Killing Sparrows to Grow:

Developing State Policies Scientific in Form, Maoist in Content

Script:

Imagine, for a moment, that you are once again six years old, and back in grade school. One sunny morning, as birds chirp in the trees, you and your classmates are called out into the schoolyard. An adult, someone very important in the school’s administration, quiets you all down and starts to talk. The loudspeakers set up in the schoolyard carry his voice far beyond the school and into neighboring homes. “There are millions of starving people in this world,” he says, “people who do not have enough food and so are hungry. Some of them even live here in our country. Is it not our job to help them?” Like any well-meaning six-year-old, you think about this for a second, and then agree. Your classmates nod with you. The adult points to a group of tiny birds hopping up and down as they pick through a pile of sunflower seed bits that someone had spat onto the ground. “One reason people are so hungry,” he says, “is that sparrows eat millions of tons of grain each year, grain that could feed our hungry people. It is our duty to obliterate these food thieves from the country.” Three days later, you are part of a gleeful parade. The entire community is out in force. You and your classmates are at the front of this parade, at the very vanguard of the group; you lead them from tree to tree as you march on and on. Your neighbors – the butcher, some farmers, the milk seller and a gaggle of old aunties – all clap, yell, scream, bang pots and pans, and throw firecrackers into the air. Ahead of you is a great cloud of sparrows, terrified by the commotion. You are herding them with your sounds and shouts, and the odd slingshot pellet… This goes on for six hours until the tiny birds, obviously exhausted, some even frightened into cardiac arrest, begin to drop from the sky and fall to the ground where they are trampled and seized. You are surrounded by sparrows, dead and dying; explosions and clanging vibrate the air as your friends and neighbors merrily scoop the limp creatures into baskets.[1]

Of course, this is difficult to imagine. But this was a very real experience for millions of youths who grew up in mainland China in the late 1950s. The above scenario is a paraphrased episode from the memoirs of engineer and business professor Sheldon Lou, who grew up in revolutionary China, before emigrating to the US later in life. In one chapter, Lou recounts the moment when he first learned, in 1958, that Mao Tsetung, leader of the Chinese Community Party and founder of the People’s Republic of China, had declared a war on sparrows.[2]

Mao’s war on sparrows, colloquially known as the Smash Sparrow campaign, represented one of the first projects of true mass mobilization in the nascent PRC’s history. Mao himself had declared sparrows to be a national pest, and decreed on 18 May 1958 that “the whole people, including five-year old children, must be mobilized to eliminate [sparrows].”[3] The country rose to the occasion, and by 1959, uncountable millions of sparrows had been slaughtered. By the end of 1958, however, Chinese farmers were noticing an unintended consequence: a marked spike in locusts and other insect populations. By 1959, the oddity had escalated into crisis, as tsunamis of locusts devastated crop yields, triggering what has come to be known as the Great Famine. At least 45 million people perished as a result of the famine, which stretched from 1959 to 1962.[4] It would be disingenuous to say that the Smash Sparrow campaign was the only cause of the famine. But it was certainly a leading one.[5]

How had this happened? Was it so easily forgotten that sparrows ate insects? Had it really never before been known that sparrows were farmers’ allies in pest control? There is no one single person to blame (although Mao certainly does deserve a lion’s share). Rather, to understand how this disastrous decision and famine came to be, we need to understand the systems of scientific knowledge and power that Mao had set in place that in turn allowed such poor ecological choices to be made. The earliest years of Mao’s nascent revolutionary state were defined by his and his Party’s distrust of China’s intellectuals. In the mid-1950s, realizing once and for all that he needed ‘science’ on his side, Mao engineered a rapprochement with these intellectuals, many of whom were natural scientists. He enlisted them to draft a great Twelve-Year Plan for the country’s development – a map forward based in science. For Mao believed that: “For the purpose of attaining freedom in society, man must use social science to understand and change society and carry out social revolution. For the purpose of attaining freedom in the world of nature, man must use natural science to understand, conquer, and change nature and then attain freedom from nature.” Freedom – utopia – was only to be obtained once both society and nature had been fundamentally altered, even tamed, by the revolution.

At the heart of this Twelve-Year Plan was Mao’s idea that ‘Man Must Conquer Nature’ (Ren Ding Shen Tian). [6]Problems began to materialize when Mao began to implement this plan. For he understood development as a battle between human will and nature. Nature could be transformed, provided a large-enough and determined-enough labor force. Nature could be eliminated, provided a large-enough army. Mao had won the civil war by leveraging his Party’s phenomenal skills in mass mobilization to mobilize huge coalitions of the country’s disparate and varied communities in support of his utopian vision of the future.[7] It made sense, then, to Mao that mass mobilization could be the key to rapid economic development as well.

The scientists had done their part in providing a roadmap for success, couched in the language of scientific rationalism. But Mao left it to his Party cadres – generalists, not experts – to hone, coordinate, and execute the details of that Plan. One year after his Twelve-Year Plan was in place, Mao once again began to persecute China’s intellectuals. He then appropriated the Plan and made it his own, substituting mass mobilization for scientific expertise. China’s development, Mao decided, would be scientific in form, but revolutionary in content.

