Transparent Subjects: Alterations in Iris van Herpen

Finding Subjects through the Transparent

By Lena Hoplamazian

“What first reads like the effort to accept things in their physical quiddity becomes the effort to penetrate them, to see through them, and to find… within an object… the subject.” – Bill Brown, A Sense of Things

Iris van Herpen’s 2012/2013 couture dress is a lesson in deflection. The plastic is so defensive and so otherworldly, the dress is immediately read as an exoskeleton. The shuttered strips of plastic reflect light, and paint shifting, ever-present white accent marks on the piece. The material cannot be easily understood; we cannot quite know what it is, where it came from, how it was made, due to the secrecy of the material itself. Iris van Herpen has a proprietary PVC that is never shared. What would usually be merely opaque black plastic is actually an almost-mirror. The material is constantly casting back to the looker, obscuring the wearer, casting and deflecting both light and the gaze. The dress looks as if to defend its internal object, despite making the wearer irrelevant and unnecessary. The dress is a beautiful, terrifying suit of armor, but protecting what? Armor for whom?

Iris van Herpen’s 2012/2013 couture dress is a lesson in deflection. The plastic is so defensive and so otherworldly, the dress is immediately read as an exoskeleton. The shuttered strips of plastic reflect light, and paint shifting, ever-present white accent marks on the piece. The material cannot be easily understood; we cannot quite know what it is, where it came from, how it was made, due to the secrecy of the material itself. Iris van Herpen has a proprietary PVC that is never shared. What would usually be merely opaque black plastic is actually an almost-mirror. The material is constantly casting back to the looker, obscuring the wearer, casting and deflecting both light and the gaze. The dress looks as if to defend its internal object, despite making the wearer irrelevant and unnecessary. The dress is a beautiful, terrifying suit of armor, but protecting what? Armor for whom?

Bill Brown, in his essay A Sense of Things, quotes Max Weber as Weber struggles with opacity and transparency in the acceptance of objects, saying “culture will come when people touch things with love and see them with a penetrating eye… it is only through things that one discerns himself.” The effort then, as Brown says, is to “penetrate them, to see through them, and to find… within an object… the subject.” He suggests that to understand a thing as not an object but a subject, not as something that is, but rather something that is being, a certain amount of willingness to surrender past materiality and physicality is necessary. We search for its origins, its opinions, its story. We look to tell our own stories through them. For most clothing, the task of this storytelling lies with the wearer, and we see through the clothing to understand the mind and the body it clothes. van Herpen’s dress cannot be a subject, nor does it allow subjectivity to a wearer, as we have no way of being able to see through it. As a piece, we know nothing about its origins. As a garment, we know nothing about its wearer. To imagine a dress like van Herpen’s that allows us to come within, I have created an alteration.

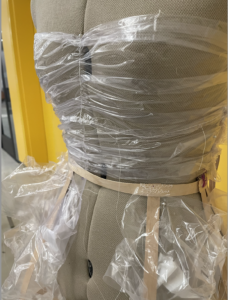

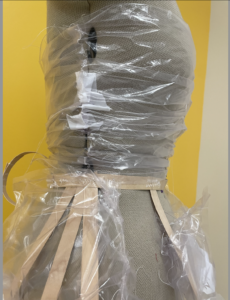

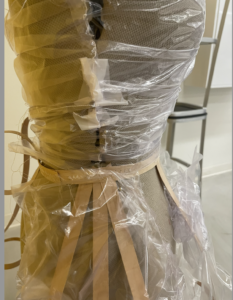

This altered piece uses contrast to converse with van Herpen. Where the construction of the van Herpen is indiscernible, this piece is full of visible threads, construction lines, and seams. The labor, the handicraft, is obscured in the van Herpen, as if it could be made by a machine. The altered piece is full of uneven lines, imperfect measurements, and human error, and in that, it is also personal. Where the material of van Herpen is proprietary, the material of this piece is quotidian. Both plastics, the proprietary PVC is inaccessible and highly coveted, whereas the Ziploc bags this piece was made with were purchased at a convenience store and often lay around houses forgotten, never special or exciting. Supporting materials in the van Herpen are silk and metal; supporting materials in this piece are wood and cotton, precious versus common. Where the van Herpen dress has clean, precise shuttered gill texture, this piece has imperfect, messy ruching texture. Finally, where the van Herpen is opaque, at every turn this piece is transparent. The see-through quality of the Ziploc bags show the scaffolding holding the skirt in place, exposing the way the dramatic shape is created. There is no notion of this in van Herpen’s piece. Where that piece gives us nothing acknowledging what has created it, the alteration openly tells you its whole story.

