sophie Arkette, observed that Barney’s works “do not refer to something static, a composed form, but reveal the way one action precipitates another in the course of making a work” (Art Safari No. 1, video recording). For Barney, the game itself is less important than the accumulation and release of energy in a controlled corporeal environment. Later in the 1990s, Barney incorporated the DRAWING RESTRAINT performances into long-format films and expanded their meaning, identifying a three-part internal system that processes the ebb and flow of energy in the body toward and away from productivity. He called the first level of the system “Situation” to indicate pure potential and described it as the first six weeks of embryonic development when the embryo is both XX and XY and is thus undifferentiated.

The second level is called “Condition,” which he distinguished as a “disciplinary funnel” that like a digestive tract, processes energy and distills it for use. The final level is “Production” in which the outcome is realized. Notably, however, Barney often chooses to skip over “Production,” short-circuiting the system so that the internal matrix continues to oscillate between “Situation” and “Condition.” He wrote on the subject, “Something that’s really elusive can slip out — a form that has form but isn’t overdetermined” (Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, Travels in Hypertrophia (1995): 117). What becomes clear when you watch his work is that if you stay in “Production,” you have swallowed what he calls “The Hubris Pill,” and are doomed to stasis. On this three-tiered system, Barney has explicitly vocalized that concepts put forth by Bourdieu were important to his thinking, especially Bourdieu’s habitus, or the tendency for people to behave and think in a certain way because of socialized norms. Bourdieu defines habitus in the primary sources I provided:

“It is the object of explicit injunctions and express recommendations, sayings, proverbs, and taboos, serving a function analogous to that performed in a different order by customary rules or genealogies. Although they are never more than rationalizations devised for semi-scholarly purposes, these more or less codified objectifications are, of all the products of habitus structured in accordance with the prevailing system of classification, those which are socially recognized as the most representative and successful, those worthiest of being preserved by the collective memory; and so they are themselves organized in accordance with the structures constituting that system of classification.” (Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice (1977): 98)

Habitus is, for Barney, a good (and by good, I mean bad) way to die. It is the state you find yourself in if you reach “Production” and fail to return to “Situation.” Habitus prevents us from accessing the energy, the movement, within the domain some might call “practice” and others might call “self.” At stake here is the problem of determinism — of how corporeal aspects of embodied subjectivity is directed by social determinants. Recall that the most generative level of Barney’s system is represented by an embryo that has yet to differentiate to XX or XY. Here again, I was tempted to add Butler to the required reading list for this week and I encourage you to seek out their scholarship. Butler has written extensively on biological reductionism and, not unlike Bourdieu, rejects gendernaturalising roles of symbolic orders.

Since the 1990s, the DRAWING RESTRAINT performances have taken new form beyond Barney or any one institution or movement. Listing out the numerous pathways would require another think piece, but for now, I can share a picture I took while attending one in 2019. Organized by six female artists, this DRAWING RESTRAINT took place in a warehouse in Queens.

– CA

[TU starts here]

I would like to start this think piece by asking: what is lumbung? (I am really interested about this concept and how it has been applied by Ruangrupa and all the collectives in documenta and in Gudskul) And I will leave the answer open until our session starts on Wednesday afternoon. Maybe because I don’t know the answer yet (or because I don’t want to know the answer), which I think it’s a good way to start. Maybe, because it’s good to leave it open as the concept reminds us. What I would like is for you to think about this concept and to bring something for the beginning of our session. Something short, not so developed, something from your own experience. We will start from here. Hopefully we don’t find an answer to the question that is triggering this think piece, but instead we find multiple and diverse answers. Multiple broad, diverse, open, and broad answers.

When we think of a school we could think of many different things. But maybe we would agree at some point that is a place where knowledge is shared. When I started thinking about a school for my presentation/project/activation, I was thinking a lot about how knowledge was transferred and how it was kept/used/stored/shared. I was thinking a lot about what it means to know something, and that in many Western educational systems knowing something differentiates people from others: the people who know from the people who don’t. Themes largely developed in Ranciere’s The Ignorant Schoolmaster, and Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. What I want to reinforce here is that in these structures knowledge appears as an individualistic thing tied to narratives of progress and personal development. How many times have we heard about the importance of knowledge in regards to the job market? What is our relationship to knowledge, do we conceive it as a collective practice or as an individual thing? How we could think of knowledge as a space for resistance? What is the real value in generating and sharing knowledge?