What does this mean? It means many of Mao’s decisions in the late 1950s and early 1960s were aesthetically scientific, but not scientifically sound. Having inherited the language and semiotics of scientific rationalism from his persecuted intellectuals, Mao used these scientific aesthetics to justify his political ideas, rather than using scientific ideas to justify his political aesthetics.[8] The result was that, in 1958, an economist, and not an ornithologist or biologist, recommended that China annihilate its sparrow population. No consideration was given to how removing sparrows from an entire country’s ecosystem might effect the intricate web of ecologies of which humans were part, and on which humans depended to survive. In believing that ‘Man Must Conquer Nature,’ Mao viewed humans as outside of, and not part of, the natural world. This belief, a unifying slogan of the largest mass-mobilization campaign in world history, ushered China into a new, horrifically vast age of self-devouring growth.[9]

This podcast follows the making of this crisis, unpacking the story in three acts. Act one gives more background to the Smash Sparrow Campaign, situating it more precisely in the context of Mao’s revolution. Act two explores the historical symbolism of birds in China, what killing sparrows meant on a poetic level, and why it was so difficult to make sparrows into villains. Act three follows the rise and fall of China’s intellectuals in the 1950s, establishing how Mao extracted the aesthetics of science from this group while simultaneously spurning their actual expertise and warnings. We end with some brief conclusions, and words on how best to contextualize this bizarre and tragic episode of world history.

Act I: Seeking Context

What exactly does it mean to say that Mao’s view of modernity – the notion that ‘Man Must Conquer Nature’ – had ushered China into a new, heightened period of self-devouring growth? ‘Self-devouring growth’ is historian and public health scholar Julie Livingston’s phrase for a set of human decisions that operate under the ideological imperative of ‘grow or die; grow or be eaten.’[10] It is a cancerous model of development that prioritizes the growth of economic and social output above all else, ignoring – even accepting – the cascade of unseen consequences.[11] The bulk of these ‘unintended consequences,’ of course, materialize in the form environmental fallout (sometimes quite literally) which then in turn has the ironic aftermath of greatly harming the very modes of productivity that were championed in the first place. And most of these consequences stem from humans’ inability to conceive of themselves as part of nature, not above or outside of it.

Livingston’s self-devouring growth was but one iteration in a long line of ideas on how humans interact with their environments, and on how human society at large views itself in relation to nature. In 1990, the self-styled radical environmentalist Christopher Manes coined the phrase ‘culture of extinction’ in a nod to industrialized humanity’s compulsion to assault key facets of the environment, blindly if not happily destroying the very environment that we rely on to survive.[12] The phrase has since gained lots of traction; philosopher Frederic Bender co-opted it for the title of a 2003 book equating the anthrogenic impact of industrial humanity with the destructive scale of the very meteorite that killed off the world’s dinosaurs. “We of the culture of extinction treat Earth as if it were an infinite sink for our pollutants and wastes,” he writes. “We divert its waters for our use, ignoring the impact elsewhere. … We prevent lighting fire from renewing forests. … Our trade and travel habits promote bioinvasion.” In short, “whenever we make large-scale changes in the ecosphere, [we inadvertently] set in motion events that can cause ecosystems to crumble without warning.”[13]That seemingly tiny human action and innovation can provoke unimaginably massive environmental consequences on the scale of a meteoric cataclysm is the result of one simple yet stubborn problem – the problem of anthropocentrism, or human chauvinism. The belief that humans are somehow outside, or otherwise superior to, nature.

This reading of cultures of extinction – that of human hubris and eco-chauvinism –has been picked up by a litany of writers and scholars since the 1990s, from literary and environmental theorist Ursula K. Heise, to Thom van Dooren who, in 2014, wrote on cultures of extinction specifically in relation to birds.[14] But for our purposes, I think Livingston’s self-devouring growth actually provides a much more evocative and appropriate framework for thinking about Mao’s China. For it sounds less like a death cult, and better describes the tragic (and ironic) consequences of lofty utopian ambitions.

It is important to remember, after all, that Mao had come to power preaching a vision of a utopian socialist future in which science and rationalism reigned, and cleanliness and hygiene were the norm.[15] This was the context in which the Smash Sparrow campaign came into existence – a plan for bettering Chinese society’s hygiene, health, and food. The Smash Sparrow campaign was part of a larger public health effort known as the Four Pests Campaign, a mass-mobilization project designed to rally the entire country in a collective undertaking to eliminate four common household pests: the mosquito, the housefly, the rat, and the sparrow. Smash Sparrow and the Four Pests Campaign in general were all initiatives of Mao’s Great Leap Forward – a collection of projects and programs designed to shock China’s society and economy into a state of rapid development. [16] The Great Leap Forward, initiated in May 1958, was Mao’s answer to the question of what could happen if every single citizen was conscripted into a socioeconomic revolution overnight.[17] Not even the Soviet Union’s famous Five-Year Plans were that ambitious. Aims of the different Leap programs ranged from exponentially increasing crop yields, to (rather infamously) creating a network of backyard iron smelters, to the (actually quite successful) barefoot doctor campaign, which promised medical attention for every rural village (and laid the groundwork for one of the most ambitious mass-vaccination drives in history).[18] Although they cut across a wide range of sectors, from public health to heavy industry, all Leap initiatives were united under Mao’s idea that, by working together, China’s population could collectively conquer nature, putting utopia that much more within reach.

Why did this appeal so much to people that they were willing to kill millions of birds? China had been frozen in a constant state of warfare from 1927 to 1949 (including the Japanese invasion of China, the ensuing Second World War, and the Chinese Civil War). An unending spate of violence for two straight decades had upended lives and livelihoods, decimating China’s society, economy, and environments. The Leap offered more than a return to stability – Mao promised that a revolutionary transformation was about to take place. Again, Mao preached a vision of a utopian socialist future in which science and rationalism reigned, and cleanliness and hygiene were the norm.[19] The first step of that transformation was to catch up with the rest of the world in terms of agriculture, industry, and productivity. It was a massive task, of course. But Mao believed it could be done – he had an army in the country’s unified labor force. So this was just another battle than needed winning.

And nowhere was this battle more visceral than in Mao’s war on sparrows. While most of Mao’s other plans for development hinged on overwhelming the powers of nature to change it, the Four Pests Campaign was entirely annihilationist in its aim. Rats, mosquitoes, and houseflies we might understand – they had long best connected to problems of hygiene and health.[20] But how did sparrows become a pest?

