Access full survey pdf here.

Access previous years’ surveys pdf (2013-2018) here.

Other survey data for diversity here.

Topics in Global Race and Ethnicity (AAS 303)

The archive is first the law of what can be said, the system that governs the appearance of statements as unique events. But the archive is also that which determines that all these things said do not accumulate endlessly in an amorphous mass, nor are they inscribed in an unbroken linearity, nor do they disappear at the mercy of chance external accidents; but they are grouped together in distinct figures, composed together in accordance with multiple relations, maintained or blurred in accordance with specific regularities; that which determines that they do not withdraw at the same pace in time, but shine, as it were, like stars, some that seem close to us shining brightly from far off, while others that are in fact close to us are already growing pale. —Michel Foucault

Given the prevalence of extreme amounts of data in the digitization and technology of our modern day and age, I attempt to be selective in order that our records of recent historical events don’t “accumulate endlessly in an amorphous mass”. In this “archive of the present”, I selectively choose artifacts of three separate but related movements to highlight the radicalism of social activism in the decade of 2010.

Through the lens of the internet one might be awash with information so much so that it drowns out these radical black protest movements. We may see unending coverage black celebrities, twitter feeds of our favorite media feeds, the first US black president, and an overarching image presenting black communities fully integrating themselves into the landscape of mainstream definitions of “success”. In this lens it might appear that any radical protest movements such as the 1960’s and 1970’s are a thing of the past.

I chose reform for higher education to suggest a continued radicalism about race, the effects of colonialism, and social concerns, up through the present day. These activists show that the racial concerns of the 2010’s go beyond celebrity, on-trend presumptions about success, and instead continues to address divisive and uncomfortable issues about race that remain matters of national and global importance. By highlighting activist acts and effects in the realm of higher education, I attempt to show 2010’s are still a decade of protest not so unlike other historical decades.

Black Panther is an engaging film of the futuristic African country Wakanda, covertly hidden from the rest of the world, that grapples with diplomatic questions of protectionism and secrecy despite its ability to share its highly advanced technological achievements to intervene in the many real and troubling crises facing the modern world we live in. It is a film that is presented in a lighthearted and comfortable way but actually delves into deeper spiritual, ethical, and geopolitical themes which challenge the viewer to rethink the political and social statuses and status quos of our modernity.

The premise of the film, an African nation with secret superpowers, unknown to the world but envied by the few who know, itself generated a certain excitement for politically engaged viewers and many members of the black community. Psychologically, it offers a counter-narrative to the narrative we are inadvertently pummeled with daily, a symbolism of Africa and persons of African descent as under-developed, as the ones in need of help or hand-outs from the rest of the world; rather, the world is in need of Wakanda. Even if just a movie, the power in the imagination to present pride, dignity, and empowerment of a country in Africa planning to lead others and set the stage on their terms rather than on a European-normative mainstream seems inspiring and even exciting, a way to break out of status quo in a lighthearted but nevertheless meaningful way, if only for the two hours of an imaginary film based upon a comic book.

Wakanda is set as a futuristic scientifically-advanced nation in contrast to the everyday modern world we live in rife with problems, highlighted early on as the plot zooms in to a small child growing up in poverty in Oakland, California, presented to us first on an instantly-relatable basketball hoop, as an instantly-relatable young child. Before we know it, the viewer sees as tragedy strikes his life. He loses his father at a young age and grows up with a resentment of those who killed his father, a mission to conquer the world using the resources of Wakanda, and has a name proportional to his hatred, calling himself Killmonger. His hatred of Wakanda stems from his father’s mission to end Wakanda’s isolationism and share its resources with the desperately-needing world, which he of all people relates to during his tragic and turbulent childhood. But his hatred also derives from his eventual knowledge that his father was killed by the former king of Wakanda, King Tchaka, who in a terrible moral and personal dilemma makes the decision in an attempt to save another Wakandan’s life.

