SEMINAR 1: We Begin

[This was a test of the new “blackboard” in our room — which is appurtenant to the super high-tech AV module, which was showing drone flyovers of the business districts of global capitals when I came into the room. Just saying… – DGB]

Our launch session for the semester. There was no pre-circulated reading, so this was mostly an opportunity to make some introductions, and also, yes, to sketch the structure of our class — its rhythms, and (expected) trajectory.

And I will take a moment to review some of that here. We aim in this class to achieve a collaborative final project. And we do not stipulate the nature or form of that final project in advance. Rather, it is our hope that, across the semester, a workable collaborative endeavor will emerge — out of our readings and our conversations. I will try to do my part in trying to help shape this process, but it is indeed a process, and we all have to be willing to throw in together and trust the emergent dynamics. It may be hard! But the possibilities are endless, and that itself is something real and beautiful and important. I gave some examples of what has come out of previous versions of the class, and also told some stories about the challenges that can arise in the attempt. More on all that if and as it becomes relevant…

I also sketched the way our seminar meetings will generally work. Namely, that we will gather for the first half of our class each week and discuss pre-circulated readings (which I will provide, at least initially — but that I invite you to play a role in suggesting / recommending / sharing), and then, for the second half of the period, we will usually be joined by a guest (often, though not exclusively, a member of the IHUM executive committee). In that second half of our meeting, conversation will turn around a reading provided in advance by our visitor, who will also send along a sample/taste of their own work (by way of introduction). Each of you, as we discussed, will be responsible for two “write-ups” (a little bit like what I am doing here) over the course of the semester. These will be determined at the end of any given session, basically on a volunteer basis, generally two people per session. Posted to our discussion thread here on the website, these write-ups will both create and reflect the arc of our seminar. Oh, and the two people who did the write-up the previous week will be responsible for a brief oral welcome / introduction / resume / synopsis with which we will welcome and orient our guest the following week.

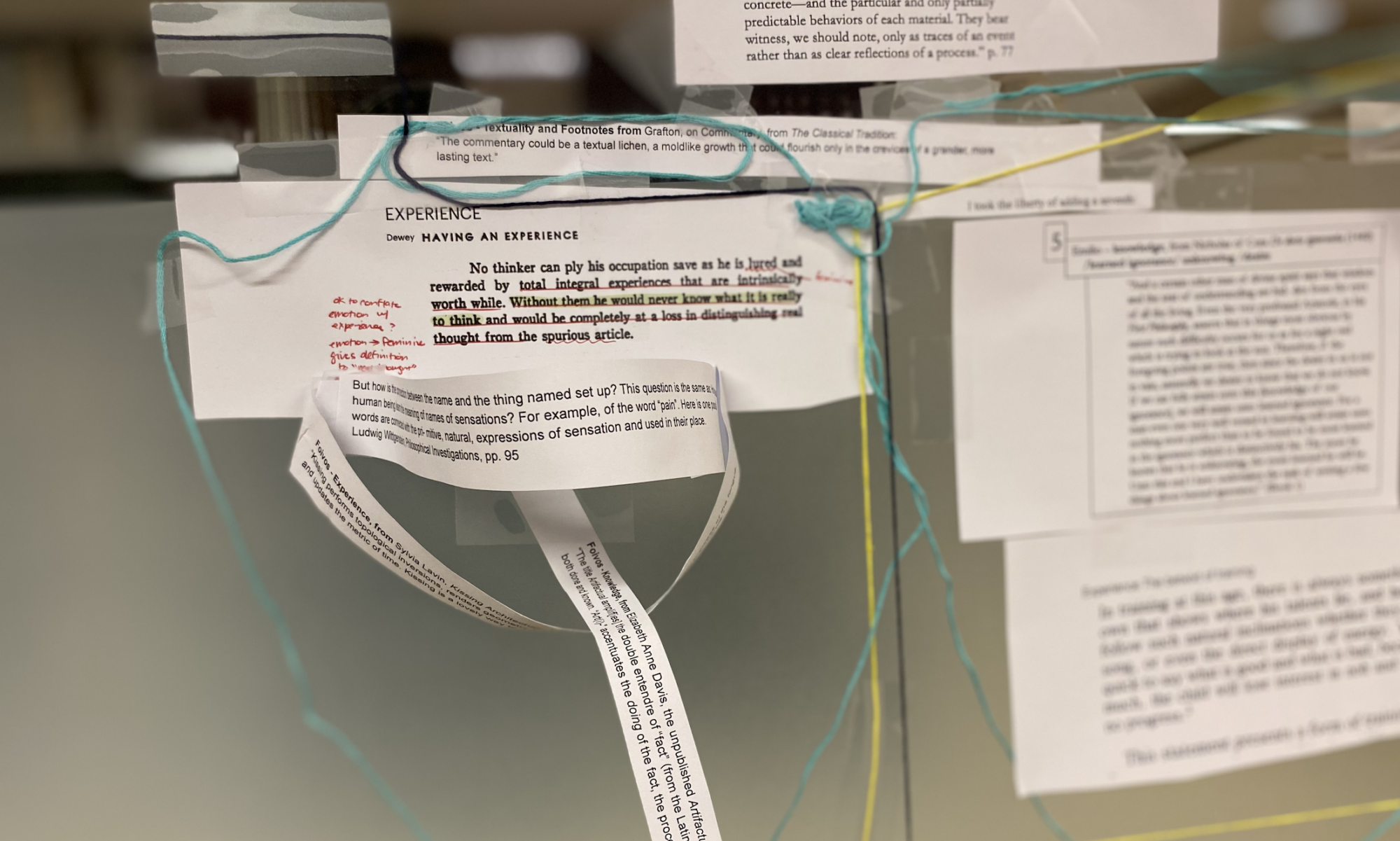

While we did not really have a full-on seminar this week, we did do some seminar-style conversation. Here’s a picture of the board on which I scrawled some notes as we talked.

It is a little difficult to reconstruct how that conversation went, but I remember very well SGM’s wonderful question / observation about that moment over to the right — where I wrote “auto-antonymic,” and offered a reading of the English expression “make believe” as one of those strange linguistic situations that can be understood in two perfectly opposed ways. We can work to “make” person X “believe,” and that means securing their confidence and commitment; at the same time, “make believe” in idiomatic English means “to pretend, to feign.” This is odd. And SGM raised her hand and sort of noted something along the lines of this being the kind of thing we humanities people find interesting, and then she also reached toward a question that was a little hard to put into words. So it is possible I will fail to get it exactly right here. But it was perhaps akin to “I’ve never heard that before — that ‘auto-antonymic’ idea — when will the time come I’ll know all that kind of stuff?”

That isn’t really what she said, exactly. But that is how I understood the question. And phrased that way, I must say, I loved the mood and tenor of the whole thing, in that it seems to me to speak in a very deep way to the project of educating ourselves in the ongoing way that constitutes a committed life in learning. Because the answer, of course, as SGM herself surely knows, is that, well, one never really gets to the point that one knows all the stuff one would like to know — or perhaps even that one “should” know.

That “should,” which is imposed by disciplinary expectations and the dynamics of professionalization, weighs heavily as a kind of miasma of anxiety over much of academic life. But part of what made the question so wonderful is that it is a question about what it’s like to be a scholar, or to aspire to the being of a scholar — and I think that is how the word “being” ended up on the board.

Why is it crossed out? Well, it is crossed out because the conversation took a turn into historical epistemology, and we did a loop through the university as a site for “knowledge” production — recognizing, along the way, that knowledge, as it has come to be defined in our tradition, mostly stands apart from the matter of being. By the working definitions salient in the modern university project, knowledge is strives for an impersonal (indeed, “objective”) character, and this means that knowledge is, strangely, always a little bit without us.

Which makes it awkward for us. Since we are never without ourselves — or anyway, we encounter that form of dissociation (alienation?) relatively infrequently (I hope).

We will surely return to this theme, which is taken up a bit here, in the little book that came out of an earlier version of this seminar (and that we discussed….). Onward!

