Fabric/Flesh: On Synthetic Flesh, Black Cyborg, and Miyake’s Bodice

by Anurag Pratap

Suppose you do change your life.

& the body is more than

a portion of night– sealed

with bruises.

— Ocean Vuong, “Torso of Air”

In Rupert Sanders’ The Ghost in the Shell, Asiatic femininity comes to congeal upon (and beneath) Major’s fabricated epidermal surface, animating in consequence a tired narrative of posthuman ontology that is inextricably about the human. If Major as a cyborg allows us to imagine the fabrication of whiteness through the crucial aesthetics of racialized personhood, this imagination lingers perpetually on the Asiatic. Yet, a brief scene draws us towards the crucial task of parsing out this imagination as not a binary of white/Asian, but as a triangulation where Black femininity lingers as a haunting sister of Asiatic femininity. It clear that this scene– wherein Major touches and examines intimately a “human” prostitute who is a black woman –rehearses modernity’s pivotal dependence on the racialized other to animate its own definition and ontology. Alongside, it recapitulates that in the future where everything is Asian, it is the black body that cannot be the cyborg; it is laden with its historical connotation of fleshly corporeality, reproduction, and animality. Though generative in evaluating the racial logic that comes to condition the visual imagination of skin, the critique fails to account for a series of questions the scene generates: who is the object and subject of the gaze? Though the framing centralizes Major’s tactile and sensorial investigation of the prostitute, it is the human-cyborg-prostitute herself that asks “what are you”? If this a scene of “obvious” fetish, who’s lack is being projected– does Major mourn biological, organic, fleshly body or does the prostitute in her own interrogation of Major mourn an alternative cyborg/synthetic ontology? Finally, if Major has the ghost of a Asian girl, who is probing and conversing with the Black body– the shell (whiteness) or the ghost (the Asiatic)?

In this muddled mirroring, we can read into the black female body a rehearsal of an alternative form of belonging, personhood, and even citizenship that references a synthetic form of ontology that has forever been a priori to Asiatic personhood. In a movie infused with all cyborgs, there are only two characters who retain their “organic” bodies: the black female body and the Asian mother. Not only is it clear that one references the other in the implied logic of reproduction (historical for the black body, and through maternity for the Asian mother), but each also retains a marginalized citizenship in the socioeconomic framings of this technological future. For the Asian mother, this visible in the spatial-organization which evokes of tenement and public housing; for the black body, it forms literally through her evocative reference to sex labor, alley-work, and clandestine space that surrounds her. Enhancements on the other hand offer mobility, power, and crucially citizenship in the cosmopolitan society of the movie– we are reminded of this already in the opening conversation between the African statesmen and Hanka operative wherein technological enhancements become the central currency in political practice. Against this intersection between technology, aesthetics, and politics, the surface of prostitute becomes laden then with an alternative mode of belonging. If the modernist imagination forever considers and operates with a visual demand for this surface as flesh, the black human-cyborg-prostitute responds by providing an alternate mediated surface which creates its flesh as a synthetic aggregate. Indeed, the surface of the black female is anything but flesh: the gelatinous patches create a visual and striking reminder of a face as collage, often even appearing to be seamless with the skin under the streetlight. The eyelash patterns though capable of separation, still in their sticky texture pull the “actual” skin with them. Herein, then the black female practices a form of visuality that blurs its surface and epidermis, giving an alternative story rather than the promised organic flesh. If Major has arrived to view what organic human ontology looks like, the human-prostitute-cyborg displaces this gaze onto the materiality which forges her visual surface. The camera never provides us with a bare skin surface, but a hyperattentive and specific close-up onto the materialism that is the extension (even the substance) of her skin. Even in the aftermath of her prosthetic removal– the “bare face”, a momentary cypher for the denuded body which might excite and offer Major her answers –the camera zooms out, reminding us how much of the denuded body still remains clothed in fabric. There are no easy answers for whom the black body responds to or asks “what are you” in this scene. Yet, I wonder if this body speaks to the ghost? In silence of the ghost and that of the black body itself, does a language of momentary solidarity arrive, a language of afro-asian contact– each recuperating their decorporeality not through emphasizing an organic “individualistic” flesh, but rather the materiality that forges it?

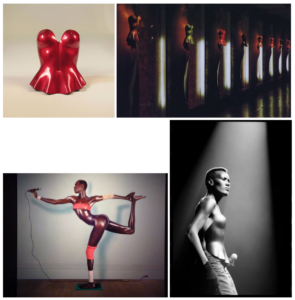

What is imaginative and hypothetical in Saunders, is literalized in the world of Issey Miyake. Devoid of cybernetics and cyborgs, Miyake’s pieces still offer and promise a modern, sculptural logic of fabrics and fashion. In his “Bodice” (1980-81)– a part of the BodyWorks exhibition –we can arrive towards a broader philosophy of flesh-as-fabric-aggregate, and its promises for the racialized body. Though the bodice and its associated references to armor, corset, and feminine form have had continued fascination (from Alexander McQueen, Yves St. Laurent, Scognamiglio etc.), Miyake’s bodice instead evokes an alternative narrative. What is figurative and abstract in other bodices– the flesh and femininity as wearable, detachable, and theatrical –-is literal in Miyake: it is unclear where the flesh begins and transforms into frock, and where the frivolous peplum frock merges into utilitarian athletic physiology. Already we have arrived at a similar observation as Saunders’ black prostitute: the fabric inherently here is an aggregate and composition of flesh, and the denuded surface cannot be extrapolated away from the fabric. Even when Miyake forces us to engage with these as not dresses but fixtures, the essence of a corporeal form and body still haunts us: the light frames an imaginative contour around it, perpetually reminding us of the potentiality of life, if not life in itself. Though the piece would be largely presented as fixtures in retrospective shows across the years, it is the model and actress Grace Jones– a frequent wearer of the piece –that helps us inform cleanly the potential of this dress. If Jean Paul Goude’s photograph of Jones excavate a modernist desire that desperately craves for a black feminine flesh which is both corporeal and “primitive” (noticing the primitive rehearsals in the photographs) and a commodity (in its evocation of “celebrity”, but even concretely in referencing commercial items), Miyake’s pieces offer an escape for Jones. In its eerie similarity to flesh, Miyake offers for Jones a surrogate surface. Miyake’s dress both satisfies the desire for flesh and critiques it (in emphasizing its materiality). What is implicit in the dress– an offering and potentiality of life that does not require the human body and flesh –-transforms it into a vital medium of escaping visuality. We do not get the “raw” skin, but a surface which is fused with an imagined, “idealized skin”. The bodice does not reconstitute flesh, but offers an opportunity for that flesh to escape the visual focus in replacing an alternative fabric-as-flesh in our ocular focus.

