By Maia Hamin

Photos by Matthew Miller

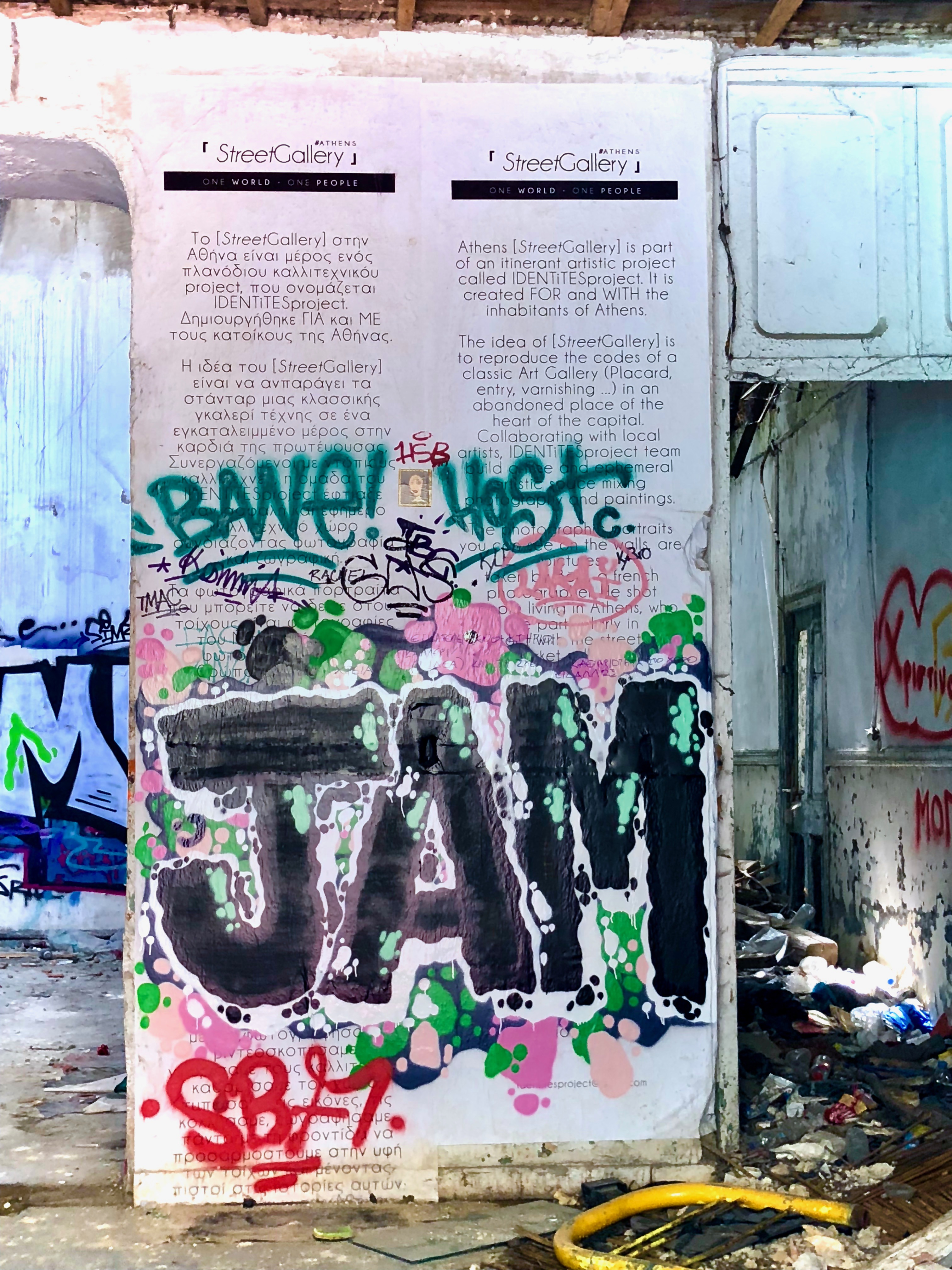

ATHENS, Greece — Just around the corner from a 900-year-old church, the graffiti-covered entry of Scholiou 4 gapes open. Inside, neon spray-paint eclipses murals on the walls and flies buzz around the trash piled in the rooms’ corners.

Decaying furnishings — a couch, an office chair, a lone traffic cone – dot the rooms. Sections of the roof and floor have caved in, revealing bright sky above and tarnished copper piping beneath. The conditions make it likely that, as an inscription on the wall promises, the “itinerant artistic project” that the building once housed has long since moved on.