Killmonger opposes Wakanda’s geopolitical choice of isolationism and wants it to share its assistance with the world. This resonates with dilemmas of the US and other nations to provide assistance, relief, education, and infrastructure to less developed nations. According to the film, one of the main ways Wakanda would be able to help the broken world around them would be to help share its technology. The image of a African nation as the provider and leader is inspiring and exciting, in contrast to being a land in need, it is the rest of the world in need of the powers of Africa. However, there is an eerie resonance, about what exactly it is Africa has to offer the world, when we see that one of Wakanda’s unique offerings is Vibranium, a unique “natural resounce” found nowhere else in the world. It is this near-magically powerful metal, given in a mythic ancient act to the five tribes of Wakanda, that is what allowed their society to develop so far beyond other nations and create their many social and intellectual advancements: a society, to a large extent, devoid of fighting due to the peace, afforded presumably due to the plenitude; and intellectual and scientific advancements from, presumably, the stability of society to devote time and resources to progression of knowledge. This resource Vibranium, being kept carefully hidden from outsiders, resonates eerily with the historical view of Africa and other less developed nations of the 18th and 19th centuries as places that did offer something to contribute to the world around them: resources*. During this era, less militarily and technologically developed nations around the world were colonized and exploited for natural resources such as “metals” that allowed colonizing powers to develop greater technology, military strength, and economic prowess, to further dominate other nations and outcompete each other.

Killmonger is the villain of the story, and he is determined to gain the Wakandan Vibranium and their military and technology to conquer the world. He states his goal to “liberate” and rescue the world, and presumably his goal is to continue his father’s mission. However, his actions tell a different story. He has an extremely simplistic and in fact odd approach, where he doesn’t question his plan of violence and conflict at any point with even the smallest amount of self-reflection. He never wonders if he could simply talk to the Wakandans about his difference in ideology; gain their favor by impressing them with his abilities; or try and resolve the cause of his father’s death. Instead he incipiently attempts to defeat the current King Tchalla in hand to hand combat and shows no mercy, no interest in knowing his close relative, no interest in knowing the people or culture of Wakanda to see what he thinks of them, before immediately challenging him to the death. This seems implausible to someone whose overarching goal is liberation.

In contrast to the other vibrant, interesting, and dynamic personalities, I find his character very undeveloped and we are offered no insight into his one-sided psychology of hatefulness except perhaps the over simplistic reason that his father was killed. This fails to illuminate any of the complexities we see in real world politics and why certain political actors profess military force as the most correct, or at least, purportedly the most “realistic” way of engaging with and impacting the world.

Killmonger seems like a paper character with no depth behind him. He has scars on his body marking every person he has killed. He seems simplistic like a cartoon. This serves its role given this is a superhero movie, a caricature; yet, does this simplistic model suggest something else? The level of simplicity apparent when Killmonger assumes his “purpose” to gain the throne of Wakanda, to depose the Wakandan king, to lead Wakanda to takeover the world seems implausible. Yet, perhaps this is intended to emphasize the overarching assumptions of viewers of the film, as Americans, as individual citizen global actors, or as political leaders.

Are there certain narratives we, too, take for granted? Are we limited in the way we see our roles in global geopolitics, or in our own homes? Do we lack imagination to seek alternatives, and simply work for progress within the limitations of the systems pre-existent and easily available to us? Maybe Killmongers oversimplification helps us become self-aware of our own prejudices, and question what psychological factors may have led to our perceived obstacles in the ways we conceive of global and local issues like conflict, hierarchy, power, and poverty.

Nevertheless, the oversimplified character Killmonger is part of the simplistic narratives of hero and villain portrayed not only in cartoons, but also in Hollywood, and serves to distort and undercomplicate geopolitics and interpersonal interhuman complexities. Conflict is not simple; humans are not one-sided. And political actors are not Killmongers: most of them have complex reasons, if not self-interest and personal gain, which certainly play a role, the complexity of political leaders to approach difficult questions and come to a correct approach is not conveyed in the simplistic Hollywood villain. Our real-world villains are not as easy to point out.

