The outdoor clothing company Patagonia Inc. has for years been regarded as a reliable, impactful brand which produces comfortable garments and recreational equipment. T-Shirts and water bottles stamped with the iconic purple tricolor logo are abundant in camping stores and the homes of extreme mountaineers, Cub Scouts, and retirees alike. Though the company does not trade publicly, it achieves great success: its founder has recently achieved billionaire status. Even in an online search, the brand’s online store and Mount Fitzroy illustrations far supersede the landscape which inspired them. The true Patagonia- one of vast prairies, rugged mountaintops, and beautiful stories, has become overshadowed by the consumerist giant that shares the same name.

What sets Patagonia Inc. apart from other brands, and what gives it the power to conquer geography itself?

Patagonia’s founder, Yvon Chouinard, fathered many unconventional policies which guide the company’s sentiments to this day. Through counterintuitive advertisements about conservation, misleading color schemes diminishing the beauty of the landscape, and a faulty sense of identity, the relationship between two Patagonias is a tumultuous one, and is only becoming more complex.

In order to understand the inspiration for Patagonia, it is essential to evaluate the upbringings of the company’s founder. Yvon Chouinard had been fond of mountaineering since a young age, when he began rock climbing with a falconry group in California. Chouinard eventually had a desire to make his own climbing equipment, specifically climbing pitons that were lighter and stronger than other products on the market. In the early stages of his business, Chouinard lived a nomadic lifestyle, only possessing bare necessities. He “sold gear from the back of his car” and nourished himself from “two cases of dented, canned cat tuna from a damaged-can outlet in San Francisco” supplemented by “oatmeal, potatoes and poached ground squirrel and porcupines”.

“If you want to understand the entrepreneur, study the juvenile delinquent. The delinquent is saying with his actions, ‘This sucks. I’m going to do my own thing.”

– Yvon Chouinard, Let My People Go Surfing

Chouinard’s background mimics that of other extreme outdoorsmen and adventurers. Below, Chouinard’s quote is compared to Gregory Crouch’s, an author and mountain climber. Try to guess who said what, then hover over the quote to see if your identification was correct.

Gregory Crouch

Who said this?

“The soul of alpinism is to travel light and fast through a dangerous landscape in pursuit of a personal star. That is ascent.”

Yvon Chouinard

Who said this?

“The goal of climbing big, dangerous mountains should be to attain some sort of spiritual and personal growth, but this won’t happen if you compromise away the entire process.”

Photos: Hiking and Climbing Adventures & Forbes

Evidently, Chouinard’s sentiments mirror those of other alpinists, and cement the company’s belonging into a group of genuine outdoors-folk. With such a distinct personality within the outdoor clothing industry, one would think that Patagonia customers would be a niche group of individuals; a rarity amongst the masses. After all, according to their Spring 2001 Catalog, the company sold, “uncommon clothes for uncommon people”. Tragically, this company piqued the interest of many others, and the brand found its way into the corporate world. People enjoyed the simplicity, comfort, and function of the Patagonia line, and began wearing vests as a layer on top of professional business attire.

This phenomenon became so popular that the look was unofficially known as the “Midtown Uniform” which has inspired Instagram mockery accounts in addition to Buzzfeed Trend Research. Companies in the finance industry had been distributing Patagonia apparel embroidered with the company’s logo, which was “the gold standard” in the corporate world and became known as “the Power Vest”. Chouinard predicted earlier to his colleagues that, “people buy Patagonia clothing—to show off”. When the trend began its course, he remarked, “we are very carefully controlling who our customers imagine our customers to be”. Thereafter, Patagonia changed its policy dictating who was eligible to have their brand embroidered on a jacket. Partnership was restricted to a “small collection of like-minded and brand aligned areas; outdoor sports that are relevant to the gear we design, regenerative organic farming, and environmental activism”. The company worked to crack down on their partnerships with corporations who are misaligned with Patagonia’s minimalist and conservation mentality, such as oil, drilling, and dam companies.