In a lumbung, knowledge is shared. This is to say that lumbung carries with it the notions of collectivity and interwinedness. In its traditional sense lumbung is the collective practice of harvesting crops. But as reminded in the reading about the Poso’s Women School, lumbung is not only a collective harvesting practice in its literal meaning, but also a cultural practice. A cultural practice that is shared by the community in the consecration of their goals. It is a practice of sharing knowledge in a way that things are held together. This idea of gathering and storing knowledge is the essence of the lumbung practices: to collect the “entire wealth of values, knowledge, and social practices as regards the identity of the (a) village” (Budianta, 67). Lumbung is the practice of creating togetherness.

There is also another characteristic of the idea of lumbung that I would like to share here, the idea of lumbung as a modular practice. Lumbung knowledge could be “placed according to the context of the space where the participants are located.” (Raviola, 164). As per Raviola, the modularity of lumbung dissolves authority actions and transforms them in circular and creative collective actions. Knowledge sharing is presented then as a circular and reflective practice, in which the members of a community negotiate to keep the collective interests of the community alive. So modularity provides the possibility of keeping the flow of knowledge and reflection in constant fluctuation. I will quote the last question posed by Maulida Raviola in “Probing into Gradiasi: lumbung as a Medium for the Management of Movement Knowledge,” in which se asks: “how can lumbung truly provide a transformative action for the movement of and not stop as merely interest group?” (Raviola, 165). I would like us to reflect a little bit about what this question means, and to reflect on how it is our approximation as knowledge as a practice.

Gudskul is presented as an educational knowledge sharing-platform, structured around the concepts of sharing and working together. Maybe these two concepts summarize why Gudskul sparked some interest in a sense to start thinking-with it. Gudskul is structured under the concept of lumbung, and this is why it is so interesting. It doesn’t intend to be something defined and structured, it intends to stay open. If we think of Gudskul, we need to think of an ecosystem, a system in which every participant affects the others. Each of them is defined by the interaction with the other members of the community. Gudskul is an educational practice.

Maybe this is the fascinating thing about Gudskul and lumbung. The conception of thinking of a school, or a platform, as an ecosystem that implies a collective practice. It is not only a practice, but a practice of practices. A collective of collectives, in which knowledge is circulated to activate other activities. I really like this, Gudskul is not only a “school” it’s a practice, documenta15 has nothing to do with an art exhibition. It’s practice! A shared one.

Finally I would like to reflect or dedicate some lines to Serigrafistas Queer. A collective that participated in documenta 15 and has been highly influential in the activities that we’ll be conducting together. In short Serigrafistas is also a collective working with collective care practices, sharing and knowledge circularity (please check the file submitted into the readings for this week and try to google them if possible). Because Gudskul is structured under the concept of lumbung, and lumbung is a collective of practices. I’ll be inspiring my activities in some collective exercises developed by Serigrafistas in the framework of documenta15. The idea is to think about ourselves in relation to others and how our actions are affected and affect others.

These activations were also influenced by Donna Haraway’s “Playing String Figures with Companion Species.” It was my intention to include this whole text as a required reading for the week but I preferred to include more lumbung related stuff and leave here a little reflection of what inspired the activation. I will finish here with a little quoted paragraph and look forward to a nice time together. A time of sharing and reflection (please notice that my activity will happen outside, so please be prepared to spend some time below the sun beams.

On the practice of string figures by Haraway:

Practice = Action

-TU

[PH starts here]

The School of Integrated Living (SOIL)

In 2018, I quit my job as a project manager at an architecture firm and started driving west to Taos, New Mexico. I was moving to Europe soon and the goal was twofold: use the transition as an opportunity to take an adventure and draw my knowledge of conventional construction closer to “regenerative” at the Earthship Biotecture Academy. Around halfway, I stopped in Rutledge, Missouri to partake in the Dancing Rabbit Ecovillage weekend experience (and to stay at what I thought might be a nice place to camp). Reflecting on my inaugural visit to an intentional living community, the first thing I can think is that 24 years old feels worlds apart from 29…but I’ll try to sketch a picture.