SEMINAR 2: w/ guest Gavin Steingo

Our first “proper” session — in that we met together as a class for the first hour today, and then we were joined by our guest, Professor Steingo (from the Music Department), from 2:30 to 4:20. Although this session was a little unusual, as we noted, because Gavin came with his entire graduate seminar. And the reason for this? I explained: Gavin, as it happens, had assigned several chunks of my 2012 book The Sounding of the Whale in his musicology seminar, which is themed around “animals and music.” He had invited me to join the seminar to talk about chapter 6 from my book, which deals in detail with the emergence of ideas about cetacean “intelligence” and “musicality” — specifically the “discovery” (or was it an invention?) of “whale song.” But I told him I couldn’t visit his class because I was teaching this class at the same time, although our class runs, I explained, on the jet fuel of interdisciplinary visitors, and would he like to be one?

Thus was birthed the idea of our, in effect, mutually inviting each other as guests, with the effect of combining our classes for the second half of the session today.

I have to say, writing this in the hours immediately following our session, that I thought this “experiment” was genuinely a success. Speaking for myself, I really enjoyed the second part of our gathering, and felt like I learned a lot (and also got to talk a fair bit — maybe more than would be ideal, I recognize!).

But before I get to that, maybe a few words about the way our first hour went.

This felt (was this just me?) frankly a little rushed somehow. We may need to build into the syllabus a session or two just us together, with no guest (I have done this before), just so we are sure to get enough time to ourselves, in order to dig in on our readings and our questions. But we certainly got to some big questions very quickly. There was SM’s opening gambit, which I will translate / relate as follows: “reading this stuff about knowledge and power, and the specific cultural conditions of this or that ‘regime of truth’ just makes me want to ask directly — how far are we willing to push this stuff? I mean, what about gravity, and stuff like that? Is “gravity” some kind of cultural construction? The product of some specific regime of power / knowledge?”

Let me be clear: SM did not use exactly those words. But that was the question as I heard / felt it.

And a crucial question it is. Indeed, one might argue that it is the question of questions. A question that (and we got to this at the end of the seminar, didn’t we?) poses / states a central challenge to the very idea of the humanities as a program. Or anyway, I think the question can be construed to have that force. And that’s because the question can be understood to ask about the limits (if any) of science’s claims concerning “what obtains” (and the “workings” of same). Or, to put it differently, the question can be understood to request clarification as to whether there are any limits to the project of understanding human understanding in human terms — in the terms, that is, of history, society, and language.

I am not going to try to answer / resolve this challenge as posed. We have the rest of the semester to resolve this one, and I am sure we will return to it. Suffice it to say, for now, that this formulation of the question reflects the central preoccupations of my own field (the history and philosophy of science) over much of the last fifty years — though it cannot be said that my “disciplinary” obsession with historical epistemology entitles me (and / or my colleagues) to a privileged claim on the problem.

Other stuff that happened in our first hour? I talked a bit about the dream of an “IHUM fellowship in institutional jesterism.” We talked about “dithering” (both in a technical and in a non-technical sense). We spent some time on my little grapheme of the two “modalities” of interdisciplinarity, as depicted here:

I thought the idea here was relatively clear: one kind of “interdisciplinary encounter” can be thought of as the result of new knowledge being produced out of the intersection of highly specialized experts working in adjacent domains on a common problem / object / situation. We might call this the interdisciplinarity of experts in their expertise. It is depicted above by the circle encompassing the overlapping branch tips of the two trees (labeled “learnéd / erudite”). I suggested there might be another mode of interdisciplinarity as well, one perhaps less easily positioned within university structures. This was the interdisciplinarity that might result not from going out to the ends of the branches of adjacent expertise, but rather that which might be achieved by movement in the opposite direction, down the trunk and into the roots and “Earth.” This, I suggest, we might call the “interdisciplinarity of foundations” or maybe something like “primordial interdisciplinarity.”

At this point we took an all-too-brief turn into what became a little discussion about intellectual resistance and metaphor and, perhaps, whether any of this amounted to anything at all. I am referring to the turn we took when HG, seemingly a bit puzzled (or anyway, not perfectly satisfied), expressed some misgivings as to exactly what kinds of claims were here being advanced. Metaphors? What was the status of these propositions? Lots of figural language, perhaps. But the referent? Were we sure what it was?

This was a pleasing suspension of the flow, and it occasioned a moment of meditation (by me — but was it an evasion?) on different intellectual “styles” or sensibilities. I admitted that I have, at different times, thought of myself as a “serial understander” — by which I mean that I have a somewhat itchy trigger finger on my “I understand this!” sidearm. Do I actually “understand” what I continuously persuade myself I have already understood? Maybe not. But I am so addicted to the pleasurable feeling of “understanding” (or “the pleasurable feeling of believing myself to be understanding”) that some labile quality of my inner life continuously persuades myself that I have “understood.”

By contrast, I have several friends (dear friends, brilliant friends!) who seem positively never to permit themselves this satisfaction. I happily concede that several of them are very definitely much, much “smarter” than I am, much “quicker” in their technical command of difficult topics — but for all that, they always seem thoroughly dissatisfied with whatever it is that is trying to work its way into their heads: they resist, they push, they probe, continuously finding ways to be not yet “with” the claims as they stand.

This, too, can be a form of love — love of the ideas, love of the thinking. I am not very good at it.

And our guests arrived.

I won’t try to summarize this part of what happened. Lots of interesting things, I thought. We talked a bit about musicology as a discipline. About the notable fact that it is possible to be tenured in Music (on the “composition” side) without a monographic book. About the absence of tenured faculty on the pure performance side. About what it means to figure music composition as a “research” domain, in which something like “advances” are made in a “knowledge producing” project.

And we rounded (across a fair bit of actual discussion of animal communication, cetacean “phonation,” and the idea of music as the “other” of reason) to a challenge with which we will surely spend more time: Is it possible, now, within the university “humanities” and/or “qualitative social sciences” to be anything OTHER than a “scientist”?

CB’s writeup on the session follows; “Huut” is below that.

-DGB

* * *

[CB starts here:]

Our class on 9/13 was the first to have a guest, an ethnomusicologist, for the second portion. Students in his Animal Music and Communication class also joined. Before they joined, our class discussed the readings on knowledge and (inter)disciplinarity.

We started off with a big question: when (if ever) can we take knowledge for granted? The question was on the table, and although we didn’t answer it then, it would continue as a theme throughout the class. One particular moment between the profs stood out as exemplary. I will outline a simplified version of the conversation with the hope that I understood it correctly. One argued that whale song, although only discovered by humans in the 1960s, existed before then, and was not contingent upon human discovery. The other argued that song is a cultural imaginary–it exists only because humans place value on the idea of music in culture–and therefore it was not a phenomenon that was discovered in whales, but one that was constructed based on human aesthetic values. Here, knowledge is in question: do we know whales have song, or is whale song a cultural construction?

The conflict between taking knowledge for granted or questioning it brings me to another recurring theme form class, that of “going back to basics.” We discussed the idea of a class “jester,” who would enter an advanced class and ask basic questions. There are disadvantages to this idea; of course, the point of an advanced class is to move beyond the basics, and this character could easily waste time. But we focused on the possible advantages, two of which stick out to me. One advantage is that the “jester” might help clarify concepts for those in the class who do not have the same foundational knowledge, and who might be unwilling or unable to articulate that in class. Another advantage is that it can bring the knowledge that advanced students/professors take for granted into question. It creates an avenue (for those willing) to reevaluate what they hold as truth, and it can produce interesting conversations and moments of disagreement, like the conversation between the professors on whale song.

Several other interesting themes came up, including the idea that fear drives much knowledge production and is a contributing factor in the upholding of disciplines. We see it in many aspects of life including academics and even conversations on gender: when categories begin to break down, many respond with negativity and fear. On the flip side of that, we discussed what can happen when one easily moves about, exploring a wide range of ideas. The concept of “dithering” provided a useful metaphor, and suggested that when we remove the fear of categorization breakdown, we may gain new insights.

I have not exhausted all the themes from the conversation, but I will end with an idea our prof brought and guest professor expanded on. They discussed the importance of the moment that reason and rationality break down, and how this moment is a fruitful space for their research. The guest stated that he is in the discipline of (ethno)musicology broadly because of his observation that when reason is exhausted, many turn to aesthetics–in particular music. He noted Kant’s three critiques as a perfect example of this move (the first two as critiques of reason, and the third as a turn to aesthetics). I am similarly drawn to studying music because of its unique position between the rational and someplace beyond.