What is imaginative and hypothetical in Saunders, is literalized in the world of Issey Miyake. Devoid of cybernetics and cyborgs, Miyake’s pieces still offer and promise a modern, sculptural logic of fabrics and fashion. In his “Bodice” (1980-81)– a part of the BodyWorks exhibition –we can arrive towards a broader philosophy of flesh-as-fabric-aggregate, and its promises for the racialized body. Though the bodice and its associated references to armor, corset, and feminine form have had continued fascination (from Alexander McQueen, Yves St. Laurent, Scognamiglio etc.), Miyake’s bodice instead evokes an alternative narrative. What is figurative and abstract in other bodices– the flesh and femininity as wearable, detachable, and theatrical –-is literal in Miyake: it is unclear where the flesh begins and transforms into frock, and where the frivolous peplum frock merges into utilitarian athletic physiology. Already we have arrived at a similar observation as Saunders’ black prostitute: the fabric inherently here is an aggregate and composition of flesh, and the denuded surface cannot be extrapolated away from the fabric. Even when Miyake forces us to engage with these as not dresses but fixtures, the essence of a corporeal form and body still haunts us: the light frames an imaginative contour around it, perpetually reminding us of the potentiality of life, if not life in itself. Though the piece would be largely presented as fixtures in retrospective shows across the years, it is the model and actress Grace Jones– a frequent wearer of the piece –that helps us inform cleanly the potential of this dress. If Jean Paul Goude’s photograph of Jones excavate a modernist desire that desperately craves for a black feminine flesh which is both corporeal and “primitive” (noticing the primitive rehearsals in the photographs) and a commodity (in its evocation of “celebrity”, but even concretely in referencing commercial items), Miyake’s pieces offer an escape for Jones. In its eerie similarity to flesh, Miyake offers for Jones a surrogate surface. Miyake’s dress both satisfies the desire for flesh and critiques it (in emphasizing its materiality). What is implicit in the dress– an offering and potentiality of life that does not require the human body and flesh –-transforms it into a vital medium of escaping visuality. We do not get the “raw” skin, but a surface which is fused with an imagined, “idealized skin”. The bodice does not reconstitute flesh, but offers an opportunity for that flesh to escape the visual focus in replacing an alternative fabric-as-flesh in our ocular focus.

From Saunders’ human-cyborg-prostitute to Miyake’s Bodice, we arrive at a narrative of fashioning as flesh formation, of offering a material and artificial body that is neither organic nor “authentic”. Moreover, this surrogate-skin formation unintentionally or intentionally arrives at a site of afro-asiatic contact: whether it is psychical and imaginative in Saunders, or literal in Miyake’s collaboration with Grace Jones. However, these pieces each come to offer us a surrogate surface which inherently remains tied to femininity. If from Freud to Ocean Vuong, we have begun to excavate queerness as a perplexing and deeper conversation about interiority, surface, essence, and ontology, what does this logic of fabricated flesh as surrogate offer us in regards to that conversation? What does it mean for the surface of Miyake’s dress to not replace the commodified, organic flesh of a female body, but that of a queer and trans person? In engaging with this question in my alteration, I want to emphasize this surrogate surface as not a frivolous concern, but a necessary means of personhood. A personhood that through its rehearsal of patriarchal narratives and commodity culture manages to carve an ontology inherently suffused with artifice. Fabric as synthetic flesh offers us not simply a narratology of joyous escape from ocular and fetishizing gaze; instead for queer people, this materiality and adornment is a necessary means to restructure pain and construct an alternative ontology.

This represents my own work in accordance with the Honor Code — Anurag Pratap

Images:

Alteration:

Salman Toor, “Immigration Men” (2019).

Issey Miyake, “Bodice” (1980-81). Image from: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/675703

Irving Penn (Photographer). “Billowing Pleats” (1985). Campaign Ad for Issey Miyake.

Yiorgos Mavropoulous (Photographer). Title Unknown. For “XXIst Century Man” (2008) by Issey Miyake.

Panel 1:

Screenshots from The Ghost in the Shell (dir. by Rupert Sanders), Paramount Pictures, 2017. Taken by the author.

Panel 2:

Issey Miyake’s “Bodice” (1980-81). Image from: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/675703 (top left); Issey Miyake’s BodyWorks Exhibition, Tokyo, Japan (1983). Credit to respective photographer. (top right); Jean-Paul Gaude’s “Grace Revised and Updated” (1978). Credit to respective artist. (bottom left); Grace jones performing in Drury Lane Theatre, London (1981). Credit to respective photographer. (bottom right)