Script:

Taneil: Hi! I’m Taneil and I’m currently a first year PhD student in the history program at Princeton University. Welcome to my podcast episode. This semester, I participated in a course on environmental history. Some of my favorite readings from the semester were the books and articles that we read that discussed how humans had formed connections with nonhuman aspects of the environment and how they learned lessons from it for purposes other than colonial projects or capitalist exploitation of natural resources. Books like Connie Chiang’s Nature Behind Barbed Wire and Anna Tsing’s The Mushroom at the End of the World underscored the possibilities and necessity of telling environmental histories that center on people who turned to the nonhuman environment not to further exploit it but to find temporary solace in it or even to resist the forms of precarity and violence that they were experiencing because of imperialism and capitalism.

I suppose I was most interested in these types of readings because they resonate with a research project that I have been working on this semester, and these books helped me think through some of the sources I have spent the past few months mulling over. So, for this podcast, I figured I would present a portion of this research. Specifically, I will talk about an African American woman named Sarah Mapps Douglass and how she also incorporated the natural world into her political thought and activism.

Douglass lived in Philadelphia during the nineteenth century. She was born in 1806 and died in 1882. Though she is not really a household name today, Douglass was well-known among African American communities in the Mid-Atlantic during her lifetime. She was born into a prominent family, the daughter and granddaughter of some of the most influential Black Philadelphians during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Sarah’s father was Robert Douglass, Sr., an immigrant from the West Indies.[1] In Philadelphia, he worked as a barber and amassed an estimated worth of $8,000 by the 1830s. This amount of money made his family part of the upper class of Black people in the city at the time.[2] Robert Douglass was also engaged in Black political discussions and activism in Philadelphia. Most notably, he supported the anti-colonization movement, an organized effort that many politically active African Americans living in Philadelphia took to spurn the American Colonization Society’s efforts to forcibly remove free Black people from the United States and relocate them to Africa. Robert Purvis, a fellow Black abolitionist based in Philadelphia, remembered Robert Douglass as a “sterling and inflexible friend to human rights.”[3]

Sarah was also descended from activists on her mother’s side of the family. Her maternal grandfather Cyrus Bustill was born enslaved in Burlington, New Jersey. After achieving freedom, Cyrus moved to Philadelphia in either the 1780s or 1790s. In the city, he established a lucrative baking business. Later in his life, Cyrus founded and taught at a school for Black children. In addition to his professional pursuits, he was also remembered by his descendants as having “always championed the cause of freedom and gave of his means to promote it.”[4] This commitment to helping formerly enslaved people and their descendants live out a meaningful freedom is evidenced in part by his participation in the Free African Society, one of the first formal mutual aid organizations meant to assist people of African descent.[5] Cyrus Bustill’s professional and public life was a template that several of his descendants would go on to follow in their own lives.

Grace Bustill Douglass, was Sarah Mapps Douglass’ mother and one of Cyrus Bustill’s children whose own public life adhered quite closely to his own. Grace was also an artisan; She operated a millinery in a building next door to the building where her father operated his bakery. In addition to this business, Grace also was involved in the creation of a school for African American children.[6] In a letter to the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, Sarah recalled years later that her mother and James Forten created a school around 1819 “in order that their children might be better taught than they could be in any of the schools then open to our people.”[7] Sarah was most likely referring to the seminary established by The Augustine Education Society of Pennsylvania. The organization’s constitution does note that Forten was the society’s first vice president and that Grace’s husband Robert Douglass was the group’s treasurer. No women were mentioned in the constitution, but, as Sarah remembered, it is likely that her mother was very involved in the creation of the school even though she did not have an official leadership position.[8] Grace’s name did appear on another group’s constitution though. She was one of the founding members of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, a small, interracial group of black and white women abolitionists founded in 1833. According to their constitution, the organization’s purpose was to advocate for the immediate emancipation of enslaved people as well as the elimination of the “race prejudice” that free Black people faced.[9]

With this esteemed family history bolstering her, Sarah Mapps Douglass also charted her own path, and in doing so managed to earn the admiration of members of the free Black community in her own right. For instance, in an 1859 column in a New York City-based, Black-run newspaper called the Weekly Anglo-African, one contributor sang Douglass’ praises. The columnist, who signed the article simply with their initials “J. J.,” wrote:

Mr. Editor, Permit me say a few words through your columns in regard to an estimable lady of this city. I allude to Mrs. Sarah M. Douglass. She has been known for many years among the anti-slavery people of Philadelphia as a warm-hearted, self-sacrificing, intelligent advocate of the rights of her own race. I venture to say that but few among the ranks of reform would be more generally known throughout the State at this time were it not that a strong dislike of notoriety, amounting almost to reserve, is an essential element of her character. As it is, she enjoys the friendship and respect of many, very many, prominent friends of the cause in this city.[10]

The reserved character that this article described might explain Douglass’ relative obscurity from popular historical accounts of the nineteenth-century abolition movement that she was apparently very involved in. Indeed, her private nature would also explain why she requested that her personal papers be destroyed after her death, and it would appear that her loved ones honored those wishes. Still, and perhaps contrary to her wildest imagination or desires, Sarah and the details of her remarkable life leap out in various letters and newspapers scattered across repositories in the Mid-Atlantic and New England. What you find in these archives is that during her lifetime, Douglass was treasured and beloved by free African American communities in the Mid-Atlantic region as well as by her white abolitionist allies.

However, when I first encountered Douglass in the archive, I did not know any of these things about her. I was just captivated by some drawings of plants and insects that she had done in a friendship album that belonged to Amy Matilda Cassey, another African American woman who was a part of the Black upper class in Philadelphia. Now, you’re probably asking what a friendship album even is. Friendship albums operated a bit like an early nineteenth century version of social media or a high school yearbook. The albums were usually fancy, leather-bound books with intricately designed covers. The owners of the albums would ask their friends to write notes inside of the book’s blank pages. For instance, on the opening page of Amy Cassey’s friendship album she encouraged her friends to include a tribute of any kind that would “Enrich this mental pic-nic feast.”[11]

Black women’s friendship albums were important. Friends and loved ones wrote notes and poems expressing their love and admiration for the album’s owner inside of them. Several of the albums’ pages featured illustrations of natural scenes and objects. For instance, as they turned through the pages of Cassey’s album, her friends would have seen a drawing of a butterfly with black, green, and red wings perched on top of flowering branches. Some album entries also featured illustrations of vibrantly colored flowers. All of these colorful and often highly-detailed contributions must have been especially striking to anyone who had the opportunity to peruse the albums’ pages.

Ultimately, the beautiful and loving space that Amy Matilda Cassey created with her friendship album provided a stark contrast from the Philadelphia just outside of her home. In fact, for Black people living in Philadelphia during the three decades preceding the Civil War, there was much about the city that was ugly. By the time that Sarah Mapps Douglass was born in 1806, Philadelphia was home to one of the largest communities of free Black people in the United States. The free and self-emancipated Black people who made Philadelphia their home were subjected to myriad forms of violence and indignities by white people in the city. Many of the city’s black residents were confronted with the reality that the freedom that was currently available to them in the United States was incredibly tenuous and still insufficient for living the kind of lives they hoped for. For instance, Black people who dared to occupy space in Philadelphia were called the n-word or sometimes physically attacked by white residents. Many of the city’s most infamous “race riots” that occurred during the antebellum era targeted buildings, homes, and even bodies belonging to Philadelphia’s black elite.[12] In response to these harsh realities of life in Philadelphia, some black residents chose to stay in their homes or at least to stay very near to them. For instance, one woman from an elite Black family living in Philadelphia wrote that she and her family members “never travel far from home and seldom go to public places unless quite sure that admission is free to all—therefore, we meet with none of these mortifications which might otherwise ensue.”[13]

Despite the overwhelming extent of anti-black racism in the city, Black Philadelphians created a variety of spaces and institutions that they hoped would benefit and sustain African Americans in the city.[14] African American women’s friendship albums were one of those spaces.

Black women’s friendship albums are also rare sources. Currently, there are only four friendship albums known to have belonged to Black women who lived in Philadelphia during the nineteenth century. Three of those albums were acquired by the Library Company of Philadelphia in the 1990s and the other album is stored at Howard University’s Moorland-Springarn Research Center in Washington D.C.[15]

For these reasons, the friendship albums and especially Sarah Mapps Douglass’ drawings inside of them were not really like anything else I had come across before in doing research about Black people in the nineteenth century. And so I wondered, why did she draw these images? After doing more research and reading more about Douglass, I came to understand these drawings as windows into her political thought and activism. I argue that Douglass believed that scientific knowledge about plants and natural phenomena would be beneficial for African Americans’ struggles for freedom and equality in the nineteenth century.