Undeniably, Patagonia’s consumer base has morphed greatly since the company’s founding. With Patagonia jackets and vests being a symbol of wealth, lifestyle, and a conversationalist political statement in the Western World, it is possible that more people buy the jacket as a status symbol, rather than as trekking apparel. Throughout the course of Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia, readers meet a vast array of people living in South Chile and Argentina. Each with their own background and motive, these collective stories bring life to the countryside, and shower it in uniqueness. Now, with consumers worldwide attaching themselves to a Patagonia “brandwagon”, the landscape seems more tangible than ever, and the brand seems more bland than ever.

“It’s everywhere.” While some were looking for alternatives to Patagonia, others were committed to “flying the flag.”

With this development, the wonder and mystery of Patagonia has been molded into a boring average. The company has strayed away from its original goal to create apparel for the outdoors-folk, and has succumbed to a business model where anyone can be free-spirited and adventurous for a one-time payment of $99. It seems even adventure and natural beauty themselves have become purchasable.

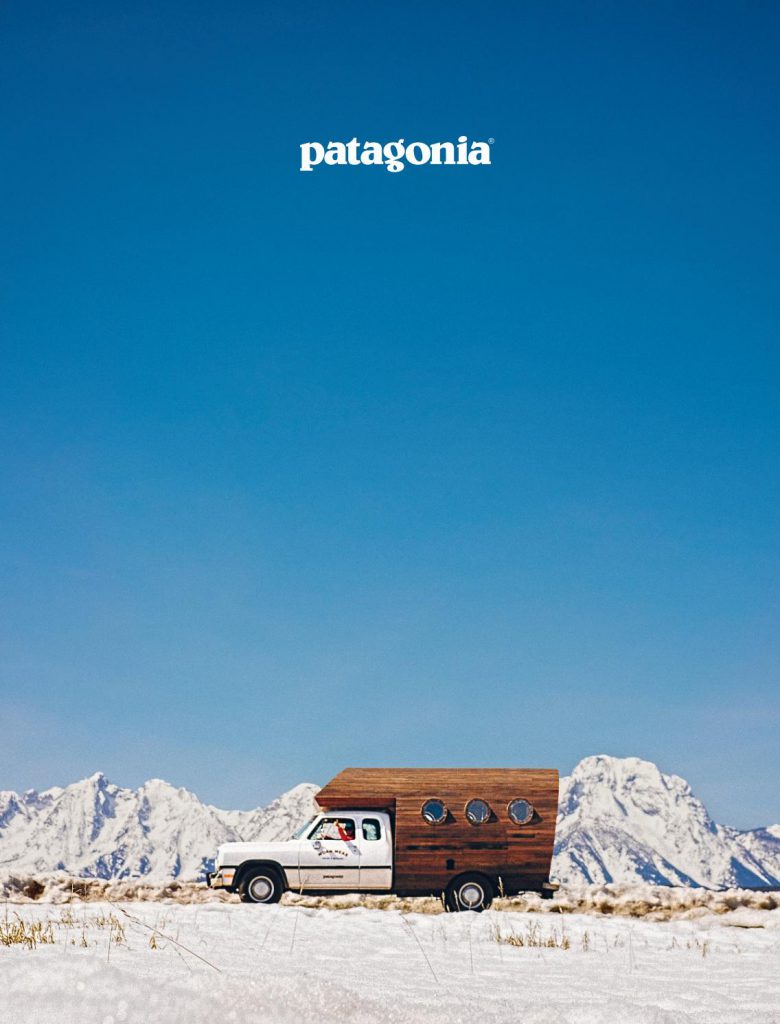

Patagonia’s landscapes are diverse, colorful, and almost mystical. No surprise, they make for great marketing material. Explore these images, which were cover pages for various Patagonia magazines.

All cover photos: Issuu.com

When asked to describe a magazine, most people mention the beautiful photographs which convey

“A boundless sense of nature and adventure… [and humans] a small detail in the face of immense nature.”

-Sharon Hepburn

For those who are indifferent about the style of their clothes, and instead need function from what they wear, Patagonia’s “granola look” perfectly fits this clientele. For these true outdoorsmen, the company’s simple aesthetic is appealing to the rustic folk.