And I found a parallel between the guest prof’s comments and our prof’s study of what would become the save the whales campaign to be especially interesting. We learned that the public became interested in saving the whales only after it was discovered (or scientists perceived to discover) that whales sing. The earlier scientific arguments in anti-whaling movement (arguments about whales’ reproductive patterns, which at the very least shed light on the fact that whales are living, growing creatures, and in that way are like humans) did not reach the public. In other words, arguments about reason–that whales live, and if humans kill fewer, they will still have enough of their resources–were not enough to convince the public. Only after the aesthetic turn–that whales have a culture of singing–were the public convinced. The aesthetic turn had a profound practical effect on public attitudes and policy. This moment highlighted the close proximity of two or three disciplines–history, science, music–and revealed the almost inevitable nature of interdisciplinarity.

-CB

* * *

[“Huut” (a pseudonym) starts here:]

Bonjour !

At first I thought that would be Princeton. We would all be someone else’s Belle. From one familiar face to the next with a couple books in our hands. Bonjour ! Bonjour ! Bonjour ! Bonjour !

My apologies, I will start again.

Hello.

I ended up being quite uncomfortable.

Say Hello!

That’s not it. Nobody cares. Let’s start again.

How can someone make “Hello” sing?

I was told that everybody is smart but few people are kind.

I sing my hello like a whale. You spend your life looking for a comfortable position for your tongue in your mouth, but can you imagine it, when your tongue is as big as an elephant?

Sorry, I’ll start again. (Hello!)

Do you know this whale I’m talking about?

But you do know it.

First there are all the other whales. For thousands of years they were the loudest animals on the planet, before the men and women who can’t hear them. Whales with accents, personalities, cultures. Whales supporting each other and taking turns to assume roles, like nursing, while the others hunt in deep waters their offspring can’t reach. They can’t reach them. They just can’t reach them, at least for now.

But there is this whale that sings 27 Hertz higher than all the others. The Americans found it by accident and they called it 52 Hertz. “They do not know and cannot guess its species”, writes Hal Whitehead. “It could be a hybrid. It seems to be an individual who has not picked up either a culture of song or a culture of migration, and its track was unrelated to the movements or presence of any of the other whales. It had its own songs, its own movement patterns, but they are not culture, and without culture it was alone.”

In an increasingly noisy ocean, there is a whale that sings in its own way, in its own tracks, and for which we, who do not know how to listen to whales, have nevertheless paid attention only for an instant.

Hello — This whale is me.

-Huut

SEMINAR 3: w/ guest Jeff Dolven

We jumped right in today (with a well-worn [and SILENT] horseshoe on the table), thinking about the category of “experience” and its status in relation to “knowledge” and “knowledge production.” After a turn through the Benjamin, and that powerful idea that experience itself (or, anyway, “communicable experience”) was literally blown apart in the trenches of the First World War, we moved to reflection on Agamben’s citation of the same passage (for Agamben it is the pre-linguistic, “infancy,” that sets the aspirational horizon of something like pure experience). Before long we were reviewing Dewey’s careful distinction between experience-as-such (the pervasive condition of the live animal) and the distinctly human notion of “an experience.” We worked this passage for some time:

And particularly on that telling sentence in the heart of things: “No thinker can ply his [sic] occupation save as he is lured and rewarded by total integral experiences that are intrinsically worth while.”

Is this correct? Or is this a mystification? Who is a “thinker” anyway?

We sat for a while with Dewey’s intuition that “an experience” amounts to a certain integrity of cognition and affect (“intellectual” and “emotional”), and that “an experience” possesses a coherence (a wholeness, achieved through narrative? through all-at-once-ness?) that stands in some significant relation to conscious being itself. Dewey is said to have read Heidegger and more or less to have remarked “yeah, that’s what I have been saying.” And so we might say that Dewey sees in “an experience” an index (or is it a sacrament?) of “Being.” This is, I think, a “humanism.” It might be wrong. But it is certainly a claim.

And to that claim we read Joan Scott as saying something very much like “NO”!

For in her account, invocations of “experience” are always to be held suspect — in that they all too easily function to “black box” dynamics of history (and power) that must be held up to scrutiny. She is wary of the way the implicit irreducibility of “the experiential” thwarts (or evades) criticality, and thereby too easily functions to buttress various illegitimate privelegings of perspective — of which the normative “human” of the “humanities” must be called out early and often.

We did not resolve this faceoff. But we brought it into the room. And it gave rise to a quick loop (shown on the board) into the very idea of a “critical theory” — an account of what obtains that is thought to have a self-executing emancipatory effect. See the lower lefthand corner, where the names “Marx” and “Freud” appear. (And for a polemical treatment of this idea, consider Raymond Guess’s contentious The Idea of a Critical Theory.)

And genealogy? Yes, we did some of that too. In that we took some time to discuss the process (of particular interest to Gadamer) by which “experience” came to be entailed to service in the project of knowledge production — via the rise of the “experimental philosophy,” by which certain kinds of experience, under certain circumstances, could be understood to do certifiable epistemic labor.

But then the knock on the door, and Jeff Dolven was with us.

Conversation turned to SCALE, via the Horton, and our exercises, which he and I have preserved here in this set of slides.

Before long, I was good and confused about some pretty fundamental things (what, if anything, is the actual distinction between a “difference of kind” and a “difference of degree”?), and we were musing on Cantor’s diagonal argument. Scalar alterity? Indeed.

But Horton’s critique of trans-scalar humanism? I dunno. Isn’t “trans-scalar humanism” what is otherwise known as REASON?

*

RC and HK offer their own thoughts on the session below!

-DGB

* * *

[RC starts here:]

I looked forward to this week’s seminar after last week’s rather lively discussion with Gavin, and it did not disappoint. It felt helpful to spend some extra time to rooting ourselves in the readings, as they covered quite a bit of ground this week—much of it unfamiliar to me. (Thank you, HK—for graciously agreeing to take on the second half’s discussion on scalar alterity, which I’m still trying to make sense of!)

We began our discussion by reflecting on dialogic criticism—that is, criticism that is “conversant with the author.” This is the critical mode of Dolven and Kotin’s The Parkland Mysteries, and seems to be increasing in popularity. I could not help, of course, but think of Roland Barthes’s 1967 essay, “Death of the Author,” which argues that we should dispense with traditional literary criticism’s fixation on the intentions and biographical context of the author in order to understand the meaning of that author’s work. I wouldn’t say Dolven and Kotin’s style of criticism is traditional, exactly, but it does seem closer to the ways we tried to make meanings of things, of texts, in the past. With the author hovering just at one’s shoulder, figuratively and/or literally. (Specifically thinking pre-twentieth century.) At the same time, this mode of criticism also feels decidedly modern to me. I was musing about why it might be regaining its popularity and wondered if the dominance of social media had anything to do with it—how the line between public and private has been all but eroded, how artists, intellectuals, celebrities have increasingly lost their mystique. (For better and for worse.)

We spoke too about the nature and structure of universities: of the disciplines as “scalar formations”; of knowledge production as a self-defining enterprise; how even non-scientific disciplines have taken on scientific architecture; and how the idea of experience might figure into all of this. DGB mentioned that “experience carries water for knowledge production,” a metaphor I rather like and am still pondering. And we talked again about the course’s aspirations—to imagine other architectures, for example.

