Patterson Collective Curatorial Statement

On May 24th, 2010, police and military forces (800 soldiers from the Jamaica Defence Force and 370 officers from the Jamaica Constabulary Force) poured into the Tivoli Gardens district in the West Kingston neighborhood of Jamaica’s capital. [1] [2] At the time, the impoverished and crime-ridden Tivoli Gardens area was under the control of Christopher “Dudus” Coke, known by many as Jamaica’s most powerful “don.” [1] Referred to as “President” in the area, Coke’s standing in the community was recognized and protected by the nation’s then Prime Minister Bruce Golding, and his criminal enterprises had gone unchallenged by wary police forces since 2001, allowing Coke to grow a massive drug empire extending throughout several major U.S. cities, all from his base in Jamaica’s capital. [1] [2] In August 2009, the U.S. government requested Coke’s extradition on federal charges of trafficking in narcotics and firearms. After resisting the extradition order for months on end, up to the brink of diplomatic crisis, Golding ordered the official signing of the extradition order on May 17th 2010. One week later came the events that have come to be known as the Tivoli Gardens Incursion. [1]

“‘The objective was to establish law and order in a place where there was none,’ Karl Angell, a police spokesman, says. Media were prohibited from entering the area. The rest of Kingston watched as soldiers and police poured in and trucks carrying dead bodies drove out. Gunmen clearly fired on the security forces the moment they went in. … But the resistance melted away.” [2]

When police and military forces descended on Tivoli Gardens at 11 a.m. to apprehend Coke and his associates, they were met with gunfire. But by most accounts from people who witnessed the events, the security forces rapidly overpowered any resistance. [2] Many believe Coke and his gunmen to have fled Tivoli via its labyrinthine sewer system shortly after the police arrived. And police recovered a total of six guns during the raid, no match for the “machine guns, helicopters, and armored personnel carriers” the Army brought to the scene. [2]

“Some [police] used tissue swabs to test residents’ hands for traces of gunpowder. Often, the question of who was a gunman and who wasn’t was decided on the spot. If an unarmed man’s claims of innocence seemed unconvincing, the police might kill him.” [2]

Despite weak resistance and Coke’s early escape, the security forces carried out a ruthless crusade for “law and order,” spending the entire day rounding up residents and conducting extensive searches through the neighborhood’s houses for weapons and gunmen. [2] Residents holed up in their houses and apartments looked on amid bursts of gunfire as police dragged bodies into the street. By the end of the operation, which triggered a week-long state of emergency throughout Kingston, between 70 and 74 people, among them no fewer than 70 civilians, had been killed. [1] [2]

“Most cemeteries replace the illusion of life’s permanence with another illusion: the permanence of a name carved in stone. Not so May Pen Cemetery, in Kingston, Jamaica, where bodies are buried on top of bodies, weeds grow over the old markers, and time humbles even a rich man’s grave. The most forsaken burial places lie at the end of a dirt path that follows a fetid gully across two bridges and through an open meadow, far enough south to hear the white noise coming off the harbor and the highway. Fifty-two concrete posts are set into the earth in haphazard groups of two and three. Each bears a small disk of black metal and a stencilled number. The majority of these mark the unclaimed dead from the last days of May, 2010, when the police and the Army assaulted the neighborhood of Tivoli Gardens, in West Kingston. The rest mark the graves of paupers.” [2]

