How fare the Æsir? How do the elves fare?

Jotunheim seethes, the Æsir assemble;

at the stone doorways of deep-stone dwellings

dwarves are moaning. Seek you wisdom still?— The Völuspá (trans. Terry)

The Völuspá’s most obvious religious content is flashy. The cast of Norse gods, as wrought contemporaneously in expensive metal. But the poem also encodes a type of belief based more in ritual than in text or metalwork, one that hasn’t been preserved as well as its higher-status counterpart. The Völuspá suggests, but does not explicate, a cosmology of strange beings: dwarves, elves, giants, others. These names are recognizable to us today largely from their appropriation by British author J.R.R. Tolkien in his Middle Earth writings, and their subsequent influence on the genre of fantasy in literature, film, and video games. This influence is pervasive; a glance over the Völuspá will reveal that many names from Tolkien’s The Hobbit, for instance (including Thorin, Fili, Kili, Thror, Thrain, and of course Gandalf) were lifted verbatim from the Old Norse text.

Tolkien is an interesting author with whom to consider the Völuspá for another reason: his writings are an example of explicit Christian synthesis of Old Norse culture, an appropriation with a long history in Iceland. The Völuspá was put to paper by Christian scribes, later interpreted in prose by the Christian poet Snorri Sturluson (Dunn xvi). The Völuspá‘s content remains debated among scholars: to what degree can it be considered a truly pagan text? A Christian one? In this section we will use Tolkien as a jumping off point to consider the Völuspá in the context both Christianity and the small, strange creatures of the earth, linking two types of ‘other belief.’

A different cosmology: beings of the land

Reading through the Völuspá, one is confronted with a flood of beings. At different points in the poem, a reader will encounter “giants,” “Norns,” “valkyries,” “dwarves,” “elves,” and any number of special animals, including a “Serpent,” a “Wolf,” and in the poem’s very last moments, even a “dragon.” We might have associations from pop-culture for many of these beings—a valkyrie might invoke the image of the aforementioned Tessa Thomson, for example. But others remain unknown, elusive.

Neil Price writes about the other beings present in Old Norse belief in his book, Children of Ash and Elm. First, he laments the impossibility to picture the Norse mythos today: “it would be disingenuous to claim that such beings can ever be truly viewed now without thinking of their later incarnations in Tolkien and other fantasy properties” (56). But he also emphasizes the importance, even omnipresence of these beings in the Viking Age: “Anyone moving through the landscapes… would have understood themselves to be in the midst of teeming life… [these beings,] that other population with whom humans shared their world…. played a far greater part in people’s everyday lives than… the gods” (55-56). In other words, an attempt to reach across the divide is warranted.

We get a glimpse of the importance of the unseen beings of the world in The Saga of Thorstein Bull’s-Leg:

The first provision in the pagan law code was that people should not sail ships with dragon’s heads at sea. But if people did, they were obliged to take the heads down before they came in sight of the land and not sail ashore with gaping heads of yawning snouts which would frighten the nature spirits of the land .

— The Saga of Thorstein Bull’s Leg (trans. Clark)

The “first” (and presumably most important) law inaugurated by the Althing warns against “frighten[ing]” nature spirits. As Neil Price put it eloquently, “Such legal strictures tend not to be frivolous, so this should be taken seriously” (55). What other manifestations do these beings take, and where can we find evidence of them in the Völuspá? We see dwarves, the miners of Tolkien fame, in the midst of the poem’s Ragnarök section:

at the stone doorways of deep stone dwellings

dwarfs are moaning.— The Völuspá (trans. Terry)

Though they are “deep” within their abodes in the stone, the dwarves are affected enough by the fighting to “moan.” They are clearly connected to the world, feel the pain it feels. This points to two important elements of the unseen beings within the cosmology of the Norse religion: the strange beings may be hidden, but they are still important, omnipresent.

Price laments the “medieval” misconception that the dwarves were small, explaining that they were roughly the same size as humans and were “skilled craftworkers, jewelers and miners.” This is perhaps not so different from the widely proliferated fantasy version of dwarves. He also points out that dwarves were not particularly active in the human world: “They kept to themselves” (57). How should we, as moderns, depict the dwarves, despite their paradoxical invisibility? One strategy is to take an object linked very closely with the unseen beings of the earth, something that is not often depicted in exhibits: pieces of the Icelandic landscape that contemporaries of the Völuspá may even have interacted with.