I found our discussion of critical theory’s endeavors especially luminous: the dream that by understanding what is, we might arrive at what ought to be. This is such a helpful framing—one I wish I’d had my first year of grad school. David Hume contends that we cannot get from is to ought (Hume’s fork), while Hayden White tries to resolve the is-ought problem with historicism. [DGB: this is the claim of the first chapter of Hayden White’s magisterial and exigent Metahistory (1973)]

By way of attempting to set up something of a transition for HK, I’ll end with a quote from Dolven and Kotin’s The Parkland Mysteries: “Pastoral is always about what you knew and when you knew it, an innocent space hung with fatal apples.” This quote took the breath from me—its image and timbre. I scrawled it at the top of Walter Benjamin’s essay on experience and poverty. Many things here: I am first struck by how we keep returning to trees. It seems hard to talk about knowledge without the trees. Perhaps we should go out to the field. I’m struck too by—even though I only jotted Dolven’s quote on Benjamin’s essay because my notebook wasn’t handy—Benjamin seems to similarly inhabit the elegiac: “Where has it all gone? Who still meets people who really know how to tell a story?” It made me curious about the possibilities of this backwards glance, of the elegiac as a launchpad for meaningful criticism (rather than reactionary nostalgia for a mostly mythic past, with which we might be more familiar. . . ). Perhaps what we once knew, and how we thought we knew it, can be just as informative as what we don’t know now, and why we know we don’t know it.

-RC

* * *

[HK starts here:]

Professor Jeff Dolven joined our conversation. Before his arrival, we read various takes on “experience.” How to think experience diversifies one’s disciplinary training and intellectual aims. In the latter half of the seminar, we focused on Zachary Horton’s The Cosmic Zoom. A fun reading exercise followed. We tried to understand and experience Horton’s key concept, scalar alterity.

The Cosmic Zoom allows you to mull over multiple ways to experience interdisciplinarity. According to the University of Chicago Press’s website (https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo63099371.html#anchor-reviews), The Cosmic Zoom belongs to these categories: History of Ideas, General Criticisms, Critical Theory, Media Studies, Philosophy of Society. Horton himself is a media, literary, and game studies scholar and Jeff’s expertise is early modern English literature. All these crossovers of different scholarships centered on The Comsic Zoom, offering the heuristics to think something differently. I meant “things” as thoughts, ideas, and practices derived from clashes and encounters from disciplinary practices. In other words, interdisciplinarity of scalar alterity is a promiscuous (!) dithering, concept that we talked about in our previous class.

We then discussed how to read a photo that Jeff brought, the musical scale. Musical scale exemplifies that scalar alterity is the contact of two things. Musical scale is a spatial phenomenon, notating hearing to a flat paper. At the same time, as FH pointed out, musical scale is a temporal encounter, transforming time into a graphic medium. Speed, rhythm, and our bodies react to the gradation happening on this paper. The practice gives the virtual scene from the tangible image. We zoom in to the scale and then zoom out to see the human scale. Experience of scale is also far from neutral and objective. Some scales hold more importance than others, as CB mentioned, implying the political dimension from scalar access.

We then experimented with how we could alter reading practice. Mediation, one of the key practices, can define our exercise. Each participant brought photos they took to see four taxonomies of scalar alterity. The first category of scale is a map. CG’s photo exemplifies the category. In CG’s photo, we see someone’s vision. The eyes of the photo watched their MacBook’s screen while grasping the broader view from the backdrop of Princeton Chapel. On the laptop screen, we see the satellite image from Google Maps. A bird-eyed view of the map draws the geometric division and multiple grids representing the lands and architecture of France. An interesting contrast between geometrical graphics and a green background was found. While HK mentioned the machinic visions’ inhumanness, the pastoral green successfully melded into the Princeton lawn’s green, showing the scale altered. It was the example of scalar access, where the scalar alterity happens. Houses, green fields in satellite images, shadows on the monitor, and the indexical image of someone’s viewpoint sitting on Princeton’s lawn depicted scale as a map and the experience of mapping.

We moved on to FH’s photo. There was a small flower pot with a blurred background with multiple trees. The photo evokes the discussion: what is the difference between size and scale? Furthermore, what is the difference between alterity and difference? Size involves differences, such as different sizes of small pots and large trees. Scale involves change and shift entailed by a certain encounter and the possible way of thinking “alternative,” if this is the right description. Scale is, thus, fundamentally political. Transitions and modulations happen to adjust and change what we think and practice. We briefly talked about Hannah Arendt’s quote, which is a powerful reminder of the politics and ethics of scale; the catastrophe arrives when humans fail to realize different types of scale.

We also discussed the anti-humanistic tone alluded to in scalar alterity. DGB asked; does scalar alterity minimize humanism? The technical metaphor of zooming in and out pertained to his point. Moreover, how can we not obsess with the fantasy of holistic experience implied by scalar alterity? Horton’s scalar paradox, another key concept, responded to these points. Scalar alterity is paradoxical because the scale is both heuristic and ontological. Navigating humanistic methods and extension of perception brought questions about methods in disciplines. History’s long duree to literature’s close reading can be encountered, blended in one discipline’s interdisciplinary experiment. We access books, the material medium, with all scalar alterity, different disciplinary inquiries, objects, genealogies, and bibliographies. All to say, we are experiencing scalar alterity with multiple dithering from scholars.

One instance of scalar alterity that I could think about is a footnote. Footnote is a method and a feminist practice. Katherine McKittrick’s Dear Science and Other Stories might be the perfect example. In the book’s footnote, black anticolonial thoughts, cultural geography, Black history, poetics, and Detroit electronic music open up all different scales of thoughts and practices. Sometimes, the footnote takes more than half of a page, making the conventional reading a bit challenging to practice. Footnote becomes an extensive map interweaving voices outside the canonical methods and disciplinary divisions. It configures ethics and politics of experience as well. In Dear Science and Other Stories, one visible paper visually maps Black intellectual genealogy. I am curious how other colleagues experienced scalar alterity.

-HK

SEMINAR 4: w/ guest Christy Wampole

Our opening conversation circled the AAUP statement defending universities, a document generated on the 2019 / 2020 watershed, a moment we can fondly remember as pre-pandemic, but that we took some time to reconstruct as a particularly fraught episode (politically speaking) for colleges and universities. We took a little time to sift out just who exactly the AAUP is, and to reflect on the specific fears engendered by several Trump-era initiatives that were interpreted within the liberal establishment as “shots across the bow” of the good ship American Higher Education.

But the truth is, the energy in the room was decidedly unsympathetic. Which is to say, while everyone seemed to appreciate that the authors of the statement were trying to mount a forceful defense of universities, academic labor, and the values of universitarian inquiry, really no one in our seminar seemed willing to step forward and champion the line of argument manifest in the piece. On the contrary, HG went right for the strong-arming grammar and barely sublated “violence” of the opening sentences — and finally found the piece an uncomfortable litany of (effectively phony) hyperboles which felt basically indefensible, even if they were occasioned by other (effectively phony) hyperboles. The repeated invocations of “expertise” raised hackles, and seemed not to align with the sensibility of the room. Further, the emphasis on the “hard work” involved in disciplinary knowledge production struck some of us as almost a little silly as “protesting too much,” as a kind of dour intoning of the Protestant work ethic (see the board above) — as if, somehow, it was the sweat of our brow in our air-conditioned offices that entitled us to respect on the floor of the House of Representatives)

I confess to having maybe been a little surprised by how little quarter the piece was given. CG actually even got everyone out-loud giggling about the part where the authors sturdily invoke the Enlightenment dream (but was it ever only the Enlightenment dream?) of a knowledge transcending the political.

Fair enough, I guess. Although I would like to remind everyone that there is quite a lot of knowledge that is a lot less manifestly “political” than a lot of other knowledge (no? or anyway a lot harder to demonstrate to be “political,” and isn’t that the point?) — and if you genuinely have no feel for there being something special about the kinds of knowledge that get farthest from the “merely” political, you are either a very very special kind of radical thinker, or you have perhaps not thought hard enough about this stuff.

Or anyway, so suggest I.

And then there was the Butler. We did not spend as much time as we might have done on Butler’s response to the AAUP statement, but I tried to suggest that her mode of “criticality” looked a lot like the ambition to use “critical” humanistic / textual / interpretive modes to correct the errors made by those who pursued knowledge without adequate command of the relevant resources. But this, I suggested, looks a lot like a “science of science” — which can hardly be said to have abandoned faith in a knowledge project systematically stripped of (at least undesirable) ideological contamination.

Did you feel the force of this argument? Or do you feel I have her position wrong?

