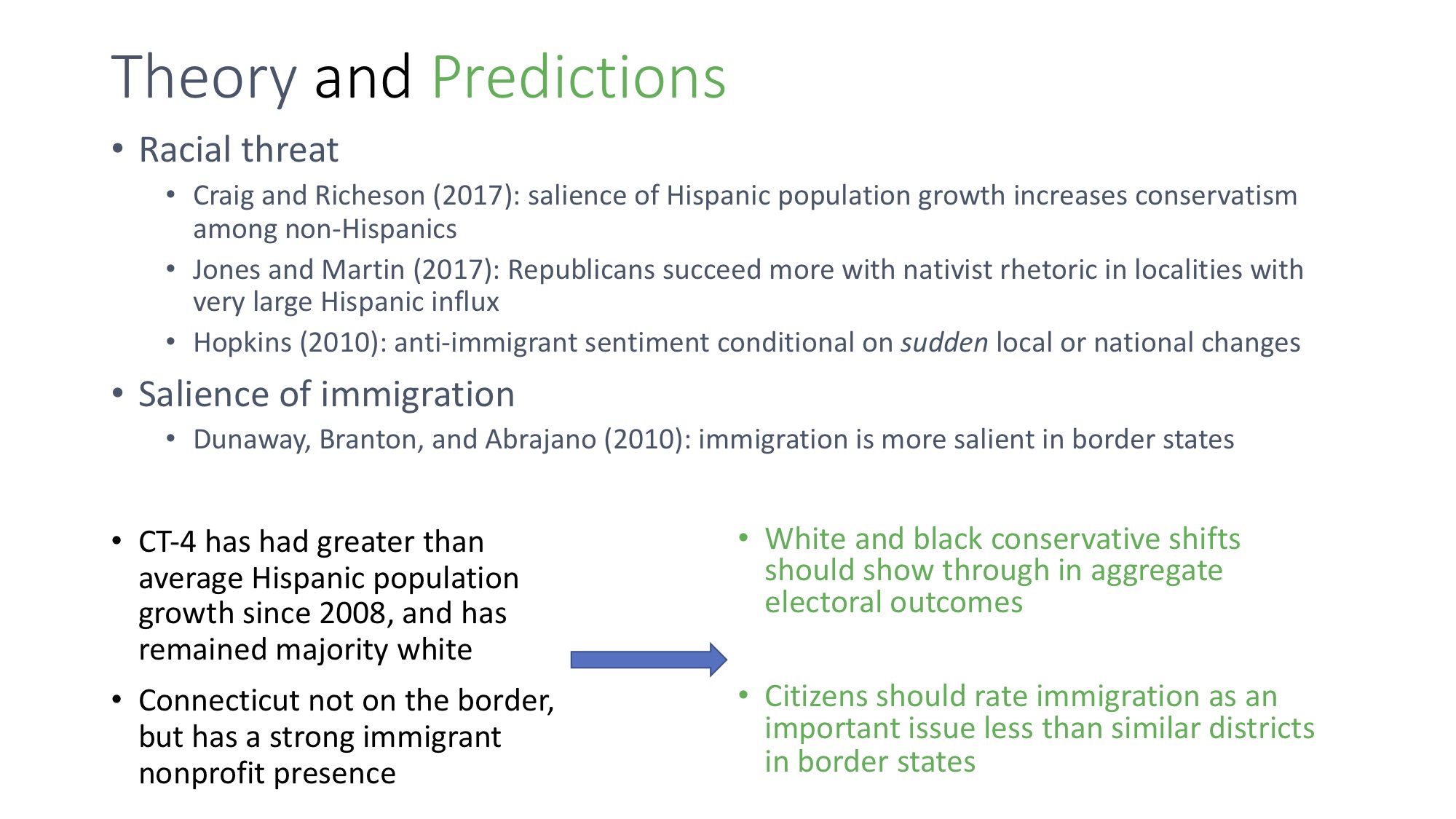

I. Theory and Predictions

I test the effect of CT-4’s demographics on two outcomes: electoral outcomes and the importance of immigration to voters. Many papers (more than mentioned in the slide) have documented “racial threat,” or the tendency of whites to become more politically conservative when faced with the influx (or economic rise) of racial minorities. The papers listed in slide 1 identify particular effects, which are in fact much more conditional than the general trend of racial minorities triggering white conservatism. Craig and Richeson (2017) randomized priming of respondents with newspaper articles about the growth of the Hispanic population (or a control condition). Jones and Martin (2017) set a very large cutoff (>300%) for Hispanic growth, and Hopkins’ (2010) “politicized places” theory argues that a large influx influences political outcomes and attitudes mostly during intense national news cycles, and not in general. We should be cautious, then, about drawing a general connection between non-white Latino immigration and white conservatism; it seems that only when immigration is at the forefront of respondents’ minds does it have an effect on their politics. The second outcome is simply how much immigration matters to survey respondents. Dunaway, Branton, and Abrajano (2010) show that border states exhibit higher immigration salience in both local media coverage and survey respondents’ attitudes.

