Summary:

Traditional models show that Asians are not well-represented in politics: Asians have historically had an abysmal turnout rate, and even in regions with substantial Asian cultural integration, there is little direct representation or interest articulation. The combination of these three phenomena seems to generally prevent Asians from being politically well-integrated in the United States. In CA-19’s San Jose, however, the traditional model seems to not apply. Asian voter turnout in San Jose is relatively high, due to concentrated efforts by Asian advocacy groups to increase turnout and political engagement. In addition, there are also a fair number of Asian representatives in California generally and San Jose specifically. Despite subverting the traditional model, however, San Jose still seems to struggle in adequately representing Asian voters’ interests. While the Asians interviewed in a small-scale study voted consistently in presidential, state, and local-level elections or frequently participated in political activities like campaigning or fundraising, their political interests were not represented by their party or in politics generally. Moving forward, San Jose’s political representatives at every level should listen more carefully to their Asian constituents: that is, understanding and addressing their many political interests through open lines of communication.

CA-19: The Limitations of Asian Political Integration in San Jose:

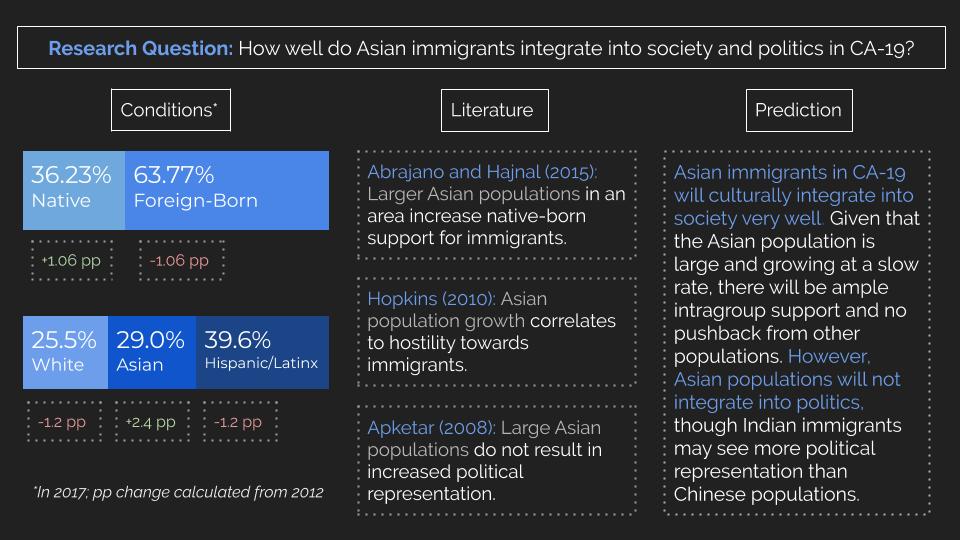

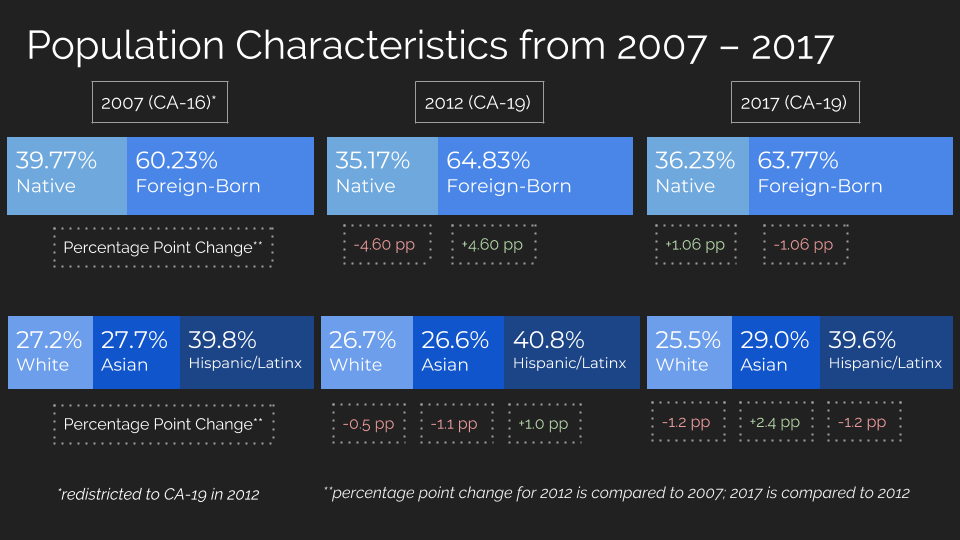

May marks the beginning of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, a month in which we celebrate the culture, traditions, and history of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States. The month is particularly well-advertised in San Jose: take a walk around the city, and you’ll see flyers and posters announcing the month in schools, restaurants, malls, and every other possible public space. This is not an inexplicable phenomenon, given the city’s Asian population size: while Asians are currently 5.6% of the U.S. population, AAPIs account for 15% of Californians and 30% of San Jose residents. Since San Jose serves as a population hub for Asian-Americans, it is not difficult to imagine that it would also serve as a political haven: in theory, while places in the United States with fewer Asians might not represent the group politically, in San Jose, where Asians make up 30% of the city’s population, they should be well-integrated into politics through direct representation, voter turnout, and interest articulation. This, unfortunately, is not the case. While traditional models of Asian political behavior do not predict Asian behavior in San Jose, representatives in the city – congressional, state, and local – still do not adequately represent their Asian constituents’ political interests.

