Music by Vincent Femia

Additional sounds from Vincent Femia and BBC Sound Effects

Script:

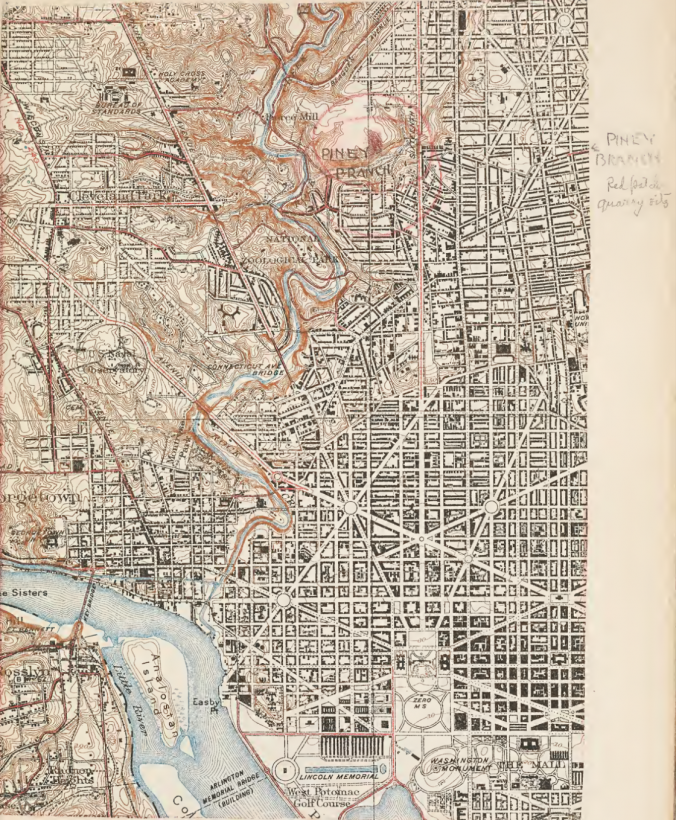

Piney Branch Park is a small wooded area roughly three miles north of the White House. It is sandwiched between the Washington, D.C. neighborhoods of Crestwood and Mt. Pleasant and it juts out east of Rock Creek Park, intersecting with 16th Street just north of the Smithsonian National Zoo grounds. If you were to make the walk north from the White House, you would pass the busy areas between Dupont and Logan Circles, the commercial strip of U Street, Malcolm X Park, and the various embassies along 16th before passing Mt. Pleasant and approaching that quieter area around Piney Branch. The park itself looks somewhat like an odd outgrowth of Rock Creek—not particularly impressive, and not particularly scenic. Houses and apartments surround the area and the 16th Street Bridge cuts through its edge. Piney Branch appears almost as an afterthought, a lazy or last-minute addition to the much grander Rock Creek Park that covers miles and miles of the city.

But Piney Branch Park and its history tell an important story. That unassuming piece of green space is an historical knot of preservation, science, urban development, and historical memory. As an old Native American quarry, the site became the battlefield of the scientific dispute known as the “Great Paleolithic War” in the late nineteenth century. The archaeologist, anthropologist, and artist William Henry Holmes sits at the center of this scientific dispute, and while he will be the central character here, this story is less about the history of archaeology than the meanings of preservation. To get a richer sense of the archaeological history, I recommend looking at David J. Meltzer’s book The Great Paleolithic War: How Science Forged an Understanding of America’s Ice Age Past.[1] But the eventual preservation of the site in the 1920s carried different meanings, for both the city and certain individuals. So, the space of Piney Branch Park represents something much richer than what would be assumed by the average visitor. At the heart of this story, then, is the meaning of preservation at different levels, from Piney Branch’s Native American past, to its scientific importance, to its environmental factors, and ultimately to its place in history over time.