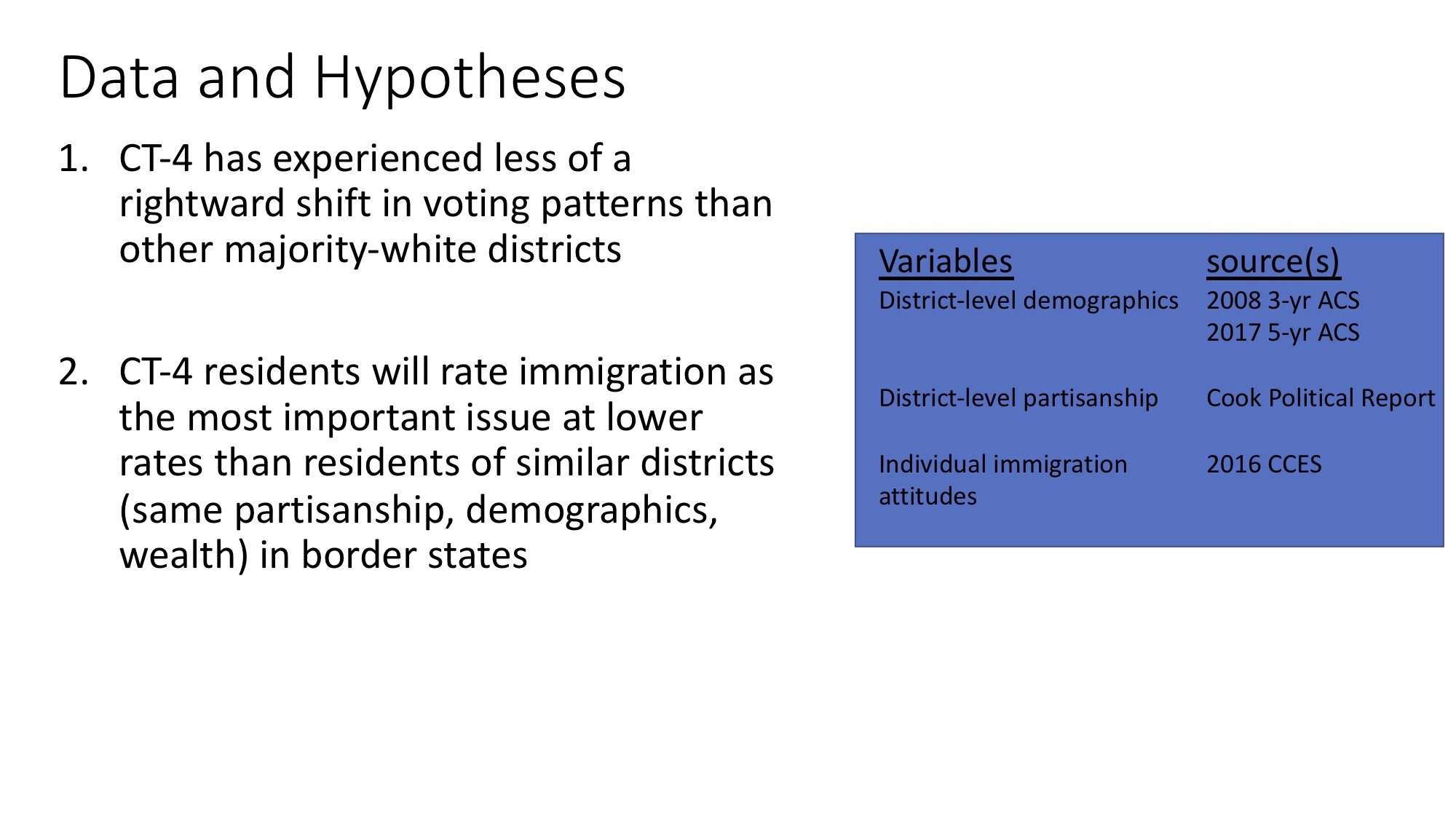

II. Data and Hypotheses

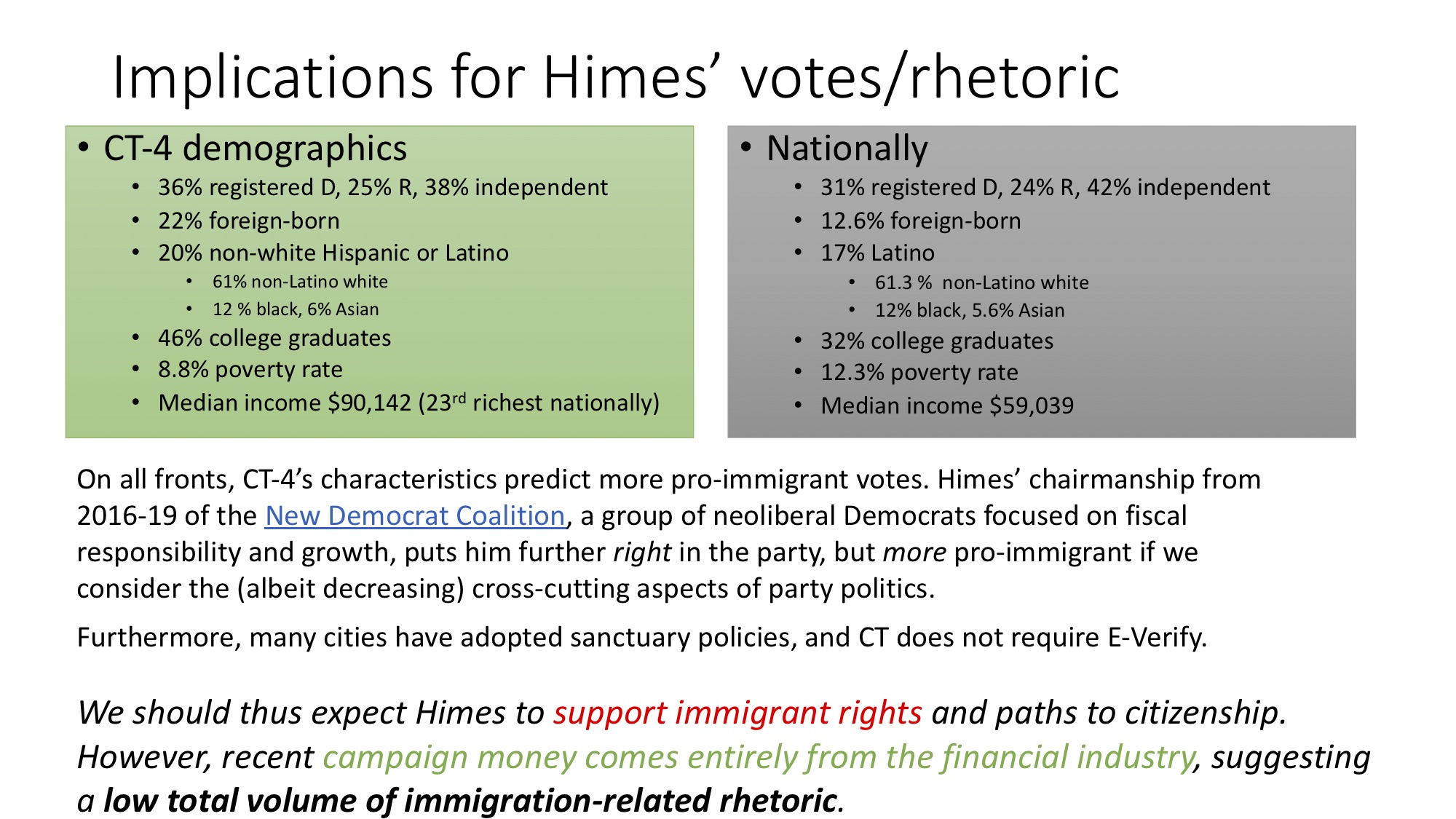

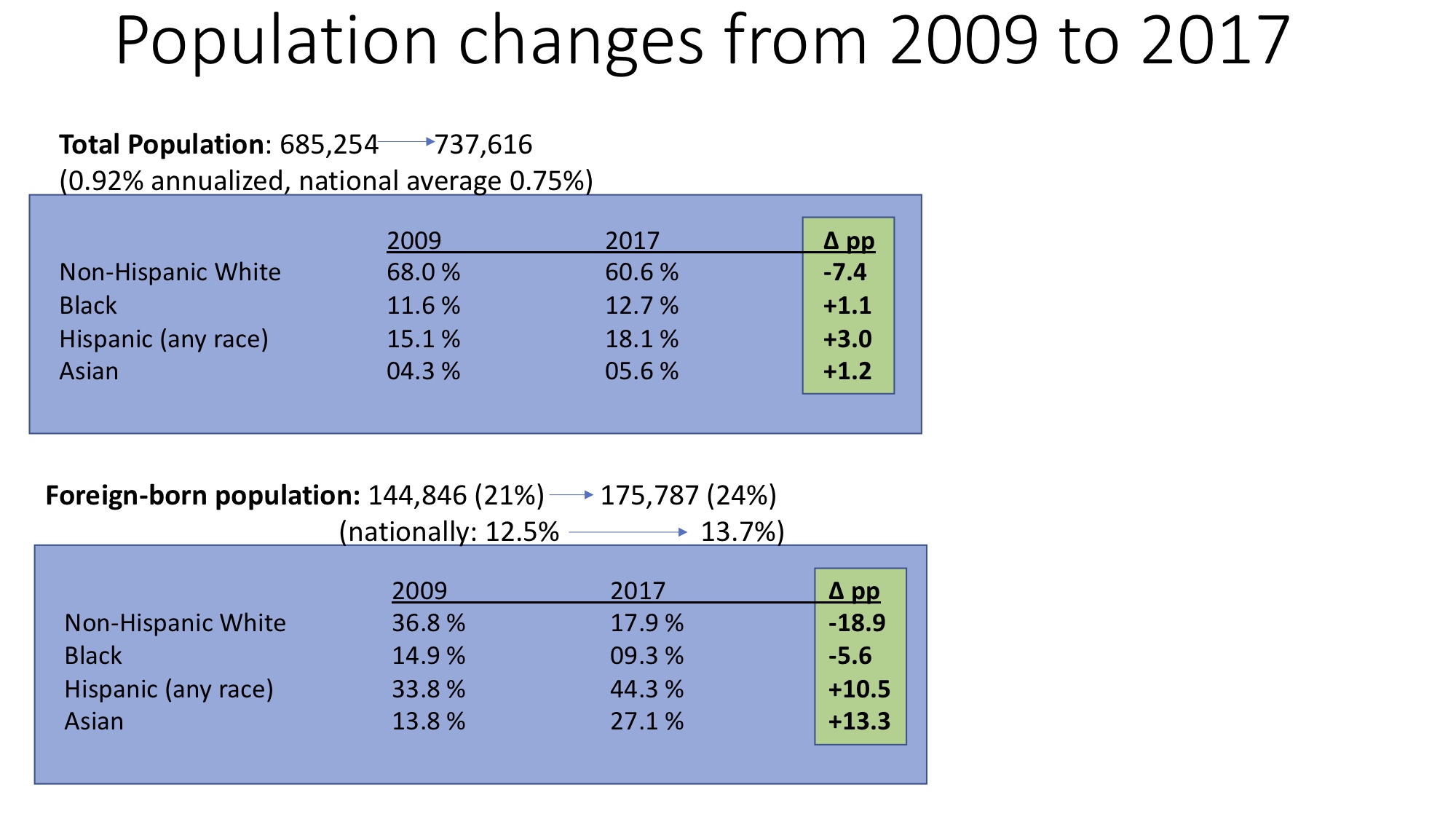

Because CT-4 has experienced greater-than-average Hispanic population growth since 2008, we might expect some white conservative shift in electoral outcomes. Such a finding would in fact fly in the face of the theories presented above because there is no activating mechanism like priming or a national emergency. Gathering data from the Cook Political Report (links below) and the American Community Survey (2008 3-year estimates, 2017 5-year estimates), I test the relationship between change in non-white Latino population (2008-2017) and change in Democratic vote share (2018 minus 2008), hypothesizing a negative relationship for majority white districts. Because CT-4 is majority white, but it did not experience “massive change,” it should fall above the line of best fit between these