With nearly 12 million followers on Spotify, Hip Hop is a form of art widely recognized and enjoyed by individuals across the world. However, despite its large following, it is a genre of music often linked with the trends of violence amongst America’s youth. In an attempt to understand the role of Hip Hop in forming a Black Diasporic Consciousness, this project will tackle Hip Hop’s trajectory with a focus on its roots, the messages artists were and are able to convey through it, and, most importantly, the ways in which it has established a community amongst disenfranchised Black youth who have not always been welcomed within the larger society.

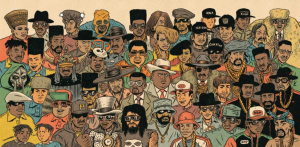

While Hip Hop encompasses DJ-ing, MC-ing, breakdance, graffiti, and knowledge –“the Afro-diasporic mix of spiritual and political consciousness designed to empower members of oppressed groups” (Gosa, 2014)— this project will focus primarily on the DJ-ing and MC-ing—aural and oral components—as well as the knowledge—the mental component—that inspires it.

Hip Hop’s Rise and Roots

The United States

Beginning with the rise of Hip Hop in the United States, a quick google search leads us to a back to school jam in the Bronx, NY:

“On August 11, 1973, an 18-year-old, Jamaican-American DJ who went by the name of Kool Herc threw a back-to-school jam at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx, New York. During his set, he decided to do something different. Instead of playing the songs in full, he played only their instrumental sections, or “breaks” – sections where he noticed the crowd went wild. During these “breaks” his friend Coke La Rock hyped up the crowd with a microphone. And with that, Hip Hop was born”

While this first instance occurred in New York, DJ Herc drew his inspirations for what would become Hip Hop from both American and Jamaican musical traditions. On the American side, influenced by soul, rock, and funk DJ Herc’s style spawned a global youth culture, rooted in the African American inner city experience. Using Jamaican influences, DJ Herc encouraged his crew of hype-men, the MCs, to recite rhymes over the microphone, in the style of reggae and Jamaican dancehall toasting, which pioneered the art of rapping.

After DJ Kool Herc introduced the Bronx to Hip Hop, it was embraced by DJs spinning at parties, and their MCs, as a way for a small community of people living in the South Bronx to show discontent with the hard times they were going through. It quickly evolved and spread through NY in a way that allowed individual artists to contribute to the genre with their own Diasporic backgrounds.

The Ghetto Brothers, a Puerto Rican gang, was known for plugging their speakers into the lampposts at 163rd Street and Prospect Ave to throw block parties that broke down racial barriers between Hispanics, Blacks, and Whites. English-speaking Blacks from Barbados like Grandmaster Flash were known for introducing the rhythms from salsa music, as well as Afro Congo and bongo drums. Much like DJ Herc, these youths mixed their influences with existing musical styles associated with African-Americans prior to the 1970s, such as jazz and funk. Others like them were influenced by sources such as The Last Poets, a spoken word group from Harlem who had been delivering political street-poetry since the early 1970s; scatting in jazz, a form of singing in which one’s voice is used as an imitation of instruments; and traditional black oration. In addition, African American public figures like Muhammad Ali, and his rhyming boasts, and Martin Luther King Jr.‘s powerful speeches were major influences as was the musical style of rhythm and blues performers such as Issac Hayes.

By the mid-1970s, American Hip Hop was dominated by turntablist and saw its first hit song in 1979 with Rapper’s Delight by the Sugarhill Gang. With this it migrated from New York to Los Angeles and Chicago, then to smaller cities such as Philadelphia and Atlanta. Though at first Hip Hop was primarily hierarchically diffused, meaning it would spread from one major urban center into less populated areas, the cultural phenomenon eventually spread down the ranks of the population hierarchy. From cities, Hip Hop worked its way into suburban towns, and by the 1990’s, it had eventually spread to small rural communities across the United States.

Hip Hop’s introduction to the general American media was met with much excitement as MCs transitioned from commentaries about the crowd attending their parties to raps about their personal experiences and stories. Largely, as it spread within the United States, Hip Hop culture became defined and embraced by young, urban, working-class African-Americans. Its aural components seemed to originate from a combination of traditionally African-American forms of music—including jazz, soul, gospel, and reggae. As such its creation was credited to working-class African-Americans who took advantage of the tools available to them—vinyl records and turntables—to establish a new form of music that both expressed and shaped the culture of Black youth in the 1970s.