Evolving Art in Scholiou 4. Photo by Matthew Miller

Decaying furnishings — a couch, an office chair, a lone traffic cone – dot the rooms. Sections of the roof and floor have caved in, revealing bright sky above and tarnished copper piping beneath. The conditions make it likely that, as an inscription on the wall promises, the “itinerant artistic project” that the building once housed has long since moved on.

An office chair with a message. Photo by Matthew Miller

Any street in Athens is likely to meander past a few empty-eyed apartments or dusty storefronts, relics of a real estate market only beginning to recover from the nation’s long-running economic crisis. The ruined buildings stand out among the vacancies, their paint peeling, windows broken or boarded up, roof dipping precariously low. Derelict properties like Scholiou 4 are far from rare in the Greek capital.

The entrance to the Street Gallery. Photo by Matthew Miller

In 2014, the municipal government and the Organization of Athens unveiled a plan to incentivize owners of the more than 1,200 abandoned buildings in Athens to rebuild or demolish the structures. Vivi Batsou, the head of the Organization of Athens, was quoted in the Katherimini newspaper describing how the first step was “to create a process by which we can locate all the owners and make them an offer.”

A collapsing portrait from the gallery. Photo by Matthew Miller

The call for the creation of such a process was not simply convoluted marketing-speak. Greece is the only country in the European Union that has yet to finish its cadastre, a national database of property boundaries, ownership and associated documents. Without a searchable cadastre, the process of locating the owners of a ruined building like Scholiou 4 requires navigating the labyrinthine bureaucracy of the Greek land registry system.

Photo by Matthew Miller

Asked how such a search could be accomplished, Stratis Sourlagas, a landlord in the city, responded with a laugh. “That’s a tricky question,” he said, suggesting that the answer might be found at the Land Registry for the city, housed in the Athens Department of Urban Planning. They are not too organized, he cautioned, “even for the Greeks.”

Even knowing its address, it’s easy to walk past the Department of Urban Planning. The windows are criss-crossed with rusted diamond-shaped bars that render it nearly impossible to see inside, and two flags over the doorway are so thoroughly faded as to be nearly unrecognizable. Inside, a folding table serves as a reception desk, where on a recent afternoon a seated man with a gray ponytail argued with a woman in a yellow headscarf.

In a larger room behind the reception area, two men sat behind ancient yellowing desktop computers, and a third, older man presided over a row of six paper bins that held a variety of applications and forms. A tall, harried-looking man shuttled leatherbound volumes between a row of shelves and a long table in the back where visitors sifted through dozens of delicate paper documents.

A collapsing section of the gallery. Photo by Matthew Miller

Some people rose from a paper-covered table with a single sheet clutched in their hands, while others walked out with an entire sheaf of documents tucked under their arms. One man walking away with a stack identified himself as an architect. Having just spent at least 15 minutes leafing through a hefty pile of documents, he asserted that he was much too busy to talk. He promised, with an ironic smile, that looking around the office would provide more than enough insight into the operation.

The task of finding the owner of the abandoned building at 4 Scholiou turned out to require something of a team effort. Billy, a heavyset young man with a policeman’s flat-top haircut, rose from his computer to furnish the correct form for a title request, asking for the address of the building in question.

Before the translated address could be copied down, a visitor who overheard our conversation stepped up to argue with Billy in rapid Greek about the correct provincial identification for the address given. With the aid of Google Maps, an accord was reached, and the correct address was written in Greek on the form.

One of Billy’s colleagues inked a numbering stamp and marked both the request form and a page in a leatherbound book. The book seemed only to contain one request number stamped after another, ordered chronologically and ascending neatly in value, for purposes unknown.

Billy explained that to obtain the building permits and title for a property, you must get its construction identification number from another ancient desktop. An unamused man with a runny nose sat down to peck the address into the lightly-humming computer, and handwrote a number on a slip of paper for Billy.

Billy carried the construction identification number to the man who supervised the leatherbound records. He spoke in rapid, frustrated Greek, and Billy sheepishly asked in which decade Scholiou 4 was built. Another Google Maps photo was consulted, and several employees and visitors gathered around to argue about the architectural style of the trash-filled ruin.

Graffiti at abandoned building located at Scholiou 4, Athens. Photo by Maia Hamin.

Suddenly, the man who minded the books handed back the phone and wandered into a back room without another word. People begin to shuffle towards the exit.

Billy, apologetic, explained that it was 1:30, and the office was closing. He promised on the walk out that the request could be resolved tomorrow, and stressed the importance of bringing in the title request form, which currently bore no information other than a requester’s name and the building address.

The helpful visitor from before was also walking towards the door, and rejoined the conversation to remind Billy that it was, in fact, Friday.

Monday, Billy corrected hastily. Come back Monday.