two variables. With respect to immigration salience, I use survey data from Harvard’s 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study. Using ACS data to identify very similar districts to CT-4, I ask if Dunaway et al.’s findings apply to districts like CT-4 in particular; if they do, we should witness a significant difference between respondents’ attention to immigration in matched districts in border states and their attention in CT-4.

III. Results: H1

I excluded all districts that had uncontested elections in either year, because electoral margins of 100% do not accurately reflect district-level partisanship. The bivariate plot in slide 3 shows the positive relationship between Democratic gains (∆pp) and percentage change in non-white Latino population growth (outliers mostly in FL and CA) for minority-white districts. This relationship is very significant (p < 0.005), but the coefficient for non-white Latino growth is not significant at any level for majority-white districts. Rather than the negative relationship we expected, it seems changes in Democratic vote share cannot be explained better by non-white Latino population changes than by a guessing the average. We do see CT-4 above the line of best fit as hypothesized, but that difference from the prediction is not due to the fact that its change in non-white Latino population was not sufficiently extreme; were that the case, the regression would be significant. Instead, I would ascribe that result to randomness, or even better to the massive number of other factors that influence electoral outcomes. Many traditionally Republican households in the northeast flipped blue in response to Trump, for example. In conclusion, we fail to conclude that a non-white Latino influx had any effect on district-level electoral outcomes, either for CT-4 or for non-majority-white districts in general.