African Traditions

While strong associations exists between Hip Hop and the inner city youth who popularized it, these origin stories ignore the longer history of oral traditions that have long informed Africans and African diasporic cultures. Thus, if we were to just focus on the American components of Hip Hop, we would lose many of the African traditions that inspired it. First and foremost, the oral component of Hip Hop can be tied to the West African oral tradition Nommo (Blanchard, n.d.). In Malian Dogon cosmology, Nommo is the first human, a creation of the supreme deity, Amma, whose creative power lies in the generative property of the spoken word. As a philosophical concept, Nommo is the animative ability of words and the delivery of words to act upon objects, giving life. Under this description, Nommo allows us to view Hip Hop as a form of art that is not just meant to go in one ear and out the other. Instead, the words artists use give life to their ideas, their feelings, and their experiences. The words are illuminating the experiences and the people that are too often erased.

Nommo implies the power of words to create harmony and balance in the face of disharmony

Further, while Nommo focuses on the spoken word and thus the oral component of Hip Hop, artists themselves can be linked to griots, the respected African oral historians and praise-singers (Fargion, n.d.). Griots were the keepers and purveyors of knowledge, including tribal history, family lineage, and news of births, deaths, and wars. Travelling griots spread knowledge in an accessible form—the spoken word—to members of tribal villages who did not otherwise have access to such information.

Much like griots in Africa, in the United States Hip Hop artists create songs that, through performances, albums, and the internet, spread news of their daily lives, dreams, and discontents outside of their neighborhoods. Hip Hop artists are viewed as the voice of poor, urban African-American youth, whose lives are generally dismissed or misrepresented by the mainstream media. They are the keepers of contemporary African-American working-class history, concerns, and experiences.

The Role of Slavery

The power of Hip Hop music is most closely identified with that of slave narratives. The reason behind slavery music, poetry, and narrative was to help slaves in freely expressing their opinion in ways that were unique and exclusive to their society. It paved the way for African slaves to identify with each other, and create a history that was not based on the American culture. Through African slaves, the African-American community was created, along with a new language which eventually contributed to the development of a new community, the Black American people in the American continents. Looking at a different perspective, slavery led to Africans living in different continents worldwide while slavery songs made it possible for the slaves to work through their struggles while creating a community, which identifies significantly with the existence of Hip Hop.

As it stands, Hip Hop’s role as a form of art that spreads political opinion can also be tied to African-American rhyming games—a form of resistance to systems of subjugation and slavery. As per Blanchard, rhyming games, like the modern Double Dutch rhymes, encoded race relations between African-American slaves and their White masters in a way that allowed them to pass the scrutiny of suspicious overseers. Additionally, these games allowed slaves to use their creativity to provide inspiration and entertainment for their peers. As per Hip Hop journalist Davey D, this African oral tradition is highly linked to modern Hip Hop:

“You see, the slaves were smart and they talked in metaphors. They would be killed if the slave masters heard them speaking in unfamiliar tongues. So they did what modern-day rappers do—they flexed their lyrical skillz” (D, 1998).

Hip Hop can thus be understood as a form of resistance to the modern suppression of working-class African-Americans which must be largely credited to the slavery movements and African traditions that came before it. In other words, the origins of Hip Hop are both longer and more geographically disperse than popular notions would have one believe.

Politics of Hip Hop

Hip Hop, just like the music created during the time of slavery, represents the struggle of the African–American community. The earliest rap recordings in the 1980s were largely positive in tone even as they explored and exposed the gritty conditions of life in the nation’s urban ghettoes. By the 1990s this generation would be eclipsed by gangsta rap. West coast artists such as Ice-T and NWA related rugged and explicit stories of slum-life which often exaggerated gang violence and bravado. Much to the consternation of the American public outside the Hip Hop community, gangsta rap became and remains one of the most popular sub-genres of rap music. The implicit image of rap and violence became explicit with a number of incidents including most notably the murders of Tupac (2Pac) Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G., two of raps biggest stars. Many observers debated whether gangsta rap caused or simply reflected the rising gang violence of the decade.

Showcasing the more uplifting side of Hip Hop, one of the most famous Hip Hop artists, Rick Ross, sang a song, “Hustling”, which focuses on the act of obtaining money often in crafty ways. For slaves, one of the many reason why it was difficult to gain freedom was because they lacked resources and were identified as a sub-class group. In the United States, many decades after the end of the slave trade, African-American people still represent the highest number of unemployed people in the country. Songs like “Hustling” represent the reality of the African-American community in the world today, who after decades of struggle to gain independence and earn full rights as citizens, are still treated like minorities with less rights.

Following the focus on Blacks ability to succeed and hustle, Tyga, a Hip Hop artist, once sang that he “made college money, without college” he was a “post traumatic slave”. These lyrics were in collaboration with the famous theorist Dr. Joy DeGruy Leary who diagnosed the Hip Hop community with post-traumatic stress disorder which in turn made them Post traumatic slaves.

Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome is a condition that exists as a consequence of multigenerational oppression of Africans and their descendants resulting from centuries of chattel slavery. A form of slavery which was predicated on the belief that African Americans were inherently/genetically inferior to Whites. This was followed by institutionalized racism which continues to perpetuate injury.

Continuing with the realities of life, Hip Hop artist Meek Mill uses his music to paint a picture of his experiences growing up in a crime and violence-filled environment in Philadelphia.

In the last verse of this song, “Traumatized,” Mills states,

“When I find the n— that killed my daddy know I’mma ride

Hope you hear me, I’mma kill you n—

To let you know that I don’t feel you n—

Yeah, you ripped my family apart and made my momma cry

So when I see you n— it’s gon’ be a homicide

Cuz I was only a toddler, you left me traumatized”

Mill lays out how the loss of his father ruined his childhood and fuels his anger. He was so angry that he threatened to murder the man who killed his father. In the verse, Mill is communicating his experience of depression and anxiety that stemed from poverty and violence. As Mill mentions, he lived in a world of constant fear of police and other youth coming after him. Mill’s experience of anger is likely an expression of underlying emotions such as sadness and fear from years of trauma. This experience is common among many Black youth, particularly those in low-income communities.

Thus, Mill’s music can tell us a great deal about how violence is perpetuated in the Black community. He describes the endless cycle of violence that began (for him) with the loss of a parent. Losing his father changed his worldview; he views the world as an unsafe place where he had to commit crimes and violent acts to have his needs met. Moreover, Mill’s music highlights that rap is one of few settings where it is acceptable for Black youth to express their feelings. Mill can freely express his feelings of pain, fear, sadness and anger in a way that is socially acceptable because it is laid out over a nice beat.

Given the ways in which the African-American experience has been shaped by the legacies of slavery, segregation, and economic and political subjugation, many artists understand the existence of Hip Hop as a way to convey their experiences and the oftentimes tragic history that shaped it. Specifically with Mill’s perspective in mind, given the criticism of Hip Hop as being too violent and sexual, and its shaky trajectory with politicians as seen in this timeline, many artists defend the presence of violence in their lyrics by viewing it as a manifestation of African-American history and culture. Journalist Michael Saunders writes:

“The violence and misogyny and lustful materialism that characterize some rap songs are as deeply American as the hokey music that rappers appropriate. The fact is, this country was in love with outlaws and crime and violence long before Hip Hop” (Tucker, 1996).

Similarly, Los Angeles Congresswoman Maxine Waters came to rap’s defense in 1994 when she stated:

“It would be a foolhardy mistake to single out poets as the cause of America’s problems…These are our children and they’ve invented a new art form to describe their pains, fears and frustrations with us as adults.”

Hip Hop’s Role in Fostering Black Empowerment

Although one of the original corollaries of Hip Hop culture was the illumination of racial and socioeconomic injustices, which are deeply embedded within American culture (Peoples, 2008), critics of the genre highlight that this outcome has been overshadowed and undermined by the misogynistic and violent themes expressed in contemporary Hip Hop music. In fact, several Afrocentric critics (Ayanna, 2007; Engles 2007; Stewart, 2004), have called attention to the sex, violence, materialism, and misogyny communicated in the mainstream Hip Hop music and video genre and culture. In addition to the negative impact that modern-day Hip Hop music has had on the perception of Black culture, it has also been criticized for perpetuating the internalized oppression of Black women. In essence, the overt and pervasive disrespect and denigration of Black women within contemporary Hip Hop culture has been suggested as being devastating to the psyche and identity development of Black women (Henry, 2008).

However, for today’s society, Hip Hop is not just music; it is comprised of fashion, arts, icons, and it is a unique culture. Originally, Hip Hop was created with the propensity to gauge the psychology and lived experiences of young people growing up in underrepresented neighborhoods. Further, it was used as a voice for disenfranchised youth of low-economic areas, and it served as a battleground for respect and recognition in the world. Many of the same claims can be made about Hip Hop’s current standing.

In the words of Oddisee:

“[Hip Hop] is a music that is very much about current affairs. Whatever is happening right now within a day or two will find itself in a hip hop song and with the use of the internet it spreads to hundreds of thousands of people instantly.”

Beyond questions of cultural consumption and reproduction, it can be argued that Hip Hop’s expanding global reach has facilitated the contemporary making and moving of Black diasporic subjects themselves. African descendant youth in an array of locales use the performative contours of Hip Hop to mobilize notions of Black-self in ways that contest and transcend nationally bound racial framings. Hip Hop in this way can be seen as enabling a current global (re)mapping of Black political imaginaries via social dynamics of diaspora. While individuals of African descent may be separated by oceans and borders, Hip Hop allows these individuals to communicate the trials and tribulations faced by their communities while also celebrating the beauty that comes from the Black Diaspora.