Besides my own, there are no cars, save for four sitting in a big open shed at the edge of the village, alongside stacks of reclaimed lumber, that all 75 members of Dancing Rabbit share. We pitch our tent, scoop woodchips over humanure in an outhouse, take a lap through 20 acres of native prairie grasses (a sliver of the 280 acres of rolling hills and woodland), and share a meal with fellow visitors and residents alike at the Milkweed Mercantile Inn. Sharon—who teaches most of our workshops—is gray-haired, gentle, and welcoming. They have dirt floors inside their home and chickens circling it outside. Their husband has recently died, and we connect over being fellow Citizens’ Climate Lobby members. Stephen with the round, 2-story house lives there just some of the year, and for the rest, sells Christmas trees in New York and travels around to various odd jobs. Alis built himself a literal hobbit house and explains the process one goes through to join the community. Cutting up apples from last season at Sara and Ted’s house, we learn that Sara is one in a collection of midwives. Later on, I adjust to the experience of swimming nude at the lake, and my brain rewires as Ted and his middle-school-aged daughter do the same. Each person at Dancing Rabbit seems to know and be deeply committed to their role and shows up to it not just as doers, but as teachers. Everyone has something different to offer—skills or knowledge—which they freely and generously share, in hopes that we will carry it forth into the networks we belong to. It is evident residents are as committed to changing the world as they are to changing their own lives, and education is essential to this mission.

While for centuries, small groups of people have come together to seek new ways of living in harmony, ecovillages trace their roots to various historical lineages: the ideals of self-sufficiency and spiritual inquiry found in monasteries, ashrams, and Gandhian movements; the environmentalist, peace, feminist, and alternative education social movements of the 60s and 70s; and both “back-to-the-land” and cohousing movements in affluent countries. GEN’s original vision—for new ecovillages to “sprout like mushrooms”—has not come to pass. Instead, ecovillages form something more akin to a mycorrhizal network, transmitting information from the bottom up through educational programs offered all over the world.

Contrary to popular opinion, ecovillages are not isolated enclaves but culturally, architecturally, economically, and climactically diverse communities that hold in common a strong educational mission. The Global Ecovillage Network (GEN) was established in 1995 and today includes around 400 ecovillages worldwide, a number which swells to 15,000 when including traditional rural villages in the Majority World that belong to participatory development networks within GEN. Formed under the GEN umbrella in 2005 and now a part of the UNESCO Global Action Programme, Gaia Education is an international NGO that teaches participatory processes in all four areas of regeneration: social, cultural, ecological, and economic. Gaia’s Ecovillage Design Education (EDE) curriculum culminates in a hands-on project designed and implemented by students under faculty supervision, most of which export ecovillage practices into existing communities (building shared gardens, establishing environmental education programs for children, transforming sewage systems in urban slums) and are undertaken by graduates who have never lived in an ecovillage. The cost of land has slowed the growth of new ecovillages, but courses emanating from them are more popular than ever, fulfilling Gaia’s mission to promote both information exchange among ecovillages and to provide education for widespread social change.

Earthaven is a “living laboratory for a sustainable human future” in the Blue Ridge Mountains about a 45-minute drive southeast of Asheville, North Carolina. Established in 1994, the 320 acres of jointly owned forest has steadily taken on 100 residents (75 adults and 25 children). Their mission is to live sustainably and to serve as an educational center. Karen T. Liftin captures the spirit and function of education at Earthaven in the book Ecovillages: Lessons for Sustainable Community, which she wrote after a year of visiting intentional communities across North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia:

“Brian Love and others like him have acquired economic assets as a direct consequence of the impressive skills they’ve developed at ecovillages. Brian’s skills include carpentry, masonry, plastering, insulation, concrete casting, excavation, grading, logging, lumber processing, setting up renewable energy systems and wastewater systems, as well as construction management and building design. In addition, there are the skills in law, accounting, and financial management that are necessary to handle any project that interfaces with a larger community and the communication skills – verbal and emotional – necessary for living in a community. Part of an ecovillage economy is the education that comes along with it.” (78).

