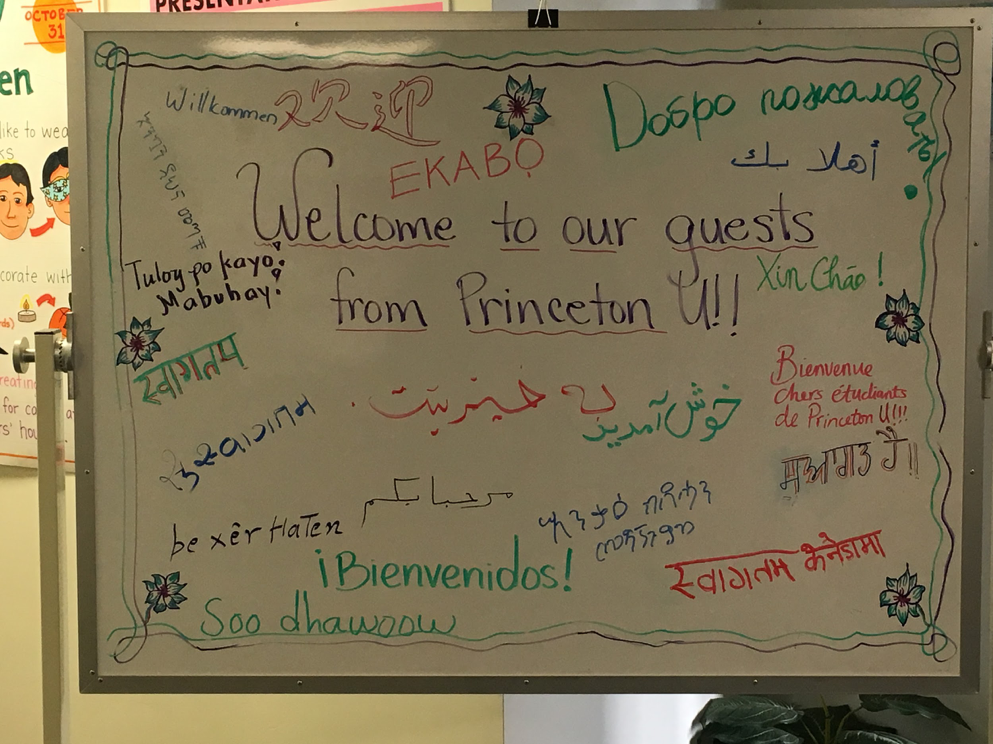

Welcome sign at Altered Minds

At Manitoba Interfaith, also called Welcome Place, the first thing our group did was sign a contract written in an unfamiliar language. Here’s how it unfolded. Minutes after our host, Marta Klaita, director of settlement services, introduced herself, a blonde woman in a suit entered the room. Without introductions, she handed us a contract that was written in a language none of us understood. There was only one full sentence on the page, and I had no idea what it said. Choosing which word to circle for my gender was like flipping a coin. I took an educated guess that “Data” meant the date. There were two dotted lines, presumably, for my signature. Deb Amos, our professor, wrote on one line and handed in her paper. The blonde woman handed back the form without so much as a smile.

We handed in our forms and marinated in a brief awkward silence before another staff member entered the space with a smile and an explanation. She told us this was intentionally designed to give us “a taste of being a refugee.” The blonde woman, Valentina, was a refugee who worked at Welcome Place, and the contract was written in Albanian. The other staff member noted that they would switch it up sometimes, bringing in big, gruff man to deliver the contracts instead. Valentina told us what we just contractually agreed to do:

“After your death, you’re signing to use your body parts for science.”

When I think of language, I usually think of culture or family. But the message was very clear here: knowing an official language like English gives you agency and security. I spent some time at Altered Minds afterwards, interviewing groups of people – through their translators – about the role of English in their resettlement. Most people had yet to take the Canadian Language Benchmark assessment. So I asked what their goals were – education, schooling, etc. – and how often they’d plan to speak English. Some planned for English literacy to be another tool of the trade – after work, they could return to their families and converse in the language that made them feel comfortable. Some would skip learning English altogether if it meant they could get a job more quickly. There were also a good deal of people who spoke to me in English.

But nearly everyone told me that learning English would help them learn Canada’s laws. Upon their arrival in the country, only a small group of them were taught the basics of Canadian law in their native language. Most newcomers didn’t get those basics – they couldn’t know just what they didn’t know about day-to-day life here. One woman had been in Canada for about 1.5 months. She never went anywhere without her interpreter.

Everyone should have a right to know what’s going on. When an interviewee asked me (in English) what I planned to do with this interview, I told him I wanted to make more people aware of just how tough it is to balance language with raising children, working, or going to school. But it already seems like a no-brainer, and honestly, reading and writing this post in English almost feels like it doesn’t do the experience justice. Welcome Place really got it right with that first exercise, though I wasn’t worrying about my future when I walked in there.