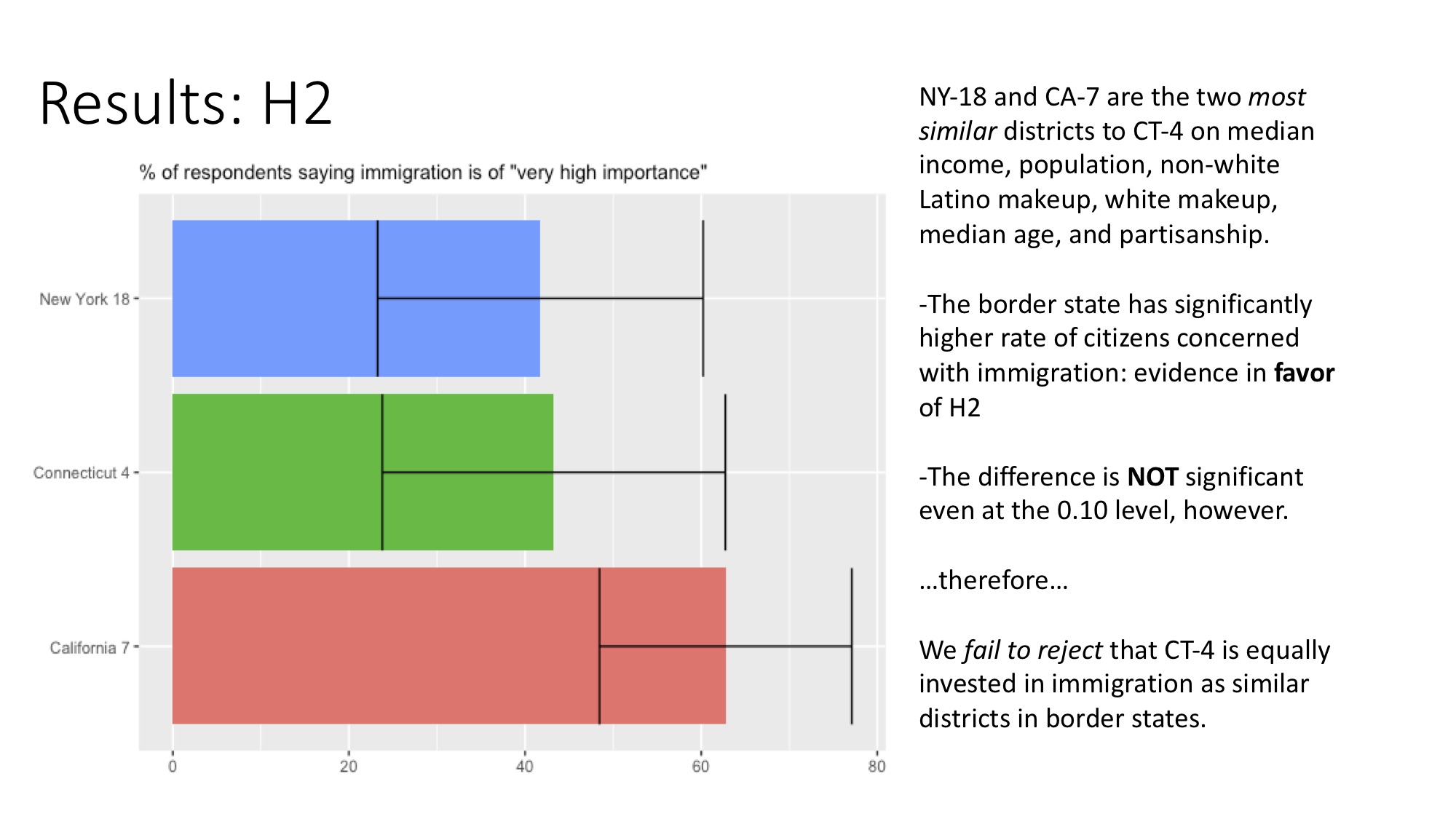

IV. Results: H2

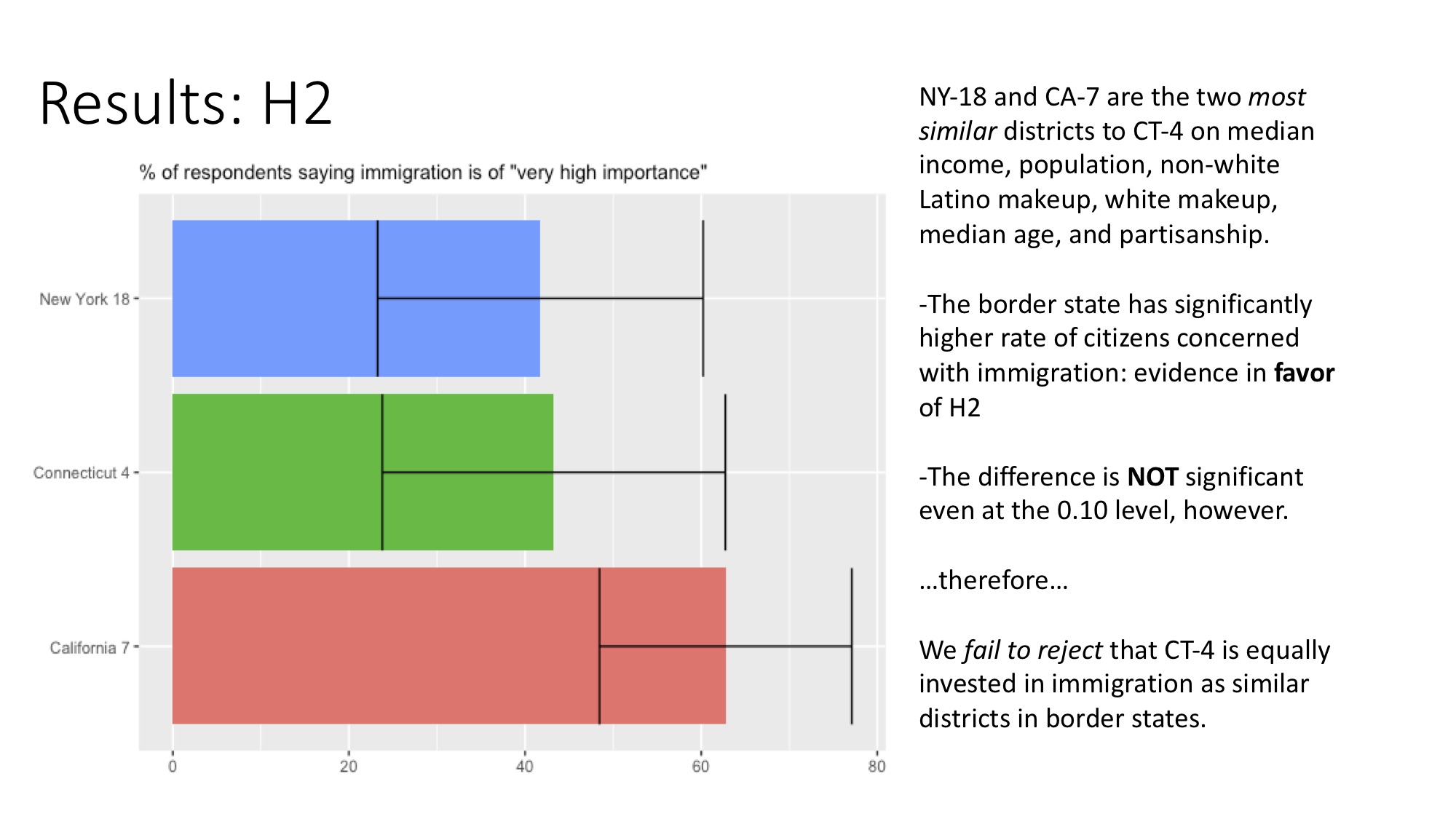

In general, aggregate estimates can mask heterogeneity; that is, an “average treatment effect” is an average and might miss interesting patterns. To know if border-state status causes higher immigration salience for districts like CT-4, or put another way, if CT-4 is less invested in immigration on account purely of its non-border status, I employ a matching scheme. Using the ACS 5-year “Selected characteristics of the native and foreign-born populations,” I identify all districts that are within half a standard deviation of CT-4 on the following variables: median age, median household income, percent non-white Latino, percent white, population, and Democratic vote share (measured from Cook Political Report data). This resulted in two other districts: CA-7 and NY-18, which is right next to CT-4! This “matching design” infers a causal effect of the “treatment” (being on the border vs not) on