The Asian, Exotic, and Powerful in Alexander McQueen’s “Chinese Garden”

by Ina Aram

“In the end, we should be less surprised by the tenacity of this racial imaginary than by the limits of our response to it.” –Anne Cheng

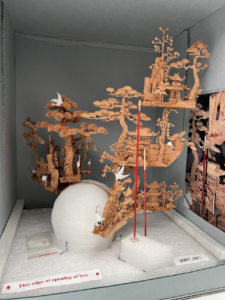

Come close and bend over. Hold your breath. To view Alexander McQueen’s “Chinese Garden” is to be a giant over a fragile world. At the The Met’s Costume Institute the headpiece rests in a cardboard box. The object’s intricacy is visible up close—oriental-style houses, decorative panels, tree tips, staircases. The headpiece is made of cork, and except for some white swan-geese, it is entirely monochromatic and unpainted. Stilts support the object and red letters demarcate the box’s edge for caution. So much as a pointing finger feels harmful around the village. Footsteps around the object make it shake.

The headpiece is fragile and damaged—a ziplock bag to the side of the object stores a minuscule detached piece of cork, and a dish in the corner of the box holds stray tree puffs. But the headpiece is also pretty, breathy, and amazing in its ornateness, precisely because of its fine details. Why was the headpiece designed using this fragile cork? How would the experience of the object change if it were made of a more durable material, like plastic or iron? And why was the scene stripped of color? The houses and trees seem drained, especially in contrast with the colored birds. When a model wears the headpiece on the runway, her matching beige hair is fixed in a way that supports the headpiece. The village seem to emerge naturally from her head. Ultimately, the object is pacified by its slight construction and hue. It cannot stand on its own. The houses, trees and rocky planes—the majority of the headpiece—give the feeling of being a background, while the birds, or maybe the headpiece’s wearer, stakes the foreground. What is the significance of the headpiece’s fragility and placidness?

Anne Cheng’s theory of ornamentalism can contextualize the headpiece as an object of Asian ornament in the Western gaze. “Asia is always ancient, excessive, feminine, open for use, and decadent…” (88) Cheng asserts, “there is no room in the Orientalist imagination for national, ethnic, or historical specificities.” The headpiece’s delicate cork and monochrome are symptoms and executions of the West’s notion of Asia. The object is designed in a code we understand: the hip-and-gable roofs. The bonsai trees. The geometric designs on partitions. The object does not need color or durability—both would be contradictory to the aura. We grasp the tone of the piece instinctively through its frail but peaceful and wispy shapes. It does not matter that the designer Philip Treacy conceived of the headpiece’s idea while in Kyoto, and it does not matter that the headpiece’s cork was imported from Japan—the piece is titled “Chinese Garden” and it makes sense. With the curvy trees and winged roofs and meditative cork, the label “Chinese” adds to the aura. This China-Japan superimposition is what Cheng identifies as China being “a cypher for a cypher” (88). The headpiece’s construction executes the West’s Asia fluently, and the monochrome is a nullifying varnish to the scene. If the trees were painted green, and the houses red and brown, the headpiece would be imbued with a reality it can exist without. Realism might distract from the mystical aura the piece’s blankness exudes. And if the piece were made from a sturdier material, it would reject the Western gaze of Asia as “open to use,” “decadent” and stereotypically zen. Plastic could be political. Iron might be stressful. And gardens like these are not stressful nor political, at least not in the Western consciousness. These gardens are relaxing. As it is, the object is easy on the eyes, something that would invoke in observers the monosyllabic, vowel-filled, pleasureful and breathy “Wow.” The object is approachable. When looking at it, there is some fantasy of shrinking to its miniature scale and wandering through its garden. It is a penetrable space.

It is easy to enter the scenery because of something else the object lacks: human life. There are no people in these houses, and no implication or connotation of people either. Imagine this headpiece were not made up of oriental-style houses, but houses plucked from a suburban American neighborhood. Imagine the white-picket fences, the driveways, and—really pushing it—some family dogs instead of the swan-geese. Why would these suburban homes imply life and story, whereas the current oriental arrangement conveys Asia as an aesthetic? We would wonder who lives in the suburban homes. We would wonder about the artistic choice to layer the homes in floating planes; the surrealism of the headpiece would warrant questioning, whereas with the oriental structures it is meshed with its mystical aura. And we would call the houses homes. With Western suburbia it might feel invasive to view the headpiece because of its implication of people and ownership. Personhood would be indivisible from the Western homes, whereas the rendering of Asian architecture as clothing accessory is swift. Whether due to the airy design of the headpiece, or Asia’s unfeasibility for specificity as Cheng asserts, the object is imbued with emptiness. This Asian landscape can exist without context—it can be an ornament to its wearer.