While many scholars who have worked with the friendship albums argue that the floral imagery in them evidence African American women’s embrace of Victorian gender norms, I take a different view.[16] I subscribe to literary scholar Britt Rusert’s contention that Douglass’ illustrations and written contributions to the friendship albums might also serve as evidence of her familiarity with natural science discourses.[17] Douglass’ style of drawing flowers in the albums’ pages supports the claim that she was familiar with the natural sciences. Whereas other contributors drew flowers as fully-bloomed bouquets in vases, most of Douglass’ images featured just one or two flowers floating on the page. Douglass’ drawings also depicted the plants in various stages of development: while a fully-bloomed flower was the central object in an image she drew, Douglass would often frame these blooms with still-budding flowers. This approach to illustrating plants is very similar to botanical drawings done by naturalists during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[18] For Douglass then, the flowers she invoked on the pages of Black women’s and girl’s friendship albums might not have served exclusively or even primarily as symbols for certain sentiments as stipulated by the Victorian woman’s language of flowers. The plants she drew and wrote about in the friendship albums might have simply represented the actual plants themselves or even nature more broadly.

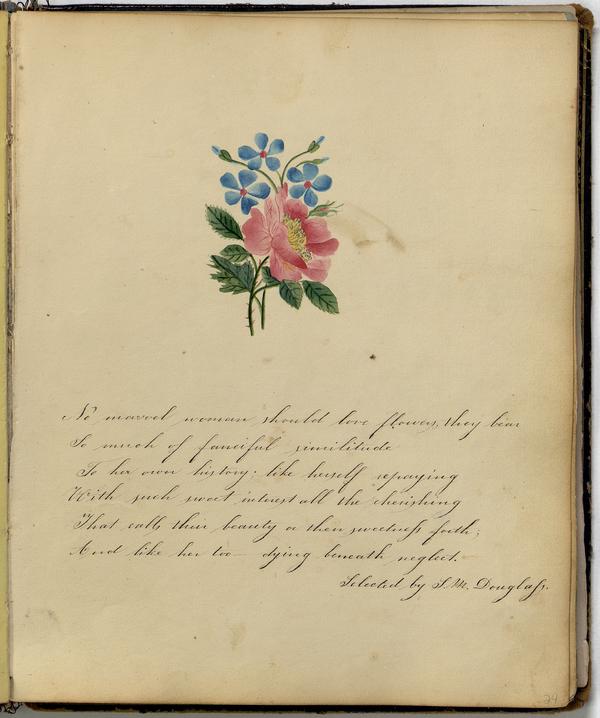

While Douglass’ illustrations of insects and flowers are what initially piqued my interests and drew me to the friendship albums, the political resonance of the poems she often included with her illustrations made me even more intrigued. I am particularly invested in an entry in which Douglass illustrated some flowers, and beneath the illustration, she neatly transcribed a poem that she likely copied from a newspaper or poetry collection. The poem read:

No marvel woman should love flowers, they bear

So much of fanciful similitude

To her own history; like herself repaying

With such sweet interest all the cherishing

That calls their beauty or their sweetness forth;

And like her too—dying beneath neglect.[19]

To me, this entry was great evidence of the way Douglass incorporated nonhuman aspects of the natural world in her political thought. I read this poem as a rare example of a written political commentary from Douglass. In it, she was critical of the treatment of plants as well as women. As I came to learn through my own research, Douglass’ life experiences beyond the pages of the friendship album suggest that her comparison of women and flowers was more than superficial or incidental and even went beyond just being a metaphor. Douglass once disclosed the nature of her relationship with flowers in a letter to a friend. She wrote “Flowers have ever been to me earnest, solemn holy teachers.”[20] Douglass believed that flowers had more to offer people than just their aesthetic beauty. And that the same was true about women.

Douglass lived during a time when, Black men and women frequently and intensely debated the propriety of having African American women be public figures and political commentators. [21] We can even see these tensions within the friendship albums. For instance, while Douglass’ poetry selection problematized women’s duty to provide others with just their “beauty and sweetness,” elsewhere in the friendship album, other Black women and men added poems that described and praised women’s duties as wives and mothers.[22] In perhaps the most extreme example that can be found on the pages of Amy Cassey’s friendship album, another Black woman named Mary Forten encouraged the women who read the album to be “good wives” who “Speak but when they are spoken to;/But not like echoes most absurd/Have forever the last word.”[23]

Forten’s poem demonstrates how some African American women “understood and reinforced their own social subjugation,” as historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar has put it.[24] Contrary to the views of womanhood that Forten put forward in her poem, the poem that Douglass chose to include in the album indicted the treatment of women as primarily or purely decorative and aesthetic figures. Instead, through the poem’s language, Douglass made the bold and contentious argument that women could offer more than beauty and sweetness as wives and mothers and thrive while doing it.

