Your Delivery is Here

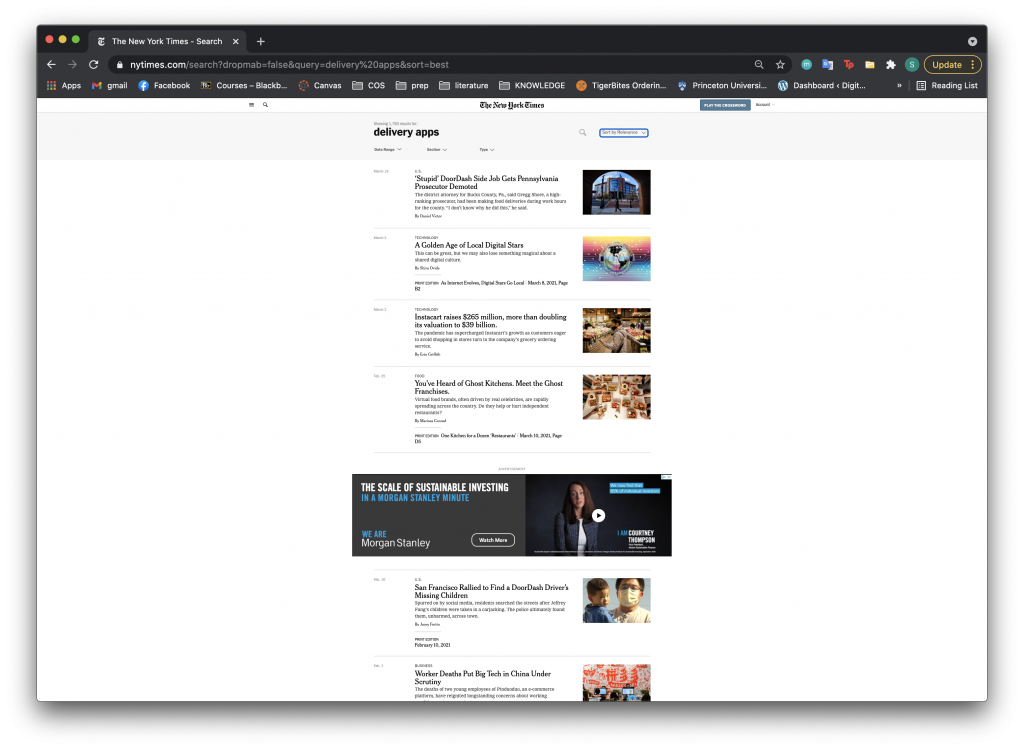

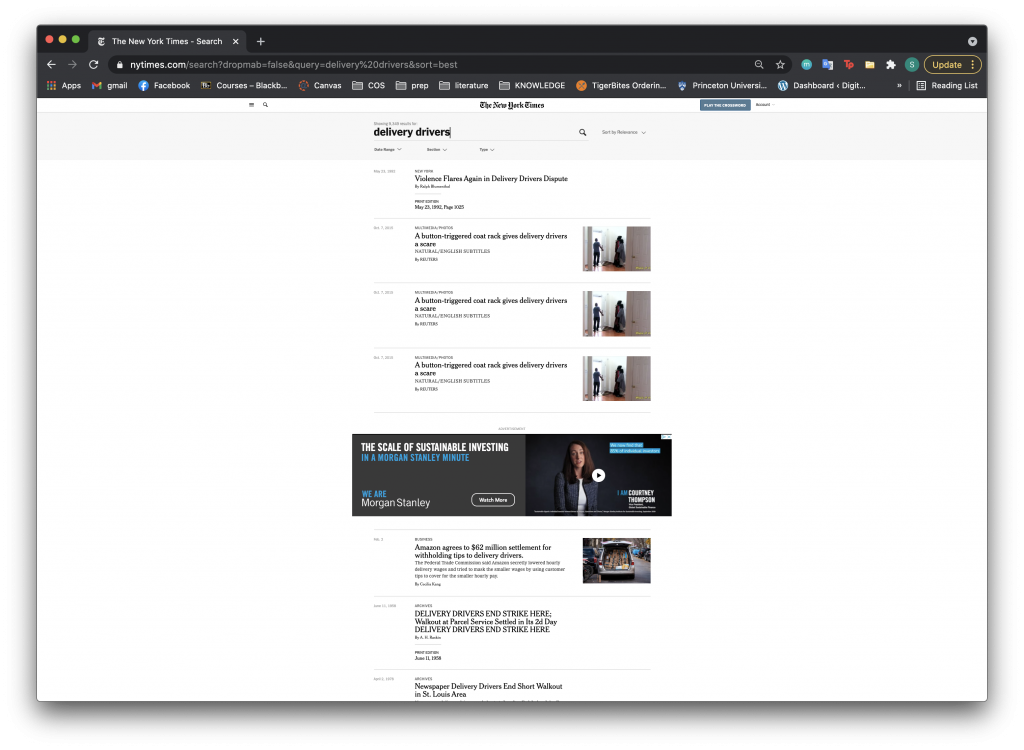

When I started this project, I envisioned two competing narratives – restaurants and technology. I knew that the relationship between the two would not be black and white and that there would be different perspectives that I would encounter, but I did not account for a third very crucial piece to this story, the delivery drivers. In retrospect, my initial lack of attention to delivery drivers was in part influenced by the absence of these narratives in the media. For example, when searching through The New York Times’ articles archive, the query of “delivery apps” produces far more relevant and informative articles than “delivery drivers.” In addition, I had entered the story from the restaurant point of view and I was under the impression that delivery drivers were synonymous with the big technology companies they work for. They are not.

