William Catalog Entry

Nadia Huggins’ vision as an artist is undeniably tied to place, and certainly to home. While human experience is most often her main focus, a comprehensive viewing of her work reveals a fixation on the natural landscapes and seascapes of St. Vincent and the Grenadines as a motivating force. Examining the three photographs from “Caribbean Queer Visualities” in this light, though it is not thecentral feature of any of the photos, relationship to home appears a key part of how the subjects express their unique i-mages. With the map in The Architect, the wood in Self Portrait, thedeep blue expanse in Fighting the Currents, and the subject’s position in all three, Huggins shows how desires for the preservation of, acceptance in, and peace with home are crucial elements of crafting the Black Caribbean woman’s destiny and conception of self.

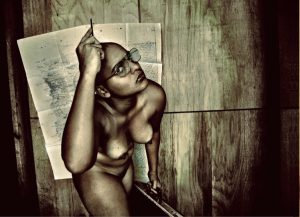

Of the three photographs, The Architect most plainly features Huggins’ home, with a map of St. Vincent and the Grenadines hanging on the wall behind her subject’s nude figure. Most of the map is obscured, but to the subject’s right can be seen the clearly demarcated west coast of the island. The nude woman stands concealing the map with a suspicious, side-eyed look about her face, leaning forward into the lens in imposing stance. She brandishes the suitcase and tool in her hands with a solid grip, presenting them almost as arms of self-defense.

woman stands concealing the map with a suspicious, side-eyed look about her face, leaning forward into the lens in imposing stance. She brandishes the suitcase and tool in her hands with a solid grip, presenting them almost as arms of self-defense.

Her demeanor appears a challenge to the viewer to remove her from this position, a display of resolve to protect the map and thus the island. In the postcolonial context, this is a powerful position for her to take. As an architect presiding over the map of her island, she becomes the avowed steward and developer of its territory, effectively taking the job over from patriarchal, colonizing forces. Symbolically, as an independent Black woman, she asserts and presents her unadulterated identity in the image of the island, carving out a new self-image while preserving the island’s treasure as committedly as Cesaire’s Caliban does for himself and his fictitious birthplace. As Caliban simultaneously defends his land while breaking Prospero’s hold on his self-identifying language, Huggins’ preservation of home and pioneering Caribbean womanhood go hand in hand, one not surviving without the other.

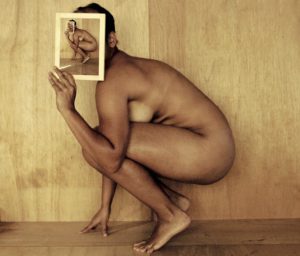

Self Portrait — Infinity is more subtle in its connection to place and home than The Architect. In this piece, Huggins herself holds a framed picture with infinite photographs of the same scene within, one of her crouching precariously on a wooden surface. Huggins’ choice here of unvarnished, light-brown wood on which to portray her body is interesting. She masterfully uses a golden wood grain that resembles her own skin tone, an only slightly darker brown, with lighter areas matching the wood. Like some of Huggins’ artwork, such as Black and Blue, this choice blurs the boundary between the Black body and its surrounding environment. Fascinatingly, though her body fits in visually with the wood, she still crouches in an awkward pose, resting the entire weight of her body on her fingertips and toes.

One way to understand this is that the material itself is rough and splintery, that to assume a more relaxed position would be uncomfortable on her bare skin. This idea, in light of the photo’s inclusion in Caribbean Queer Visualities, is fascinating insofar as it could speak to her inclusion in the society of her home. Though she may fit in visually with the material, perhaps to say that she may not at first appear dissimilar to the world and her peers around her, her queerness and wo manhood set her apart, relegating her to a disposition of of wariness almost alike to a fearful chameleon, eager to blend in but careful not to expose too much of her uniquely unacceptable body and mind to the elements. Like Ian in A Small Gathering of Bones, she tentatively sits at the boundary of acceptance and otherness, not sure of how to at the same time become one with her home and with herself. She reveals to the reader or viewer the infinity of her struggle, as the external i-mage of her struggle plays out over and over again in her mind. She authentically presents her body and mind, but is perpetually not at home with her surface and surroundings.

manhood set her apart, relegating her to a disposition of of wariness almost alike to a fearful chameleon, eager to blend in but careful not to expose too much of her uniquely unacceptable body and mind to the elements. Like Ian in A Small Gathering of Bones, she tentatively sits at the boundary of acceptance and otherness, not sure of how to at the same time become one with her home and with herself. She reveals to the reader or viewer the infinity of her struggle, as the external i-mage of her struggle plays out over and over again in her mind. She authentically presents her body and mind, but is perpetually not at home with her surface and surroundings.

Where the first two photographs exude pride and ambivalence of home, the diptych from Fighting the Currents resonates of refuge, tranquility and peace. Featuring the side profile of Huggins’ face with a sea urchin projecting outward, a symbol discussed already as disruptive self-expression, the collage shows the sea as escape. It is the place where distinctive i-mage-making is best facilitated, since as Huggins describes on her website, “Gender, race, and class are dissolved because there are no social and political constructs to restrain and dictate my identity. These constructs have no place or value in that environment.”

In this part of her home, Huggins feels no duty to protect herself from outsiders, no need to fit her gender in, only to let herself flow forth in accordance with the natural beauty surrounding. Just as Elizete in In Antoher Place, Not Here imagines her escape to the jungle of Maracaibo, picturing vines sprouting from her Black body in righteous belonging, Huggins visualizes the pure marriage of humanity and marine ecosystem as producer of a refreshing i-mage — except that she is here, proudly making exercising self-discovery during a swim off the coast of her home island.

Lest mistake be made from this interpretation, interactions with home and place are not the overarching messages of these images at all. The photographs are first and foremost Huggins’ experiments with Philips’ i-mage-making, with how the Black woman’s body and experience in the Caribbean can be translated into ideas of the future. I am suggesting that, perhaps even subconsciously, Huggins’ subtle artistic moves are tied directly to her home, that home provides not just context, but substance to her subjects’ i-mage translations.

Work Cited

Brand, Dionne. In Another Place, Not Here. Vintage Canada, 1997.

Césaire, Aimé. A Tempest. Alexander Street Press, 2000.

Huggins, Nadia. “Transformations.” Nadia Huggins, 2017, www.nadiahuggins.com/Transformations-1.

Powell, Patricia. A Small Gathering of Bones. Beacon, 2004.