I do not mean to suggest that Butler cannot defend herself from this line of scrutiny, but I do tend to read pieces like this through the lens of Bruno Latour’s late work (e.g., “Why has critique run out of steam?” and “Towards an anthropology of the iconoclastic gesture”), which tends to see the critical ambition of “science of science” as a project that collapses exactly with the rise of constructivist STS and strong-program anthropological SSK (sociology of scientific knowledge). More on all that anytime for anyone who is interested — although this starts to feel “disciplinary” from my sector.

We left all this with me once again (perhaps nebulously) gesturing at the category of experience, as well as that of making, projects that I again suggested seemed to operate perpendicularly with respect to the plane in which the “science of science” problem arises — the board catches some of all that (quite schematically!) here below.

And that was that. We then took half an hour to dig in a bit on the final project. In this we were assisted by a gracious visit from Lauren Dreier, a student in last year’s class. She brought along some samples of the final project that came out of that session (the cards documenting our participatory annotation / citation collage experiment, a still shot of which is actually the header on our course website this year, fwiw). Her visit provided the occasion for me to circulate some of the Keyword books (a final project from an earlier year), and also to sketch some of the contours / norms by which the more successful of these enterprises have operated. I’m going to repeat those here so that you have them for consideration. The most successful final projects tend to have something like the following characteristics:

1 – A somewhat “modular” structure, such that there is a discrete “deliverable” of some reasonable size/scope that everyone does in some broadly “individual” way (this is necessary, such that I have a way of responsibly evaluating everyone on a separate and equitable basis; a component of my administrative/institutional obligations as I understand them);

2 – A larger integrative enterprise that lets the whole of these together be, somehow, greater than the sum of the parts (as we say in idiomatic English);

I also added that, vis a vis the issue of “creativity” or “form” or “limits,” I tend to use the following pragmatic analysis: I would want to feel like I could “defend” our final project (1) as a final project (2) by a group of graduate students (3) in this graduate seminar… if asked by a group of my professional colleagues to do so.

Also, I noted that we will try to keep as much of the group together in one project as possible, but that it is not impossible that two or even more group projects might ultimately emerge. Finally, is a “total fail” possible? Yes. And if we get there, we will deal with that — but the “last resort” is everyone writing a 25-30 page paper (just like in a more “regular” graduate seminar).

Make sense?

Nobody needs to be exactly focused on the final project in any formal way at this point, but everyone should be keeping ideas and possibilities in mind — and you are invited to discuss them among yourselves, or to surface them in class as you like. Examples of interesting things done by groups of people (even if they are quite different in terms of subject from anything with which we are concerned) can be quite useful / inspiring (I have requested, on the assignments page, that you give that some thought for this week).

I won’t say too much about Christy Wampole’s visit, leaving that largely to JN and CG and their write-ups below. However, I do think it was a very interesting conversation. I found the film itself basically unwatchable, unfortunately. Not because I am squeamish about skin diseases (I am not), but rather because I am a highly suggestible and somewhat neurotic/compulsive-spectrum person (unsurprisingly), and I therefore find big long deep dives into the intimate conditions of anguish/paranoia/craziness more or less unbearable. I just did not have it to give on this one. That is not to say, however, that I failed to do the homework. I “watched” the film — but as Christy Wampole herself noted, there are many ways to watch a film, and I watched it in such a way as to prevent most of it from getting inside me in any meaningful way. Sigh. Oh well.

As far as the conversation went, I very much appreciated the turn into the weird borderlands of the fictive and the documentary, and I mentioned this important article from 2009 by Carrie Lambert-Beatty (which is now on our reading list for next week — oh, and I referenced this related work of mine, which is about this).

The stigmata stuff was cool too. I am always interested in situations where cognitive or affective aspiration bends the body and/or transforms matter. It is possible to believe that all knowledge aspiration is ultimately an aspiration for consilience/unity/metempsychosis. I am not saying I quite believe that, but stuff along those lines veritably haunts epistemology.

In closing, I want to underscore that moment at the end, where Professor Wampole invoked “wider publics” in connection with her discussion of the essay as a form. I flinched, basically because I think those two things want to be kept separate. One can be for or against “public humanities,” for or against scholars attempting to reach non-scholarly audiences (I am “for,” basically — what’s not to like? except scholars thinking in terms of “trickle-down” intellectuality, which is actually fatal, in my view, to most of what is good in the work of thought), but the essay strikes me as a form whose importance lies precisely in its distinctive orientation to the conjunction of knowledge and experience, of knowing and “being.” And it is my belief that we could do with a GREAT DEAL MORE close attention to precisely that conjunction…entirely within university precincts. So for that reason, I am especially jumpy to the essay being relegated to (even “characterized as”) an instrument by which “technical” scholarship can be made more “accessible.” It certainly can function that way, but I take that to be a relatively “low” and even not-that-interesting manifestation of “essayism.” Whereas what the essay has to teach us about what is missing from disciplinary knowledge production strikes me as IMMENSELY IMPORTANT — indeed, profound.

But more on that as we continued to make our way across the term! With thanks to all, and especially to Professor Wampole!

-DGB

[JN below, and CG follows]

HG gave us something to talk about this week, offering a nondescript white-and-blue appliance that fits into a wall outlet. After fielding a few guesses, he revealed that the device claims to emit an ultrasound frequency that is inaudible to humans and our medium-sized mammalian companions but nasty to smaller pests. It draws a circle around the admissible creatures in a civilized home. At the same time, it might be a conjuring trick, a snake oil diffuser. Because the sign of its function is given in another sensory domain altogether, a blue light, one cannot be altogether sure that any noise is being produced at all.

We turned from this object to an undeniably noisy piece by the American Association of University Professors, published January 2020 at a hinge point between pre-Covid and mid-Covid Trump. HG broke the seal on pointing out the piece’s bombastic, even flamboyant rhetoric, pointing us to anaphora and possible hyperbole in paragraph four. CB contributed that while the constructed opponents in that paragraph might seem exaggerated, recent political developments in the United States mean that the fears evinced in the piece are far from unreasonable.

We seemed more or less in agreement that the authors of the statement bought into a more sanguine positivism than any of us arch humanists would willingly cop to. We tried to get to the bottom of who exactly the statement was speaking for and why it adopted this tone. Graham asked us to consider the AAUP’s peculiar position: a not-exactly-“union” of university professors across a wide range of post-secondary institutions, an industry trade group with a stake in maintaining the cultural cachet of a graduate degree.

We discussed the position of criticality within the professoriate’s self-conception and, in particular, the position of a humanistic critique vis-a-vis the hard sciences. Graham underscored the presumed superiority of STS and HoS, for instance, in telling scientists what they don’t know about their own practices. SA, a new colleague, described how her more critical artistic practice at times seems to stand at cross purposes with the orthodox neuroscience she does professionally. I suggested the self-importance of the AAUP statement might also be understood by triangulating with critique, as it were, from below, giving the example of ACT UP.

We were then joined by Lauren Dreier, a student in last year’s HUM 583 and an Architecture PhD student with research in soft matter physics and an art/design practice. She came to describe how her group arrived at the annotation game that formed the culminating project last year. This project continues, as evidenced by a test set of tinted cards that we got to handle (lots of tactile engagement this week) as Lauren and Graham talked. A few takeaways for me: Don’t worry that we haven’t settled on an idea yet. Someone will probably have to take the lead. Think about both individual and collective production. Borrow liberally from your workplace.

In the second half of class, we were joined by Christy Wampole’s undergraduate seminar on “essayism.” I was happy to see an undergrad friend, and they were happy to be able to speak English for the first time this semester. Professor Wampole had given us two essays to consider and also brought in two pass-around objects: a precious copy of the Montaigne/Dali volume that was the focus of her essay and the Agee/Evans Let Us Now Praise Famous Men that is referenced therein.

Our discussion dwelled primarily on the video essay Wampole had sent to us. By way of introduction, she set out some of the parameters of the essay as it was being theorized in her class. The essay is, paradigmatically, a Napoleonic form: short, with outsized aspirations. It turns the metaphorical (Montaigne) or literal (Galibert-Lainé) camera back onto the author, mining their psychology and, in many cases, physiology as source material for investigating more expansive questions.