Unsurprisingly, both the most challenging and the most rewarding aspect of ecovillage life for the 150-plus residents Liftin interviewed was: “the people” (113). Author and longtime Earthaven resident, Diana Leafe-Christian, distinguishes between strategic and relational people. “Strategic people are goal-oriented and focused, energetic, and often blunt in their manner. Relational people are process-oriented; for them, the strategic movers and shakers are like bulls in a china shop. To strategic thinkers, relational people are self-indulgent wimps” (Liftin 119). Ecovillages often attract people who urgently want to build a different future and people who are seeking deep connection, a combination which spurred Earthaven to adopt non-violent communication (NVC) after a conflict over whether or not to build wells in response to the state health department declaring their spring-fed water system unfit for visitors. While many ecovillages operate by consensus, others have elected “king guides,” super-majority voting, or sociocracies (wherein decision-making is decentralized to specialized subgroups). Communication is arguably the most foundational aspect of intentional living communities, and many have developed and exported techniques and forums that draw on improvisational theater, and collective mediation, which build essential capacity to respond to our own and others’ suffering—a kind of intelligence that guides our evolution and interconnects us with other human beings.

As self-proclaimed living laboratories, ecovillages often function like one big classroom. The ultimate outcome of people living in an evolutionary laboratory is a relational experiment that fosters new modes of human beingness. Wendell Berry suggests that spirituality and practical life should be inseparable—practicality alone can be dangerous and spirituality alone feeble, and neither is very interesting without the other. If spirituality can help translate intrinsic connections with nature into lived experience, what does this look like in practice? Where does the scientific method fit in? Like Outer Coast, the School of Integrated Living incorporates hands-on teaching methods which diverge sharply from the intellectual status quo of traditional educational institutions. Many of the SOIL compositions are deeply focused on spirituality and the development of self-awareness and relation to others. On the metaphysical spectrum, ecovillagers share a core belief in the power of the group mind—the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Practicing such a unified worldview seems to offer an advantage in dissolving old polarities between simple living and big-picture thinking, religion and science, and secular and spiritual. If every culture lives out its core story, what kind of cultural stories does the education that takes place in ecovillages have to offer?

–PH

* * *

POST-CLASS POSTS

[DGB starts here]

Lots to think on again this week. TU gave us a wonderful series of exercises with a rope and those schematic narrative diagrams.

Yes, we had to get over a moment of initial awkwardness (it would be interesting to theorize that perennial threshold of something like polite caution). But once we got going the format proved to be a remarkably efficient way to get a group of people generating and (in some sense) “performing” collaborative stories. In fact, I felt it worked so well that it was slightly haunted, for me, by the specter of well-grooved “team-building exercises” such as turn up at expensively curated corporate retreats. I want to be clear: I am not in any way saying this as a critique of TU’s lesson! On the contrary. The people who run those retreats are total professionals who have refined absolute best practices for facilitating group dynamics. (I have some friends and former students who have moved into the “coaching” world, who have reported to me about the high-quality understanding of group dynamics often on display among the leaders in that growth area — an area about which it is easy to feel ambivalent, though perhaps wrongly?). I more found myself puzzling over how strange it is that an entire industry has arisen that services that very real need — and that this industry has arisen pretty much totally without connection (in either direction) to university/classroom situations. Is this correct? Maybe. I am not sure. Still, I found myself wondering in this direction. A genuinely remarkable and catalytic lesson — one that I would like to do again in another group situation, because I feel like it really “worked.”

*

And with PH’s lesson on Non-Violent Communication we really “went there”: drilling pretty close (in at least some instances) to the heartland of our emotional and interpersonal lives — those spaces of conflict, misunderstanding, love, hope, hurt. Her care in setting up the circle and providing for our needs surely contributed to the sense of safety that enabled many of us to take a turn into this territory. After the role-play exercise, we went around the group. What was most “alive” for each of us there on the grass? Different things: the status of the silence we had permitted ourselves (its place in spaces of thought); the denaturing function of certain forms of “structure”; the careful maintenance of distance that can sometimes thwart genuine love and intimacy, but at other times is an absolute condition of possibility for both. (How close were we, in all this, to the “encounter session” class that Martin Duberman tried to run on this campus circa 1970? What was different? What would those students recognize in our physical configuration? In what we actually said?).