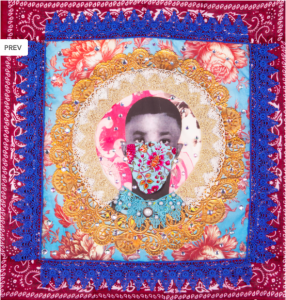

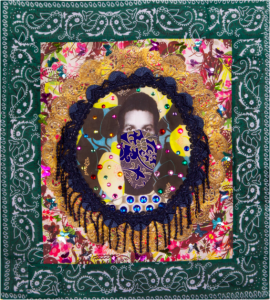

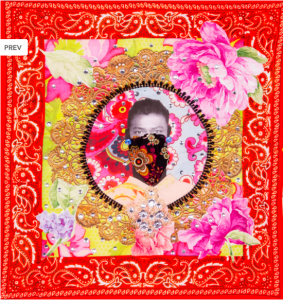

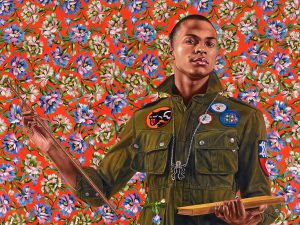

In the statement accompanying her Of 72 project, the artist Ebony G. Patterson asks, “What happens when seventy-two men and one woman die and no one knows who they are? Who were these men and this woman who were killed during the incursion of May 2010?” [3] Her work might be interpreted first and foremost as a reassertion of the lost personhood of these victims, haphazardly thrown into a mass grave, relegated to namelessness, with their families denied the closure of a proper burial. For weeks after the assault, residents of Tivoli were denied access to their loved ones’ bodies as the state dragged its feet administering autopsies; many were left to wonder if their missing loved ones were dead or alive. [4] A full year later, one woman was still trying to obtain an official death certificate from the government to organize a burial for her relative. [2] The government never released an official list of names of the victims. Patterson’s compositions, colorful squares of cloth decorated with multiple layers of ornamental patterns, might be seen as two-dimensional shrines for these unsung lost lives. The 73 individual pieces, each a different color and adorned with different motifs and accents, represent the individuality of each and every life lost in the carnage, allowing viewers to grasp its true breadth. Patterson’s aesthetic vocabulary resembles that of Kehinde Wiley, a Los-Angeles born visual artist whose works depict black figures (mostly volunteer subjects) in the style of historical portraits of noble European figures, with the addition of flamboyant, luxuriously colorful backgrounds patterned with floral motifs. These similarities point to the symbolic weight of decorative patterns and ornamentation in the work of contemporary Afro-American artists, especially as it relates to themes of reclamation of identity and representations of masculinity.

“Unofficially, some police officials characterized the operation as a “sacrifice,” pointing to a thirty per cent decline in Jamaica’s murder rate as justification for the loss of life in the Tivoli raid. An official from the P.N.P. suggested that Tivoli’s guilt was, in a sense, collective. “There was a torture chamber,” he said. “The community has to take some responsibility. I’m sure the entirety of Germany wasn’t guilty of the crimes of the Second World War, but an entire generation of Germans had to suffer the consequences of the Allied bombing.” [2]

Reporting on her blog about a March 2012 exposition of Patterson’s project at the University of the West Indies, Jamaican critic Annie Paul commented, “The 73 flags were suspended with clothespins from a simulated clothesline. You couldn’t help think…were the 73 hung out to dry by the Jamaican government?” [5] Indeed, much of the contention surrounding these seventy-something nameless deaths is rooted in the government’s continued lack of transparency and denial of responsibility regarding the operation, even as residents of Tivoli and outside entities alike have raised concerns of extrajudicial killings. Even before the incursion, in February 2010, a U.N. report had referenced “the propensity for extrajudicial killings by the J.C.F.” [2] Yet the government has continued to face this tremendous loss of life with impunity, perhaps because it stemmed from a totalizing narrative constructed by the government and its security forces themselves, painting Tivoli in broad strokes as a center from which criminality radiated throughout the community, one that needed to be systematically purged so that the entire community might recover its virtue and security.

“I heard so many horror stories,” he told me. “They summarily executed people. Do you know why? Because people outside hold this area in low esteem.” [2]

The theoretical framework of Trouillot’s “impossible history,” originally a means of explaining the historical contradictions of the Haitian Revolution, applies quite well to this narrative and Patterson’s response to it. Trouillot asserts that Enlightenment ideologies forced non-European groups to “enter into various philosophical, ideological, and practical schemes,” schemes which “recognized degrees of humanity” so as to avoid placing the dehumanizing realities of slavery in contradiction with the Enlightenment understanding of Manhood. [6] Trouillot’s retracing of how Renaissance and Enlightenment worldviews relegated black people to “the bottom of the human world,” designating them as the least human of human categories, and thus legitimizing the radical violences of slavery, might be seen to echo the assignment of Tivoli’s residents to a monolithic category of “deviant,” “criminal,” “detrimental to the community,” “enemy of order.” [6] If every person the security forces encounter in Tivoli is a member of this category which represents illegitimacy, deviance, and a menace to the law-abiding general public, then their extermination is legitimate on a symbolic level no matter the material threat they pose in the moment. And why should the government shoulder responsibility for these deaths legitimized by its intention to protect the public?

It is against these polarizing, flattening representations that Patterson’s art operates, resisting against the epistemological elimination of wrongdoing on the part of the state, blocking the construction of Tivoli’s own “impossible history.” As she told Paul in an interview, “It’s the least I can do as a concerned citizen, to kind of etch this episode into history, so that these people are not forgotten.” [5]

[1] Cordner et al. “The West Kingston/Tivoli Gardens Incursion in Kingston, Jamaica.” Academic Forensic Pathology, 2017 7(3): 390-414, 1 September 2017, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.23907/2017.034

[2] Schwartz, Mattathias. “A Massacre in Jamaica.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 11 Dec. 2011, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/12/12/a-massacre-in-jamaica.

[3] Patterson, Ebony G. The Of 72 Project, 2011, www.theof72project.com/project-text.php.

[4] Hall, Arthur. “Give Us Our Dead Boys, Say Residents.” Lead Stories | Jamaica Gleaner, Jamaica Gleaner, 1 June 2010, jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20100601/lead/lead2.html.

[5] Paul, Annie. “Ebony G. Patterson.” Active Voice, 17 Mar. 2012, anniepaul.net/tag/ebony-g-patterson/.

[6] Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. “Silencing the Past: Layers of Meaning in the Haitian Revolution.” Between History and Histories, 1997.

Images: Selected from the Of 72 Project (http://www.theof72project.com/images.php); detail from Anthony of Padua (2013) by Kehinde Wiley (https://www.artistaday.com/?p=2850)