The poem that Douglass included in the album serves as just one example of her dissatisfaction with some of the gender norms and expectations of her time. In her more personal affairs, Douglass did not seem to prioritize fulfilling one of the most important aspects of respectable womanhood, which was becoming a wife. Douglass once received a letter from her friend and fellow abolitionist Sarah Grimké in which Grimké implored Sarah Douglass not to be “displeased” with her husband-to-be Reverend William Douglass. Grimké encouraged Sarah Douglass to “wear…the bridal robes of cheerfulness, yea of pleasant mirthfulness, & you will find it diffuses a charm over your own life & over all around you.”[25] Sarah Mapps Douglass must have taken her friends advice, since she did eventually marry William on July 23, 1855 when she was 49 years old. The marriage lasted just six years, ending with William Douglass’ death in 1861. Other letters between Sarah Douglass and Sarah Grimké show that Douglass seemed to have grown to enjoy William as a person, but she never seemed to come around to enjoy her role as a wife. She once referred to her marriage as “that School of bitter discipline.”[26]

Douglass was also frustrated by the way that her particular experience of sexism and racism as a Black woman thwarted her educational ambitions. Douglass was likely the author of a letter that Sarah Grimké’s sister Angelina cited in a pamphlet she wrote describing racism in the northern United States for white women who lived there in the hopes of getting them to support abolition and the elimination of racism. Angelina Grimké reported how the black woman who was probably Douglass expressed a desire for a formal education in science. But prejudice significantly hindered her ability to receive it. The letter’s author wrote:

For the last three years of my life, I can truly say, my soul has hungered and thirsted after knowledge, and I have looked to the right hand and to the left, but there was none to give me food. Prejudice has strictly guarded every avenue to science and cruelly repulsed all my efforts to gain admittance to her presence.[27]

Douglass was not continuously constrained by gender expectations that she did not want to live up to for all of her life though. Significantly, Douglass’ luck in obtaining scientific training changed in 1852 when she enrolled in the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania that had opened just two years earlier in 1850. At 46 years old, Douglass finally got a chance to obtain the type of education she had wanted for a long time. She was the first African American student at the school. The Female Medical College’s curriculum for the 1852-1853 school year included seven courses—Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children, Anatomy, Practice of Medicine, Chemistry and Toxicology, Physiology and Medical Jurisprudence, Surgery, and Materia Medica and General Therapeutics. By taking these courses, Douglass was finally able to expand her knowledge about women and natural sciences. The Materia Medica course might have been especially interesting to Douglass. According to the course catalogue, Douglass and her classmates were instructed in “the therapeutical properties of the various articles of the Materia Medica.” The course professor taught them “the natural and commercial history, together with the other properties of medicinal agents” through “an extensive collection of genuine and spurious drugs, drawings, dried specimens, &c.”[28] In effect, Douglass’ studies in medical school enabled her to attend to the properties of women and plants that went beyond their aesthetic beauty.

Douglass did not obtain a medical degree, but she still made use of the lessons she learned at the Female Medical College outside of the school’s lecture halls. After taking courses at the medical school, Douglass gave lectures on science, medicine, and health to African American women and, on occasion, men in Philadelphia and New York City. Douglass was praised and highly sought after for her lectures. For example, one commentator writing in 1859 in a newspaper called the Weekly Anglo-African, reported that Douglass’ lectures on “Anatomy, Physiology, and Hygiene” offered ample evidence against claims that women were unable to understand scientific knowledge or the workings of the human body. The commentator continued, writing that Douglass offered her audience “not mere details of scientific facts, but were enriched by numerous and beautiful illustrations, well calculated to elevate the mind, and so practical as to engage the attention of many on whom theories, however grand and inspiring, are lost.”[29] Perhaps Douglass reproduced illustrations of flowers during her public lectures that were similar to those drawings she contributed to the friendship albums.