In this lesson the tie back to the question of educational community was left nicely in suspension: SOIL communities apparently use NVC practices, and so we were dropping right in on the “discourse” understood to make possible a certain kind of utopian community of teaching and learning. The rules for the governing of these special places (in the reading) provided a nice window into the kind of “constitution” that can undergird “flatter” forms of intentional co-living. And such forms of life clearly enable forms of pedagogy quite different from the dominant paradigm within modern American higher education.

*

And then, finally we descended into the basement for the harness and blindfold, for elastic bungees and the problem of restraint. Much of this will be better invoked in a gallery of judiciously selected images (see below). Does everyone know the Lars Von Trier film The Five Obstructions? It activates in its own way the problem of constraint — as well as the problem of reenactment. Also very relevant (especially for the physical aspects of the Matthew Barney exercise): the work of the path-breaking choreographer Elizabeth Streb.

Many thanks to TU, PH, and CA for three really interesting lessons today — and thanks to all for being willing to jump in on the explorations…

-DGB

* * *

[JD starts here]

That was a remarkably safe space (the lawn, the basement), given the range of our lessons this week, so maybe it’s a little perverse that I found myself meditating afterward on pedagogy and violence—not a topic we’ve broached so far, but an old and evergreen one. I couldn’t find any hint of hurt in TU’s irenical exercises in lumbung, hybrids of Harraway and Serigrafistas Queer. The project of translating from drawings to configurations of body and line to stories felt alert and adaptive and just about immune to coercion. PH’s nonviolent communication protocols encouraged an open attentiveness to the real needs of others, and it felt in my own exchanges, and those vibrating around me, that everyone gave themselves pretty fully to the invitation to role-playing. NVC assumes that when those needs are surfaced, they will be benign and meetable: Marshall Rosenberg opens his book, “Believing that it is our nature to enjoy giving and receiving in a compassionate manner,…” But I and others were struck by SOIL’s Code of Conduct on “Honoring Boundaries”: “I honor others’ boundaries as well as set and honor my own. When I honor someone’s boundaries, it is a sign of respect. I understand that if I continue to say or do things that violate other people’s needs after being asked to stop, protective use of force may be used.” Nonviolence is a negation of violence. What is the root assumption here—Rousseau or Hobbes?

Of course all this got a twist from our experiments with Matthew Barney’s Drawing Restraint. There is a world of thinking about restraint and pleasure that ought to be adduced. Likewise, the resources of disability studies. But for our immediate purposes, I felt like a kind of analysis was being performed: that a tangled knot of effort, pain, constraint, making, gender, consent, complicity, was being untangled by the open inventiveness and collaborative invitation of the exercise as CA posed it. That is, here was effort, and even small pain, not as consequences of hierarchical violence—rather, as chosen experiences and allegories (both at once—the feeling and the availability for thinking) of the difficulties that attend any act of creation. It was not punishment. Au contraire! But its elements are often recruited to punish. Maybe more fundamentally, it was not violent, not in the slightest, and so we got to think, in the heat and after, about how what makes a relation violent and what saves it from violence.

These are questions for any school. Where and when can or does violence happen? Among students? (Informal or outlaw regimes of discipline and hierarchy.) Teachers punishing students? Or administrators punishing students? Or is violence outsourced beyond the building—onto kin, onto police? When it is imposed, how is it imposed—in private, in public? (What is its relation to shame?) How much violence is tolerated among students before a response, violent or otherwise, is triggered? How is the threat of it invoked in the course of ordinary business, if at all; how is it interpolated into pedagogy? (The great Jesuit media theorist Walter Ong has a famous article on “Latin Language Study as a Renaissance Puberty Rite.”) Is there a theory of pain and learning, pain and memory? (Ditto, shame?) And of course one could also ask—how does the school respond to violence outside its walls, in the society at large or in its past? That is a powerful theme for some of the schools we have seen, from the anticolonialism of Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Paulo Freire to the restraints on beating in Locke and Rousseau. Violence might be said to shape the care with which many of the educators we have read create the spaces of their schools. How do they keep violence out?