* * *

Born in Harrison County, Ohio in 1846, William Henry Holmes quickly developed a passion for art. After graduating from the McNeely Normal School in Ohio in 1870, he taught painting, drawing, natural history, and geology at the school, but came to Washington, D.C. in 1871 to continue his study of art. Holmes met Mary Henry, the daughter of Smithsonian Secretary Joseph Henry, at Theodore Kauffman’s art school. In April of that year, he decided to visit the Smithsonian down on the National Mall. While sketching a bird on his visit, he caught the attention of a visiting naturalist, which led to a job sketching fossils and mollusk shells for scientists Fielding B. Meek and William H. Dall. This turn of events marked the beginning of Holmes’s winding journey of disciplines and institutional affiliations. He soon found himself working as a painter for the U.S. Geological Survey, and afterwards studying geology, archaeology, and ethnology as he moved from the Bureau of American Ethnology, to Chicago’s Field Museum, to the National Museum, and finally to the National Gallery of Art. Born the same year of the Smithsonian’s founding, Holmes came to believe that he was predestined to be a part of the Smithsonian family.[2]

At the heart of all of Holmes’s work was a deep interest in aesthetics, both the origins and development of artistic creativity. His study of Native American art and pottery became central to the Bureau of American Ethnology’s mission, but it was Holmes’s work on presumed “paleoliths” at the Piney Branch site that would give him wide recognition and fame among nineteenth-century scientific circles. Holmes was thoroughly a man of Washington science, and he imbibed on the theoretical positions of his scientific community. The head of the Bureau of American Ethnology, John Wesley Powell, structured the institution around Lewis Henry Morgan’s theory of cultural evolution. The theory posited several stages of civilizational development that moved from savagery, to barbarism, and to civilization. For the Bureau anthropologists, studying Native American cultures and peoples was akin to looking directly into the past. By ascribing the status of “savagery” or “barbarism” to different Native American groups, the Bureau ethnologists believed they were studying past stages of cultural evolution that Europeans and European Americans had surpassed or transcended. Cultural evolution suffused Holmes’s ideas on art and technology. The degree of aesthetic and artistic development in artifacts, he believed, could reveal the cultural stage of a community and people.[3]

Still, moving beyond Powell’s strict theoretical rubric, Holmes, along with several other younger Bureau ethnologists, including Frank Hamilton Cushing, believed reconstruction to be at the heart of museum and anthropological work. Replicating the construction of, say, an arrowhead or piece of art meant recreating the culture itself. Understanding technology or structure meant comprehending the creativity and invention that lay behind it. These younger Bureau anthropologists studied Native Americans not as individuals and creators, but as mindless representatives of cultural evolutionary stages. While Holmes would come to call the Piney Branch site sacred, and ask that a monument be erected to remember those who inhabited the land before the capital city existed, it should be remembered how Holmes imagined the relationship between history and culture, and the racism and othering embedded in how he thought of Native American peoples and cultures as lower occupants of the cultural evolutionary hierarchy.[4]

* * *

Today, Piney Branch Park is not much more than a series of trails among a small wooded area. The sound of cars rushing by on Piney Branch Parkway accompany the soft voices of birds that echo from the treetops. Looking down, the trails are dotted with quartz stones. Small gullies, sometimes filled with miller light cans, chip bags, and other trash, reveal layers of earth that are littered with quartzite cobbles. If you take the time to look, finding stones that appear to have been “worked” or deliberately manufactured isn’t so hard.

Oddly, no significant archaeological investigation has been carried out at the site since Holmes’s study in the late nineteenth century. Still, a good chunk of the site remains preserved. The actual age or ages of the quarrying remains somewhat of a mystery, but based on other work in the area and what is known of the prehistory of the region, it is suspected that the Piney Branch quarrying falls within the Archaic Period, perhaps dating back to 4,000 years ago.[5]

The park is a quiet place. The hum of traffic is ever present, but it feels removed. Not many people go to the park. It is easy to find yourself alone at Piney Branch for extended periods of time. You can sift through the layers of quartzite cobbles to connect yourself with the multiple layers of history. The park has been preserved for the enjoyment of local residents, but history itself has been preserved in its landscapes, in the trenches dug out by Holmes and his team, and the turtleback artifacts that dot the trails and the gullies.