In 1958, state economists, fretting over China’s perpetual food shortage – still felt a full decade after the wars – declared common house sparrows to be pests. These economists had somehow calculated that a single sparrow consumed roughly 4.5 kilograms of grain per year – grain that would otherwise go to feeding humans. It was then calculated that for every million sparrows killed, China could wrest back from nature enough grain to feed an extra 60,000 people per annum.[21] Everyone – from the youngest children to the old and infirm – was drafted into the Smash Sparrow campaign. Adults would spread poison and destroy nests, the elderly would bang pots and pans to keep sparrows from landing, and kids and teenagers would kill them with slingshots and firecrackers.[22] The campaign was inaugurated in Beijing, and within three days over 800,000 sparrows had been killed in the city alone.[23] As the campaign swept across the country, village after village organized holidays in which all hands turned out to kill sparrows for a day or two. The campaign wore on for over a year; the killing of sparrows became both a daily occurrence and a common pastime of children – the activity is featured in countless works of memoir and fiction set in the late 1950s.[24]

No one knows exactly how many sparrows were killed in that year, or the next. Estimates are in the millions, if not more. What is clearer, though, is what happened next: the resulting explosion in locust numbers enflamed an existing food shortage into the most terrible famine of the twentieth century – perhaps in all of history. Only in 1960 was the connection formally made between grain shortages and the sparrows. One brave scientist eventually had the courage to point out to the Party that sparrows also (and perhaps primarily) ate insects. The National Academy of Sciences soon issued reports on how many insects sparrows ate compared to how many seeds. Embarrassed, Mao famously just said, “forget it,” ending the Smash Sparrow campaign in a single dismissive word.[25] By late 1960s, Party messaging had quietly replaced sparrows with bedbugs as the fourth pest of the Four Pests Campaign. But, unwilling to publicly acknowledge their mistake, the Party never officially never officially rehabilitated sparrows. As a consequence of this, millions of people continued to kill sparrows – out of habit or sport – for years after the campaign’s quiet end. Factor into this the (rather obvious) problem that many other birds and species were caught up in China’s sparrow-killing tactics. The result was a prolonged and enduring avian devastation in China – sparrow numbers recovered very gradually, and only seemed to reach their pre-1958 numbers by the early 1980s.[26] Other, more rare species caught up in the campaign never recovered.[27]

We do not know much more about the Sparrow Campaign. The Party never kept records of their blunder. In fact, not much was known about the Great Famine, either, as most government figures and reports were similarly not reliable.[28] It was only in the early 2000s that Frank Dikotter and Zhou Xun excavated new information on the famine, bringing entirely new dimensions to the famine’s scale.[29] Since the 1960s, scholars have blamed the famine, which killed 45 million people, on Mao’s aggressive collectivization campaigns. Only with Dikotter and Zhou’s work, along with political ecologist Judith Shapiro’s work, have historians been able to prove what fiction writers and artists have known for decades: Mao’s sparrow campaign turned utopian aspirations, tinged with vanity, into ecological collapse.[30] The famine had its roots not solely in the political realm – the mismanagement of collective farms or grain supplies – but in the ecological – the unintended consequences of self-devouring growth.

Act II: The Historical Role of Birds in Chinese Cultures[31]

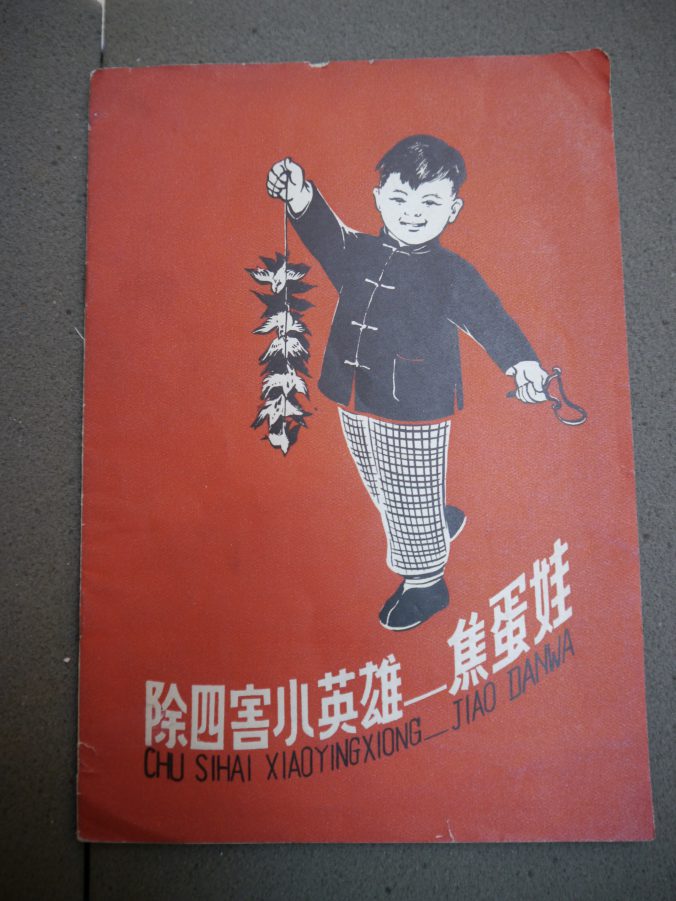

Sparrows were not always pests in China. They had long evolved to live alongside humans in settlements and cities, and represented one of the most visible connections to nature.[32] Perhaps one of the strangest aspects of this story was the abruptness of sparrows’ villanization in Chinese society, and the distinct lack of cultural follow-through, at least from an outside observer’s perspective. For one cannot help but notice that the countless propaganda images drawn to accompany and amplify the state’s villainization of sparrows, never made them out to seem all that villainous. In fact, the sparrows, whether depicted flying overhead or ‘criminally’ eating grain, trapped under baskets or skewered by a dagger, were always drawn to be cute, or at the very least in a neutral style. They were never drawn as rotund creatures, fattened up on people’s stolen staples; never drawn as thieving animals with malicious beaks or sharp talons. Indeed, among their fellow criminals – scruffy-looking rats, bloodsucking mosquitoes, and offputtingly hairy houseflies – the sparrows often looked downright cute in comparison.

