What is Patagonia Sin Represas?

A grassroots organization that pushed back against the Chilean government’s proposed HidroAysén Dam Project from 2007-2014.

What is HidroAysén?

The HidroAysén Dam Project was proposed when the Chilean government decided that (for the sakes of its affluent populations, and to further develop as a nation) it must double its energy capacity.

History of the Project:

- The project was created by Endesa in the 1950s, and in the 1970s, (with help from The Japan International Cooperation Agency) collected data to design the original project.

- The project proposed to build five hydroelectric dams over the course of ten years in the Aysén province, with the dams going from Cochrane to Santiago, and through the Pascua and Baker rivers.

- In 2006, Endesa and the Chilean utility, Colbún, proposed “HidroAysén.”

- The most recent HidroAysén project proposed will cost $7 billion “and many people believe that this project symbolizes just the beginning of Endesa’s plans for Patagonia’s countless rivers.”

Environmental Impacts of HidroAysén

#1) Forestry

The transmission line would create the world’s largest forestal clear cut, cutting through 5,720 hectares.

Photo: Outdoor Photographer

#2) Greenhouse Gases

Kristen Burrall’s unpublished MIT thesis, “Analysis of Proposed Hydroelectric Dams on the Río Baker in Chilean Patagonia,” calculates that the transmission line would also contribute to 70% of the project’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Photo: NRDC

#3) Flooding

The dams may cause severe floods (leading to property and livestock loss) when water behind dams reach capacity, resulting in downstream flooding.

Photo: Chron

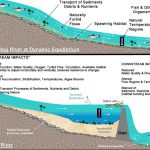

#4) Water Quality

Trapping river borne nutrients in the dams can lead to the growth of toxins, deteriorating coastal water quality, which would prove harmful to flora and fauna.

Photo: American Rivers

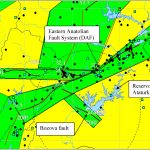

#5) Impact Seismically Active Regions

The dams will negatively impact seismically active regions.

Excessive water pressures in large reservoirs can trigger earthquakes.

Photo: InTechOpen

#6) Glacial Impact

The dams will increase glacial disaster risk, and these disasters would lead to livestock deaths and property damage.

Photo: Columbia

#7) Extinction

Large dams are one of the leading causes of extinction in aquatic ecosystems, because they lead to habitat degradation and less variation in water flow, which fish rely upon.

Photo: Nation Thailand

#8) Sustainability

The project also undermines principles of sustainable development. Dams are detriments to biodiversity, which is key to sustainability. According to civil engineer and University of Chile associate professor, Roberto Roman Latorre, solar and wind energy systems are sustainable- dams are not. The necessity of the HidroAysén purely does not make sense, when people are already investing in other forms of clean energy (such as solar and wind) that prove energy-efficient and sustainable. This especially holds true because Chile is home to the Atacama Desert, (one of the world’s best solar energy sources) which already has existing power lines and, according to experts, would provide as much energy as HidroAysén.

Photo: AZOCleanTech

#9) Photo: Geocaching

“‘HidroAysen didn't even consult with us; they showed up and gave us a relocation plan, as if they could kick us off our land before a decision was even made.’"

- 39-year-old wife and mother, Elizabeth Schindele, who lives near one of the proposed dam sites.

Transcribed:

In 1980, the Chilean Constitution declared that “[t]he rights of private citizens over waters, recognized or constituted in conformity with the law, shall grant proprietorship to the owners thereof.” This demonstrated that the Pinochet dictatorship intended to “insert free-market ideals into the realm of water rights.”

One year later, the 1981 Water Code was passed, and since then, the Chilean government has exercised little control over water disputes.. This code “transformed water into a private commodity, and invented a new type of water right to take advantage of the country’s potential hydroelectric resources.” However, the code says very little about water coordination or conflict resolution.

Originally, the Chilean state owned and distributed water, but following the Pinochet dictatorship, water rights were passed on to investors, and in 1997, a Spanish company bought the water company Endesa Chile, which became Endesa Spain, and has owned 80% of Chile’s nonconsumptive water rights. Endesa Spain was purchased by Enel (an Italian company), and has become one of the world’s largest energy suppliers.

The neoliberal logic present in 1981’s Water Code has led to water conflicts becoming a symbol of struggle. An example being the case of Alto Maipo in 2008. The Alto Maipo proposition was to construct a large hydropower project in the mountains above Santiago. The success of the Patagonia Sin Represas movement inspired resistance and social movements in Alto Maipo.

What’s interesting is that the actors involved in both Alto Maipo, and Patagonia Sin Represas, are primarily people who are not legally considered “water users” and have “thus traditionally been excluded from the realm of water governance.”

Transcribed:

It is pertinent to consider the impacts that neoliberalism had on Chile during the period of HidroAysén. Neoliberalism emerged in Chile when Augosto Pinochet rose to power in 1973, implemented it, and practically proclaimed that everything in Chile, including natural resources, was for sale. Neoliberalism serves as an extreme form of capitalism, in which the government believes that everything should be market driven. Neoliberal practices facilitated the privatization of water, as the sale of a natural resource such as water, is normally kept under state control. These sales led to northern companies buying up these southern resources.

