Huggins Collective Curatorial Statement

Nadia Huggins, in her artwork from “Caribbean Queer Visualities,” explores the relationship between subjects and backgrounds of digital photographs to conceive a new notion of what it means to be a queer Caribbean woman, and more generally, what it means to be human. Each photograph plays a unique role in demonstrating the internal power and agency required to create fresh, subversive self-image.

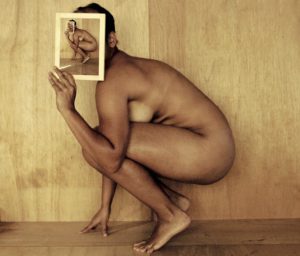

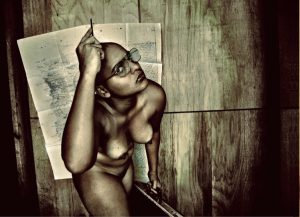

The Architect and Self Portrait — Infinity allude to the disconnect between the self-defined identity of a Caribbean woman and the identity thrust upon her by colonizers. Huggins’ black female subjects assert their bodies in unadulterated form, pushing back against a Western, patriarchal, and heteronormative gaze. In contrast, the diptych from Huggins’ project Fighting the Currents is more explicit in its portrayal of the discord surrounding self-image and perception. The digital photograph depicts, from Huggins’ face, an outgrowth of an asymmetrical, jagged, and disruptive identity jutting into the blue void of the ocean in the form of a sea urchin. This combination of both human and sea creature elements to create a bizarre, fantastical being may allude to the autonomous conception of a new identity. Clearly, in each photograph, the subject appears engaged in the process of image-making, of reaching inward and then releasing authentic product into the world.

M. Nourbese Philip, in the essay “The Absence of Writing or How I Almost Became a Spy,” discusses image-making. Philip pushes for literature to overcome restrictions placed on the Caribbean people by colonizers in the realm of self-expression, arguing that the only way for the Caribbean people to realize an authentic mode of communicating is to create a new language that harnesses the “emotional, linguistic, and historical resources capable of giving voice to the particular i-mages arising out of [their] experience” (81).

Philip centers on the concept of “i-mage” to explain the process of dismantling and reconstructing language and identity. Comparing the i-mage to the “DNA molecules at the heart of all life,” Philip suggests that the i-mage is a silent entity, the not yet manifested thoughts, grievances, and creations of an artist. It requires a fresh, unconventional “technique or form,” through which the artist can “translate the i-mage into meaningful language for her audience” (79). Thus, a person of societally subversive and unacceptable identity thrusts herself and her i-mage into the world with an appropriately matching device — one that subverts linguistic or other norms.

“The power and threat of the artist, poet, or writer lies in this ability to create new i-mages, i-mages that speak to the essential being of the people among whom and for whom the artist creates. If allowed free expression, these i-mages succeed in altering the way a society perceives itself and, eventually, its collective consciousness. For this process to happen, however, a society needs the autonomous i-mage-maker for whom the i-mage and the language of any art form become what they should be — a well-balanced equation” (Philip 78).

In The Architect, Self Portrait — Infinity, and the diptych from Fighting the Currents, the black Caribbean female subjects clearly demonstrate autonomy in the creation of their own i-mages. Instead of complying with the traditional constructs of gender imposed upon human societies at large, the subjects of these digital photographs redefine what it means to be simultaneously black, Caribbean, female, and queer.

The diptych from Fighting the Currents, for example, contributes to the themes of gender ambiguity and humanity prevalent in many of Huggins’ works. The outgrowth of the sea urchin from Huggins’ face alludes to the transformation of the subject into a being that is able to transcend conventional narratives surrounding established social categories, such as race, class, gender, and sexuality. In Self Portrait — Infinity, holds up a recursive photograph of the same image. Huggins’ use of the Droste effect in this piece serves to emphasize the depth of her own i-mage, and its production out of mental self-conceptions. The subject of the The Architect holds a writing utensil in her hand, suggesting that she is the architect or creator of her own i-mage.