A few topics which concerned us in the discussion of the Galibert-Lainé: parafiction, the unheimlich, and simulated vérité; mise-en-abyme, the unwatchable, and ghost cursors; stigmata and Kaposi sarcoma; what to put in the tenure file…

-JN

[CG follows below]

I really enjoyed reading Prof. Wampole’s article “Dalí’s Montaigne: Essay Hybrids and Surrealist Practice” and was looking forward to her intervention in our class. I found this session particularly interdisciplinary (even if I’m aware we are still questioning this concept) since it tackled the essay genre, applied to painting, as well as photography and cinema (unless it is painting, cinema, and photography that apply to the essay?)

After introducing ourselves, RC and HK presented what we are trying to do / define / question / interrogate in our class. HK referred to the “scalar alterity” concept we discussed with Prof. Dolven last week. On this point, Prof. Wampole stated that this concept could also apply to the essay, especially when it intertwines with other forms of art. She further introduced her undergrad seminar, explaining how it lies at the intersection of a theory class and a creative writing workshop (and, on a side note, I wonder to what extent this definition could also apply to our own class. After all, isn’t this discussion thread – to quote Prof. Wampole – a sort of “cahier créatif” [“creative notebook]? Will our final project also take the form of a ‘creation’? Since we discuss knowledge production, what difference do we make between ‘production’ and ‘creation’? But back to Wednesday’s session…)

Even though we mentioned Prof. Wampole’s article, we mainly spent the second half discussing Chloé Galibert-Laîné’s essai vidéographique (videographic essay) called Watching The Pain of Others. We agreed that defining Galibert-Laîné’s project was not an easy task, and I must admit I still struggle to explain it while typing this… To put it (somewhat) simply, Galibert-Laîné films herself watching and working on Penny Lane’s film The Pain of Others, which is about three middle-aged women suffering from the Morgellons disease and sharing their experience on their YouTube channels.

Many interesting points came up in our discussion with Prof. Wampole and her students, but one that particularly caught my attention was the relationship between knowledge and experience. To what extent does what we know influence our understanding of the world? I believe it was Prof. Wampole who brought up the following question: Is Morgellons a contagion of the mind?

Wednesday, after class, when I was collecting my notes and trying to organize them, I typed “Morgellons disease” on Google and found a definition that I thought echoed our conversation: “Morgellons disease is a condition characterized by a belief that parasites or fibers are emerging from the skin.” (my emphasis) And that’s a point several persons raised during the discussion: the role of belief in experience. How can we persuade ourselves of something? How can the mind contaminate the body and vice versa?

On this topic, Graham mentioned an essay by Carrie Lambert-Beatty: “Make Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility.” It seemed to me that it indirectly echoed Galibert-Laîné’s words in her essay when she wonders if Morgellons disease can be defined as an “excès d’empathie” (excess of empathy). What struck me here is how the form itself becomes empathetic as well. Prof. Wampole stated that the essay is, by definition, an “empathy form” since it confronts the subject to other subjectivities.

Lastly, we discussed how Morgellons echoes the stigmata image. I think it was JN who explained that, in the Christian tradition, the stigmata become a persuasion tool, with Christ showing his wounds after his crucifixion to prove his resurrection. Is The Pain of Others rooted in this tradition? Can empathy become physical?

To conclude, I would like to end with a more personal impression. I feel like our seminar intertwines more and more the question of knowledge, science and fiction (i.e., fictions we tell ourselves, fictions we create from ourselves to produce knowledge), and I’m really curious to see what form this will take in the upcoming weeks and for our final project.

-CG

SEMINAR 5: w/ guest Lisa Davis

We opened today with a brief review of this discussion thread itself, and with some reflections on the way that it wants to serve both as documentation of our semester, as well as contributing to a “centripetal” dynamic. Or at least that is the idea — that by taking some time to read through these weekly postings, we can (ideally!) slightly “thicken” our collective feel for the different perspectives in the room, and perhaps get a little help along the path to some constellation of our group. And we are hoping for some of that coming-together exactly because of our challenge — to try to achieve some form of collaborative final project.

And we spent some time reviewing the general contours of that undertaking. HG showed us (in connection with his expressed preference for less linear forms of notetaking) the tool he uses for composing and graphically representing the stuff he writes down both when doing readings and in class: Obsidian This led to some reflections on note taking as a possible theme for a final project (it is a practice of wide applicability across disciplines and across a variety of stages and phases of academic life). In this context, SA shared some of her own note taking works, which combined graphical and textual elements in explicitly “designed” ways. Stuff for us to think about.

We took a loop into the Carrie Lambert-Beatty article, and even reflected on some ways that the final project might include some “parafictional” elements (I showed this project done by some of my undergraduates during the pandemic), although there were also very legitimate concerns/questions about the status of these techniques, which CG noted appear to be pretty directly at odds with the larger project of truth seeking. If we did go this route, we would need to be careful to consider/control the “critical” orientation of whatever we do. As I expressed in class, I am interested in this kind of thing, but that makes me especially concerned to be careful, and to make sure whatever takes shape is something that you all actually want to do! If momentum builds in this direction, I will ride along but I do not in any way want to push us into this idiom. (I did this essay, “In Lies Begin Responsibilities,” a number of years ago this kind of work, and you are welcome to check it out if you are curious — but no obligation!)

How did we get to that idea of “negative capability” that we had up on the board?

I cannot reconstruct our path. But I do remember that we experimented with the idea that disciplines might perhaps be understood as systems for eliminating or at least managing, this special form of not-already-knowing. One might even suggest that a discipline is constituted by the systematic conversion of negative capability into the distinctively determinate form of not-yet-knowing known as a “research program.”

It was in fact this meditation on different projects of “unknowing” (I will indeed slot in the “Agnotology” reading for next week…) that gave rise to a quite concrete and, I thought, really interesting, direction for a final project: what if we collectively conjured a university “department of negative capability,” and did so by developing a body of (fictive/parafictional) materials along these lines? These might include a departmental brochure, course listings, perhaps some syllabi, maybe even a website. Could be a playful and simultaneous serious way of thinking about the limits of the disciplinary, knowledge-producing paradigm of the modern university. Let’s see if this thread gets picked up, or if the seed grows (or fill in your preferred metaphor here…).

And then we were joined by Lisa Davis. I found our discussion this week enormously rich, if also genuinely challenging. Professor Davis called Favret-Saada’s text a “polemic.” And one feels the force of her opening gesture in the chapter we read: the author explicitly denounces that kind of anthropological knowledge production which moves from the comforts of a well-guarded (an epistemically distanced) subject position. And there is a suggestion that it is not merely “witchcraft” that cannot be understood from such a position, but indeed that perhaps no aspect of human meaning-making can be truly illuminated on such terms.

What is the alternative? It is, frankly, a little scary, at least in this context: one must “wager oneself.” One must be willing to put oneself at risk (see lower left of the board picture above). Fear follows just behind.

I suggested toward the end of class that this formulation (that we are or must be “wagered” in the pursuit of knowledge) had something in common with Gadamer’s treatment of understanding in Truth and Method, where we are reminded that understanding is an “event” and that is only possible when we make ourselves available to actual transformation in the course of the encounter (with a text, a person, etc). Gadamer treats these matters in connection with the problem of interpretation, generally in reference to the reading of, say, a poem, or an archival source. Are there stakes in such encounters? To be sure! And yet, the direct peril to which Favret-Saada subjects herself in the pursuit of witchcraft knowledge takes the matter of the “risk” of understanding to a different level. She is literally inserting herself in a belief system, and a series of practices it would seem that are death-dealing. Directly death-dealing.

That is pretty intense. Maybe even scary. It may set a kind of radical limit case for whatever it is that might be other than the “safe” (if perhaps also forever slightly unsatisfying) project of “knowledge”— of the kind that works exactly because one keeps the distance between oneself and the object of knowledge (in connection with all this, some of you might find Carlo Ginsberg’s interesting book on distance of some use).

-DGB

* * *

[FP notes follow, with VB a little further down]

Before proceeding to brainstorm some ideas for what our final project might be, we kicked off this class by placing (what I think was) a wooden spinning top in the center of our table. In looking at the swinging artifact crowning the desk I couldn’t help but thinking of Nolan’s film Inception, in which a spinning top is used by one of the characters to check the difference between dream world and reality: if they spin the top and it stops and falls, they know they are awake; if the top continues to spin indefinitely, they are in a dream. The film’s ending shows a top spinning but the screen cuts to black before the audience knows whether it will collapse or not, inviting speculation as to whether the scene is real or part of the character’s dreams and, therefore, hinting at the possibility of them being trapped in an endless time loop.