For, far from pests, sparrows had, for centuries, been considered to be auspicious creatures, if not semi-deities. Given the backdrop of Western scholarship’s historical legacy of orientalism, one hesitates to draw too much inference from ancient of medieval customs when seeking to understand modern phenomena. It hardly needs to be said that revolutionary China of the 1950s was a fundamentally different space and society from any of the polities that came before it. However, we can still note that, throughout most of China’s dominant cultures, birds have historically occupied an honored and special role in Chinese mythology and society, symbolizing communication between gods and humans, and representing a physical connection between heaven and earth.

Ruling from 1600 to 1046 BCE, the Shang dynasty is regarded as among the first ruling dynasties to be verified by historical record. According to archeologists such as Herrlee Creel and anthropologists such as Florance Waterbury, the Shang dynasty was an amalgamation of two earlier Neolithic communities: the northern Tungus Tribe, and the so-called Black Pottery People.[33] Some of the earliest-dated Neolithic animal-images ever to be found in China were drawn on pottery attributed to the Black Pottery People. What makes these animal-images so interesting is that, time and again, they only featured one living creature – a crestless bird with bulging eyes and downward curved beak “whose head typically appears on vessel covers as a knob or handle.[34] Later Shang dynasty pottery, on the other hand, typically depicted two animals – the familiar bird, and an additional tiger (or sometimes leopard). Creel and Waterbury have both connected these two animals to the legend of the Hsi Wang Mu, the Queen Mother of the West, a connection that more recent scholars such as historian Susan Cahill have since corroborated. The earliest references to Hsi Wang Mu that scholars have found date back to oracle bones inscribed with her legend in the fifteenth century BCE, predating even Taoism. But eventually the goddess was incorporated into the medieval Taoist pantheon of the immortals, which helped to standardize and spread her myth. She eventually became worshipped as the greatest goddess of the T’ang dynasty (618-907).[35]Always associated with mountains and the west (ie modern Yunnan and Sichuan) Hsi Wang Mu was often depicted as a human woman with a leopard’s tail, tiger’s teeth, and tangled hair decorated with a tall jade comb. Although she lived in a cave, she was still a queen, and so was attended by servants – three great birds. In some descriptions or depictions, these birds were green, other times, blue, or even white. Sometimes there were three birds, other times only one, or one large bird with three legs.[36] But what is important here is the proximity of these birds to Hsi Wang Mu. They inhabited the sun, living not quite in heaven but not quite on earth. And yet they brought Hsi Wang Mu her food, and did her bidding, often appearing to humans as the goddess’ messengers and agents. Indeed, many T’ang-era poems associate birds with Hsi Wang Mu’s messengers, and so play on the theme of communication and separation between the human and divine realms. Because birds link heaven and earth, their appearance is always lucky or auspicious. We see this in countless T’ang works by poets like Wei Ying-wu and Li Shang-yin, but especially Li Po (701-62). Birds are everywhere in Li Po’s collections, but their role is made most clear in a poem celebrating his ascent of a sacred mountain (Mount T’ai) in 742. He describes his hike as a pilgrimage to Hsi Wang Mu’s plane of existence. He knows that he is on the right path when he encounters two birds dancing – a feng and luan, loosely translated perhaps as a phoenix and simurgh.[37] For Li Po, these two birds signify the point when he transitions from earth to heaven. According to Cahill, Li Po’s work helped to solidify the role of birds – half earthly and half divine – as enduring natural symbols of communication between gods and humans throughout the centuries.[38] In fact, in T’ang-era Taoist tradition, a person who had risen to transcendence was termed a “feathered person” in recognition of their birdlike ability to fly – for at the end of mortal life, “the transcendent was believed to ‘ascend to heaven in broad daylight.’”[39]

Return, for a moment, to Mao’s favorite slogan: ‘Man Must Conquer Nature’ (Ren Ding Shen Tian). According to one of Shapiro’s informants, a Yunnanese botanist who lived through the Leap, Mao liked this phrase because it stood in revolutionary opposition to what he perceived as an outmoded traditionalist philosophy of moderation in extraction and adaptation to nature, embodied in the slogan ‘Harmony between the Heavens and Humankind’ (Tian Ren Heyi).[40] If we are afforded the liberty of equating the heavenly with nature, and the earthly with humankind (not a wild abstraction given many of the themes in Li Po’s works), then we can understand birds, in ancient and medieval Chinese traditions, as representatives of the bridge between man and nature (in lieu of heaven). How sad, then, but poetically fitting, that Mao’s endeavor to disturb this balance of the natural order, to conquer nature once and for all, involved the slaughter of the very symbol of man’s harmony with nature. Mao rejected his ties to the natural order, instead viewing himself outside of it.

Act III: Socialist Modernity and Battling Against Nature

This notion of humankind as outside or above nature was a central theme of Mao’s grasp of science, but also of almost all science at the time. The historian Laurence Schneider opens his study on Lysenkoism in China with the following assertion: “Understanding nature has seldom been entertained as an end in itself in modern China. Science has been thought of as an instrumentality, and controlling and transforming nature its assigned goal.”[41] Without a doubt, science in Maoist China was all about control — humankind’s ability to control, shape, and tame nature. However, it is critical to point out that this conception of science as instrumentality was not unique to Maoist China. In fact, it was precisely because other states and societies had made these connections and advancements that Mao’s China could ‘leapfrog’ and make such great, sweeping, experiments in controlling nature so quickly and with such great effect.