There is no stereotypical delivery driver. Drivers come from all different cultural, socioeconomic, geographical, and educational backgrounds. Some people see delivering as a side gig while others rely on it as their main source of income. While delivery drivers do not constitute one homogenous group, this does not mean that their voices should not be heard or represented. In fact, the diversity that exists within the delivery driver community warrants greater attention since it is the product of different cultural and economic forces. The roles of food delivery drivers are also products of the gig economy, which is based on an online platform that connects clients to workers who usually work flexible, temporary, or freelance jobs. As the gig economy continues to permeate into spaces beyond car sharing or food delivery, new groups of delivery workers, similar to the current food delivery drivers, will emerge. I wish I had more time to trace out the history of delivery workers and drivers because these roles predate the advent of food delivery apps, but this brief introduction will highlight recent events involving delivery workers in the Bay Area.

In November 2020, California voters approved Proposition 22, a measure that allows gig economy companies to continue treating their drivers as independent contractors. Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash created the measure so that they would not be forced to employ drivers and pay for health care, unemployment insurance, and other benefits. The three companies spent over $200 million, making the ballot measure the most expensive in California’s history, and bombarded users of their apps with slogans like “A no vote would mean far fewer jobs” (Conger). Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash claim that keeping their drivers as independent contractors will allow the implementation of more flexible and proportional benefits structures. However, labor unions and local leaders believe that Prop 22 will harm drivers who already have been disadvantaged during the pandemic.

Talking with my fellow California friends in the fall, I realized that many people were not clear about what a “yes” vote for Prop 22 actually meant. One friend thought that a “yes” vote meant supporting the delivery workers. Another friend believed that car-sharing rides and delivery fees on these company’s online platforms would increase if the companies were forced to treat their drivers as employees. The lack of solid information around Prop 22 is surprising given the measure’s repercussions. The passage of Prop 22 is a win for Big Tech and a signal that these gig economy companies have the financial and political strength to push through legislation that favors their business models. These companies are likely to try to enact similar measures across the country, which will only continue to sideline delivery workers and keep them out of the conversation.

Meet the Dashers

David Miller writes that “the rise of what is called the ‘gig’ economy, digital technologies, such as smartphone apps, have blurred the boundaries and responsibilities of companies in relation to workers” (Miller, 4). Delivery app companies and the drivers that work for them constitute one of these relationships where digital technology is rapidly transforming interactions and ways of working. The story would not be complete without hearing the perspectives of these delivery workers, who are often not given the space to share their narratives.

“The rise of what is called the ‘gig’ economy, digital technologies, such as smartphone apps, have blurred the boundaries and responsibilities of companies in relation to workers.”

During the months of December 2020 and January 2021, I tried to engage with DoorDash drivers, also known as Dashers. I did not want to interrupt these drivers’ work or bait them into interviews so during non-peak hours I went to areas around the Bay Area where I had seen Dashers congregate. I spent time around Telegraph Avenue in Oakland and tried to approach Dashers who were waiting around for their orders to be prepared. I was anxious to approach these drivers because I did not want to distract them from work and given COVID-19 social distancing protocols, I was unsure if people would be comfortable being interviewed. I was able to interact with a handful of Dashers but none of them wanted to be formally interviewed and some of them did not want to engage at all. One driver gave me a cellphone number so that I could call him after his work, but the number turned out to be made up and I was left listening to a beeping sound coming from the other end of the line.

I realize that the troubles I had encountered while trying to talk to Dashers can be seen as byproducts of the tensions between delivery drivers and other shareholders. Given the recent passage of Prop 22, the media’s lack of coverage on gig economy workers’ perspectives, and the fragile dynamic between drivers and restaurants, it makes sense that Dashers are reluctant to speak about their work and their attitudes towards the companies and restaurants they exist between. These drivers are caught between Big Tech, with their money and growing political clout, and restaurants, who are backed by community support, and it is understandable that they would be weary of an outsider who approaches them.

These drivers also work in temporary and mostly anonymous conditions, where deliveries end when the food is dropped off at an address and full names are never disclosed. Asking a driver to engage in an interview is to ask them to interact in an environment that is more visible and direct and is different from the one they work in. While I wish that I could have talked with Dashers about their experiences and their perspectives, I now realize that the absence of their direct voices does not mean that their stories do not exist. My inability to recruit interlocutors reflects the precarious position that these delivery drivers are in — working in a nascent economy that still has not clearly defined or acknowledged their roles.

