Aditi Catalog Entry

In order to force one’s way out of invisibility one has to create a reason to be seen.” -Ebony G. Patterson

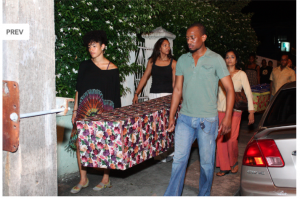

- Note: while I could not find images for the “Invisible Presence: Bling Memories” piece itself, I added an image from another performance piece Patterson created to illustrate what this must have looked like below.

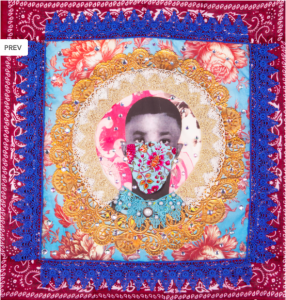

The “Of 72 Project” is a mixed media work on fabric, and Patterson uses digital imagery, embroidery, rhinestones, trimmings, bandanas, and floral appliques to create her pieces. Like many of her other works, the colors in the pieces are striking and viewers eyes are drawn to the various textures and colors that emerge within each portrait

As is the case with Patterson’s other works, the “Of 72 Project” aims to draw attention to the voices and stories of people who are otherwise overlooked in day-to-day life. In this particular project, she focuses on the victims of the Tivoli incursion in Kingston in May 2010. Each one of Patterson’s subjects has a colorful bandana that veils their mouth, thus obscuring a part of their faces. The contrast of the variety in colors and textures of the bandanas used and the monochromatic photograph of the subject serve to draw the viewer’s attention to the subjects’ mouth, and make the physical constraint that is applied to each subject all the more prominent. Thus, Patterson literally silences each one of her subjects, or indicates that they have been silenced, by physically constraining the use of their mouths, and leave the viewers to piece together the narratives of her subjects with only their eyes as a point of reference.

The of obscurity and anonymity of the subjects is consistent with the nature of the 72 victims of the Tivoli incursion themselves; news sources and government documents recording the event make it difficult to identify who the individuals were, and of the 72 victims, over fifty of them were buried in an unmarked grave. A large part of the narrative of these individuals that is then missing is knowing who they even were. Much like her “…when they were younger…” installation, the subjects used in Patterson’s piece are not necessarily faces of the victims themselves, but rather are faces that intend to evoke the emotions and images of people who could have fallen victim to the brutality. The fact that the bandana covers much of each subject’s face helps to evoke this sense, and allows Patterson to give a face to the faceless victims of the incursion, as it obscures the identities of her subjects’ enough to cast doubt as to who they truly are and Patterson is able to construct a possibility of a face, and a narrative for each one of her subjects

The use of color, and striking patterns in her work to interrupt the space of those who have a voice to insert the voices of those who do not is a common theme throughout Patterson’s other works. The idea of a bling funeral is a recurring one in her other pieces, like in “Invisible Presence: Bling Memories” and “Dead Treez”, and I believe is also emulated in the colors and textures of the “Of 72 Project”. In the creation of these vibrant, and dynamic images of the 72 victims of the Tivoli incursion, and in invoking themes of a bling (or dancehall) funeral in her work, Patterson is able to exact a different kind of revenge for the victims of the incursion by not only giving them the possibility of a narrative, but by also using their death as a way to interrupt the visible narratives that exist in the aftermaths of their deaths.

In order to see how the idea of bling (dancehall) funerals are evoked in Patterson’s work, and the impact of this, it is first important to understand what bling (dancehall) funerals are. In her paper “From the stage to the grave: Exploring celebrity funerals in dancehall culture”, Donna P. Hope explores the idea of bling funerals. She writes that bling funerals are

“preferred identity-rites that play a seminal role in the production and maintenance of celebrated dancehall identities which become standards of status and personhood for dancehall adherents and members of Jamaica’s underclasses. Bling/dancehall funerals are celebrations of life that combine media, material culture and the creative arts of music, fashion, dance and style. Using dancehall culture’s creativity and innovation that is concretized in this discussion on bling/dancehall funerals, Jamaica’s underclasses transgress the status quo by demonstrating their power and worth through collective living expression. The dancehall body resurrects and recreates these celebrated identities which operate beyond the grave as important standards in the maintenance of a spectrum of relevant and accessible identity-types for Jamaica’s underclasses. Bling/dancehall funerals operate socially and culturally as celebrated identity-spaces that offer preferred standards from which dancehall adherents select patterns of personhood, and simultaneously reap a sense of communal camaraderie and socio-political legitimacy on the dancehall stage and beyond. As a consequence, the stage is the grave and the grave is the stage” (Hope 266).

Hope describes the use of these funeral rites as a means to construct a different narrative for individuals even after their death, and as a means of sending a message to the rest of society to acknowledge these otherwise unacknowledged presences.

These concepts frequent many of Patterson’s works as she forces viewers to confront the voices and narratives of the silenced, like in her participatory performance piece “Invisible Presence: Bling Memories” she staged in 2014 during Jamaica’s Carnival. In this piece, Patterson interrupts the space of the visible, where the middle and upper classes celebrate Carnival on the streets of Jamaica. She uses the festival as a platform and the bling funeral as a gesture to insert and assert a moment of presence for those who do not have the agency to do so for themselves. In this piece, she parades brightly patterned coffins through the streets, and draws attention to the presence that could occupy the space inside; a presence that would usually go ignored in day-to-day life by most people; whether there is in fact a presence in the coffin is less relevant than the image of who the presence could be which is evoked in this piece.

Similarly, the actual identities of the victims she depicts in the “Of 72 Project” is less important than the ideas that are evoked in each portrait for the piece. The monochromatic nature of their faces could be indicative of the individuality, and the narratives, that were stripped from each of the victims following their death, and enable the viewers’ eyes to be more drawn to the brightly patterned background the subject is immersed in. It would be fair to describe these patterns, and these colors, as “loud” and they do indeed interrupt the space the viewer occupies enough to draw attention to images themselves. In an interview with the Huffington Post, Patterson has said “there’s this statement [Hope] made that’s always been with me, something like, ‘You may not have noticed me when I was alive but you’ll damn will notice me when I leave.’ Taking absolute control of how she wants to be seen, even in death, is such a powerful sentiment,” (Frank) and in her “Of 72 Project”, Hope’s sentiments are echoed as Patterson aims to construct an alternative narrative after death for the victims of the Tivoli Gardens incursion.

Works Cited

Hope, Donna P. “From the Stage to the Grave: Exploring Celebrity Funerals in Dancehall Culture.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 13, no. 3, 1 May 2010, pp. 254–270., doi:10.1177/136787790935973310.1177/1367877909359733.

Frank, Priscilla. “Jamaican Artist Explores How Fashion Can Become A Matter Of Survival.” The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 12 Nov. 2015, www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/ebony-patterson-dead-treez_us_564271c4e4b060377346c5fa