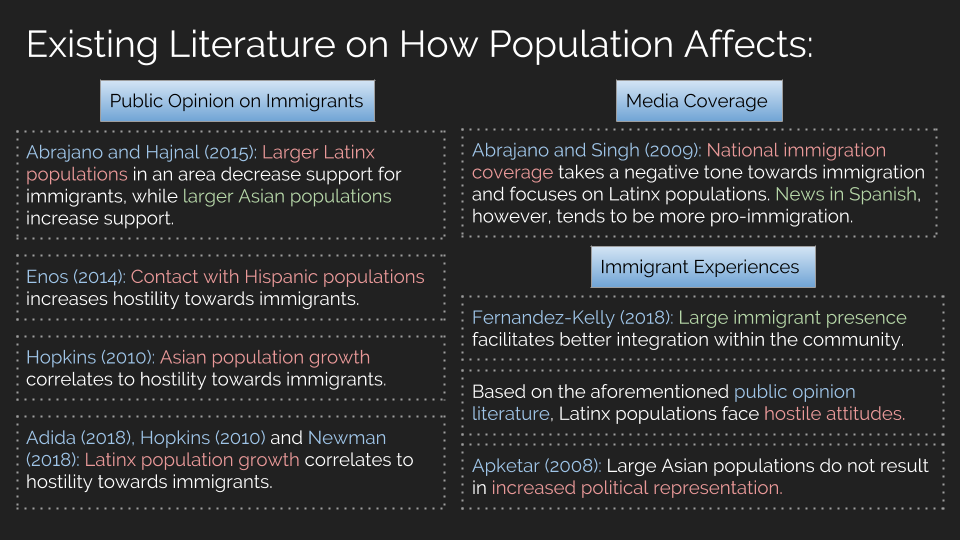

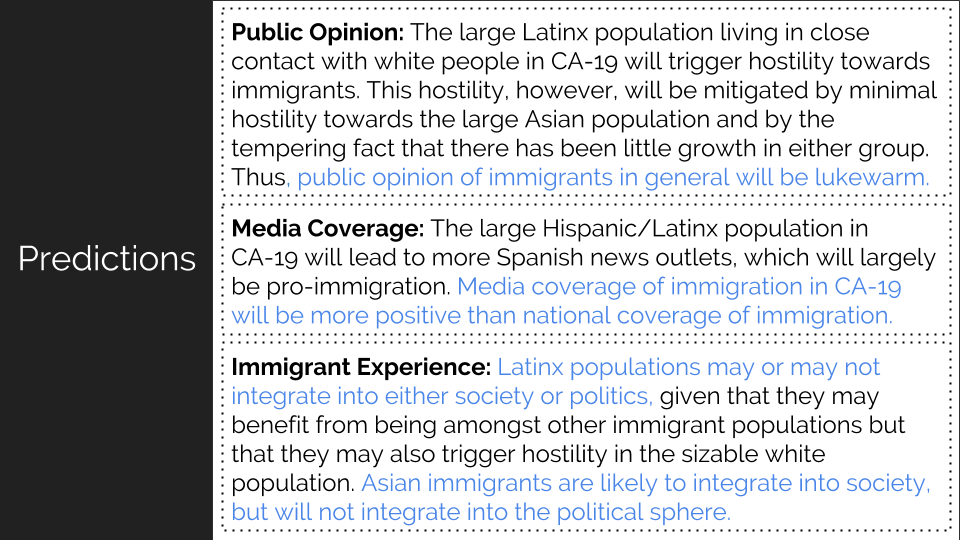

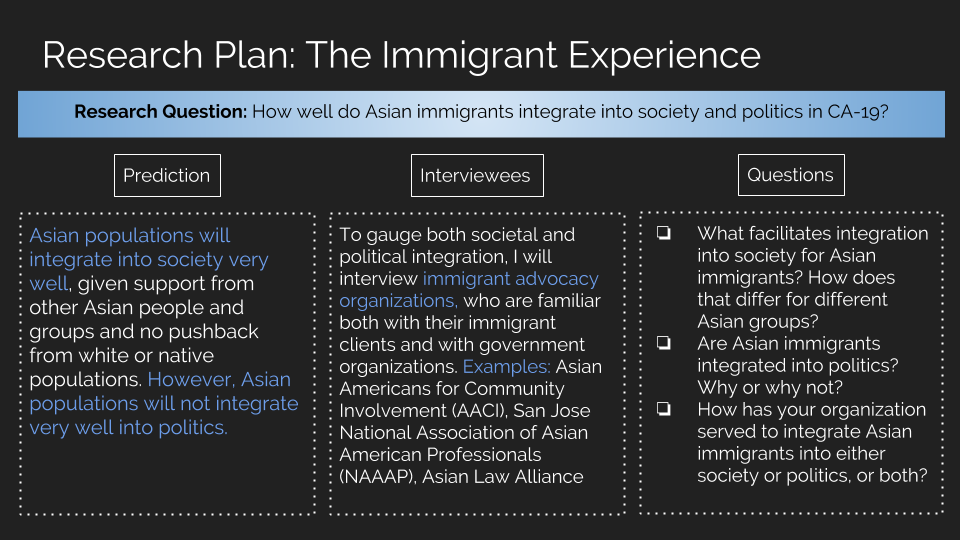

Traditional models of Asian political behavior show that Asians are not well-represented in every possible way. Asians have historically had an abysmal turnout rate: in the 2016 election, 49% of Asian voters cast ballots, as compared to 64% of White voters and 59% of Black voters, and even that was considered abnormally high. Moreover, even in regions with substantial Asian cultural integration, there is little direct representation (i.e. Asian politicians) or interest articulation. One study by Aptekar (2008) finds that despite a large number of Asian cultural organizations in suburban Edison, New Jersey, few Asians hold elected positions in the region and political elites are largely unaware of Asian political interests. The traditional model would thus suggest that a combination of low voter turnout rate, little direct representation, and lack of interest articulation that prevents Asians from being politically well-integrated.

