There exist few parallels, particularly from Middle Eastern sources, to Ibn Faḍlān’s travel account about a group of Rūs, a medieval Arabic ethnic term very frequently used for Vikings, living along the Volga River in modern-day Russia.1 Visiting the Rūs was not Ibn Faḍlān’s original intention as he was instead sent as an ambassador by the Abbasid caliph to the Volga Bulgars, who had recently converted to Islam. However, Ibn Faḍlān wrote extensively about his experience with the Volga Bulghars, as well as the Rūs he encountered on his trip, in the tenth century CE as part of his Risāla, a popular genre of travel literature in the medieval Middle East through which he presumably sought to document his ambassadorial experience.

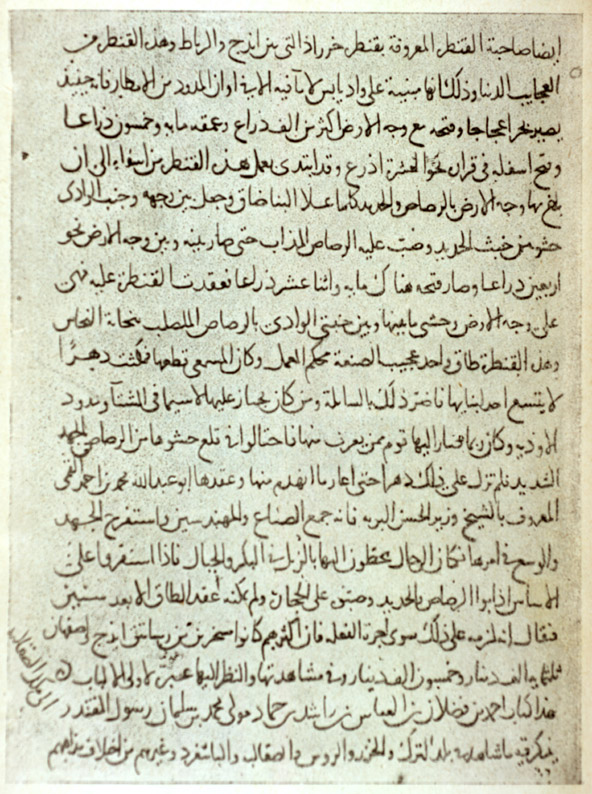

Ibn Fadlan’s Risala.

Ridawiya MS 5229 fol. 196v.

(source: Wikimedia)

As are many when discussing Ibn Faḍlān, I was concerned as to whether his accounts can be interpreted as referring to Vikings. Rūs, in medieval Arabic, was often used very broadly and Ibn Faḍlān’s Risāla discussion of the Volga encompasses a multiplicity of ethnic groups. Thorir Jonsson Hraundal, in his article about Arabic sources about the Rūs, argues that Arabic literary sources about Rūs living along the Volga should be interpreted as being Vikings and, in the process, he helps elucidate the significance of works like Ibn Faḍlān’s in studying the Viking Age.2 Setting aside traditional accounts of Rūs history such as The Primary Chronicle due to their obvious influence from biblical and Byzantine sources, Hraundal argues that medieval Arabic accounts have long been neglected as valid sources of information about Vikings in Eastern Europe and, more importantly for this study, argues that Ibn Faḍlān’s description of a Rūs funeral exhibits strong similarities to Old Norse sagas from the thirteenth century CE describing funerary practices of the cult of Odin. For me, not only does looking at Hraundal help validate the use of Ibn Faḍlān as an authentic source regarding the Vikings, but he also implicitly provides certain guidelines as to how to look at and analyze medieval Arabic sources about the Rūs such as Ibn Faḍlān’s.

Regarding Ibn Faḍlān’s risāla itself, his depiction of the Rūs is very negative. Although he praises the appearance, calling them “perfect,” he takes strong issue and disgust with almost every aspect of their culture, describing them as filthy and with no shame or modesty when it came to intercourse. However, it is important to keep in mind that Ibn Faḍlān’s perception of the Vikings is strongly shaped by his Islamic background. When he calls their mode of morning purification filthy, it is presumably done so in comparison to the Muslim ritual purification before prayer. He takes issue with Rūs men not bathing after intercourse because it is a religious commandment to do so. Although Ibn Faḍlān’s account does not contain an aspect of outside culture that’s indigenized by the Vikings, it reminds us that this path to indigenization is not a one-road street. When we read Ibn Faḍlān, we must constantly be aware that we are reading an account of the Vikings through a Muslim lens. All their features, positive or negative, are constantly being positioned against Islam. It is an etic account of the Vikings, through and through.

Silver Artifacts from the Exhibition “Vikings in the East.”

Moesgaard Museum, DK (2022).

(source: F Androshchuk)

This is not necessarily always a negative thing. Take, for example, how Ibn Faḍlān describes part of a ritual following the death of a chieftain. His female slave, who is to be killed to accompany her former master into the afterlife, is raised in the air multiple times and is quoted as saying, “‘Look, I see my master, seated in the Garden. The Garden is beautiful and dark green. He is with his men and his retainers. He summons me. Go to him.’” While we are unsure if the Rūs believed in Valhalla or not, we cannot tell from this text alone. That’s because the garden that Ibn Faḍlān speaks of is likely an obvious comparison being made to the Islamic afterlife, which is described as being a garden. The afterlife of the Rūs is likely translated as “Garden” to facilitate a better understanding for Ibn Faḍlān or his audience — whether the semantic shift to “Garden” from whatever the enslaved woman actually said happened with Ibn Faḍlān’s translator or Ibn Faḍlān himself as he recorded the event in his Risāla is unknown. In any case, despite Hraundal’s claim that Ibn Faḍlān’s account of Rūs funerary practices exhibits similarities to those we see in certain Old Norse sagas, we must be aware of the element of indigenization that exists in Ibn Faḍlān as well. Far from ignoring it, however, we should see it both as a way to see how Arab Muslims like Ibn Faḍlān put groups like the Rūs into perspective as well as how a normative, literary history of the Vikings is crafted.

1 Aḥmad Ibn Faḍlān, “Mission to the Volga,” ed. James E. Montgomery, in Two Arabic Travel Books: Accounts of India and China, edited by Philip F. Kennedy and Shawkat M. Toorawa, 163–297, Library of Arabic Literature, (New York: New York University Press, 2014).

2 Thorir Jonsson Hraundal, “New Perspectives on Eastern Vikings/Rus in Arabic Sources,” Viking and Medieval Scandinavia 10 (2014): 65–98.

« Previous | Home | Next »