History tends to forget the masses. In remembering past events, stories, and antecedents, we seek out the faces of inspiring leaders and monumental figures we can put on mountains and quickly associate with particular eras, ideologies, and groups. In doing so, however, we silence the stories and contributions of the ordinary person. For instance, the narrative of the black American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s proudly proclaims the stories of Ella Baker, Rosa Parks, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X, while not completely acknowledging and exalting the efforts of the thousands who marched, boycotted, and otherwise supported and drove the civil rights effort to fruition.

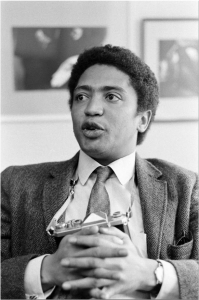

Similarly, Joseph Louw, a South African photographer and a contemporary of these great historical figures, fell into the desire to capture these narratives. Upon graduating from Columbia University, he found work for the Public Broadcasting Laboratory (PBL), a television series created by the National Educational Television (NET). As a young photographer, he had the unique privilege of being asked to follow Dr. King to document images for a documentary PBL was creating about Dr. King. In addition to this once in a lifetime opportunity to interact with one of the great and influential leaders of all time, he was stationed with Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) as they organized the Poor People’s Campaign. Louw was given a platform to interact and communicate with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. about his past approach to gaining civil rights for black Americans as well as witness firsthand the initiation of the economic “chapter” of the fight for equality. While history books and many today see Dr. King’s message as a message of nonviolence and black equality, this part of his message is an interestingly relatively unknown final caveat, even preaching that this campaign was “the beginning of a new co-operation, understanding, and a determination by poor people of all colors and backgrounds to assert and win their right to a decent life and respect for their culture and dignity.”

Joseph Louw was there in the midst of it all. On April 4, 1968, the night of the assassination, he was in his motel room a few doors down from Dr. King’s. Having finished eating dinner early, he chose to watch a television broadcast, which was showing footage from Martin Luther King Jr’s “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech from the day before, most notable for its call for pan-Africanism and his declaration that he was ready to die. See: https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkivebeentothemountaintop.htm Little did Louw know that that would be his final speech, a fitting end to the brave life of a great leader.

Just as the news broadcast ended, Louw heard a loud noise. He ran outside to the balcony to find chaos. Dr. King’s body was on the floor, four men kneeled and stood beside him, pointing at the direction of the assailant. Deeply impacted by the horrific scene in front of him, Louw later recounted that he could only think of the horror of the incident and the necessity of recording the incident with a photograph for the whole world to see. At that moment, he took the iconic photo and took several other photographs following the attack, including photos of armed policemen rushing to the scene, ambulance workers attending to the mortally wounded Dr. King, and grief-stricken civil rights workers in the aftermath of the assassination. See: https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/constituents/joseph-louw?all/all/all/all/0

Following the assassination, Louw went back to New York where PBL was based to develop his rolls of film. His photos soon became some of the most widely recognized and most powerful images captured of the civil rights movement. The media response was nearly immediate, with PBL airing the incomplete and unfinished documentary with Louw’s eyewitness testimony. See: https://www.thirteen.org/blog-post/mlk-assassination-the-story-behind-the-photo/

Louw’s contributions to history include the photographs he took, the media response to Dr. King’s assassination, as well as valuable insights on what it was like to be with Dr. King in his final days. To conclude, Louw nobly decided that any revenue from the photographs he took from the night of the assassination would be contributed to organizations whose missions aligned with the message and work of the late Dr. King.