Stone Sculpture from Síðumúli, Iceland.

Possible Madonna, 1400s?

Basalt, H. 1.86 m

(source: Wikimedia)

Here is a stone. It is old, very old, as most stones are. It seems to be special stone. It is carved (for a funerary purpose, perhaps?) but the carvings on it do not appear to be figural, or textual. They are merely shapes, which isn’t to say that they are merely anything; they simply don’t seem to have a distinct, abstractable meaning that’s been passed down to us. Perhaps something like this, with its own missing information, can stand as an oblique proxy, making tangible the parts of Norse belief we can’t comfortably comprehend.

Christianity and Syncretism

Is the Völuspá Christian? Does it bear Christian traces? Such questions bear asking. None of the scholars dismiss them out of hand, but some give a direct answer. Pálsson wrote that the text was “essentially pagan in spirit” despite Christian borrowings (8) while Dunn says the Völuspá and the other lays are “basically a product of the pre-Christian Norse culture of Norway” (xvi). This isn’t an attitude directly contradicted by the text, but not necessarily confirmed by it, either. Some of the complication comes from the fact that the poem exists in two different manuscript versions. One, the Hauksbok version, contain several lines not in the Codex Regius version of the text:

The mighty one comes down on the day of doom,

the powerful lord who rules over all.— The Völuspá (trans. Terry)

Patricia Terry does not include these lines in the main body of her translated text. In her notes, she argues that the lines have “Christian connotations,” that it make difficult for them to reconciled with the rest of the poem. She says the lines are “hard to fit into the chronology and what seems to be the spirit of the poem” (10). Vésteinn Ólason goes further than Terry, saying “it seems obvious that this being is modelled upon the image of the Christian God” (36), and, later, that the argument of the lines “is totally out of touch with the other parts of the poem.” He says that “In [his] opinion” the lines were a late and hasty addition, an “attempt to mediate between the pagan world view of the poem and the Christian world view.” (37).

Arguments intending to find an original, pagan poem within the Völuspá are important for our understand of the text’s history, but they remain controversial. Gísli Sigurðson wrote a different chapter in the same book as Ólason. According to him, such an original or pagan Völuspá does not exist. The Völuspá was derived from an oral narrative, therefore:

[O]ur present Völuspá(s) [i.e., according to the different manuscripts] is/are a reflection of how Christian Icelanders in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries interpreted what they knew about the pagan religion and pagan world view from their foremothers and -fathers…. this model means that what we call the Völuspá can not be seen as being either Icelandic or Norwegian, Sami or English, pagan or Christian.

— Sigurðson, “Völuspá as a Product of an Oral Tradition”

Purity in the Völuspá is, in Sigurðson’s opinion, a lost cause. We must take the texts we have at their own level, without searching for something that fits neatly with a pre-determined shape or perspective for the text. We can bring a similar method to material culture, especially in contexts where pagan and Christian registers—as we identify them—seem blurred.