“The hardest thing in the world is to simplify your life. It’s so easy to make it complex”

–Yvon Chouinard

According to the company website, Chouinard was inspired by Antoine de Saint Exupéry, a French aviator.

“In anything at all, perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to take away, when a body has been stripped down to its nakedness.”

–Antoine de Saint Exupéry

The “nakedness” and “granola look” are exactly what is imprinted across Patagonia jackets: muted colors, few exuberant patterns, and very traditional fits. This simplicity is ideal for genuine wilderness-goers, as it “projects to others in the know, an affinity with certain ideals, of lifestyle, linked with a vision of nature”. Chouinard believes the “genius of such products is that their very functionality makes them fashionable” and that he needed to make clothes “functional, tough, and simple- just as a good blacksmith would”.

Below is a look at Patagonia’s “granola” color scheme

Chouinard’s passion for conservation was sparked upon realizing that his debut blacksmith product, metallic pitons, had a downside. His creations were causing irreversible damage as they were hammered into and out of rock walls. Chouinard abandoned his pitons and develop aluminum chocks, which were insertable and removable by hand, and did not damage the wall. Producing these aluminum chocks was the origin of Patagonia Inc. and this early move towards reusability may have been the catalyst in creating a brand which places immense value in eco-friendliness and conservation.

Metal Pitons are inserted with a hammer and are permanently left in the wall

Aluminum Chocks can be added and removed by hand and are temporary

Today, these sentiments are prominently displayed throughout the brand’s publications. The activism page of Patagonia’s website reads, “We’re in business to save our home planet,” a vision statement drafted by Chouinard in 2018. This is a bold claim; the words overlaying a moving image of protestors with megaphones. Few other companies have such passionate preservation sentiments on their website. Patagonia was one of the earliest clothing companies to research the environmental repercussions of their products. They’ve prioritized materials that minimize environmental impacts. Below is a breakdown of their materials from 2017

Virgin Petroleum-Based Products

Recycled Materials

Cotton and Plant-Based Materials

Wool and Animal Products

Data from Patagonia Corporate Report 2017

Patagonia developed the site WornWear, which allows wearers to sell and buy used clothing. This slows consumption of new Patagonia gear and “keeps clothes out of landfills”. Research suggests that by extending the life of clothes by nine months, waste footprints can decrease by 20-30%. Whether inspired by Chouinard’s home mountains in California, or the splendor of the Patagonian landscape, the company has made a valiant effort to minimize their own footprint and promote conservation.

Video: Patagonia on Youtube

Data above from Patagonia Corporate Report 2017

Interestingly, promoting conservation through anti-consumption has a counteractive side effect. In the holiday months of 2011, Patagonia published an ad in the New York Times which contained a picture of their jacket, the words “Don’t Buy this Jacket” and information about reducing the consumption of new clothes. The company’s intent was for consumers to rethink their purchasing habits, so as not to buy more than they need.

Patagonia's Revenue

Data above from PrivCo

Some critics claimed the advertisement was an attempt to draw interest in the product. Their claim was supported by valid evidence: in the nine months following the ad campaign, the company’s sales increased by 30%. This may have been a societal oversight on Patagonia’s part, or it may demonstrate the consumer’s trust in the future Patagonia is building.

Patagonia is well-known for its environmental efforts.. [consumers trust] the company’s anti-consumption message.”

-Chanmi Hwang

Video: Our Changing Climate on Youtube

Because this anti-consumption advertisement actually increased the consumption of Patagonia’s products, Patagonia was forced to produce more waste as a result. Though customers may have been shifting towards Patagonia for products with a longer lifespan, this cannot be known for certain.

“While the product is made in an environmentally conscientious way, it is still a product being bought.”

–Sharon Hepburn

The movement nonetheless increases the consumption of natural resources, and generates additional harmful byproducts associated with manufacturing. Yet again, it seems Patagonia Inc. has a complex relationship with its own values and objectives. Though the company hopes to manufacture its products in an environmentally friendly way, the fact that it creates products which must be manufactured in the first place is enough for one to question whether there are any other ulterior motives at play.