By Rose Gilbert

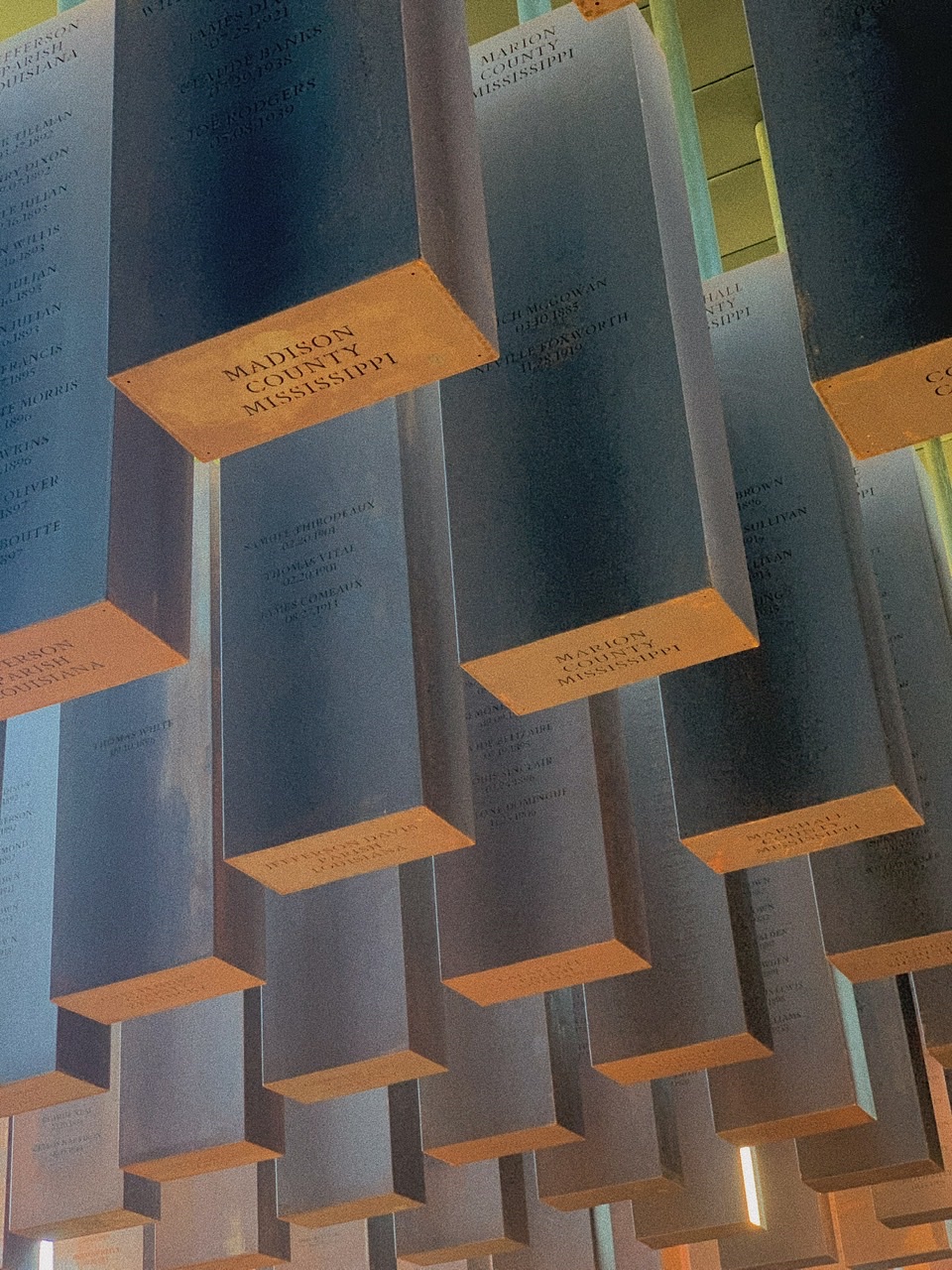

Tuesday morning in Montgomery broke bright and sunny. All of us were still emotionally hungover from the immense solemnity and outrage embodied in the Lynching Memorial, and none of us were fully focused on our breakfast.

Before leaving the city, we stopped for a brief visit at the Montgomery Riverfront Park. It was the perfect place to enjoy the warm fall weather, with a wide, smooth walkway wrapped along the bank of the Alabama River, featuring a shaded pavillion, an amphitheatre, and a splash pad I can imagine kids love during summer. A replica steamboat, all decked out with fake cobwebs and orange bows for Halloween, was docked right by the park entrance.

Like my own hometown’s steamboat, the Louisville Belle, this replica riverboat is a trapping of a time gone by, something to remind residents of their history and enthrall tourists looking for vestiges of the romantic Old South. Looking at it nestled amongst the park’s sleek poured concrete and tall electric street lights, I could see the story of a city that was trying to grapple with its past — as we had that morning — and what role it could play in its identity today.

Tourists today aren’t coming to Montgomery nostalgic for a romanticized, Gone with the Wind version of the South. Since the April 2018 opening, hundreds of thousands (including us) have poured into the city to visit of the National Monument for Peace and Justice and the accompanying Legacy Museum, driving business for local hotels, eateries, and shops.

There on the riverfront, I could see something of a lag in how the city is choosing to present their history, and nowhere was this more apparent than the historical markers scattered throughout the park. Some seemed like they could have fit in in any city: a plaque commemorating a local war hero, a high water marker remembering a long-ago flood. But it was a small exhibit on the history of Montgomery’s riverfront that caught my eye.

One of the markers, which detailed the history of the riverfront’s importance in trade, had been defaced; or rather, corrected. In the section explaining how the riverfront had made Montgomery a vital site for the trading, transport, and storage of “cotton and other important commodities,” one visitor had crossed out the word “commodities,” and replaced it with “slaves.” The correction was written in black Sharpie, and only visible against the sign’s dark background, like the editor couldn’t bear to leave the marker the way it was a moment longer and used whatever they had on them to fix it.