Madeleine’s Robe: Between Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and Goyo’s Woman Dressing

By Fizzah Arshad

“He made you over just like I made you over. Only better. Not only the clothes and the hair, but the looks and the manner and the words.” — Scottie

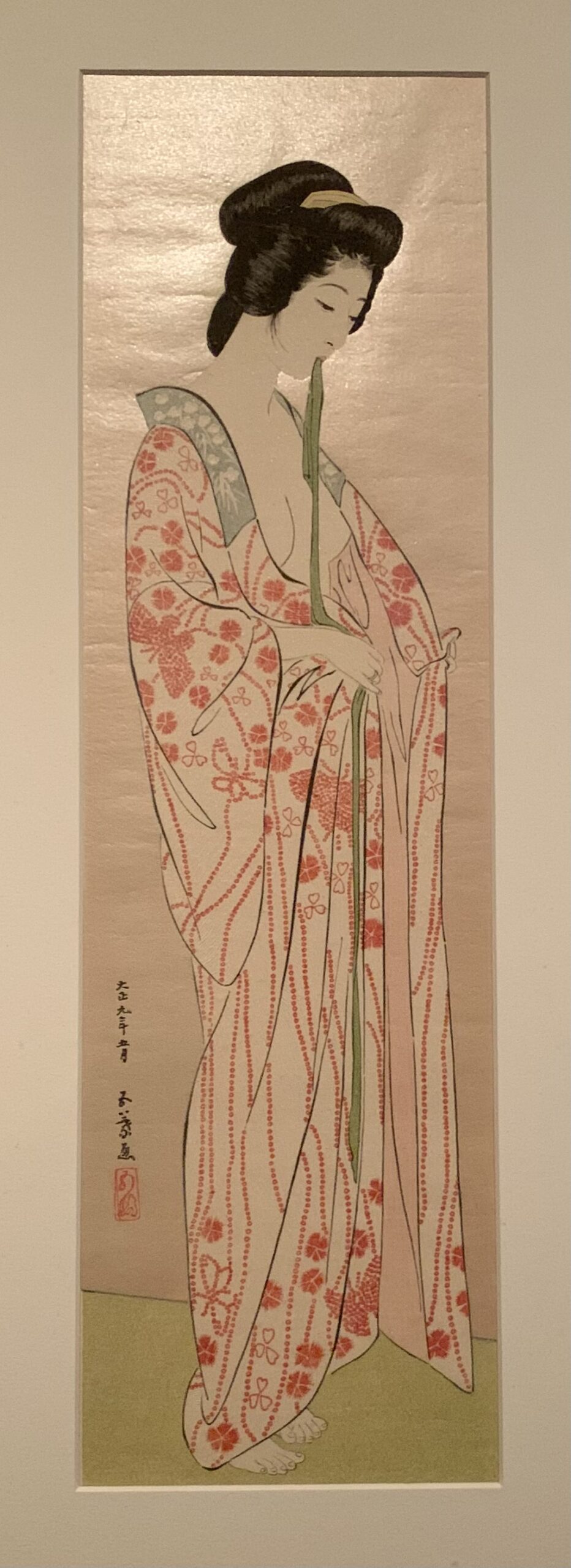

Among the works featured in The Met exhibit, “Kimono Style,” is Hashiguchi Goyo’s Woman Dressing. In this woodblock print, a woman ties her nagajuban, a robe worn under kimonos. The print is vertical and shines with mica (more visible in-person), highlighting the simple elegance of the muse. Considering also the red pattern and the woman’s updo, it is difficult to not think of Madeleine from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). The scene that particularly comes to mind takes place after Scottie rescues her from drowning in the San Francisco Bay. This scene is significant for two main reasons: It features the first interaction between Scottie and “Madeleine,” and is the first and only time Scottie is able to save her (or at least believe that he has). She awakes in his house, unclothed and with damp hair, and he offers her his red silk robe to wear. Enveloped in a stranger’s clothes, curled up in a stranger’s home, Madeleine appears to be the more vulnerable and unaware participant but in fact has the upper hand. Unbeknownst to Scottie, Madeleine’s jumping into the bay, her meandering drives, and her subsequent conversations with him are all contrived. Her power is palpable, for example, when she uses Scottie’s intrusive questions to flirt with him and to justify interrogating him in his own house. Later in the film, she acknowledges, “I want you to have peace of mind. You have nothing to blame yourself for. You were the victim” (110), taking responsibility for the murder and for deluding Scottie. For him, peace of mind of course never comes.

Among the works featured in The Met exhibit, “Kimono Style,” is Hashiguchi Goyo’s Woman Dressing. In this woodblock print, a woman ties her nagajuban, a robe worn under kimonos. The print is vertical and shines with mica (more visible in-person), highlighting the simple elegance of the muse. Considering also the red pattern and the woman’s updo, it is difficult to not think of Madeleine from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). The scene that particularly comes to mind takes place after Scottie rescues her from drowning in the San Francisco Bay. This scene is significant for two main reasons: It features the first interaction between Scottie and “Madeleine,” and is the first and only time Scottie is able to save her (or at least believe that he has). She awakes in his house, unclothed and with damp hair, and he offers her his red silk robe to wear. Enveloped in a stranger’s clothes, curled up in a stranger’s home, Madeleine appears to be the more vulnerable and unaware participant but in fact has the upper hand. Unbeknownst to Scottie, Madeleine’s jumping into the bay, her meandering drives, and her subsequent conversations with him are all contrived. Her power is palpable, for example, when she uses Scottie’s intrusive questions to flirt with him and to justify interrogating him in his own house. Later in the film, she acknowledges, “I want you to have peace of mind. You have nothing to blame yourself for. You were the victim” (110), taking responsibility for the murder and for deluding Scottie. For him, peace of mind of course never comes.