Although the ‘scientific’ aspects of Marxism are endlessly repeated, exalted, and probed, socialist modernity has, by no means, a monopoly on the link between technology and utopia. Long before the ‘specter of communism’ rose over Europe, technology was understood as a mode of liberation for its ability to save labor. It was identified as key to the ideation and realization of utopias by a wide range of thinkers: some socialist and some very far afield from Marxian projects.[42] On a similar note, the idea of planning has also never been exclusive to socialist modernity. Planned science — and, indeed, the science of planning — had been central to a vibrant transnational scientific debate for most of the 1930s, with first the Soviet Union and Great Britain, and later, Germany, the United States, and Japan becoming proponents of large-scale state-planning initiatives in areas of science and technology. Indeed, the Second World War tested, and then the Cold War proved, that centrally-planned science (later known as ‘Big Science’) need not be the exclusive domain of centrally-planned economies — it could and did feature prominently into Anglo-American modes of liberal capitalism.[43] (It was precisely because planning lay at the heart of both capitalist and socialist modernities that the Global South’s Cold War-era brinksmanship in aid was able to take shape as it did, essentially an East/West battle over the privilege to help plan, fund, and execute a slew of long-term development projects across the Global South.)[44]

This is all to say that by the time Mao established the People’s Republic of China in 1949, understanding science technology as key to establishing utopia, and viewing centrally planned science as a viable path to get there, was not a particularly new or revolutionary stance. But it was precisely because of this — because so many other states and modernity projects had experimented with technological development and central planning — that Mao’s PRC was able to hit the ground running.[45]

And hit the ground running, it did. When Mao’s Chinese Communist Party (CCP) finally won China’s civil war and took over the surviving state apparatuses, they inherited a robust national system for scientific research already fine-tuned for central planning. For the Nationalist Kuomintang government had already established, in 1927, a central office to oversee all science research and funding in China – the Academia Sinica. Tehnically speaking, after the civil war’s end in 1949, the headquarters of Academia Sinica was relocated with the Nationalist government to the island of Taiwan. But this was largely a symbolic move. The Nationalist evacuation was difficult enough just moving people and gold, and so the vast majority of Academia Sinica’s institutes, infrastructure, and equipment stayed on the mainland to be absorbed into Mao’s PRC. A large percentage of Academia Sinica’s scientist community, unwilling to part with their research, and already ideologically sympathetic to leftist ideas and eager for greater science planning, chose to stay with their institutes.[46] In other words, Mao’s new communist state had, right off the bat, inherited an entire community of scientific elites who oversaw an advanced network of research institutes and infrastructure. This inheritance was quickly fashioned into the new Chinese Academy of Sciences, which was officially established just one month after the birth of the PRC.[47]

To have such sophisticated research networks already in place upon founding a high modern state was a great luxury – something the Bolsheviks could only have dreamed of. It was a great irony, then, that Mao was loath to accommodate these scientists, the vast bulk of whom had been educated in the West, and so were figures of political distrust for Mao. According to historian Zuoyue Wang, one clear indication of this political distrust came in the form of Mao’s tasks for the Academy of Sciences. Despite having a sophisticated and accomplished research organization at his disposal, the problems he tasked the Academy with solving were utterly mundane and often came with ideological consequences. Mao was quick to test the intellectuals’ allegiances, and did so often.[48] According to Schneider, Mao ardently believed that “a self-contained authority of a cosmopolitan science community posed a threat to the authority of Mao’s Communism.”[49] In short, while the scientists all believed that simply by doing science they were contributing to national progress, Mao saw only that their commitment to science and technical issues excluded commitment to social revolution — as he defined it.”[50]

This class struggle — Mao’s circle versus the foreign-educated intellectuals — hampered the PRC’s technological development for the first five years of its existence. But in January 1955, Soviet soil scientist and technological advisor to Beijing V.A. Kovda suggested the implementation of various central planning initiatives.[51] Mao’s trust in his Soviet science advisors was strong, and because central planning needed planners, the Party reconciled with the scientists.[52] In January 1956, the CCP Central Committee declared its goal of catching up to global leaders in economic and scientific matters by issuing a call to ‘march on science.’ Scientists from a variety of fields and industries were mobilized to draft a twelve-year plan (from 1956 – 1967) that would rapidly advance China’s prowess in science and technology.[53] A heady optimism for scientific possibility and exploration was encouraged by Chairman Mao’s May 1956 speech in which he decried: “Let a hundred schools of thought contend and a hundred flowers bloom.” It sounded as though Mao was calling for unfettered scientific exploration and freedom of thought. Chinese society seemed poised on the precipice of a major scientific revolution as Mao toured the countryside promoting these freedoms – along with the people’s right to openly question and criticize the party – in a celebration of social unity that became known as the Hundred Flowers Campaign.[54]

Under the auspices of Mao’s Hundred Flowers, late 1956 saw a flurry of scientific and artistic publications carrying bold predictions for China’s path to future socialist modernity. These publications, often written in the language of scientific Marxism, represented the scientific community’s response to this rapprochement with the Party, and extolled the virtues of CCP-led science, distilling and highlighting key aspects of the 12-Year Science Plan. Xu Liangying and Fan Dainian’s Science and Socialist Construction in China is often used in Western scholarship as an example of such publications, not least because it was made accessible to English-speakers thanks to a US National Academy of Sciences project that funded its translation in 1982.