Chile has served as a laboratory for extreme neoliberal reform, and despite the ending of the Pinochet dictatorship, it remains institutionalized.

Chile is perceived by scholars to be one of the world’s most neoliberal nations, and according to many activists, “the circumstances surrounding the approval of the HidroAysen project in 2011 demonstrated the gap between the rhetoric of environmental policy and the neoliberal economic model.”

Patagonia Sin Represas serves as a not only a push back against HidroAysén, but against Chile’s neoliberal state, as Aysén itself had long been neglected by the government in terms of infrastructure and resources.

Although it has facilitated economic growth, the environmental impacts that neoliberalism has had are far more profound. Neoliberal conservation encompasses the world of ecophilanthropy, which has led to exploitation, as public accountability has led to the privatizations of many Patagonian landscapes.

Patagonia Sin Represas is an organization that facilitated a major movement- the opposition of the proposed HidroAysén Dam Project. (Read more on the left.)

The project, made possible in part by the passage of the 1981 Water Code (additional information can be found under the “Water Code” tab), poses numerous environmental risks (outlined on the left), and politically, the environmental implications go against Chilean founding principles as its Constitution, “guarantees its citizens the right to live in an environment free from contamination and creates an affirmative obligation on the government of Chile to serve the environment.”

The Chilean government was willing to infringe upon these rights because it believed that more electricity needed to be generated. Patagonians questioned this belief, and knew that any benefits from the project would only aid the Northern Chile, as Chile has historically extracted natural resources from the south to allocate amongst northerners. Aysén communities would not receive energy from the dams at all, nor would their electricity rates be lowered.

The project would impact 64 communities, with many families being displaced. Social displacement would prove especially disheartening to the indigenous Mapuche population (depicted below), that had fought fiercely for their land for centuries.

Photo: Culture Trip

It would also be impossible to relocate entire communities of people, as there are no comparable ranch lands. As quoted at the top of the page, insufficient relocation plans were forced upon the residents of Aysén.

Additionally, the industrialization in Aysén that would need to occur to accommodate the dam workers would not only double the region’s population, but also greatly disrupt traditional ways of life.

2011 EIA

To combat opposition, HidroAysén attempted to save its image by recruiting scientists who would extol the necessity of the project’s completion. These scientists were enlisted to help begin HidroAysén’s 2011 EIA process that proved suspicious for reasons of: conflicts of interest, lack of certainty that the scientists hired were actually experts on the topics they wrote about, incongruities in data analysis, and a blurring of information. This led to Congressperson Gabriel Silber alerting the press that, “‘There have been many administrative irregularities and possibly wrongdoings during this [EIA] process. We think all kinds of pressure have been applied to break environmental institutions to approve the project….They have tried to do environmental fast track, tampering with reports and ignoring technical opinion.”

Outside scientists also complained that, “there [was] no real science behind the approval of HidroAysén.”

The Protests

It is pertinent to consider the impacts that neoliberalism had on Chile during the period of HidroAysén. (Historical context, and additional information included under the “Neoliberalism” tab.) Neoliberal practices led to environmental conservation in the region that was largely initiated by private efforts (eco philanthropy).

One such instance lies in Aysén itself, where “the conservation of the Chacabuco Valley [Valle Chacabuco] through philanthrocapitalism not only supports Chile’s neoliberal project but ensures its dynamic reproduction.” This area would be most directly affected by the proposed dams, and is where HidroAysén’s offices are located.

The wider issue of the construction of the dams lies in the fact that they implicate “the effects of neoliberal economic policies which not only privilege particular strategies of industrial development but also shape the ways in which ‘sustainability’ and ‘conservation’ are promoted and contested.” These developments are partially why Patagonia Sin Represas was not solely a social movement pushing back against HidroAysén, but against Chilean neoliberal order.

These movements began in the 1990s, when the Aysén Life Reserve (which presently serves as the backbone of Patagonia Sin Represas) was formed to fight for sustainable development. Since then, Patagonia Sin Represas has taken off, and the movement ensured that there was rural opposition to the Chilean State’s neoliberal agenda to pass HidroAysén. These oppositions came in waves of campaigns, councils, protests, and marches.

One of the first protests started with a single gaucho from Cochrane, who heard about HidroAysén’s plans, and decided to go to the capital to demand that the government stop the construction. As he passed each ranch on horseback, word spread, and within two days, hundreds of riders had joined him. These beginning marches led to a ripple effect of people vocalizing their concerns regarding HidroAysén.

In response to HidroAysén’s EIA, activists launched a campaign imploring state officials to “vote with their conscience,” and targeted the eleven officials who sit on the committee that votes on EIA projects. Also in response to the EIA, the Consejo de Defensa de la Patagonia Chilena (consisting of local ranchers, priests, lawyers, and nongovernmental organizations, as well as international organizations and celebrities such as: International Rivers, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (Natural Resource Defense Council), Yvon Chounard, and Douglas and Kris Tompkins) emerged. These efforts, combined with comments by Patricio Rodrigo, director of Patagonia Sin Represas, made on national television, were successful in leading to the advocacy of the EIA process becoming more technical.