In San Jose, however, the traditional model does not apply. Asian voter turnout in San Jose is relatively high, due to concentrated efforts by Asian advocacy groups to increase turnout and political engagement. Pastor, Rosner, and Tran write that in terms of immigrants generally, Santa Clara County has consistently exceeded or tied with Los Angeles County and New York City in terms of foreign-born voters. This, in large part, is because of inter-networked advocacy groups that encourage immigrant turnout, like the API Justice Coalition, headed by Asian Americans for Community Involvement (AACI) in combination with the Asian Law Alliance, the Asian Pacific Bar Association, and the Japanese American Citizens League of San Jose. In addition, there are also a fair number of Asian representatives in California, and San Jose specifically, which is a historical trend that has continued into the present day. A study by Pei-Te Lien found that in 1998, around 400 people of Asian or Pacific Islander descent held key elective positions in federal, state, and municipal governments, and 33 percent were from California. Today, direct political representation of the Asian population occurs to a great extent in San Jose specifically. Pastor, Rosner, and Tran explain that San Jose elected the first Asian-American mayor of an American city, Democrat Norman Mineta, in 1971. Since then, several San Jose Council members, like Madison Nguyen of District 7, have served on school boards and launched political careers. In addition, many of the other fourteen cities in Santa Clara County have elected Asian leadership. Cupertino has three Asian council members (a majority) and an Asian former mayor. Campbell, meanwhile, elected Evan Low, the first gay Asian council member, who has since gone on to serve as the mayor of the city and a member of the California State Assembly.