Automobiles, Auto-ethnographies

Since I ran into a roadblock trying to engage with delivery workers, I decided to try “dashing” myself. While auto-ethnography is a common ethnographic practice, I was initially conflicted about signing up to become a Dasher because unlike many drivers, I do not need the job to support myself financially. In addition, the money that I made would benefit the Big Tech companies and contribute to a system that often hurts local restaurants. I was aware that my position as an educated upper middle class adult prohibits me from truly understanding the experience of many other DoorDash drivers. With these biases in mind and committing to donating the money I made from deliveries back to local restaurants, I ended up signing up to be a DoorDash Driver on December 4, 2020. I was surprised by how easy it was to sign up — an automated background check, a bank account, a driver’s license, basic contact information, and I was approved to start delivering orders by the end of the day.

I dashed on two separate occasions — the evening of Tuesday, December 15 and midday Friday, December 18. Accompanied by a friend, I would drive around the East Bay in search of deliveries. One of the biggest surprises about the DoorDash Dasher app was how it integrated directions, payment, contacting customers, and other aspects of delivery into one platform. At the same time, the algorithm that matched deliveries with drivers and the payment calculation methodology were unclear. During my first delivery at Safeway (a surprising location because Safeway is not a restaurant but a grocery store), I started talking, off the record, to another Dasher waiting for his order and he mentioned that after over two years of dashing, he still did not understand the algorithms. The discrepancies in the platform were highlighted by the fact that we both had to wait over 20 minutes because DoorDash had allowed users to place orders at Safeway even though the service desk that handles these orders had already closed.

On Tuesday, I made $11.50 from 2 deliveries over a total of 1.2 hours, which is well below California’s minimum wage.

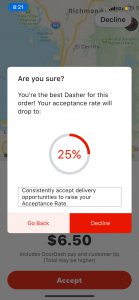

Another unclear aspect of the platform was how declining deliveries affected my rating as a driver. There were three deliveries that I ended up declining because they required driving to Albany, which was more than 20 minutes away from where the restaurants were located. Each time I declined the order, the platform would try to persuade me not to, asking “Are you sure?” and mentioning my “Acceptance Rate.” According to the DoorDash website, a lower Acceptance Rate comes from declining delivery opportunities and it “negatively impacts the experience for other Dashers, the customer, and even the merchant” (DoorDash Dasher Support). Acceptance Rates, along with Customer Ratings, Competition Rates, and On-time/Early Rates, are used to help DoorDash track Dasher performance. While these data points can help DoorDash objectively evaluate Dashers and find ways to optimize their platform, they do not fully capture all the aspects that factor into a delivery. For people who have limited gas or time, some deliveries may be infeasible and might actually cause the delivery driver to lose money. I was lucky enough to not have tight gas restraints, but I know that many drivers do. Gas and other constraints heavily influence a driver’s decision to accept an order and current DoorDash statistics are built around the simplistic idea that all deliveries are good deliveries.

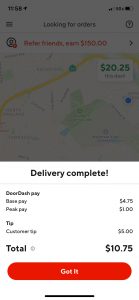

On Tuesday, I made $11.50 from two deliveries over a total of 1.2 hours, which is well below California’s minimum wage. I later learned from a DoorDash driver (off-the record again) that Tuesdays are the worst days for deliveries. Even though I picked a bad day to dash, I realized that DoorDash driving is not as easy, nor as lucrative, as many people imagine. From my Friday lunch period deliveries, I was able to make more, earning $32.39 from three deliveries over a total of 1.4 hours.

However, I soon realized that most of my earnings came from customer tips and that the pay that was advertised with the delivery already included the customer tip. Two of my Friday deliveries from MIXT, a high-end salad shop, were advertised at $10.75, but $5 of this pay came from the customer tip. It shocked me that “tips” were not actually tips added after the original delivery but in fact advertised as part of the initial payment. While DoorDash apparently ended its tipping policy that used tips to subsidize its payments in July 2019, my experience accepting DoorDash payments seems to suggest that there still exists opaque payment practices within the DoorDash system (de Freytas-Tamura). I can only speak from my limited experience as a Dasher, but the payment calculations did not seem to add up and left me wondering how sustainable DoorDash driving truly is.

Although I wish that I could have talked to real DoorDash drivers with more experience driving around the Bay Area, from my experiences dashing, I did gain a new perspective on the role of delivery workers. My previous interactions with Dashers had mostly revolved around seeing them impatiently harass restaurants for their orders, holding up their DoorDash apps in the faces of restaurant workers. However, I now realize that these drivers are caught between powerful stakeholders — the customers, the restaurants, and the tech companies. When deliveries go wrong, Dashers are the ones who are blamed. Even though my livelihood did not depend on the success of delivering orders, I did feel anxiety and urgency when I drove around on delivery trips, dealing with the delivery deadlines, gas concerns, directions, and trying to plan ahead for the next order. I also had help from my friends and could not imagine navigating around new neighborhoods, accepting/declining orders, and driving all by myself. Dashers and other delivery drivers exist in transit, driving around for the purpose of others, but just because they take on nontraditional roles, does not mean that their stories do not exist. I hope that more can be done to share the perspectives of delivery drivers and to uncover more ways in which these drivers are constrained by the platforms and companies they work for.