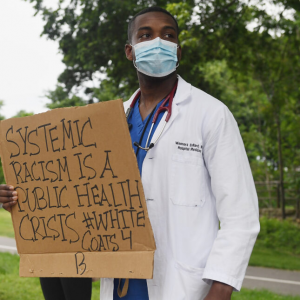

Source: Michael B. Thomas/Getty Images

Note: Mentioned sources are hyperlinked for ease of reference

RN: Registered Nurse Anne, NA: Narrator, Prilutsky: Michael Prilusky, S: Dr. Shelton, NIH: NIH Clinical Researcher, SR: Surgical Resident

Part 1: Introduction

NA: Hello, on today’s podcast for Critical Perspectives in Global Health & Policy we will be discussing the impact that the rise of racial tensions in the wake of the covid-19 pandemic has had on the American Healthcare system

NA: 2020 has been a crazy year

[sound bits of COVID-19 news reports, BLM]

NA: And amidst all this chaos, Αmerican society has undergone a collective awakening regarding the pervasive nature of racism. Every structural institution in society has been affected, and the health sector is no exception

[ COVID disproportionately affects African Americans and communities of color news report]

NA: The additional burden caused by this pandemic has only served to exacerbate the issues faced by frontline workers and has placed the healthcare system in a position of extreme strain. This has forced many healthcare professionals to experience unprecedented amounts of stress in a nation where such a level of death among previously healthy individuals has never been witnessed before. Many experts in the field have attested to this trend and emotional toll.

NA: Our first expert is Michael Prilutksky, president of Jersey City Medical Center

Prilutsky: And to have such a high level of mortality was extremely traumatic, and again, not uh nevermind workload and unload. It’s just the patients dying was incredibly tough on the team

Prilutsky: People were putting in extra shifts, as we ran short of staff and the workload, the ratios, the expected outcomes increased per each employee. So again, they were stressed out, not only facing the increased workload, but facing a lot of unknown as to how it’s going to affect me

NA: This sense of stress and overall frustration seems to be uniformly experienced amongst every medical professional that we have spoken with spanning all levels of the national healthcare system.

NA: After interviewing a current surgical resident, we received this remark:

SR: There’s also a lot of emotional fatigue from the pandemic going on and the kind of acceptance of the public of the pandemic and either refusing to accept that it exists or not following safety protocols and going out and having parties or having big dinners or wearing masks and it’s a big emotional toll knowing that were in there working that you know, our lives are being disrupted that we’re putting our lives at risk and people aren’t doing basic things that they could be too slow in order to help.

NA: All this said, there appears to be an underlying trend in the distribution of this year’s burden. Minority healthcare workers have seemingly faced the brunt of these dual pandemics, structural racism and COVID-19, especially within the healthcare sector.

Part 2: Introduction Contextualization in Data

NA: People of colour make up a significant proportion of the healthcare force. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, minorities account for about 28% of all healthcare workers.

NA: While the representation of minorities in some parts of the healthcare system are more balanced, there are still substantial racial disparities and under-representation in the field at large.

NA: As a result, the personal experiences of minority healthcare workers tend to be excluded from the overall medical racism narrative, even though the discrimination they experience is extremely real. Today, we seek to shed light on the challenges faced by people of color in the medical sector, by sharing their perspectives, personal experiences, and understanding of medical professionals spanning all levels of our healthcare system.

[Transition Music]

Part 3: Getting into Anne’s Story

NA: In the remainder of this podcast we will be discussing the very personal experiences of Anne, a registered nurse who finds herself faced with the dual burden of the COVID-19 pandemic and racial injustices of the modern healthcare system. All the while, we will continue to draw on expert opinions to further this story

RN: I always come to work dreading like you know I really don’t want to be there but the only thing that’s you know keeping me up and going, is how to pay my bills and how to provide for my family. And somebody will say well why don’t you quit, and then go to another facility. And this, the problem of racism in the state that I’m in right now exists everywhere you go.

NA: This feeling of entrapment is an all too common narrative experienced by many POC. But, in this particular instance, Anne is describing the effects of living through managerial inequity directly imposed on her due to her ethnicity.