I also feel that it glorifies intelligence and respectability as defined by technology, power, and reverence for all things bright and shiny. Indeed, I find it hard to imagine how a blockbuster movie, perhaps, could avoid doing such a thing: this is part of the bells and whistles, the activity on screen. In addition, the setting is supposed to be science fiction and futuristic, and it is hard for futuristic sci-fi type genre to not inadvertently glorify technology, since a huge part of the narrative is attempting to capture this futuristic sci-fi world. Thus the film will certainly want to wow the viewers with shiny images of faster, bigger, technologies. Nevertheless, does this reify American meritocracy, the imagined availability of goods to all, due to trickle-down, everyone having an “equal chance” to the goods of society, and promises of access that are never fulfilled? The idealization of technology is part of what allows America to deny its problems because it purports to make up for problems with material gains that are so bright and shiny they appear universal and accessible to all. Everyone can feel a “part of” society because everyone in America can have an iPhone no matter who you are, but in the bigger picture we still have failed to offer equal access to the goods of society. This idealization prevents people from questioning their ostracization in society when they are offered the promise of American idealism, and these excuses are what allow narrative to continue for American exceptionalism.

In addition, this film equates technology with progress. The Wakandan technology is what Wakanda wants to offer to share with the world. While it is difficult to not equate technology and material advancement with progress, especially in the context of abject poverty both in the way it was pictured in the US with the film’s characfters in Oakland, as well as the film’s coverage of African poverty, it is a nevertheless a mistake to equate material progress with all progress. This film did glorify technology in such a way, not only in its text but also in its subtext. The overarching theme (the text) of the film could not be changed without changing the entire plot: a glorification of an African country for being the most developed country, not just socially and educationally but also in terms of military and technology. How else could the movie show a military showdown between good and evil without this text? In addition the subtext is in the characters conversations about the reason Wakanda is different from other nations. They explain it is not due to genius or something inherent about the Wakandan people, just due to technology. This glorifies technology: or does it? Or perhaps, does it take a subtle jab at the dominance of certain nations over others in our real world today?

*obviously, and also for labor depending on the nation

A global black solidarity to fight for a world free of hate crimes and racially motivated violence has been one of the driving forces of black diasporic collaboration from the beginning. Seeds of black diasporic consciousness were sown as early on as days of slavery, the first and most large-scale attack of violence on black bodies and black freedom, and the largest scale mass enslavement of a race of people, in the history of the world.

Violence has been just one, but unfortunately, a prominent one, of the persistent themes in the development of the black global consciousness and black freedom struggle. Despite black consciousness and disapora encompassing the depth of the positive self-understandings of an identity, such as ethnic and cultural celebrations, and historical and artistic investigations of one’s ancestry, almost any group as part of it’s self-understanding includes a component of shared struggle.

In the history of shared struggle against violence and racial hatred, the black political movement for essential rights has been fraught with compromise when ideals have come to head against real political and economic forces. Black global consciousness has meant a fight not only for racial equality for people of African descent, but for basic human rights for all people regardless of race. But these movements were often put to a halt when faced against political incentives of the people in power. In post-WWI treaties in Paris in 1919, the Japanese Empire which had had extensive contact with representatives from US Civil Rights organizations , proposed a “racial equality bill” at the meeting to found Wilson’s League of Nations. This was rejected because it was not politically profitable to the politicians who were most influential at the Paris Peace Conference.