Unlike some of their foreign-educated colleagues, both Xu and Fan had graduated from Chinese universities before Mao had established the PRC in 1949. Both Xu and Fan were editors at revolutionary China’s leading scientific journal, Kexue tongbao (aka Scientia Sinica), (re)founded in Peking in 1952.[55] Both were tapped to help draft the CCP’s twelve-year plan for scientific advancement in 1956. They wrote Science and Socialist Construction in China together to expand on their ideas, couching them in a sober evaluation of pre-revolutionary China’s meager technological prowess, and celebrating the PRC’s willingness to invest heavily in planning.[56]

The point of the book, aside from Party flattery, was to ensure that Party and CAS messaging remained unified and loud. The central thesis of Science and Socialist Construction in China is to show control over the environment. Using science to conquer nature was the one theme on which scientists and Mao could come together — it was their shared language of modernity and belief in utopian principles, where their definitions of social revolution overlapped. [57]

The Twelve-Year Plan and publications like Xu and Fan’s book represented a syncretic relationship between the Party and China’s scientific community. The Party had welcomed intellectuals under its wing, and in return, scientists had given the Party a toolkit of scientific language and planning which it could use to ‘rationally’ justify its future policies. It was in this language that the Great Leap Forward was couched and planned.[58]

In early 1957, mere months after the Plan was finalized and Xu and Fan’s book was published, the Party enacted a new anti-Rightist campaign that targeted countless supporters of the Hundred Flowers for persecution. Chief among them were China’s scientific community. If Mao’s view of science was instrumentalist, so was his view of scientists themselves. Stripped once again of their political privileges, most natural science experts were not allowed to execute the plans they had helped create.[59] With plan in place, the battle over nature would be waged by loyal Party generalists, not specialists. This created a vast knowledge deficit – like in the case of the sparrows. The Smash Sparrow campaign was designed with the aesthetics of science in mind – economists ‘rationally’ figured that because sparrows and people both eat grain, fewer sparrows would mean more grain for people. Biologists existed at the time in China, who could have predicted the disastrous consequences of removing sparrows from the country’s ecological system. But they were not consulted. With more than 540 million citizens, Mao needed more food for his growing country. He understood that he could beat down nature to get his way. Grow or die; grow or be eaten.[60]

Conclusions

In the early years of the Soviet experiment, the young socialist state had to contend with the global rise of nationalism as a valid and popular ideology. The vertical stratification of society into national identities cut across class distinction, openly competing with the horizontal stratification of society that transnational class-based identity emphasized. In Western Europe, French factory workers were being told – through the reinforcing norms of nationalism like newspapers – that they had more in common with French merchants, than they did with German factory workers. In the USSR, Bolshevik leaders like Lenin and Stalin hoped to harness the power of nationalism instead of fighting it, by preemptively injecting nationalism into the socialist project on their own terms. In this way, the rollout of nationalism across the USSR was tempered and controlled by the state. The national cultures that emerged under state planning were engineered to such specifics that Iosef Stalin famously and repeatedly defined them as “national in form, socialist in content.” [61] The socialist project had successfully co-opted its ideological antithesis. And while Stalin was specifically describing Soviet nationalities policy, his formula of ‘X in form, socialist in content’ stands out as an incredibly useful tool of analysis for understanding other state co-options of structures seemingly outside of its control. One wonders, for instance, if it would be fair to call Mao’s sparrow economics an instance of research that was scientific in form, Maoist in content.[62]

At the very least, it seems to me that this question of aesthetics – this distinction between scientific in form and scientific in content – is among the most useful entries into a discussion about Mao’s war on sparrows. There is no question that the sparrow war and famine implicate Mao in a massive scandal of criminal negligence. But of the already scant literature that focuses specifically on the Smash Sparrow campaign, too much of it is caught up in Cold Warrior parables of Maoist atrocity and anticommunism.[63] As far as tales of self-devouring growth go, killing sparrows is a particularly poignant and bizarre example of human chauvinism its unintended consequences. But as Livingston would quickly tell us, self-devouring growth is not limited to Maoist China, or the socialist world. It is present wherever there are humans with the urge to extract at scale. For though our impacts may be outsized, we are not ‘outside’ of nature. Whether we call it environment, ecologies, ecosphere, or something else, we are part of a vast dynamic system that evolves along with us, responds to us, is driven by us, and yet drives us.[64]

Over centuries, the Eurasian tree sparrow (Passer montanus) evolved to live alongside people in China, preferring urban or settled environments to rural.[65] The tiny birds, chestnut-crowned and white-cheeked, were visible reminders of humanity’s situation inside broader ecologies. After decades of war, the Great Leap Forward was supposed to represent the advancement of peace and progress. In fact, that is when a much deeper and broader war began. China’s war on sparrows constituted a war on China itself, one from which, ecologically-speaking, has yet to recover.

Unbelievably, this podcast is not sponsored by Casper mattresses. Special thanks go to Erika Milam of the Princeton University History Department, and Alex Hollinghead of the McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning at Princeton University.

Music and Sound Attribution:

Many thanks to the Young Philosopher’s Club for the free use of their song ghosts, used at:

7:41

32:20

35:29

Many thanks to Bill Vortex for the free use of their song Les Portes Du Futur, used at:

17:17

23:19

Many thanks to the BBC Sound Effects Archive for the free use of the following sounds:

House Sparrow (Passer Domesticus) – Wingbeats

Recordist: Nigel Tucker and David Tombs

Location: Asia

Habitat: Townscape

Source: Natural History Unit

Date recorded: 5th April 1985

Comedy 2 – Frantic banging and clanging – 1967 (7B, reprocessed)

Source: BBC Sound Effects

Tree Sparrow (Passer Montanus) – Flock flying off

Recordist: David Tombs

Location: Europe

Habitat: Islands

Source: Natural History Unit

Date recorded: 1 November 1976

Bang! – Fireworks, Chinese Fire Cracker

Source: BBC Sound Effects

China – Wuhan: Vegatable Market (rural area near Wuhan)

Location: Asia

Source: BBC Sound Effects

[1] Sheldon Lou, Sparrows, Bedbugs, and Body Shadows : A Memoir, Intersections (Honolulu, Hawaii) (Honolulu: University Of Hawai’i Press In Association With UCLA Asian American Studies Center, 2005), 35–42, {“http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctvvn6jq”:[“www.jstor.org”]}.