the outcome (survey respondents’ rating of immigration), on the assumption that we observe all other variables that could conceivably change the outcome. This is surely false, but we get a good estimate. The bar chart shows weighted means (using CCES “pre” weights), with 95% confidence intervals, of the percentage of voters who think immigration is “very important.” While CA-7 voters say so at higher rates than CT-4 voters, the difference is not significant. This difference might be significant if we had more than 99 responses (45 for CA-7, 26 for CT-4, and 28 for NY-18), but it is the data we have. We thus fail to reject the null hypothesis that immigration salience does not vary between medium-sized, liberal, wealthy districts on and off the border.

V. Links

Link to 2008 election data: https://www.fairvote.org/overview-and-data

Link to 2018 election data: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WxDaxD5az6kdOjJncmGph37z0BPNhV1fNAH_g7Ikp C0/edit#gid=0

VI. Works Cited

Craig, Maureen A., and Jennifer A. Richeson. 2018. “Hispanic Population Growth Engenders

Conservative Shift Among Non-Hispanic Racial Minorities.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 9 (4): 383–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617712029.

Dunaway, Johanna, Regina P. Branton, and Marisa A. Abrajano. 2010. “Agenda Setting, Public Opinion, and the Issue of Immigration Reform*.” Social Science Quarterly 91 (2): 359–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00697.x.

Hopkins, Daniel J. 2010. “Politicized Places: Explaining Where and When Immigrants Provoke Local Opposition.” The American Political Science Review 104 (1): 40–60.

Jones, Bradford, and Danielle Joesten Martin. 2017. “Path-to-Citizenship or Deportation? How Elite Cues Shaped Opinion on Immigration in the 2010 U.S. House Elections.” Political Behavior 39 (1): 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9352-x.

IV. Testing the effect of location

IV. Testing the effect of location