Similarly, many victims of hate crimes go unreported because their cases lack conclusive evidence, and their stories are not compelling enough for the media. This was not the case, however, with Jussie Smollet. His case was picture perfect. He was a famous black gay actor. He was popular in his show Empire. And the alleged attack was not inconclusively racially related, or conducted by someone who may have had underlying mental health issues along with secondary racist tendencies. Rather it appeared to be premeditated, as he had received a threatening letter a week earlier. Finally, not only was Smollet a celebrity, but most importantly, he was a sympathetic victim: just as Treyvon Martin was chosen by the media due to his youth and innocence, people who are legitimate victims of hate crimes but do not fit a model citizen (for example, they may themselves have a criminal record, or simply be less successful in social status) or attractive young person are often ignored.

As a result of celebrity status and political connections, the Chicago prosecutor’s office has dropped charges for Smollet despite interviews saying they believe he is guilty. The case is now closed, and only so much information can be deciphered from what has been reported. This timeline attempts to show a guide to elucidate the potential political influences that led to an unprecedented dropping of charges for Smollet.

True victims of hate crimes lose credibility as a result of political maneuverings behind the scenes to afford special privileges to celebrities like Jussie Smollet. As a result of his political ties, his actions are overlooked by the very people in power who claim to be advocating for rights of people who are oppressed due to racism. As usual, the grassroots struggle for black rights is jeopardized by political interests.

https://cdn.knightlab.com/libs/timeline3/latest/embed/index.html?source=1ehTNuv_3W8jDF8XL6Wq-Za2OI59j_P-3yXo_MMUiumU&font=Default&lang=en&initial_zoom=2&height=650

I chose to use a timeline to keep track of the various forms of evidence and understand the political ties. I thought the timeline would help keep the many disparate facts from various news organizations clear in order to form a picture of the likelihood that political influence did or did not play a part in Smollet’s apparent special treatment in this case. In particular, news of contact from political influencers to the prosecution was learned later on but actually occurred before the police suspected (at least officially) Smollett which was something I wondered before I had put it in a timeline. Aside from that one fact, I realized there weren’t that many interesting facts to the case so my timeline was not as helpful as I had hoped.

Sources

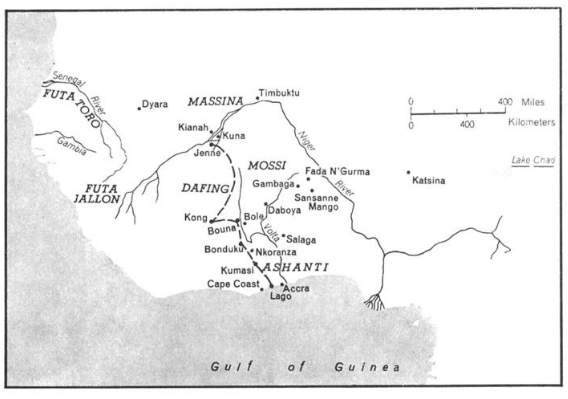

After reading Freedom Papers by Rebecca Scott and Jean Hebrard, I began researching biographies of other West Africans who were captured and brought to the Caribbean also around the turn of the (19th) century. One interesting figure came up that had many similarities. Abu Bakr al-Siddiq was, like Rosalie, captured from Western Africa as a young person, around the age of 14, and may have had a similar experience in several respects. You can see her region of Futa Turo farther west between the Senegal and Gambia Rivers, which you can compare to his birthplace and travels over land from Timbuku to Ashanti.

Map (Source)

Bakr was captured several years after Rosalie, however, and transported on an English slave ship in 1804, just 3 years prior to Parliament’s 1807 abolition of slave trade.

In contrast to Rosalie, Bakr’s movements are much more documented, since the record we have for him comes from a self written autobiography. For the historian, the record available is much less fragmented and more continuous. In addition his life story was less fragmented and more continuous, as he remained on the one island, Jamaica, until the time he was legally freed in Britain’s 1833 Emancipaion Act. He did, however, have many travels in Africa both before his capture and later after his legal emancipation.