Evidently, Huggins uses her artwork to challenge current perceptions about Caribbean art and Caribbean identity on an individual and collective level. According to Philip, the European response to African and Caribbean art has largely defined the narrative surrounding these aesthetics. Prior to the almost avant-garde “primitive stage” that many influential Western artists entered in the early 1900s, the African aesthetic was viewed as “primitive, naive, and ugly” under the Western gaze (Philip 79). As a result, both white Westerners and Africans of the diaspora dismissed this aesthetic. Philip claims that this shows that “Africans of the diaspora were so far removed from their power to create, control, and even understand their own i-mages” (Philip 79). The perception of African art only changed when Western artists employed the African aesthetic of art and sculpture in their work, indicating a lack of self-autonomous control over i-mage.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, for example, one of Picasso’s works from his Black Period, portrays five nude prostitutes, two of whom are depicted with African mask-like features. The masks worn by the two women invoke a racial primitivism, reiterating the common characterization of African art as backwards; they are appropriated to express the white female subjects’ aggressive rejection of the male gaze (Rossetti 146). Huggins seeks to push back against the primitive characterization that the Western world has imposed onto African and Caribbean art and identity in favor of a self-conceived i-mage. While Les Demoiselles d’Avignon alludes to the self-empowerment of white European women by using the masks to invoke the supposed primitive defense mechanisms of Africans, Huggins’ artwork endorses a genuine self-possession of Caribbean women by humanizing their forms as something other than primitive.

Another realm where mostly male artists challenge socio-political, colonial conventions to create their own i-mages not unlike Huggins is in calypso music, an integral part of culture in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Huggins’ home. In a 1930s recording of “Commissioner’s Report,” Trinidad calypsonian Attila the Hun rebukes colonial records of progress. In fiercely anti-colonial and leftist language, he sings that there is “no talk of exploitation / Of the worker or his tragic condition…no mention of capitalistic oppression” in a British report on rioting in its Trinidad colony. The artist communicates subversive i-mage here not by expressing immutable identity like Huggins and her subjects through gender, but by inserting a Caribbean worker’s standpoint into capitalist colonial discourse, by adding his experience, his side to what he calls a “one-sided” narrative.

The political inclination of artists like Attila the Hun becomes interesting in Huggins’ and Phillip’s context when considering their instrumentation. Specifically steel pan drum use, a crucial step in the development of calypso rhythm and song, can be traced to an 1881 British ban on percussion music in its colonies that led to the drum’s creation. When coupled with political content, the drum could be considered a subversive, unconventional and even rebellious technique of i-mage-making, the precursor to the overtly rebellious i-mages produced by these later musicians.

Attila the Hun imagines another future for the Caribbean worker with his provocative music, as Huggins does for the Black Caribbean woman in her raw, naked form. If the queer, Black woman Architect building her identity alludes in a way to self-determination in the face of oppression, the musician using instruments created under censure to write anti-colonial songs is a similarly empowering i-mage translation.

In an interview, Huggins expresses the belief that the sea offers individuals the opportunity to reimagine themselves in experimental and innovative ways. Through her artwork, Huggins harnesses her creativity to create new i-mages that use the sea and other environments and materials to do just this. Caught between tensions of male-dominated but autonomy-championing calypso music and the misrepresentative, patriarchal discourse of Western art, Huggins subjects seek new avenues of self-expression, ones that while rooted in Caribbean existence celebrate a multitude of marginalized identities.

Work Cited

Huggins, Nadia. “Transformations.” Nadia Huggins, 2017, www.nadiahuggins.com/Transformations-1.

Philip, Marlene Nourbese. She Tries Her Tongue: Her Silence Softly Breaks. Urban Fox, 1991.

“Picasso’s African-Influenced Period – 1907 to 1909.” Pablo Picasso’s African-Influenced Period, www.pablopicasso.org/africanperiod.jsp.

“Les Demoiselles D’Avignon, 1907 by Pablo Picasso.” Les Demoiselles D’Avignon by Pablo Picasso, www.pablopicasso.org/avignon.jsp.

Rossetti, Gina M. Imagining the Primitive in Naturalist and Modernist Literature. University of Missouri Press, 2006.

Ramm, Benjamin. “The Subversive Power of Calypso Music.” BBC, BBC, 11 Oct. 2017, www.bbc.com/culture/story/20171010-the-surprising-politics-of-calypso.

“Calypso Music.” Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias, enacademic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/105784.