This altered piece uses contrast to converse with van Herpen. Where the construction of the van Herpen is indiscernible, this piece is full of visible threads, construction lines, and seams. The labor, the handicraft, is obscured in the van Herpen, as if it could be made by a machine. The altered piece is full of uneven lines, imperfect measurements, and human error, and in that, it is also personal. Where the material of van Herpen is proprietary, the material of this piece is quotidian. Both plastics, the proprietary PVC is inaccessible and highly coveted, whereas the Ziploc bags this piece was made with were purchased at a convenience store and often lay around houses forgotten, never special or exciting. Supporting materials in the van Herpen are silk and metal; supporting materials in this piece are wood and cotton, precious versus common. Where the van Herpen dress has clean, precise shuttered gill texture, this piece has imperfect, messy ruching texture. Finally, where the van Herpen is opaque, at every turn this piece is transparent. The see-through quality of the Ziploc bags show the scaffolding holding the skirt in place, exposing the way the dramatic shape is created. There is no notion of this in van Herpen’s piece. Where that piece gives us nothing acknowledging what has created it, the alteration openly tells you its whole story.

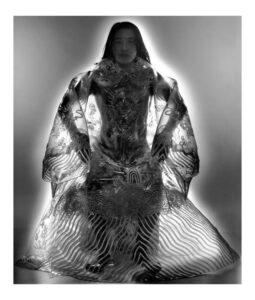

As evidenced in Wang Jin’s “Dream of China,” light is critical to enable transparency. Bill Brown’s concept of transparencies, voids and thingness offers us a way of thinking about this. “It is all those spaces within the inside of the chest, the inside of the wardrobe, the inside of the drawer that, by Bachelard’s light, enables us to image and imagine human interiority,” Brown says. In “Dream of China,” the way the light is cast gives us the image of the person within the garment, but also imagines their ethereality, the way their body interacts with the fabric, allows us to imagine who this powerful person is and what they desired in putting on this dress. The transparent gives us new frames for bodies, new narrative tools. For both van Herpen’s dress and the altered piece, light creates the white reflections on the surface, but van Herpen’s uses light to enhance obscurity. With the altered piece light is illuminative, allowing light through, allowing us to understand the body of the piece and the body beneath it.

As evidenced in Wang Jin’s “Dream of China,” light is critical to enable transparency. Bill Brown’s concept of transparencies, voids and thingness offers us a way of thinking about this. “It is all those spaces within the inside of the chest, the inside of the wardrobe, the inside of the drawer that, by Bachelard’s light, enables us to image and imagine human interiority,” Brown says. In “Dream of China,” the way the light is cast gives us the image of the person within the garment, but also imagines their ethereality, the way their body interacts with the fabric, allows us to imagine who this powerful person is and what they desired in putting on this dress. The transparent gives us new frames for bodies, new narrative tools. For both van Herpen’s dress and the altered piece, light creates the white reflections on the surface, but van Herpen’s uses light to enhance obscurity. With the altered piece light is illuminative, allowing light through, allowing us to understand the body of the piece and the body beneath it.

Brown’s insight also challenges us to think about spaces and voids. Both the van Herpen dress and the alteration struggle to defy gravity in creating warped sculptural space next to the body in the skirt of the dresses. The result is somewhat of a cage, harkening back to female fashions of hoop skirts and corsetry, constricting space the wearer is allowed to occupy. The van Herpan creates valleys on the outside of the dress, the alteration creating loops and protected spaces within. The emptiness of the spaces between fabrics and in these constructions feel vastly different: the van Herpan voids are places where light pools, and the voids in the alteration are where light, and the gaze, passes through into the space beneath, around, and under. This permissibility, this slippage, emphasizes the permeability of borders in transparent things. The lines between spaces, between object and subject, between the wearer and the world, are all challenged and altered.

This alteration is an attempted embrace of Weber and Brown’s concepts in the face of the questions Iris van Herpern’s piece forces us to grapple with. I attempt to create a vehicle of discernment, a way to see, within an object, a subject. That is fundamentally the work of the transparent. So often the transparent is conceptualized as lacking, as empty, as absence, and when it comes to clothing, insufficient. But transparent dresses are window panes, asking us to look through to find subjects in our objects and in turn, reframe ourselves.

Construction process

Close-ups of bodice, front

Completed side view

Completed back view

close-up completed bodice

(Images of final piece and works in progress by artist/author)

Works cited:

Brown, Bill. “A sense of things: the object matter of American literature.” University of Chicago Press, 2003, pp 7-11.

Images:

Personal image taken in the Met Costume Institute

Source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/701654

Artist: Iris van Herpen

Wang Jin, “Dream of China,”

Source: https://www.cobosocial.com/benjamin-sigg/wang-jin/