Bakr’s autobiography was translated into English from his original writing in Arabic; first himself in 1834, and then professionally translated in 1835. (During his time as a slave in the “New World” he learned to speak English but he wrote only in his native Arabic, so his own verbal translation was recorded by a scribe).

You can access the full text in English of his own autobiography online here (begin at page 157). Prior to this text is a summary of his biography by modern historian Ivor Wilks (p. 152-157).

Childhood

Abu Bakr al-Siddiq was born in Timbuktu around 1790. (Curtin, 157) His father was named Kara Musa (157), and mother was named Hafsa (159). He spent his early life in Jenne (153,165), and much of his education in Buona (165).

Map (Source)

At age 9, after the death of his father, his tutor first considered arranging for him to a pilgrimage (hajj), and then instead brought him on a long journey to Buona, after learning of master educators there. Considering the number of miles from Timbuktu to Buona, and the speed of travel with animals or on foot, one can imagine this trip was broken up into small segments. This was typical of travel in this time period. For example, an essential Muslim sacrament is the pilgrimage to Mecca. That trip was one which was very typically broken up into many small trips over many years of one’s life.

In Bakr’s own incredible story of travel, in his case, for the sake of his education: “before reaching the age of nine, he had traveled with his tutor more than 600 miles. Then he spent a year in Kong, and went to Bouna for further education.” (Source) “In all these places, he had relatives and in-laws. One historian “remarked humorously that belonging to Islam was like belonging to a touring club” (Goody 1968:240, quoted here )

The Ashanti province ,where Buona was located, had faced civil and political upheaval in the first several years of the 19th century, especially beginning with the 1801 deposition of Osei Kwame, leader of the province, one reason for which was “his inclination to establish the Korannic law for the civil code of the empire”. Many rebelled against his overthrow, and they were gradually defeated by the Ashanti government over three years. At one of the last battles in 1804, the Ashanti representative in the city Bonduku defeated the rebel forces in control of Bouna. In the midst of this battle, Bakr was imprisoned. Bakr walked as a prisoner carrying heavy packs on his back via the “old slave route” from Bouna, to Bonduku, to Kumasi, and finally to Lago, at the coast. He was sold around 1805 to an English ship. (Curtin, 154)

Education

He was highly educated in Bouna and studied mostly the Koran. Due to his youth he had not yet progressed to other subjects such as math and rhetoric (Curtin, 153).

In his later life, there were several remarks of surprise at the extremely high level of his education, especially for someone who was captured and enslaved unable to continue his education past the time he was 14.

Documentation

The primary information for Bakr comes from the autobiography he wrote, and from letters sent between him and another freedperson in Jamaica after the abolition of slavery. The two men were put in touch by English magistrates who were to help oversee the end of slavery. It seems they knew them both personally and encouraged them to write each other because they were both highly educated speakers and writers of Arabic.

If he hadn’t been so highly learned and highly literate. we may never have this information about him, for a double reason: the magistrate may have never noticed him to take a particular interest in him, which is what may have kept these writings protected; and secondly he would have never written it

Historical Significance

Ironically, if it weren’t for the fact that Bakr had been kidnapped and taken as a slave; then freed while in Jamaica; we would have had, ironically, much less documentation about many of the areas, locations, traditions, names of family members and tribal leaders, religious leaders, and formal institutions of the region he came from.

For example the educational institution he studied at in Buouna was otherwise known by only indirect evidence from surviving works of scholarship produced from that specific region during that time, suggesting a center of learning in this area, and from one obscure reference to the “center for learning” there, referenced by Barth (Curtin, 153)

it was “known only from Barth’s short reference to it, as ‘a place of great celebrity for its learning and schools, in the countries of the Mohammedan Mandingoes to the south’ ” (153)

Sources

The McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning

328 Frist Campus Center, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544

PH: 609-258-2575 | FX: 609-258-1433

mcgrawdll@princeton.edu

A unit of the Office of the Dean of the College

© Copyright 2026 The Trustees of Princeton University