These lectures were important to Douglass for several reasons. For one, giving public lectures helped supplement Douglass’ income. They also were part of her lifelong dedication to supporting African American people through education. As Douglass hoped, her lectures were of great practical utility to the Black women in attendance. For instance, in a letter from 1862, Douglass wrote to her friend Rebecca White about a lecture she had recently given. Douglass had evidently spoken about the anatomy of the eye, and she reported to her friend that at least two women in attendance had revealed to her that they benefitted from the presentation. One woman was able to identify that pains she had been having as actually stemming from the eye that Douglass must have discussed and subsequently told Douglass that she would take action to remedy it. Douglass wrote to Rebecca that:

Another woman told me that she had often felt what I described as coming from over exertion. She said after washing all and starching and hanging up till eleven o’clock she had often at that late hour taken her sewing and worked until her head ached and her eyes watered and yet she would persevere. Now she would rest herself and be better able to work next day.

After sharing this story with Rebecca White, Douglass concluded that she was “greatly encouraged to believe that a good work is begun.”[30]

In addition to the practical significance and benefits that education about natural sciences would have for African Americans, Douglass also believed that education was a valuable political tool. As historian Kabria Baumgartner argues in her 2019 book In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America, for Douglass, and other Black women and girls like her, education was connected to her activism because she believed that moral and intellectual development could bolster Black activists’ claims for freedom and equal status as citizens in the United States.[31] Douglass expressed the centrality of education to broader political activism best in her own words. “Our enemies know that education will elevate us to an equality with themselves. We also know, that it is of more importance to us than gold, yes, more to be desired than much fine gold.”[32]

Even before Douglass began giving public lectures in the 1850s, she was very involved in the education of African American women, men, and children. Douglass worked as a teacher in primary and secondary schools for over fifty years, mostly in Philadelphia and briefly in New York City. She also participated in the informal educational spaces of literary societies and lyceums that Black people established in Philadelphia.[33] As an educator, she taught her young students a variety of subjects, but it seems that she had a unique affinity for science education and the study of the natural world. For instance, an 1837 article of a Black-run newspaper called the Colored American featured some details about one of Douglass’ classrooms in Philadelphia. After reporting on the various intellectual activities available to Black people in the city, the author of the article singled out Douglass for “special notice.” He praised Douglass’ skill as a teacher and even noted the presence of “a well-selected and valuable cabinet of shells and minerals, well-arranged and labelled” in Douglass’ classroom. He concluded the article by stating that Douglass “has a mind richly furnished with a knowledge of these sciences, and she does not fail, through them, to lead up the minds of her pupils, through Nature, to Nature’s God.”[34]

Douglass continued to teach until she became too ill to do so in 1877. In a letter Douglass wrote to her friend Rebecca in March of 1876, shortly before her retirement, Douglass revealed how much she had enjoyed her career as a teacher. She wrote:

One of my old scholars here on a visit from South Carolina, said that she had heard a person remark (alluding to my suffering from rheumatism and my being obliged to go out every day rain or shine,) “Mrs. Douglass is dragging out a miserable existence” O said I eagerly, how she is mistaken! A miserable existence indeed! When I am doing the will of God concerning me! Doing the work I love; doing it with all my heart and soul and mind and strength!! Finding my rich record on high. I have thoroughly enjoyed teaching this autumn and winter. Going out morning by morning, leaning on the strong arm of my invisible friend and reaching my schoolroom with thanksgivings and praises in my heart and on my lips.[35]

Douglass clearly understood teaching African American people of all ages to be her divine purpose and part of her political struggle to better the condition of Black people in the United States. Ultimately, for Sarah Mapps Douglass the diligent study of the human and nonhuman aspects of the natural world was tied to her life-long mission of advocating for freedom and equality for Black children, women, and men.

Okay. For now, that is all I have to say about the fascinating career of Sarah Mapps Douglass and the environmental dimensions of her political activism. I hope you were able to enjoy learning about her in these past few minutes as much as I have these past few months. Thank you so much for listening!

Notes:

[1] I have made the decision to use first names for sake of clarity and therefore only in those cases when discussing family members who share a surname

[2] Julie Winch, The Elite of Our People: Joseph Willson’s Sketches of Black Upper-Class Life in Antebellum Philadelphia, (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000), 23.

[3] Robert Purvis, “Remarks on the Life and Character of James Forten, Delivered at Bethel Church, March 30, 1842,” 15, Black Abolitionist Papers, http://gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:bap:&rft_dat=xri:bap:rec:bap:03076.

[4] Anna Bustill, “The Bustill Family,” The Journal of Negro History 10, no. 4, (October 1925): 638-639.

[5] Julie Winch, Philadelphia’s Black Elite: Activism, Accommodation, and the Struggle for Autonomy, 1787-1484 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988), 5.

[6] Anna Bustill Smith, “The Bustill Family,” The Journal of Negro History 10, no. 4, (October 1925): 639.