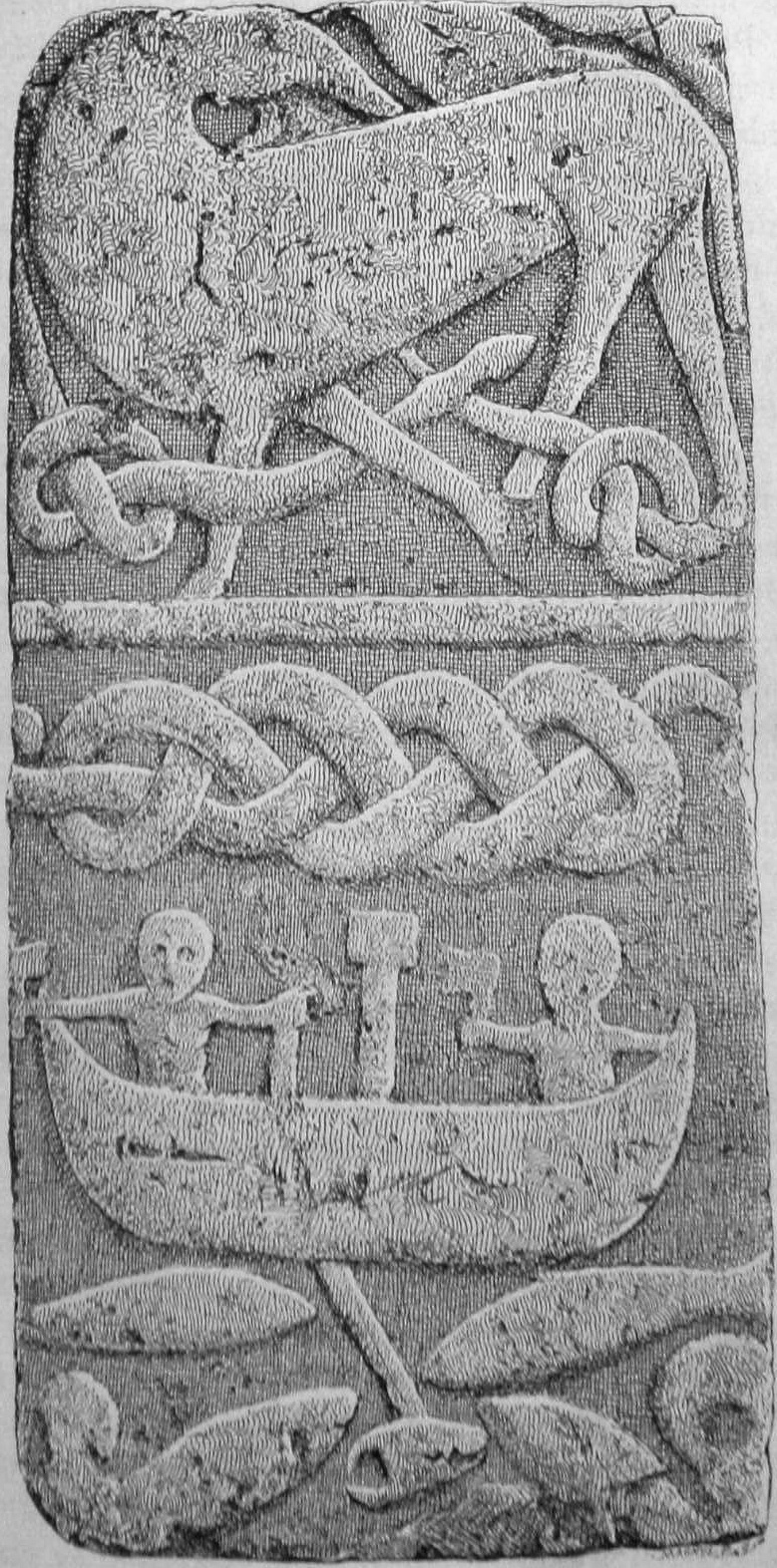

Engraved stone from Gosforth, EN.

Sandstone, H. 70 cm.

(source: Wikimedia)

Above is an engraving of a “fragmentary slab… in the church at Gosforth, Cumbria” (Graham-Campbell 156). Like the image of Thor at Altuna, in Section II, it depicts a figure with a hammer fishing—Thor fishing for the world serpent during Ragnarök. Where this image differs is in its context. It was found in the same graveyard as another artifact, the Gosforth cross. According to Graham-Campbell, the Gosforth cross mixes scenes from Ragnarök with images from Christian theology (173). Given the shared location, might this picture stone have been created in a similar milieu to the cross, where pagan and Christian bounds are being breached? The Altuna picture stone and this slab depict almost identical scenes. But the Gosforth fragment exists in a context where a new symbolism is emerging or has emerged.

Despite a divergent setting, the two images are not entirely discrete. The worldview of one object’s context (apparently entirely pagan) bleeds, by association, into another’s (tenuously Christian). Where is the line between them? Is there a satisfactory differentiation? Perhaps our fixation with the divide between pagan and Christian sources is a modern construction. Perhaps the apparent incoherence in symbolism we see in material such as these—or texts like the Völuspá—is rather a fluidity that remains difficult for us, in our rigidity, to confront.

« Previous | Home | Next »