RN: Because of the color of my skin. Everywhere I go, it will be the same thing because we have hospitals over here that I have friends all over, and they’re all complaining about this same issue. So, the mindset over there is all over the place. That’s why, you know, I just close my eyes and just go to work. You know I like what I’m doing, taking care of people, people who cannot take care of themselves. I go into the room, even though all these things are going on in the background, I just try my best to take good care of my patients.

NA: Despite Anne’s efforts, the system in which she works is designed against her. From the hierarchical power held by the predominantly Caucasian management to the constant undermining of her abilities by fellow medical professionals simply due to her ethinic background, these systems have enabled the perpetration of structural violence against her just as Paul Farmer describes in his work, On Suffering and Structural Violence.

Part 4: General Overview of Inequities Before and After COVID-19

NA: The compilation of the effects of structural violence and systemic racism have created a system in which people of color have been repeatedly exposed to COVID at rates disproportionately higher than their Caucasian co-workers. Despite people of color comprising the vast minority of healthcare workers, they make up nearly 62% of the deaths attributed to the virus amongst medical professionals. This trend was also observed in Anna’s workplace experience.

RN: So, you know with the COVID, like, when COVID strikes, initially, the first person who had a COVID patient was a white nurse. I mean, they couldn’t help it because she was the only one with the empty bed at that time that she had to get a COVID patient.

RN: So she was the one who got a COVID patient at that time. And then subsequently, we the black nurses like, every single day that we come on the floor, we will be the one having a COVID patient. Some people on the floor went a whole month without even having a COVID patient to take care of, you know, meanwhile, all the black nurses on the floor are being exposed. Every time you come in, you have to get a COVID patient, while all the white—caucasian, whatever you called it—like they are walking around with no COVID patient for maybe a whole month.

NA: To better understand these COVID patient assignments, we turned to the field of psychology.

S: I’m Nicole. Shelton, I am professor at Princeton University. I’m a social psychologist by training and I study inter-group interactions.

NA: We probed Dr. Shelton on the unequal distribution of labor displayed between the caucasian nurses and nurses of color in Anne’s story. At first Dr. Shelton’s reaction was that of surprise to Anne’s situation because it seemed to be contrary to the literature.

S: There’s a model by Susan Fiske called the stereotype content model. And in that model she has or with that model has shown that minorities—so ethnic minorities and other minority groups—are often stereotyped as being incompetent, whereas whites are stereotyped as being competent.

S: I would have suspected that minorities would be assigned less complex cases because complex cases require competence and if you are perceived as being incompetent, then you wouldn’t get those complex cases. So it’s a little counter and the observation is a bit counter to the stereotype content model.

NA: In social psychology, the model in which Dr. Shelton describes postulates that all generalized stereotypes form along two different dimensions: competence and warmth. In the case of Anna’s experience, we examine the stereotype content model as it applies to race and ethnicity. As Dr. Shelton explained, the observation that nurses of minority status were being loaded with more complex cases is counter to the stereotype content model. However, this observation fits with the general trend observed throughout this pandemic that harkens back to the racially motivated myth of Black Immunity and the superhumanization of black bodies.

NA: At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, myths emerged claiming that African-Americans were immune to the virus , due to the melanin in their skin. While puzzling in retrospect, these myths surrounding Black immunity are not unique to COVID-19. False theories relating to the African-American community’s immunity to illnesses became prevalent in the 18th century. For example, Dr. Benjamin Rush, a prominent signatory of the Declaration of Independence, used the myth to justify the recruitment of the free Black community in Philadelphia to care for white citizens in the treatment of Yellow Fever despite a similar mortality rate among both communities.

NA: This belief in Black immunity is also observed in social psychology as superhumanization of Black bodies. It is the idea that Black bodies possess supernatural physical and magical attributes. Researchers have identified a paradoxical connection to the belief in superhumanization with African-American incompetence. These observations could help reconcile the apparent incongruity between the stereotype content model and the labor distribution that Anne experienced.

Part 5: Demographics, Cliques, and Hierarchies

NA: Now, to describe the unequal distribution of labor, it is necessary to further explain the hierarchical structure of Anne’s nursing unit.

RN: So what they do is sometimes we will be discharging patients back-to-back. And then, you know, the people who are favored will be discharging people at the same time. But you see that they will always, always try to fill out our—you know the minority people’s—beds, seven before they start filling theirs, you know the favored ones or the people in the clique, their beds.

RN: So if you are a minority on the floor you are always overwhelmed. But the day the table turns to their clique, [they’re] having more, you know like, having more admissions, you will see all of them running towards them–helping them and then, you know, doing most of the stuff for them. But when it comes to our own, no one comes around to help. You call them, they’re all busy.

NA: This feeling of isolation is only compounded by the fact that the majority of the managerial staff on Anne’s unit are caucasian.

RN: People don’t talk about how they feel, to the manager or you know assistant manager because they don’t want to step on their, you know, step on their foot the wrong way. And they don’t like what’s going on but they are scared to talk about it, you know.

RN: Sometimes you might need days off, and because you are not in the group, or you are the target, they always give you a push back.

RN: You come to work—the way they talk to you—like they really make work uncomfortable for you. They will really come after you. Things that are irrelevant for them to you know come after you they will come after you for that and nursing . . . It’s easy for people to set you up so everyone’s just really scared of coming out to say something against them.

NA: To further understand the in-group behavior described by Anne, we turned back to Dr. Shelton

S: There’s research in general that shows that people tend to interact with others who are quite similar to them—so that applies to race, it applies to age it applies to religion, you know, you can pretty much insert any any group there and you will find data showing that people tend to interact more with people who are similar to them.

S: You know, sometimes it’s related to bias, but more often. It’s just what people are comfortable with. Right. It’s really what they grew up with. They’ve been socialized in a predominantly white neighborhood or predominantly ethnic minority neighborhood. And so those are the people who they feel comfortable with. And so then when they go on to a work setting, those are the people they feel comfortable interacting with. I’m not saying that that’s the right thing, or it’s the wrong thing, but that’s that’s findings that we know from the literature.

NA: As described by Dr. Shelton, the tendency for in-group interactions is commonplace. And it may help explain the formation of the clique Anne mentioned. However, the situation becomes problematic when the partiality shown by management to individuals in the clique directly impacts the health and well-being of out-group members such as Anne and other minorities.

Part 6: How Complaints Have Been Handled in the Past and Administration getting Involved

NA: Sadly, this unfair treatment also occurs when black nurses point out the injustice they are experiencing and issue formal complaints.

RN: My other colleagues that took some issues to HR and others were like, you know, with my manager will be like–brush it under the rug. She would take the initiative to do something to let the stuff go away and talk to people and minimize the way things are going. But, you come back the next day and it’s the same thing all over again like it keeps on happening and happening. So it makes you wonder. Did she even take the initiative to talk to the people to change their attitude, the way they talk to you know the black nurses–the way they make assignments . . . Sometimes she will, blindly defend them knowing that what’s going on is not right.

RN: “So basically there’s a lot of bias on the floor, but the bias, you know, is in grades. But when it comes to us, you know, the black nurses, even when you talk, they look at you with the impression: “How dare you question me”, you know, in their head–the way they respond and then they just, you know, brush you off. Like, you don’t deserve to ask them questions.”

NA: Fortunately, the increasing awareness of racial inequity following the Black Lives Matter protests this past summer has caused Ana’s hospital to reckon with its biased policies, as well as listen to the voices of minority nurses–voices that have previously been silenced and minimized in the past.

RN: Coming to the George Floyd issue, and how it’s opened everyone’s mind and eyes to see that yes racial discrimination exists. Our hospital put in a policy. They have a Diversity Committee that’s looking through all that, you know, issues. And now, our president—the president of the hospital is not taking it lightly. So I guess it . . . It kind of puts a lot of fear in them right now, that when they are doing stuff they have to be very careful on how they act and how they talk to people.

NA: One of the first steps that Ana’s hospital has taken in order to combat system-wide inequalities in the distribution of tasks among nurses is introducing an Acuity tool. This new acuity system allows for each nurse to score their patients’ pathological severity for each upcoming shift and relay the information to the charge nurse, allowing for an equal and unbiased distribution of patient care-load.

RN: After the complaint on unfair treatment they instituted an assignment committee that we are working on right now. And you know, we kind of have been having a push back on it. With our acuity tool, so that when they make assignments, it will be fair. And in actuality, my friend in California, who is in the same as I am right now, is using the same tool to do the assignments. And she said, it really works really great that, you know, anytime she works on her floor the workload is not heavier than when she goes to the other floors. She can see the difference when people don’t use the acuity tool to make assignments.

Part 7: Acuity Tool Pushback

NA: Despite its ability to create more equitable shift assignments, Anna says there’s been a lot of pushback against the Acuity tool:

RN: Well, according to the charge nurses, they are doing the assignment, the same way. So, there’s no reason for them to do extra paperwork, because that takes a lot of time. We have to go around like all nurses have to fill out the type of patient they have. And after each shift, you have to give it to the charge nurse. The charge nurse has to go through the acuity tool, and then split the patient, and I guess that’s too much for them. That’s why they are trying to avoid doing that. But then we collected that data for three days, as they do it without the acuity tool and then using the acuity tool. We were able to determine that, you know, using the acuity will help because you could see that one person has an assignment which is really not balanced.

NA: Anna then described how puzzled she was that she and her colleagues even had to do this data collection in the first place.

RN: So, um, I mean even collecting data for this issue I don’t think is even relevant for us to go through and collect data. Other people have tried it in their work and it’s worked. It’s research based, and that’s what we have to put in place and do it. But because they want to have a push back, push back, push back so now she’s just like, you know, we have to collect that data and find out, you know, whether it’s gonna work or not to work. But in the healthcare system, everything is scientific base or database oriented. So if people have already done it, it’s worked and it’s helped them.

NA: Next, we asked Ana if she thinks the acuity tool would ever be implemented.

RN: – I mean, I, my perception and how I see it on the floor, the charge nurses don’t want to do it because it’s not going to favor them on how they distribute the assignment to the cliques, because if they use an acuity tool, you cannot come early in the morning and switch the patient and then, you know, switch a heavy patient on your assignment and give it to somebody and then take that person’s lighter patient and then keep it. So they’re doing everything possible not to make it work.

NA: We then asked Anna if she thinks the managerial staff is aware of the discrimination she and her colleagues of colour face.

RN: I mean, they are not feeling it, so they ignore the fact that the problem exists. And if they don’t, if they don’t recognize that there’s a problem, then they are not motivated to do anything to help solve the problem.

RN: So I think it doesn’t affect them. And that’s the reason why they don’t recognize that this situation exists. You have to really be in a person who’s feeling the pain’s shoes for you to be able to realize that things are going wrong, but it’s not that. They come to work, you know happily, because they can switch stuff all over the place that’s suitable for them, and they relax when they are over there, whereas other people go through anxiety and panic mode and everything when getting up in the morning to come to work.

RN: (So, I think first of all, my manager is supposed to recognize that, yes there’s the problem of unfair assignment. Until then, she thinks she’s in line with the charge nurses thinking that everything is right, meanwhile it’s not. Everything is not, you know, black and white. There’s another color behind black and white, that she’s failing to recognize.)

NA: Is it unusual that the white managerial staff could not see the discrimination happening right in front of their eyes? Here’s Dr. Shelton again to help answer this question:

S: I don’t think it’s unusual. I think the literature. There is some literature that suggests that this makes perfect sense. And people

S: Who are not members of traditionally stigmatized groups.

S: Or less you know those individual are less likely to have experienced discrimination and so it’s often difficult for them to recognize discrimination, they may not be as sensitive to

S: Behaviors behaviors, whether that’s verbal behaviors or nonverbal behaviors that signal some form of bias or discrimination.

S: And so when their colleagues, a color are saying, you know, x, y, z happened to me they’re more likely to want to make different attributions and well it could be because someone’s I was having a bad day, not because you are a member

S: Of a particular group. And so they were discriminating against you sometimes

S: Sometimes when people have dominant groups and non stigmatized groups have had friends who have experienced discrimination those individuals are more likely than others to recognize discrimination and prejudice. So there is research showing that having out group friends does make you a bit more sensitive to recognizing on the discrimination that minority groups have experienced

NA: Unfortunately, despite all the efforts made by Anna and her colleagues, unfair shift assignments still remain an issue at her hospital today.

Part 8: Envisioning a Post-COVID Healthcare System

NA: But, the question remains, can medical institutions truly change from being agents of discrimination to both their patients and staff to becoming drivers of active advocacy for a more equitable post-COVID future? Some, such as a surgical resident working long hours in a hospital plagued by ever-increasing numbers of COVID deaths, take a more pessimistic stance towards imagining this medical future, claiming:

SR: I think it really has pointed out some huge racial disparities, but I think most of the people paying attention to those are the people who were paying attention in the first place

NA: Taking a more positive outlook towards a post-pandemic society, Ana is hopeful of incremental change. Despite numerous setbacks, she believes the successful implementation of her hospital’s acuity tool will mark a small first step in diminishing the bias on her floor – and, eventually, across the country.

RN: We are not giving up. We are trying to push ahead. And the thing is, if nothing is to be done, then we have to go to our nursing director who is my manager’s boss to explain what we are facing. But I hope everything will be okay, and we will be able to use the tool as planned.”

RN: We brought it to their attention. And now, it’s like well, three days of collecting data to compare is not enough so we have to do a month. So we’re gonna still do it. We’re gonna push ahead and see what will come out of it.

NA: While Ana spoke to a vertical approach towards addressing the issue of the biased treatment of minority healthcare staff, we will now zoom out and see what horizontal, system-wide approaches might remedy this issue by sharing the perspective of managing director Michael Prilutsky:

Prilutsky: So clearly, if we were after population health, which we are many organizations are, as we understand that we have to change some things that we do. And it’s not about producing widgets about capitation and risk. Clearly, we knew we had to address social determinants of health with things like food, supplies and security, supportive housing, mental health, education, on the job, education, job sponsorships, because you know, again, at the end of the day, how do we expect somebody to be healthy, they don’t have a home to go to. So we had all those things in progress. But clearly, pandemic like this highlights that a lot more needs to be done. And it’s really not about necessarily diversity anymore. And we did change our focus. It is about equity. And it is about institutional racism. And this trying to understand how we ourselves as an organization, have to change internally. Versus looking always outside and trying to change to external. It’s really getting down to even looking at our hiring practices and running statistics to see if there is some baked in racism in our hiring and discipline and firing practices, do we need to educate the managers? Are we hiring too much of the like, that we are ourselves at the moment that versus the diversity that we see in our community.

NA: Ana also echoed the sentiment of a need to go beyond workplace diversity to ensure that all staff are respected and valued regardless of their background.

RN: mostly about ignorance, on the part of my co-workers, which is like the people who make assignments and the people who make the workplace, a toxic environment for some of us. I feel like those are the ignorant ones. They need to be, you know, talked to and educated on how to, you know, talk to people–how to even express, you know themselves to others and you know feel other people’s pain. It looks like those people always feel pain. How you know other people feels only when it comes to their friends and people who look like them. And that makes it a very very challenging and, you know, very stressful environment for us to work in.

NA: Ana then went on to depict these challenging and stressful times that black nurses are living in today.

RN: Anytime there’s a black nurse over there, they assume the nurse is stupid. We don’t know what we are doing, or, you know, that’s their assumption. When you talk. They don’t even, you know, like recognize you. Like me for instance because of my accent some of the doctors–one particular doctor has the tendency, always, making fun of my accent, and stuff like that. It’s just ignorant. If you have traveled to other countries–I have, that’s what I always say. I speak my native language and I learned how to speak English too. If you living in America can speak my language, and then speak English too, then you will know what we go through. If you cannot do that. You have to appreciate, you know, every other person’s background and respect them.