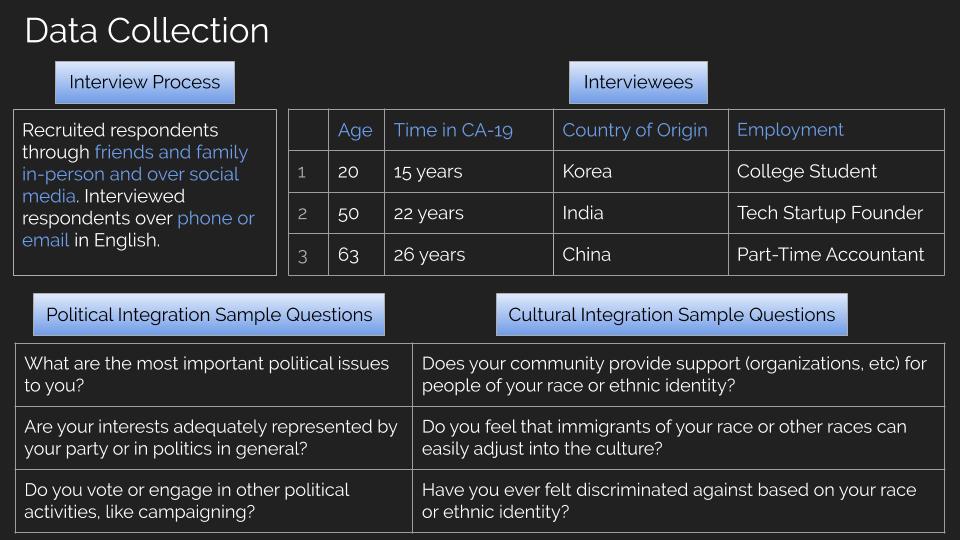

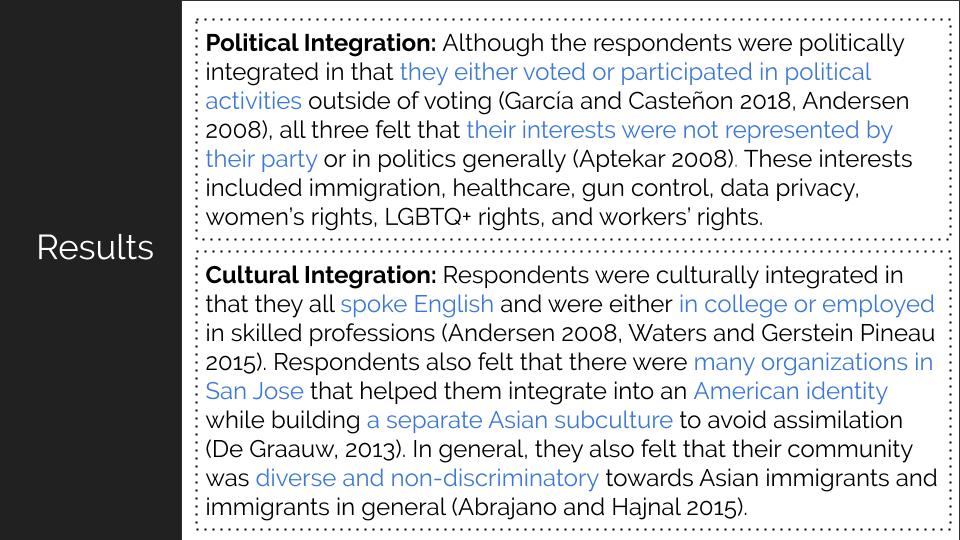

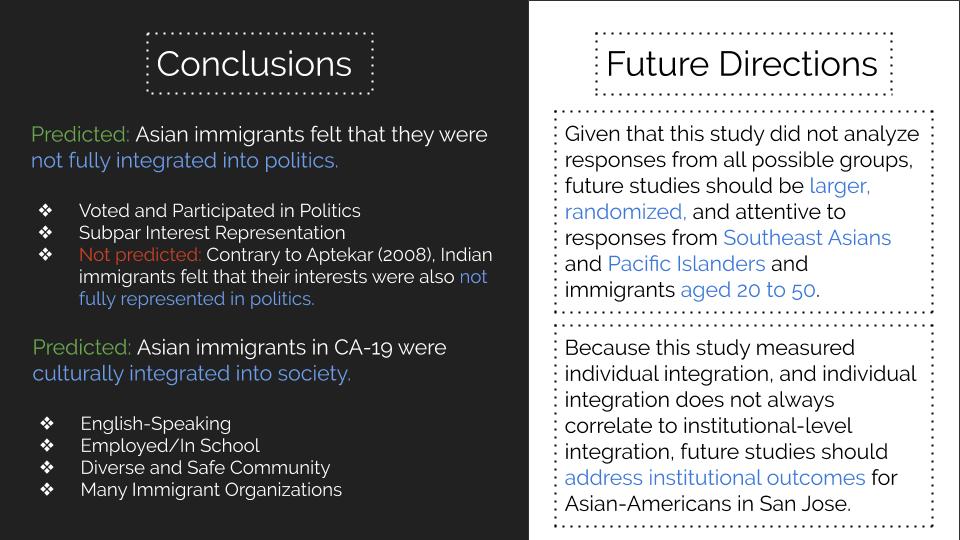

It is thus clear that San Jose does not struggle with the traditional difficulties of low Asian voter turnout and meager direct representation. The issue that San Jose seems to struggle with, however, is interest articulation. I interviewed three San Jose residents of differing ages, educational levels, and nationalities as part of a small-scale study on Asian immigrant political and cultural integration. All three said that while they voted consistently in presidential, state, and local-level elections or frequently participated in political activities like campaigning or fundraising, their political interests were not represented by their party or in politics generally. All three expressed intense dissatisfaction with the fact that their representatives, both national and local, did not frequently discuss or comprehensively flesh out positions on their interests, which included immigration, healthcare, gun control, data privacy, women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, and workers’ rights. While the feeling of inadequate interest articulation may be a sentiment felt widely in our current political arena, political elites’ habit of not listening to Asian constituents specifically is a well-documented phenomena, as Aptekar showed. San Jose’s political sphere, despite having good turnout and spectacular Asian representation, is thus still not representative of Asian voters’ interests.

What, then, do San Jose’s representatives need to do? It is evident that San Jose has thus far done a great job of subverting traditional expectations of Asian political behavior, with advocacy groups that promote turnout and a fair amount of direct political representation. Moving forward, San Jose’s political representatives at every level should listen more carefully to their Asian constituents: that is, understanding and addressing their many political interests through open lines of communication. This, of course, is a difficult job: translating symbolic representation into actual representation is difficult because the name “Asian” comprises more than a few nationalities, languages, beliefs, cultural norms, and backgrounds. That being said, however, San Jose representatives’ work is not yet complete. This May’s Asian American and Pacific Islander Month is a perfect time to enjoy San Jose’s many cultural offerings while understanding that the political needs of San Jose’s Asians haven’t yet been met.