* * *

In the 1870s, the American archaeologist Charles Abbott claimed to have discovered evidence of an American Paleolithic man after finding stone artifacts that resemble the paleolithic artifacts of Europe. He had found the stone tools in the bed of the Delaware River near his home in Trenton, New Jersey. Although Abbott’s claims spawned a whirlwind of theories, by the late 1880s the idea of an American Paleolithic man was an accepted fact. The assumption that undergirded Abbott’s claims was that form corresponded to age. A stone artifact that resembled the European examples of undeniable antiquity must have come from the same period.[6]

Holmes and the Bureau of American Ethnology in D.C. had other ideas. Walking just a few miles from his front door, Holmes took to the recently discovered Native American quarry at Piney Branch to challenge Abbott’s assumption. After excavating the quarry, examining nearly 2,000 artifacts much like those found New Jersey, and working through the production of the artifacts himself, Holmes argued that the crude stone tools, similar to the ones in the Delaware River, were the rejectage of the quarry, rather than artifacts from a Paleolithic age. Holmes employed the reconstruction strategies of the young Washington anthropologists to show how the so-called paleoliths were actually unfinished products. Thus, they were much more recent in origin, and the work of the Nacotchtank tribe that had lived in the area before Europeans arrived in the early seventeenth century.[7]

In journals such as Science and the American Anthropologist, Holmes deftly made his case while simultaneously dismantling the arguments of his opponents. In the first paper he published on Piney Branch that appeared in 1890, Holmes presented his arguments with certainty, and tied his conclusions to the city and to history. Holmes said, “it is literally true that this city, the capital of a civilized nation, is paved with the art remains of a race who occupied its site in the shadowy past, and whose identity until now has been wholly a matter of conjecture”[8] Holmes’s use of the phrase “civilized nation” should be understood as more than just a hierarchical judgement. It was an invocation of history, a reading of a Native American past against an urban, modern present. Holmes superimposed the teleology of cultural evolution onto the history of both the land and the city. The tale of cultural evolution, and the steady march of progress, could be revealed through Piney Branch and its surroundings.

* * *

By the 1920s and 30s, D.C. had changed dramatically. World War I had brought thousands of Americans to the capital city for government jobs. The population of DC had increased by fifty percent during the war, and by 1930, the population of the city sat at around 500,000. Urban development exploded to accommodate the population boom, and often in haphazard ways. Building and dumping intensified north of Florida Avenue, or what used to be called Boundary Street, and the areas around Mount Pleasant and Columbia Heights became dotted with new apartment buildings and other forms of housing.[9]

The newspapers and historical societies of D.C. now looked back on the land’s Native American past with interest. In 1928, the government had seized the land that is now Piney Branch Park. City and government officials questioned how the area should be preserved, and local residents and scholars began exploring its history.[10] In 1930, the Columbia Historical Society heard an address on the Piney Branch Site. Reporting on the talk and city development plans in the area, the Evening Star ran an article titled, “Historic Valley Plans Prepared: Piney Branch’s Glamourous History Recalled in Development Project.”[11] The Piney Branch site had now made its way into local natural lore, where residents told stories of its history alongside descriptions of dinosaurs and elephants of the distant past.[12] In 1935, the Evening Star ran a series that sought to tell the history of “the growth and future development of Washington from its humble beginning as a network of Indian villages, through the Colonial period, to its present proud promise as the finest and most modern world capital.”[13] The paper labeled Piney Branch a “hive of industry” before the “white man’s government came to town.” Many of the discarded stones of the quarry, the papers noted, had incidentally paved the streets of Washington.[14]

Telling the story and history of Piney Branch became a way to juxtapose this past against the urban development of the present. Reflecting on the history and the site, the Evening Star articles simultaneously looked forward and back. The preservation of Piney Branch showcased the teleology of the nation. D.C., as the capital city, could represent the nation as a whole. And Piney Branch, preserved for the nation, served as both a local and national symbol of manifest destiny, as an urban modernity filled the District’s limits.

* * *

When John Wesley Powell died in 1902, Holmes became head of the Bureau of American Ethnology. And after 1902, Holmes spent much of the rest of his career defending his archaeological work. The Bureau also struggled to define itself after Powell’s death. Several notable Washington scientists, including ethnologist W.J. McGee of the Bureau and even Alexander Graham Bell, wanted to see it become a source of applied science for race issues in the country. But others, such as the Secretary of the Smithsonian Samuel P. Langley, frowned upon such a use of government science.[15]

But under Holmes’s directorship, the Bureau became a strong supporter of government preservation of antiquities, especially as it turned its attention to the Caribbean and the Pacific. As D.C. grew rapidly in the early twentieth century, Holmes also looked to preserve Piney Branch. Expanding the city along 14th and 16th Streets, builders and developers started to pollute the Rock Creek tributary not long after Holmes’s archaeological work. In his twenty-volume scrapbook of his life called Random Records of a Lifetime in Art and Science, Holmes dedicated many pages to the history of the preservation of Piney Branch. He included newspaper articles with interviews he had done with the press and letters he sent in 1925 to Colonel Clarence Sherrill, who was director of the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital at the time.[16] By 1926, the Evening Star reported that a serious movement had gained traction to preserve Piney Branch and the quarry as a park, backed by Smithsonian scientists. The Evening Star feared that the site was at risk of “complete obliteration by modern building operations.”[17]