[2] Lou, 35.

[3] Judith Shapiro, Mao’s War against Nature : Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, Studies in Environment and History. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 87, {“https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511512063”:[“doi.org”]}.

[4] Frank Dikötter, Mao’s Great Famine : The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-1962, 1st U.S. ed. (New York: Walker & Co., 2010), 9.

[5] Seonghoon Kim, Belton Fleisher, and Jessica Ya Sun, “The Long-Term Health Effects of Fetal Malnutrition: Evidence from the 1959–1961 China Great Leap Forward Famine,” Health Economics 26, no. 10 (October 1, 2017): 1264–77, https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3397.

[6] Shapiro, Mao’s War against Nature : Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, 9.

[7] Kenneth Lieberthal, “The Great Leap Forward and the Split in the Yan’an Leadership 1958-1965,” in The Politics of China : Sixty Years of the People’s Republic of China, ed. Roderick MacFarquhar, Third edition. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 88, {“https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511842405”:[“doi.org”]}.

[8] Arunabh Ghosh, Making It Count: Statistics and Statecraft in the Early People’s Republic of China, Histories of Economic LIfe 10 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 5–8, https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691199214.

[9] Shapiro, Mao’s War against Nature : Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, 195.

[10] Julie Livingston, Self-Devouring Growth : A Planetary Parable as Told from Southern Africa, Critical Global Health. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 5, {“https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctv1131dbm”:[“www.jstor.org”]}.

[11] Livingston, 5.

[12] Christopher Manes, Green Rage : Radical Environmentalism and the Unmaking of Civilization, 1st ed. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1990).

[13] Frederic L. Bender, The Culture of Extinction : Toward a Philosophy of Deep Ecology (Amherst, N.Y.: Humanity Books, 2003), 16–17.

[14] Ursula K. Heise, Imagining Extinction : The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species (London: The University of Chicago Press, 2016); Thom Van Dooren, Flight Ways : Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction, Critical Perspectives on Animals. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), {“http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/van-16618”:[“www.jstor.org”]}.

[15] Shapiro, Mao’s War against Nature : Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, 86.

[16] Ralph Thaxton, Catastrophe and Contention in Rural China : Mao’s Great Leap Forward Famine and the Origins of Righteous Resistance in Da Fo Village, Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 1.

[17] Lieberthal, “The Great Leap Forward and the Split in the Yan’an Leadership 1958-1965,” 142.

[18] Comrades in Health : U.S. Health Internationalists, Abroad and at Home, Critical Issues in Health and Medicine. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2013); Xiao Yang, The Making of a Peasant Doctor (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1976); Mr. Science and Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution : Science and Technology in Modern China (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2013), {“http://covers.rowmanlittlefield.com/L/07/391/0739149741.jpg”:[“Cover image”]}.

[19] Shapiro, Mao’s War against Nature : Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, 86.

[20] Shapiro, 86.

[21] J. Denis Summers-Smith, In Search of Sparrows (London: T. & A. D. Poyser, 1992), 123.

[22] Shapiro, Mao’s War against Nature : Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, 87.

[23] Summers-Smith, In Search of Sparrows, 124.

[24] Yan Mo, Big Breasts and Wide Hips (New York: Arcade Pub, 2004); Lianke Yan, The Four Books (New York: Grove/Atlantic, Inc, 2015), {“http://princeton.lib.overdrive.com/ContentDetails.htm?ID=EC80A6E8-838B-401B-8F14-8F89AF5644EA”:[“princeton.lib.overdrive.com”]}; Loud Sparrows : Contemporary Chinese Short-Shorts, Weatherhead Books on Asia (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006).

[25] Shapiro, Mao’s War against Nature : Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, 88.

[26] Summers-Smith, In Search of Sparrows, 124.

[27] Anders Pape Møller et al., “Comparative Urbanization of Birds in China and Europe Based on Birds Associated with Trees,” Current Zoology 65, no. 6 (December 2019): 617, https://doi.org/10.1093/cz/zoz007.

[28] Xizhe Peng, “Demographic Consequences of the Great Leap Forward in China’s Provinces,” Population and Development Review 13, no. 4 (1987): 639–70, https://doi.org/10.2307/1973026; Shige Song, “Mortality Consequences of the 1959–1961 Great Leap Forward Famine in China: Debilitation, Selection, and Mortality Crossovers,” Social Science & Medicine 71, no. 3 (August 1, 2010): 551–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.034.

[29] Dikötter, Mao’s Great Famine : The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-1962; Xun Zhou, The People’s Health : Health Intervention and Delivery in Mao’s China, 1949-1983, States, People, and the History of Social Change ; 2. (Chicago: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020), {“http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=2493164”:[“search.ebscohost.com”,”Access restricted to 3 concurrent users”]}.

[30] Loud Sparrows : Contemporary Chinese Short-Shorts; Mo, Big Breasts and Wide Hips; Yan, The Four Books; Arthur Chung, Of Rats, Sparrows & Flies– : A Lifetime in China (Stockton, Calif: Heritage West Books, 1995).