The conversation about potential paths forward for our final project felt a bit loopy (is that a word?) or paradoxical as well… We are all gathering around the idea of interdisciplinary work, yet there seemed to be some fear that the diversity of our backgrounds might pose a challenge for building the sense of community and equal belonging that is necessary in order to pull off the assignment. At any rate, some stimulating proposals were discussed, and we opined that some anxiety at the possibility of not finding common ground is actually at the core of what any interdisciplinary endeavor represents. So the overall vibe seemed optimistic, I would say—we’ll just have to ride the spin! (If the metaphor is allowed…) Professor Burnett introduced a concept that he attributed to Keats that I really loved: negative capability. As I understood it, this would be the capacity for thinkers to embrace intellectual uncertainty as opposed to rigid conceptions, and is what eventually fuels the notion of interdisciplinarity.

All this happened before we were loudly interrupted by the government alarm test—and, speaking about interruptions, I’ll venture to ask whether interruption could be another topic to consider for our final project? As a composer of music I think a lot about interruptions: what they are, and what interrupts what, and what is the effect of said disruptions. This seminar is in a way—for me, anyway—an interruption of our daily practice, a “letting in” of the other. Is that a shared feeling? And if yes, is it powerful enough to become a theme for us? In reading Christy Wampole’s article the previous week I thought about this as well. Besides working as echos, comments, or amplifications of the text that contains them, the illustrations in books sometimes function as interruptions of some sort: a mandatory stop on the reading process that opens a window into something else. Prof. Wampole’s visit felt too short, and I couldn’t get to ask her what she thought about this…

Luckily, Elizabeth Davis’s visit this week felt less rushed. Before Prof. Davis came in we had spent some time with Carrie Lambert-Beatty article on parafictions, and both this article and the one by Jeanne Favret-Saada that Lisa offered us (Deadly Words: Witchcraft in the Bocage) helped us problematize the notion of belief within the broader discussion of what forms of knowledge (theory, expertise, experience, belief) relate to our respective disciplines. The discussed concept of “situated knowledge”, the idea of a knowing that demands an experienced/embodied vision, felt to me relatable to the artistic medium, or at least to how practice-based arts are situated within academia. Musicians, for instance, to a large extent learn by doing—which is not to say that observation, measuring and analysis don’t have a place in their instruction, but rather that the bulk of their expertise is developed by means of an embodied, pre-theoretical experience (in turn putting the arts in an oblique, conflictive relationship to the knowledge production project, as was [succinctly] discussed with Gavin Steingo on week 2). Sometimes it feels like I am getting a PhD in what may look like witchcraft for many. Oh well…

What else? Many more mentions of the word “fear”. Might we have another theme there?

-FP

[VB follows]

As I went through my notes to work something out for the task of comprehensively describing this Wednesday class, something about the early discussion we had popped-up into my mind in the most nonlinear way. In the preamble of the class, while DGB waited for the seats to be filled, a conversation on the multiple ways of taking notes took place. Huut pointed out that the class follows a very nonlinear structure that could somewhat be transcribed via Obsidian. When DGB asked what that would be, Huut showed us on his computer, this note taking application that turns linear notes into constellations of concepts or mental maps, something that he believes could help us grasp the content of the class in different ways. (I reckon that, as averse to technological experiments as I am, this way of taking notes would indeed work better, as linearity is not capable of reproducing the richness of ways this class takes). As the discussion on note taking went on, SM proposed as a final project the possibility of us, collectively, engaging with note taking in a somewhat anthropological way. This had been done in another class she took with great success. At that point, CB proposed as a final project taking notes on the class and mixing it, in a creative and parafictional way, with unreal notes. This idea touched DGB, who is particularly involved with projects that play around and with the idea of reality/fiction. He then proceeded to show us projects that had been done over the past few years that engaged with the question of parafictionality – following the topic of Carrie Lambert’s article assigned for this class. One of the projects, done during the first year of the pandemics, proposed a syllabus for a class to be taken in 50 years time, on the topic of food and coronavirus. For each article or book in the syllabus, the students wrote a short abstract on the topic of the book. The interesting point here is how they managed to mix in an indissociable way both fictional works – pieces that they imagined could be written about covid in the next fifty years, with real works that also engaged with the broader topic of food, history, future, etc.

The class moved on nonstop to our conversation with Lisa Davis. Professor Davis proposed as readings for this week the book Witchcraft in the Bocage that she teaches in her course of introduction to anthropology. According to her, this is a course in which she needs to weight the pros and cons of canonical texts in anthropology, since this field is particularly embedded in colonial history. In this sense, she points out that she needs to decide carefully between the good and bad legacy each anthropological work carries. In that aspect, SA raised a question about the potential racialized reading of Evan Pritchard’s expression, quoted by Favret- Saada “thinking black and feeling black”. As the professor recognized the racialized background of this expression, she also pointed out that it has been interpreted as an anthropological approach toward its object. In other words, it has been understood in regard to the positionality subject-object, and how this relationship, as well as the relationship with the knowledge that is sought, involves risk as a key element. Be it to move towards it or away from it. At this point, even if escaping the chronological intention of this write-up, I would like to mention DGB’s intervention regarding that aspect. Towards the end of the class, DGB explained, in a much more logical way that I can reproduce here, that understanding is letting yourself be affected and transformed by the knowledge you acquire. This to me seems to be the nodal point that unites most of our discussion: there’s a relationship between knowledge and experience and affects that is and has been ignored by the knowledge making process as it happens in academia. As DGB pointed out, what the method does is, among other things, interpose itself between subject and knowledge and, by doing so, it offers a safe space for this subject to inquire about the world. There’s no risk involved in the way we produce knowledge in academia and, for that, all we can do is reproduce the same images of a disenchanted world.

– I know there’s much more to say about the class but I feel that I covered what for me were the most important and interesting moments of it.

-VB

SEMINAR 6: w/ guest Karen Emmerich

In a departure from our usual order of things, our guest joined us for the first half of this session. This meant we jumped right in with both feet on a set of genuinely fascinating questions brought to us by Professor Karen Emmerich from Comparative Literature. For starters, Professor Emmerich sketched the effectively “interdisciplinary” nature of her own professional identity: her department is Comparative Literature, and she is 100% a scholar in that field (indeed, she will soon be president of that field’s professional association); at the same time, she has a strong affiliation with the “regional” (and also linguistic) domain of “modern Greek studies,” which is not a department (worth thinking about why there is no department of “Greek” in the same sense that there is a department of “French and Italian” or “Spanish and Portuguese” — and, wait, did there use to be separate departments of French and Italian? There did — indeed, not long ago…), but is certainly a coherent academic project, and even has “program” status in various places. And finally, Professor Emmerich is very active in “translation studies,” which is also not a department, but is program at Princeton, and is certainly a very large and important area of literary/scholarly work where questions of theory and practice are alive and there is lots of work to be done.

We took a loop out on what we have come to call the “low road” (shorthand for the nuts and bolts and ground-level features of disciplinarity / interdisciplinarity) in a conversation about professional associations themselves — the way they work in the academy, their status in the sociology of the profession. But Professor Emmerich was quick to take us into the core problems that constitute (and bedevil) comparative literature as a field.

Prominent here was our discussion of “comparison” itself. It was clear from the Shih reading that the field experiences a kind of traumatic discomfort with the very idea of a comparative method. Shih sets out from the assertion that all comparison is effectively invidious, in that it is always already evaluative and inevitably sets the conditions for rankings and assertions of hegemony. By these lights, comparison is the handmaiden of imperial/colonial power, and inextricable from legacies of violence, both ideological and direct/embodied/material.

I personally expressed quite a bit of resistance to this notion, which seems to me false as a matter of logic — even if true insofar as it pertains to the history of literary comparison within university settings. But I feel it is very important to make the distinction. It seems to me not at all correct hat all comparison conduces, ineluctibly, to ordinal sorting. On the contrary, comparative methodologies have a longstanding connection to the study of “form” as such, and it would not be wrong to say that the modes of abstraction that tend to emerge from the work of comparison are essentially homologous with the very idea of an “idea,” such as that term gets thrown around in the diverse intellectual traditions that take an interest in Plato, Aristotle, etc.

Let me be clear: I’ve read Orientalism (indeed, Said’s work was very important to my first book). I am not denying the imbrication of Anglo-European literary scholarship and the larger ideological program of empire. I am merely insisting that one can do comparison with an eye toward things other than deciding “who is greater” or anything along those lines. One can do comparison for the purpose of discerning structure. One can do comparison in an effort to identify kinds. And, indeed, one can do comparison in the hopes of having an idea.

To be sure, structuralism, systematics, and conceptual abstraction itself all have much to answer for, and each can be shown to have participated in political programs we would now repudiate. But it is also the case that these are fundamental practices of reason itself, however construed, and I would be very interested if you believe that any one of these modes of thought is essentially “corrupt” or, say, “culpable” in an absolute, context-independent way. If you do, let’s talk! Perhaps I am wrong here…

*

Context. We spent some time on this notion. On the forms of equality or equalization that are achieved through contextualization, and those that are achieved through the erasure of contextualization. A very definite preference was expressed for the latter. Although Hayden White has some very interesting things to say about a propensity for contextualist modes of argumentation (NB: he associates them with an essentially “ironizing” intellectual orientations). There was a ringing moment, nevertheless, when Professor Emmerich expressed, as I heard her, that she committed to comparative literature as an alternative (a respite?) from the “ethnonational” study of literature.

*

The last part of our session with our guest focused on the status of the literary work (as distinguished from the literary text) as an object of study. I expressed some misgivings in relation to the Shih framing of the problem, expressed here in my marginal annotation:

Obviously this was on the polemical side, and conversation ensued about the importance of demystifying “the literary” while activating a sensitive critique of the ideological work this mystification has performed. This was good stuff to get to, not least on account of the considerable number of the folks in the class who hail from departments built around the study of language and literature.

There was a very moving (to me) turn, in closing, to the issue of translation, and to what it would mean to have the work of translation be the work of academic scholarship itself (whereas it is mostly, these days, treated as a kind of poor relation, and younger scholars are often encouraged to focus on “original” work). What clearer way to see the cost of the current “scientistic” model of knowledge production within the modern humanistic academy? After all, much learned culture, in many parts of the world, across much of human history would have understood translation to be the highest form of scholarship...

-DGB

* * *

[SM and CB notes are below, SM first…]

Part I

“In a moment of frustration,” as he put it, DGB wrote the following note in the margin of Shu-mei Shih’s “Comparison as Relation”: Is power even the most interesting thing to be thinking about using literature?

When I took Wendy Belcher’s course on writing journal articles (see her cool site here), I learned that Homi Bhabha’s short introduction to Simone de Beauvoir has—according to certain metrics (and how do these things really work, anyway?)—been cited more than any other article published since 2000. As a Beauvoir person, I am not troubled by this fact (am I nonplussed by it? A bit.). But one thing that does intrigue/bother me is that ever since Foucault did his Foucault thing, the word “power” has become the most common journal article keyword in the humanities and the social sciences.

This is all to say that, to borrow DGB’s language, I was very down with his remarks. I think CB is going to write more about the first half of seminar, but here are some things I noted and enjoyed:

- DGB characterizing certain parts of our “low road” discussion as “follow the money moments”

- JN telling us about his dead disciplines reading group and saying that Classics may very well be the most chauvinistic discipline

- Reflecting on works of literature as objects that create fields of study and vice versa

- KE’s mention of the “spectre” of Emily Apter (if we had had more time, I would have like to ask about David Bellos and Apter’s ongoing debate over untranslatability and what KE makes of the whole thing. Is this a generational difference? What is actually going on here?)

- Learning about Forms

- Learning about Matthew Reynolds Jane Eyre project

- Imagining JN teaching “Why Compare?” to undergrads (and thinking about this question from R. Radhakrishnan’s article after class: “Where and how does one draw a critical line between ways of being and ways of knowing?”

- DGB asking, “Would you like to sort of blast us with a fire house of negative capability?”

- Returning to a theme that seems to be one of DGB’s favorites. I tried to note it, and it goes something like this: “The humanists hitched their wagons to the model of the sciences. After WWII, we began to think in terms of knowledge production… [interruption] peer review… [interruption] self-obsoleting… [interruption] obsessive preoccupation with new knowledge production.” Is it just me or do we keep coming back to this thesis? Could we do something with it? I have the impression that we haven’t talked through these “We’re all scientists now” ideas enough–nor have we dwelt on DGB’s imperative: “Find ways to not be a scientist.”

Part II

We all (I think) got excited at the idea of doing a project around interruption(s). And also corruption. But this was at the very end of class. I am going to try to reconstitute what took place first.

Key, pressing question: What happened to the geographers?? Here’s one answer, but we need to look into this more closely. Also, why does Berkeley get to have all the fun departments? Why can’t we have rhetoric?

We went far down the low road and learned:

- That the are different types of chairs (high and low, honorific, administrative…)

- That the tenure process is quite convoluted. Or so it seemed to me. There’s a lot of letter writing and then there’s this thing called “the committee of three,” but it’s actually made up of six people?

- That you go UP or OUT

- Loads of other stuff, but the board was erased and no photo taken. And that means that maybe there’s no record of our knowledge production besides what we’re writing here.

- Oh! We also learned that there was a faculty piñata party with goading of timid children involved.

Eventually DGB left us a little early (and much too late to play proper hooky). We then brainstormed. It seems like we’re still interested in the idea of negative capability. But we’re also worried that we’re thinking too much about the concrete outcomes of our project (What will it look like? Will it be on Obsidian?) and we haven’t spent enough time thinking about the idea or theme we’d like to explore.

SA sent us all a Google doc so that we can keep brainstorming. We did not come up with a plan about how to proceed exactly, but it sounds like we’re all going to jot down thoughts/link to inspiring projects.

We also discussed meeting again on Wednesday the 25th after class. And we didn’t get to talk about agnotology—hope we can next week!

-SM

[CB follows]

We all sat in chairs as we learned what it meant to be promoted to chair versus to be administrative chair of a department, and eventually, with all this talk about (and all this sitting in) chairs, “chair” started to mean nothing to me. Semantic satiation took over and I started to laugh. I wanted to say out loud why I was laughing, to explain that it was not about anything being said or at anyone, but just that the word “chair,” despite all of the new meaning it was gaining, was temporarily a just a couple of phonemes. Although we did not get to discuss the reading on agnotology (the cultural production of ignorance) I felt that this moment metaphorically captured the spirit of that idea. It is not a perfect parallel, but it felt like a “the more you know, the more you realize how little you know” moment. As we learned about chairs, I lost all sight of what “chair” meant, and in the process the idea of ignorance–and different manifestations of ignorance–was highlighted.

At the end of class we discussed our project, and I just wanted to acknowledge my classmates’ congeniality, respectfulness, and willingness to listen to each other. This kind of thing is not guaranteed in any group project, and so I appreciate the generally positive attitude. And when someone expresses (understandable) concerns, it seems that there is always someone else ready to provide encouragement.

Going back to the first part of class, our guest Prof. Emmerich, who works on modern Greek came to us from the Comparative Literature Department. A few topics of conversation included the concept of “area studies” in universities, the purpose and dangers of comparison across cultures, and translation as scholarly work that adds (perhaps more than original work?) to knowledge production/a body of knowledge.

Prof. Emmerich is a proponent of translation, and I found something she said on this topic especially inspiring (and placating): “One can start at any place.” [See this on the photo of the board, above! -DGB] That is, “each instance of the work [any translation into any language] can be taken as a starting point to interpret it.” She argued that even though nuance may be lost in translation, translation is also always more. If you can’t translate a word perfectly, or the meaning gets misconstrued, rather than thinking of that as a loss, we can think of it as a boundary where languages meet and do not cross, but the translation still provides more (more what? Knowledge? Opportunities? Something else?) than if it had never been translated.