Holmes led this charge. He told Sherrill that “to me this old quarry in the center of the capital city of the nation is a sacred spot.”[18] In his interview with the Evening Star reporter, Holmes argued that Piney Branch ought to be preserved for both its romantic beauty and its historical and scientific importance. He wished it to be intact for future generations of Americans, a desire, the Evening Star noted, that remained very close to his heart. The Evening Star reprinted Holmes’s call to action that he had sent to Sherrill in a letter the year before:

A most serious question thus presents itself to our people. Shall we go on selling and buying and selling again the hills and valleys of their birthright, amassing fortunes upon fortunes, without a thought of their former existence or their sacrifice? In the world’s history races have succeeded races in the possession of the garden spots of the world, and are we to follow the example of the barbarians of the past? Or shall we preserve this Piney Branch site, erecting thereon a monument, a memorial, to show the world that we are not utter ingrates?[19]

As noble as it sounds, the passage obscures many of Holmes’s true intentions. As historian David J. Meltzer has pointed out about Holmes’s autobiographical collection, “Random Records hides more than it reveals.”[20] In creating his scrapbook on his life, Holmes discarded many letters but kept ones that were complimentary. His twenty-volume collection was itself an act of self-preservation, and the preservation of Piney Branch was part of this same project. It was a tribute to his science, and a tribute to his life. Less a tribute to the Nacotchtank people and culture that he viewed had been stuck in the cultural evolutionary stratum of the past. In his letter to Sherill in 1925, Holmes made sure to convey that, “my discoveries there have done more to clear up the story of man in America than any single piece of research within the United States.” The “ruthless invaders,” as Holmes called urban developers, were those who contributed to the erosion of his own legacy.[21]

* * *

[First person reflection on trip to Piney Branch Park]

Neither the city nor the federal government ever erected a monument on the site, and it is likely that not many Washingtonians would know what you were talking about if you asked them about the Piney Branch quarry. A couple of recent articles from The Washington Post have mentioned the Piney Branch quarry, but the site remains a small footnote within the larger historical textbook that is D.C.[22]

But the complicated history of Piney Branch reveals something about preservation, especially of an urban site that is folded into the day-to-day lives of thousands of people. Preservation means something different to different people, and its meanings change over time. Today, many see Piney Branch simply as a green space, and possibly some know of its quarry. Even fewer would know of Holmes and the work he put into preserving the park for his own legacy. For Washingtonians of the early and mid-twentieth century, Piney Branch and the Native American past it represented framed the contemporary urban development and growth in larger historical narratives of progress and modernity. Preserving the Piney Branch site in 1928 was, in part, an act of preserving a belief in a certain historical inevitability. This vision of Piney Branch is now decades behind us, and it has become part of its historical, geological strata. Maybe now, if you decide to take a stroll at Piney Branch one day, you will uncover all the memories embedded in the layers of its earth.

Works Cited

Asch, Chris Myers and Musgrove, George Derek. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Baker, Lee D. From Savage to Negro: Anthropology and the Construction of Race, 1896-1954. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

“Describes Prehistoric Record Left in Rocks of Washington.” Evening Star. April 5, 1924.

Hedgpeth, Dana. “A Native American tribe once called D.C. home. It’s had no living members for centuries.” The Washington Post. November 22, 2018.

Hinsley, Curtis. Savages and Scientists: The Smithsonian Institution and the Development of American Anthropology, 1846-1910. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981.

“Historic Valley Plans Prepared: Piney Branch’s Glamourous History Recalled in Development Project.” Evening Star. June 9, 1930.

Holmes, W. H. “A Quarry Workshop of the Flaked-Stones Implement Makers in the District of Columbia.” American Anthropologist 3 (1890): 1-26.

––––––. “ Modern quarry refuse and the Palaeolithic theory,” Science 20 (1892): 295-297;

––––––. “Gravel man and Palaeolithic culture; a preliminary word.” Science 21 (1893): 29-30.

