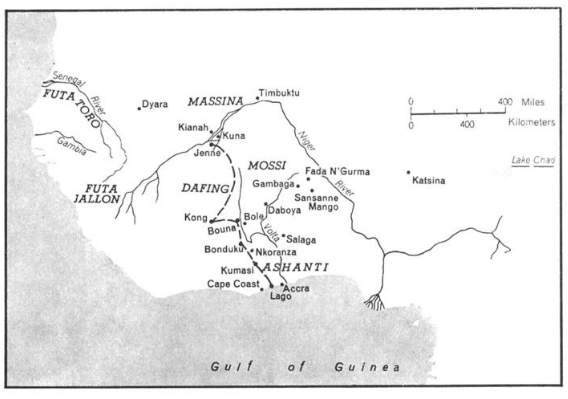

After reading Freedom Papers by Rebecca Scott and Jean Hebrard, I began researching biographies of other West Africans who were captured and brought to the Caribbean also around the turn of the (19th) century. One interesting figure came up that had many similarities. Abu Bakr al-Siddiq was, like Rosalie, captured from Western Africa as a young person, around the age of 14, and may have had a similar experience in several respects. You can see her region of Futa Turo farther west between the Senegal and Gambia Rivers, which you can compare to his birthplace and travels over land from Timbuku to Ashanti.

Map (Source)

Bakr was captured several years after Rosalie, however, and transported on an English slave ship in 1804, just 3 years prior to Parliament’s 1807 abolition of slave trade.

In contrast to Rosalie, Bakr’s movements are much more documented, since the record we have for him comes from a self written autobiography. For the historian, the record available is much less fragmented and more continuous. In addition his life story was less fragmented and more continuous, as he remained on the one island, Jamaica, until the time he was legally freed in Britain’s 1833 Emancipaion Act. He did, however, have many travels in Africa both before his capture and later after his legal emancipation.

Bakr’s autobiography was translated into English from his original writing in Arabic; first himself in 1834, and then professionally translated in 1835. (During his time as a slave in the “New World” he learned to speak English but he wrote only in his native Arabic, so his own verbal translation was recorded by a scribe).

You can access the full text in English of his own autobiography online here (begin at page 157). Prior to this text is a summary of his biography by modern historian Ivor Wilks (p. 152-157).

Childhood

Abu Bakr al-Siddiq was born in Timbuktu around 1790. (Curtin, 157) His father was named Kara Musa (157), and mother was named Hafsa (159). He spent his early life in Jenne (153,165), and much of his education in Buona (165).

Map (Source)

At age 9, after the death of his father, his tutor first considered arranging for him to a pilgrimage (hajj), and then instead brought him on a long journey to Buona, after learning of master educators there. Considering the number of miles from Timbuktu to Buona, and the speed of travel with animals or on foot, one can imagine this trip was broken up into small segments. This was typical of travel in this time period. For example, an essential Muslim sacrament is the pilgrimage to Mecca. That trip was one which was very typically broken up into many small trips over many years of one’s life.

In Bakr’s own incredible story of travel, in his case, for the sake of his education: “before reaching the age of nine, he had traveled with his tutor more than 600 miles. Then he spent a year in Kong, and went to Bouna for further education.” (Source) “In all these places, he had relatives and in-laws. One historian “remarked humorously that belonging to Islam was like belonging to a touring club” (Goody 1968:240, quoted here )

The Ashanti province ,where Buona was located, had faced civil and political upheaval in the first several years of the 19th century, especially beginning with the 1801 deposition of Osei Kwame, leader of the province, one reason for which was “his inclination to establish the Korannic law for the civil code of the empire”. Many rebelled against his overthrow, and they were gradually defeated by the Ashanti government over three years. At one of the last battles in 1804, the Ashanti representative in the city Bonduku defeated the rebel forces in control of Bouna. In the midst of this battle, Bakr was imprisoned. Bakr walked as a prisoner carrying heavy packs on his back via the “old slave route” from Bouna, to Bonduku, to Kumasi, and finally to Lago, at the coast. He was sold around 1805 to an English ship. (Curtin, 154)

Education

He was highly educated in Bouna and studied mostly the Koran. Due to his youth he had not yet progressed to other subjects such as math and rhetoric (Curtin, 153).

In his later life, there were several remarks of surprise at the extremely high level of his education, especially for someone who was captured and enslaved unable to continue his education past the time he was 14.

Documentation

The primary information for Bakr comes from the autobiography he wrote, and from letters sent between him and another freedperson in Jamaica after the abolition of slavery. The two men were put in touch by English magistrates who were to help oversee the end of slavery. It seems they knew them both personally and encouraged them to write each other because they were both highly educated speakers and writers of Arabic.

If he hadn’t been so highly learned and highly literate. we may never have this information about him, for a double reason: the magistrate may have never noticed him to take a particular interest in him, which is what may have kept these writings protected; and secondly he would have never written it

Historical Significance

Ironically, if it weren’t for the fact that Bakr had been kidnapped and taken as a slave; then freed while in Jamaica; we would have had, ironically, much less documentation about many of the areas, locations, traditions, names of family members and tribal leaders, religious leaders, and formal institutions of the region he came from.

For example the educational institution he studied at in Buouna was otherwise known by only indirect evidence from surviving works of scholarship produced from that specific region during that time, suggesting a center of learning in this area, and from one obscure reference to the “center for learning” there, referenced by Barth (Curtin, 153)

it was “known only from Barth’s short reference to it, as ‘a place of great celebrity for its learning and schools, in the countries of the Mohammedan Mandingoes to the south’ ” (153)

Sources

Leave a Reply