[31] For more on how Han culture relates to other indigenous communities of China, see: Kevin Carrico, The Great Han : Race, Nationalism, and Tradition in China Today (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2017), {“http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1rzx5xp”:[“www.jstor.org”]}.

[32] Møller et al., “Comparative Urbanization of Birds in China and Europe Based on Birds Associated with Trees,” 617.

[33] Florance Waterbury, Bird-Deities in China, Artibus Asiae. Supplementum ; 10 (Ascona: Artibus Asiae, 1952), 74; Herrlee Glessner Creel, The Birth of China, a Study of the Formative Period of Chinese Civilization (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1937); Florance Waterbury, Early Chinese Symbols and Literature: Vestiges and Speculations, with Particular Reference to the Ritual Bronzes of the Shang Dynasty (New York City: E. Weyhe, 1942).

[34] Waterbury, Bird-Deities in China, 76.

[35] Suzanne Elizabeth Cahill, Transcendence & Divine Passion : The Queen Mother of the West in Medieval China (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University, 1993), 1.

[36] Waterbury, Bird-Deities in China, 77; Cahill, Transcendence & Divine Passion : The Queen Mother of the West in Medieval China, 92.

[37] Cahill, Transcendence & Divine Passion : The Queen Mother of the West in Medieval China, 2.

[38] Cahill, 91.

[39] Cahill, 92.

[40] Shapiro, Mao’s War against Nature : Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, 9.

[41] Laurence A. Schneider, Biology and Revolution in Twentieth-Century China (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 3.

[42] See discussion of anima and artifice in: Utopia/Dystopia : Conditions of Historical Possibility, Core Textbook (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010), {“https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400834952”:[“doi.org”]}; Howard P. Segal, Utopias : A Brief History from Ancient Writings to Virtual Communities, Wiley-Blackwell Brief Histories of Religion (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), {“http://catalogimages.wiley.com/images/db/jimages/9781405183284.jpg”:[“Cover image”]}; Howard P. Segal, Technology and Utopia (Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association, 2006), {“http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0620/2006028872.html”:[“Table of contents only”]}; Mikhail Geller, Utopia in Power : The History of the Soviet Union from 1917 to the Present, ed. A. M. (Aleksandr Moiseevich) Nekrich (New York: Summit Books, 1986); Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (S.l.: George Routledge & Sons Ltd, 1940).

[43] For more on Big Science, see: Science and Technology in the Global Cold War, Transformations (M.I.T. Press) (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2014), {“http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctt9qf6k8”:[“www.jstor.org”]}; John W. Dower, War without Mercy : Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986).

[44] David C. Engerman, The Price of Aid : The Economic Cold War in India (Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2018); Nick Cullather, “Damming Afghanistan: Modernization in a Buffer State,” The Journal of American History 89, no. 2 (2002): 512–512, https://doi.org/10.2307/3092171.

[45] Zuoyue Wang, “The Chinese Developmental State during the Cold War: The Making of the 1956 Twelve-Year Science and Technology Plan,” History and Technology 31, no. 3 (July 3, 2015): 180–205, https://doi.org/10.1080/07341512.2015.1126024; Zuoyue Wang, “Science and the State in Modern China,” Isis 98, no. 3 (2007): 558–70, https://doi.org/10.1086/521158.

[46] Wang, “The Chinese Developmental State during the Cold War: The Making of the 1956 Twelve-Year Science and Technology Plan,” 182.

[47] Wang, 182.

[48] Wang, 184.

[49] Schneider, Biology and Revolution in Twentieth-Century China, 281.

[50] Schneider, 281.

[51] Wang, “The Chinese Developmental State during the Cold War: The Making of the 1956 Twelve-Year Science and Technology Plan,” 184.

[52] Liangying Xu, Science and Socialist Construction in China (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1982). Xii.

[53] Xu. Xi.

[54] Dayton Lekner, “A Chill in Spring: Literary Exchange and Political Struggle in the Hundred Flowers and Anti-Rightist Campaigns of 1956–1958,” Modern China 45, no. 1 (June 26, 2018): 39, https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700418783280.

[55] Zhongguo ke xue yuan, “Acta Scientia Sinica,” Zhongguo Ke Xue 1, no. 1 (October 1952), //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000494862.

[56] Xu, Science and Socialist Construction in China, 31.

[57] Xu, Science and Socialist Construction in China, 4.

[58] Shapiro, Mao’s War against Nature : Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, 195.

[59] The only exception was nuclear scientists, to whom Mao gave a wide berth and freedom.

[60] Livingston, Self-Devouring Growth : A Planetary Parable as Told from Southern Africa, 5.

[61] Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire : Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939, The Wilder House Series in Politics, History, and Culture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 12.

[62] Certainly the same could be said for Lysenkoism: Svetlana A Borinskaya, Andrei I Ermolaev, and Eduard I Kolchinsky, “Lysenkoism Against Genetics: The Meeting of the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences of August 1948, Its Background, Causes, and Aftermath,” Genetics212, no. 1 (May 2019): 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.118.301413; Michael D. Gordin, “Lysenko Unemployed: Soviet Genetics after the Aftermath,” Isis 109, no. 1 (March 2018): 56–78, https://doi-org.ezproxy.princeton.edu/10.1086/696937; Kirill O. Rossianov, “Editing Nature: Joseph Stalin and the ‘New’ Soviet Biology,” Isis 84, no. 4 (1993): 728–45.

[63] Lieberthal, “The Great Leap Forward and the Split in the Yan’an Leadership 1958-1965,” 88.

[64] See, for example: Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World : On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), {“http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctvc77bcc”:[“www.jstor.org”]}; Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Friction : An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2005), {“http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctt7s1xk”:[“www.jstor.org”]}.

[65] Møller et al., “Comparative Urbanization of Birds in China and Europe Based on Birds Associated with Trees.”

Leave a Reply