How might Judy be dressed if the scene was shown from her perspective, bearing in mind her mission? How does she assume Madeleine’s persona with such ease in front of others? Woman Dressing fills the gaps in the film: how Judy makes herself presentable behind the closed bedroom doors, to then emerge and resume her performance. My drawing takes inspiration from the design of the nagajuban in Woman Dressing. The resulting robe is one that better reflects how Judy mediates Scottie’s perception of her. The central adaptations from Woman Dressing are the styling of an updo before changing and coming out of the room, the reduction of red in favor of a blank ivory, and the addition of a green sash.

Dyeing and styling Judy’s hair is one of the crucial steps of making her over into Madeleine, who is never seen without her rolled updo. This scene is an exception. Her messy ponytail makes her guard seem down; for a moment she gazes into the fire with a hint of sorrow and loneliness. Is it a flicker of Judy or the doomed Madeleine? As soon as she fixes her hair into an adapted version of her swirled updo, her posture becomes more erect, her tone more assertive. Yet, despite the change in demeanor and the impression of vulnerability, Judy upholds the persona she has adopted from the beginning of the scene to the end. While her hair is down, she does not divulge any secrets, but does, however, milk the Carlotta Valdes ruse. For example, in an even more vulnerable state, sleep, she mumbles, “Have you seen my child?” (44:30), re-enacting Carlotta’s tragedy. Judy’s loose hair, then, is a red herring; it is as though she has been sporting her charged updo all along. Accordingly, the altered image has pins, and a mirror and hair brush set, so that in an alternative version of this scene, Madeleine not only covers herself with the robe, but coifs her hair before presenting herself to Scottie.

In the scene in question, a sort of exchange of personal colors occurs. Scottie, red, is in a green sweater and Madeleine, green, dons a red robe. Indeed, while both colors frequently appear alongside one another, such as in the wallpapered restaurant, Scottie’s vertigo is depicted in red. In contrast, green follows Madeleine, or more precisely, the illusion of Madeleine, through her car, clothing, and even the garden she wanders through. The exchange of colors expresses a transaction or connection between the two. But the basis for this is a falsehood: Scottie’s sense of his own heroism more so than legitimately saving Judy’s life. Therefore red in my drawing is minimized, and relegated to Carlotta’s necklace and the sash. Through both the necklace and the spiral motif in general, Judy effectively embodies Madeleine—the femme fatale. Further, by leaching red out of the robe, what remains is a color akin to Madeleine’s platinum blonde hair.

Madeleine, or Judy, is always most green when she is “reincarnated.” After Madeleine is publicly deemed dead, Judy appears walking on the street in a startling green set, head-to-toe (1:31:50). And even more notably, when Judy at last dons the signature gray suit she has been resisting, “becoming” Madeleine again, an eerie green aura pervades the room (1:55:38). Waking up after having plunged into the San Francisco Bay is too a sort of reincarnation, necessitating some presence of green which is absent in the original robe. By selecting green for the sash in the altered image, Judy is figuratively wrapped in the mirage of a living Madeleine.

The act of putting on undergarments or loungewear is quite different from that of putting on clothes for the day. It is private, intermediate, and less anxiety-inducing, as those garments are not for the public eye. Though the dimensions and sweeping patterns of Goyo’s Woman Dressing compel vertical eye movement along the subject’s body, her expression remains serene and poised. The subject seems unaware of the voyeurism that Judy in Vertigo is made to anticipate and even elicit from her position of seductive power. Indeed, Judy forms Madeleine’s first impression when she steps out of the bedroom “dressed” and Scottie gazes at her admiringly. Judy is fashioned into Madeleine; Madeleine is fashioned into Carlotta; Judy is fashioned into Madeleine yet again. It is within all these restraints that the Madeleine who wears the altered robe is in control. Only she is capable of misleading Scottie, whether or not she is falling in love with him. Even though the alteration of the robe is done to better express and emphasize Judy’s power and Madeleine’s aura (translated from mica to a glitter pattern in the drawing), the artist becomes complicit in the scrutiny and policing of Judy’s body. Through the exercise itself of picking apart the robe—the simplest garment Judy wears, her treatment in the film of and by others is modeled.

Works Cited

Coppel, Alec and Samuel Taylor. (1957). Vertigo [PDF Screenplay]. https://www.scriptslug.com/assets/scripts/vertigo-1985.pdf

Goyo, Hashiguchi. Woman Dressing, 1920. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Hitchcock, Alfred. Vertigo. Paramount Pictures : Alfred J. Hitchcock Productions, 1958.

Image from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/44586. Artist: Hashiguchi Goyo.

I pledge my honour that this paper represents my own work in accordance with University regulations. x Fizzah Arshad.