The headpiece’s lifelessness also comes from its fantasy. The headpiece is built upon imagination, on top of a head. Except for the plain headband, none of the headpiece’s cork structures would touch a wearer’s body. The piece’s construction as a floating headpiece renders Asia unfounded, theoretical, and of the imagination. The village grows in a surreal upward direction, which is outlandish but unfazing—the surrealism fits the mystical Asian aura. The piece’s separation from the body mirrors Asia’s distance from the West in its ornamentalism and exoticization. What if the design began at the wearer’s waist, with trees and structures wrapping upwards on the stomach and back, climaxing at two houses over the breasts? Maybe this iteration would evoke the theme of femininity. If these structures were footwear, a different story would be told, with themes of labor and power. But compared to these hypotheticals, when the design is placed atop the head as it is, the object lacks the background of the human. The headpiece and the Asia it depicts are alienated from the mainland of the body. This is a fantastical scene, some pretty place beyond our gaze and beyond human relevance.

You can never be quite level with this piece: when someone wears it, the object is likely above your eye-line, and when it is on a surface, you would have to bend low to observe it. The piece is three-dimensional. You can view it from one angle, but would need to walk around it to perceive all of its details, ultimately never grasping the object all at once. The object’s details are tiny. They beckon you closer to see, and once you are close, you can see the repetition of techniques to shave the cork into trees, into roofs. The closer you are, the less amazing the mystical illusion feels: it is just cork and cuts. What if the object were larger, not miniature and doll-like? What if more of it were perceivable from further away? But illusiveness is integral to the headpiece. The object challenges its viewers in its size, color, fantasy, and ornament. It makes you wonder what is there. “Illusive” may very well be a synonym for Asia’s tired “exotic.” However, this headpiece’s illusiveness is powerful, and something I want to amplify.

In thinking about the power of this object, I first want to ask, what distinguishes ornamentalism or exoticization from homage? What separates appropriation from appreciation? Could this headpiece simply be a commemoration of Asian aesthetic? The craft and detail in the piece is astounding, and clearly the object is not a careless production but a work of art. If there is an answer to these questions, it may be in the fact that the object lies on the head. Hats are more like jewelry than shirts or pants—they are accessory, not essential wear. And while hats can be functional, this headpiece is not. In fact it is the opposite: it requires help to stand. It is an accessory for aesthetics, for looking and not using. It is total ornament. The headpiece’s washed-out, fragile cork material allows it to be the relaxing, unassuming Asia for the West. I want to put pressure on this subjugation. Does the headpiece have to represent a feeble, accessorized Asia?

I want to imagine a glass alteration of “Chinese Garden.” Replace the cork with glass, and coat the glass with silver—mirrors will make this sanctuary transform into itself and whatever, or whoever, is around it. There will not be tiny shreds of wood scattered around the headpiece. No—if the object breaks, then all of it breaks. Glass is both less and more fragile. We have all of it or none. And if the glass breaks it will shatter. It will make a terrific sound. Glass and mirrors are essentially colorless, but morph into the colors around them. This chameleon-ing does not combat the issue of ornamentalism and objectification raised, but rather leans into it. We would observe this glass garden and see ourselves, see our own colors and features. The glass alteration would poke harder at the questions of appropriation and appreciation—the glass will interrogate us as viewers and interpreters. What effect do we bring to art with our biases and interpretations?

This cork headpiece is not weak. It is powerful—it commands the viewer. Come closer. Bend over. Look at me, and be scared to break me. In its glass alteration, the headpiece would be visually unsettling from afar. Something there and not there. Move closer and you would find the scene and its shapes as well as yourself. Let the sanctuary camouflage, mutate. Would you focus on the trees or your own image? How much of the garden would remain? How much of the headpiece is distinct enough to endure a total discoloration and dematerialization? What is left of this Asian space when its Western pacification is put to the extreme?

Works Cited

Cheng, Anne. Ornamentalism. Oxford University Press, 2019.

McQueen, Alexander. Chinese Garden. 2005, The Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Images taken at Met Costume Institute, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/128828?deptids=8&ft=chinese+garden&offset=0&rpp=40&pos=1. Artist: Alexander McQueen.