––––––. “Are there traces of man in the Trenton Gravels.” Journal of Geology 1 (1893): 15-37.

––––––. Random Records of a Lifetime in Art and Science. National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Washington, D.C.

“Indians Had Implements Shops Here, Smithsonian Scientist Discovers.” Evening Star. March 21, 1926.

Kelly, John. “D.C.’s Quarry Road once led to a quarry. It once was home to the zoo’s bears, too.” The Washington Post. December 12, 2019.

Love, Philip H. “Indians in ‘Quonset’ Huts.” Evening Star. October 24, 1948.

Meltzer, David J. The Great Paleolithic War: How Science Forged an Understanding of America’s Ice Age Past. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

“Old Flint Quarry Should Be Marked Col. Grant Avers.” Evening Star. October 22, 1929.

Runnels, Curtis. “The Piney Branch site (District of Columbia, U.S.A.) and the significance of the quarry-refuse model for the interpretation of lithics sites.” Journal of Lithic Studies 7 (2020): 1-17.

“Science Uncovers Capital’s Indian Background.” Evening Star. October 13, 1935.

“‘Widow’s Mite’ Legend Treasured Chapter in D.C. Indian Lore.” Evening Star. March 18, 1928.

[1] David J. Meltzer, The Great Paleolithic War: How Science Forged an Understanding of America’s Ice Age Past (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). See also Curtis Runnels, “The Piney Branch site (District of Columbia, U.S.A.) and the significance of the quarry-refuse model for the interpretation of lithics sites,” Journal of Lithic Studies 7 (2020): 1-17.

[2] Curtis Hinsley, Savages and Scientists: The Smithsonian Institution and the Development of American Anthropology, 1846-1910 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981), 100-101.

[3] Ibid., 100-105 and Lee D. Baker, From Savage to Negro: Anthropology and the Construction of Race, 1896-1954 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 26-53.

[4] Hinsley, Savages and Scientists, 104-105.

[5] Meltzer, The Great Paleolithic War, 472-473.

[6] Meltzer, The Great Paleolithic War, 3-4

[7] Ibid., 4.

[8] W.H. Holmes, “A Quarry Workshop of the Flaked-Stones Implement Makers in the District of Columbia,” American Anthropologist 3 (1890): 2. See also Holmes’s additional papers: W.H. Holmes, “ Modern quarry refuse and the Palaeolithic theory,” Science 20 (1892): 295-297; W.H. Holmes, “Gravel man and Palaeolithic culture; a preliminary word,” Science 21 (1893): 29-30; W.H. Holmes, “Are there traces of man in the Trenton Gravels,” Journal of Geology 1 (1893): 15-37.

[9] Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove, Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 227.

[10] “‘Widow’s Mite’ Legend Treasured Chapter in D.C. Indian Lore,” Evening Star, March 18, 1928 and “Old Flint Quarry Should Be Marked Col. Grant Avers.,” Evening Star, October 22, 1929.

[11] “Historic Valley Plans Prepared: Piney Branch’s Glamourous History Recalled in Development Project,” Evening Star, June 9, 1930.

[12] “Describes Prehistoric Record Left in Rocks of Washington,” Evening Star, April 5, 1924.

[13] “Science Uncovers Capital’s Indian Background,” Evening Star, October 13, 1935.

[14] See also Philip H. Love, “Indians in ‘Quonset’ Huts,” Evening Star, October 24, 1948.

[15] Hinsley, Savages and Scientists, 275-280.

[16] William Henry Holmes, Random Records of a Lifetime in Art and Science, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

[17] “Indians Had Implements Shops Here, Smithsonian Scientist Discovers,” Evening Star, March 21, 1926.

[18] William Henry Holmes, Random Records of a Lifetime in Art and Science, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

[19] Ibid., and “Indians Had Implements Shops Here, Smithsonian Scientist Discovers,” Evening Star, March 21, 1926.

[20] Meltzer, The Great Paleolithic War, 577.

[21] William Henry Holmes, Random Records of a Lifetime in Art and Science, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

[22] John Kelly, “D.C.’s Quarry Road once led to a quarry. It once was home to the zoo’s bears, too,” The Washington Post, December 12, 2019 and Dana Hedgpeth, “A Native American tribe once called D.C. home. It’s had no living members for centuries.,” The Washington Post, November 22, 2018.