[7] “Seventh Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female A. S. Society,” Pennsylvania Freeman, March 17, 1841, http://gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:bap:&rft_dat=xri:bap:rec:bap:06946.

[8] The Augustine Education Society of Pennsylvania, “Constitution,” in An Address Delivered at Bethel Church…before the Augustine Society, September 30, 1818, Black Abolitionist Papers, http://gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:bap:&rft_dat=xri:bap:rec:bap:07465.

[9] Erica Armstrong Dunbar, A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 85.

[10] J. J., “Mrs. Sarah M. Douglass,” Weekly Anglo-African, December 31, 1859, Black Abolitionist Papers, http://gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:bap:&rft_dat=xri:bap:rec:bap:10025.

[11] Amy Matilda Cassey, “Original & Selected Poetry, &c,” Amy Matilda Cassey album, Print Department, Library Company of Philadelphia.

[12] John Runcie, “Hunting the Nigs’ in Philadelphia: The Race Riot of August 1834,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 39, no. 2 (April 1972): 215; Emma Jones Lapansky, “‘Since They Got Those Separate Churches’: Afro-Americans and Racism in Jacksonian Philadelphia,” American Quarterly 32, no. 1 (April 1980): 64.

[13] “Sarah Forten to Angelina Grimké, April 15, 1837” in We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Dorothy Sterling (New York: W. W. Norton, 1984), 125.

[14] Gary Nash, Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia’s Black Community, 1720-1840, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988).

[15] The Library Company of Philadelphia, The Annual Report of the Library Company of Philadelphia for the Year of 1993 (Philadelphia: The Library Company of Philadelphia, 1993), 17-24 and The Library Company of Philadelphia, The Annual Report of the Library Company of Philadelphia for the Year of 1998 (Philadelphia: The Library Company of Philadelphia, 1998), 25-35.

[16] See Erica Armstrong Dunbar, A Fragile Freedom (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008) and Jasmine Nichole Cobb, Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2015).

[17] Britt Rusert, Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2017), 204.

[18] Daniela Bleichmar, Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 104.

[19] Sarah Mapps Douglass, “No marvel woman should love flowers…,” Amy Matilda Cassey album, Print Department, Library Company of Philadelphia.

[20] Letter from Sarah Mapps Douglass to Rebecca White, 1855, May 30, Josiah White Papers, 1797-1949, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections.

[21] Martha Jones, All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

[22] Erica Armstrong Dunbar, A Fragile Freedom, 127.

[23] Mary Forten, “Good Wives,” Amy Matilda Cassey album, Print Department, Library Company of Philadelphia.

[24] Erica Armstrong Dunbar, A Fragile Freedom, 130.

[25] “Sarah Grimke to Sarah Mapps Douglass [1854-55] in We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Dorothy Sterling (New York: W. W. Norton, 1984), 131-132.

[26] Dorothy Sterling, in We Are Your Sisters, 132.

[27] Angelina Grimké, An Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States: Issued by an Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, Held by Adjournments From the 9th to the 12th of May, 1837 (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838), 50.

[28] Third Annual Announcement and Catalogue of Students of the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania Located in Philadelphia at No. 229 Arch Street: For the Session 1852-1853, Women’s Medical College/Medical College of Pennsylvania publications, Drexel University Archives, Philadelphia.

[29] J. J., “Mrs. Sarah M. Douglass,” Weekly Anglo-African, December 31, 1859, Black Abolitionist Papers, http://gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:bap:&rft_dat=xri:bap:rec:bap:10025.

[30] Letter from Sarah Mapps Douglass to Rebecca White, 1862, February 9, Josiah White Papers, 1797-1949, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections.

[31] Kabria Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge, 6.

[32] Zillah, “Sympathy for Miss Crandall,” Emancipator, July 20, 1833, Black Abolitionist Papers. http://gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:bap:&rft_dat=xri:bap:rec:bap:05498.

[33] See Marie Lindhorst, “Politics in a Box: Sarah Mapps Douglass and the Female Literary Association, 1831-1833,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 65, no. 3 (Summer 1998): 263-278 ans Elizabeth McHenry, Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002).

[34] Samuel Cornish, “Editorial Correspondence,” Colored American, December 2, 1837, Black Abolitionist Papers, http://gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:bap:&rft_dat=xri:bap:rec:bap:11258.

[35] Letter from Sarah Mapps Douglass to Rebecca White, 1876, March, 27, Josiah White Papers, 1797-1949, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections.