The Oseberg ship is one of the most famous Viking relics today as it is the largest and best-preserved ship that we have from the Viking Age, dating back to some time in the ninth century CE. Along with the ship, archaeologists have found two women inside the ship buried alongside, among other things, silk fabric mostly from Central Asia and Constantinople with a few pieces from China. These fabrics come in a variety of colors and contain different motifs, oftentimes reflecting the cultural symbology of their place of origin.

Silk fragment with bird figure from Oseberg, NO.

(source: UNIMUS)

Of the items discussed by Vedeler in her article on these silks, I want to hone in specifically on number 11, as I find it to be the most interesting.1 As Vedeler notes, the top of the silk fragment very visibly contains a bird holding a tiara in its beak. She infers this to be a Zoroastrian motif and perhaps syncretized with patterns from Chinese silk as the bird on the fragment is a duck, typically depicted in Tang Dynasty silk. This silk fragment is quite small and uniform in its rectangular shape, as are almost all the silk fragments from the Oseberg ship, suggesting that these silks were not used wholesale but cut into pieces and then used.

I want to use Vedeler as a secondary source for this silk fragment although I got the fragment from her paper as I find it quite interesting. Toward the end of her article, she makes a case for the importance of silk beyond just its aesthetic or economic value. Specifically, she argues that silk was political as well. Silk was exchanged not just between Central Asian producers and their European customers but fostered political connections between Scandinavia and Catholic Europe. Even within Scandinavia, she argues, the foreignness of silk possessed a “sacral power,” through which it granted power and legitimacy to the wearer.

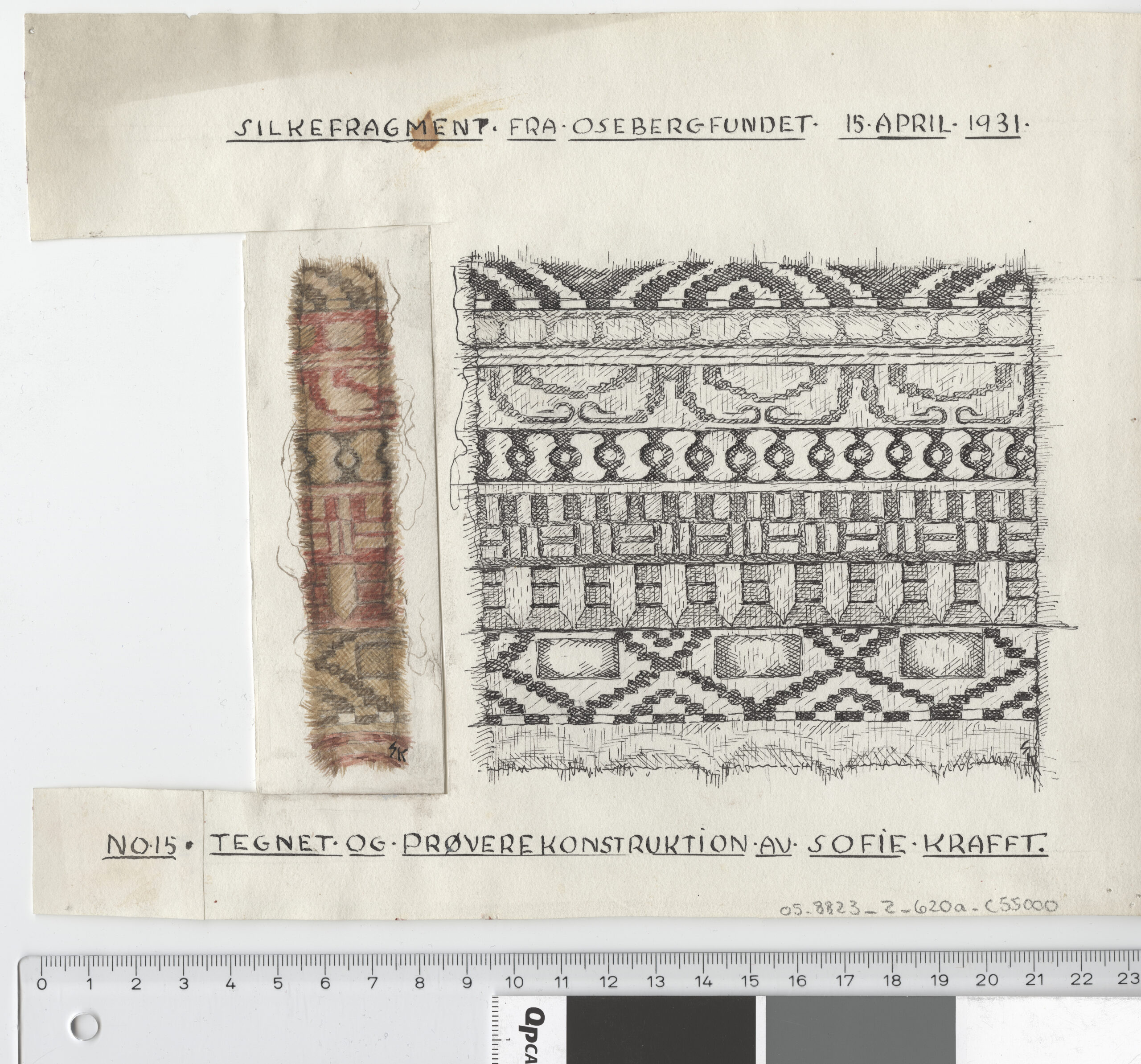

Silk fragment and reconstructed pattern from Oseberg, NO.

(source: UNIMUS)

Vedeler’s own article was a discussion of the silk fragments I’ve chosen so I do not want to rehash her arguments. Instead, I want to imagine the role of silk in Viking Scandinavia more broadly than how she described it. Silk seems to have become a tool in Scandinavia just like how Islamic coins were. As Vedeler mentions, silk had power in Scandinavia seemingly without regard for the quality of the silk itself. Furthermore, it changed in function too. Rather than serving as a fabric to be worn wholesale, pieces of silk almost become embroidery in their own right, similar to how gold thread or pearls are woven into clothes both to enhance their aesthetic image as well as increase their value. In such a way, the Vikings took a material import like silk and made it their own by crafting their own meaning and usage for silk. Although it may be an odd comparison, I am reminded somewhat of the split identity of American Chinese food. While we in America usually just think of it as “Chinese” food, many of the ingredients, techniques, and even entire dishes are foreign to China and instead formed as an adaptation to cater to the American consumer or what is available in the United States. In such a way, the identity of the food changes into something that is just as American as it is foreign. When we discuss the Viking Age, we neglect to mention the transformation of culture once it enters the Viking World. As mentioned prior, entering the Viking World is a transformative process through which not only the role and significance of the material change but also their identity.

1 Marianne Vedeler, “Silk from Central Asia in a Viking Grave,” Arts of Asia 49, no. 3 (2019): 62-68.

« Previous | Home | Next »