Animal connection and sacrifice was common in the Viking Age to accompany human burials and other rituals.

| “The potential presence of a cowhide in which the interred individual was wrapped {…} supports a more commonplace social context rather than high status.”

Dove and Wickler, 35 |

A Viking Age boat grave at Øksnes in northern Norway was found with the body wrapped in a cowhide. Other grave items indicate that this was not a high status grave site but a more middling grave, suggesting that animal hide wrapping on the dead may have been a common cultural practice. |

| “These animals may have served as food offerings or displays of wealth. It is also possible that the mixing of humans and animals through cremation was linked to shamanistic beliefs in which human and animal identities were perceived as fluid, with the animal seen as a guardian, helping the person move into the next world.”

Poole, 146 |

Viking Age burials included many different sacrificed animals including horse, cattle, sheep, goat, pig, and dog. The decision of which animal to sacrifice for a human burial may have been correlated with the animal interactions that person had during life. The mixing of buried humans and animals reiterates the idea of fluid bodies and identities, with movement between the animal and human worlds as animals acted as one’s guardian, according to some mythologies during the Viking Age. |

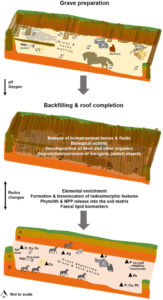

| Archaeologists are able to detect animals in Viking Age human graves even when few physical remains are visible to the eye. One new method involves fecal matter analysis of the grave soil. A burial at Fregerslev near Hørning in Denmark, for example, had traces of horse fecal matter, suggesting a horse was killed in the grave right before burial. Male horses are the most commonly excavated buried animal found in Viking Age Scandinavian graves. |

| “They then divide up his property or money {…} then lay it down, the biggest portion approximately in one mile from the homestead, then the second, then the third {…} And the smallest portion has to be nearest the homestead that the dead man is lying in. Then all the men who have the fastest horses have to be assembled {…} Then the man who has the fastest horse comes to the first and biggest portion; and so each after the other, until it is all taken.”

Ohthere and Wulfstan, 49 |

Horses were also used in other funerary rituals outside of sacrifice. Ohthere and Wulfstan is a text about two Norwegian travelers, incorporated into a longer Old English work. These travelers described journeys in Northern Europe, written around 890 CE. Their stories are important records of local customs and geographies at the time. The passage quoted here describes the use of horses in a race to divide up a dead man’s assets between his family and friends. |

| “Thor stayed the night there, and in the small hours before dawn he got up and dressed, took the hammer Miollnir and raised it and blessed the goatskins. The the goats got up and and one of them was lame in the hind leg. Thor noticed this and declared that the peasant or one of his people must not have treated the goat’s bones with proper care.”

Gylfaginning, 44

|

Gylfaginning describes Thor sacrificing his goats to feed himself and a peasant family during a long journey, then resurrecting them after the meal from just the goat skins and bones using his hammer. This both reiterates the connection between animals and mythology as most of the gods had an animal linked to them, like Thor and his two goats, and also represents the power of animal sacrifice to service humans and the gods. Thor’s anger over the peasants breaking the goat’s leg bone demonstrates the personal connection and importance of these animals to Thor. |

Bately, Janet. “Text and Translation: The Three Parts of the Known World and the Geography of Europe North of the Danube According to Orosius’ Historiae and Its Old English Version.” In Ohthere’s Voyages: A Late 9th-Century Account of Voyages along the Coasts of Norway and Denmark and Its Cultural Context, edited by Janet Bately and Anton Englert, 40–58. Roskilde: Viking Ship Museum, 2007.

Dove, Carla J., and Stephen Wickler. “Identification of Bird Species Used to Make a Viking Age Feather Pillow.” Arctic 69, no. 1 (2016): 29–36. (online)

Poole, Kristopher. “More than Just Meat: Animals in Viking-Age Towns.” In Everyday Life in Viking-Age Towns: Social Approaches to Towns in England and Ireland, edited by D. M. Hadley and Letty ten Harkel, 144–56. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2013. (online)

Sturluson, Snorri. “Gylfaginning.” [The Tricking of Gylfi] In Edda, translated by Anthony Faulkes, 7–54. London: J. M. Dent, 1995.

Sulas, Federica, Merethe Schifter Bagge, Renée Enevold, Loïc Harrault, Søren Munch Kristiansen, Thomas Ljungberg, Karen B. Milek, Peter Hambro Mikkelsen, Peter Mose Jensen, Vana Orfanou, Welmoed A. Out, Marta Portillo, and Søren Michael Sindbæk. “Revealing the Invisible Dead: Integrated Bio-Geoarchaeological Profiling Exposes Human and Animal Remains in a Seemingly ‘Empty’ Viking-Age Burial.” Journal of Archaeological Science 141 (2022): 105589. (online)

« Previous | Home | Next »