NA: When speaking to the changes that need to be made in terms of hiring practices to eventually develop a workplace free of the inequities experienced by nurses and all health professionals of color today, Ana described how:

RN: You need to have a balance, you know, an equal managerial position opens for every, you know, brown and black nurses to hold certain managerial positions in that place, so that it will be balanced. If you have, like, 95% of your top management are all white, what do you expect to happen. People think that you know they have the legitimacy to do whatever they want. And we don’t have any. And then they talk to the nurses–other the nurses, the minority nurses, you know, any kind of way–those people who don’t belong to a sudden claim any kind of way because the manager is okay with it. So in order to stop this kind of behavior, they need to hire people that reflect what they think–what the company stands for.

NA: Not only has the issue of racial inequities in the healthcare workforce been an issue in terms of those directly facing the risk of Covid-19 exposure on a daily basis, but under-representation of minorities within national management has persisted for years. In order to elucidate the ways that the upper levels of our national healthcare system have been working to ensure a more equitable medical future, we will now share the perspective of a clinical researcher working at our National Institute of Health. When asked what measures have been implemented at the NIH in order to improve racial equity in the workplace, our interviewee responded :

NIH: So I think for the NIH, this has been a prevalent issue for quite some years, we are far from having achieved what we need to achieve. We can only do our best work at bringing forward clinical trials and doing research by being inclusive, by bringing in ideas from people who come from all different walks of life. And that means making sure that underrepresented minorities are present. The difficulty is that we need to start this way before the time point at which people would come into the NIH which would be mostly as professionals.

NIH: But this clearly an understanding that happened way before this latest issue of Black Lives Matter. That’s been recognized that this is an issue. And I would say even from the standpoint of outside the NIH, if you apply for an NIH grant, to run a meeting, you have to show how you’ve actually tried to bring in diversity, how you’ve tried to encourage people from underrepresented minorities to be part of a meeting and that was there right before that. But that doesn’t mean that we’re doing a good job. I think people are doing the best they can.

NA: When looking towards a post-Covid medical society and the structural changes that are required to get us there, our interviewee expressed deep-seated concerns about the social system we live in today.

NIH: the question of inequities. I think we’re realizing more and more just how inequitable the system is, I think we see more and more the number of minorities that are in positions where they’re being put at risk. When we look even at a place like the NIH, those people who take public transportation versus those people who come in a private car, by taking part of public transportation, you’re, by definition, more at risk. So people who don’t have the money to have a car are more at risk- period. And that’s clearly been an issue in terms of underrepresented minorities and the inequities that we see in our system.

NA: The road towards a more equitable medical future is not an easy one, and it will take more than a few quick-fix, magic-bullet solutions in the short term. As Michael Prilutsky explains, :

Prilutsky: And it’s really not about necessarily diversity anymore. And we did change our focus. It is about equity. And it is about institutional racism. And this trying to understand how we ourselves as an organization, have to change internally. Versus looking always outside and trying to change to external.

Priluksky: But that’s going to be a long term commitment. Clearly, something that took a few hundred years to build To build up to bake over, is not going to be changed overnight. And clearly, the social determinants of health are part of the social fabric. So here too it’ll take many decades to change but again, we have to start somewhere and we have we started with education with the investment in the most vulnerable with reaching out to the community with running for example anti violence programs and education because that’s part of the health infrastructure in the cities some more to come on that but that’s uh, that again, that’s going to be not even my generation that’s going to be your generation that will have to continue to bridge that that level of inequity.

NA: This pandemic is far from over. Despite a vaccine now looming on the horizon, our nation’s healthcare workers will continue to fight and put their lives at risk day after day, week after week. While certain measures have begun to be implemented in order to raise awareness and take steps towards a more equitable medical society, they are largely insufficient. By taking a macroscopic approach to this pervasive issue throughout the field of care-giving and zooming into the lived experiences of frontline workers, we have begun to illuminate the problem at hand. However, the commitment to change cannot be short term – it cannot involve solely vertical, magic-bullet solutions. In order to create the long lasting and effective change our medical society needs, it will require the work of generations and the commitment of communities. We can fight both pandemics – Covid-19, and Systemic Racism – but a solution won’t appear overnight. Even the longest journey begins with a single step.