In early 2012, a region-wide protest lasting several weeks was held. Leaders of the Aysén Social Movement demanded representatives from the Chilean State travel to Aysen to negotiate, and managed to obtain signatures on agreements for inter-regional dialogue. Since the Chilean government offers no authority over water disputes, the residents made sure that change occured on their own accord. Also in 2012, Aysén experienced a social movement that cut the region off from the country for three weeks and led Colbún, to withdraw its financial backing from HidroAysén, leading to new EIA reform efforts.

Patagonia Sin Represas eventually led to the largest demonstration since the late 1980’s demonstrations to end Pinochet’s dictatorship. Other protests include: the January 2011 protest to President Piñera at the Museum of Light, crowds gathering outside the EIA Agency’s Aysén Office, and 40,000 people marching in Santiago.

These efforts have inspired other social movements, such as the Alto Maipo movement (mentioned under the “Neoliberalism” tab.) Although the Alto Maipo conflict remains unresolved, the Council of Ministers revoked HidroAysén’s permit in June of 2014, and by 2017 it became clear that the project would not go through.

The successes of Sin Represas social movements also had other lasting impacts, and “across Latin America, social movements are contesting the social and environmental consequences of the neoliberal restructuring.”

Patagonia Sin Represas also sparked an environmental coalition in Argentina, and the HidroAysén case has served to illustrate “how efforts to deny the role politics plays in such decisions can weaken the legitimacy of EIAs.”

Most recently, the HidroAysén project has influenced Chile’s 2013 presidential election campaign, with candidates forced to answer pointed questions regarding their support or opposition for the project.

Photo 1: International Rivers; Photo 2: International Rivers; Photo 3: Tompkins Conservation; Photo 4: Patagonia; Photo 5: Global Voices; Photo 6: Conservacion Patagonica

“There are people in Santiago, or other cities… they don’t have the love for Patagonia. We have the love for Patagonia. It is really easy for Chile to have no other love for this land… but in reality we grew up here, and live here. A lot of times Patagonia is a place that they can sell… or give as a gift, as they have already done.”

Patagonian gaucho who working as a park ranger.

*translated from Spanish; Photo: 180 Degrees South

“The countryside is divided. People that are against it look down on people who are in favor.”

Enrique Romero (farmer from Cochrane)

*translated from Spanish; Photo: Patagonia Rising

“[Chileans] don’t talk about it because it is known as an issue that will [only] cause damage in Patagonia.”

Santiago Resident

*translated from Spanish; Photo: Patagonia Rising

Further Readings

“180° South.” IMDb. IMDb.com, January 22, 2011. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1407927/.

Aronofsky, Pearson, Royer, David, Marcus, Emily. “Chile’s Environmental Laws and the HidroAysen Northern Patagonia Dams Megaproject: How Is This Project Sustainable Development?” Denver Journal of International Law and Policy41, no. 4 (2013).

Barandiarán Javiera. Science and Environment in Chile: the Politics of Expert Advice in a Neoliberal Democracy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2018.

Borgias and Braun, Sophia and Yvonne L. and A. “Http://Ljournal.ru/Wp-Content/Uploads/2017/03/a-2017-023.Pdf,” 2017. https://doi.org/10.18411/a-2017-023.

Brady, Heather. “Native Community Fights to Defend Their Sacred River From Dam.” Mapuche Tribe Fights to Defend Sacred San Pedro River From Dam, July 27, 2018. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/2018/07/sacred-san-pedro-river-dam-mapuche-chile/.

Conservacion Patagonica News. Accessed April 27, 2020. http://www.conservacionpatagonica.org/blog/.

Edward, Ryan. Lecture. Aprill, 22, 2020.

Jones, Charmaine. “Ecophilanthropy, Neoliberal Conservation, and the …” Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42704990.

Marcos Mendoza, “The Patagonian Imaginary: Natural Resources and Global Capitalism at the Far End of the World,” Journal of Latin American Geography 16, no. 2 (2017)

Louder, Bosak, Elena, Keith. “What the Gringos Brought: Local Perspectives on a Private …” Accessed April 27, 2020. http://www.conservationandsociety.org/article.asp?issn=0972-4923;year=2019;volume=17;issue=2;spage=161;epage=172;aulast=Louder.

Murphy, Annie. “Chile’s HidroAysen Dam Project Provokes Mounting Anger.” BBC News. BBC, May 21, 2011. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-13445300.

“Patagonia Rising.” IMDb. IMDb.com, June 8, 2012. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1820592/.

“Patagonia Sin Represas.” International Rivers. Accessed April 14, 2020. https://www.internationalrivers.org/campaigns/patagonia-sin-represas.

¡SIN REPRESAS! Accessed April 14, 2020. http://www.sinrepresas.com/struggle.htm.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Amie Campos for taking the time to speak with me, and for offering additional readings.