By: Mallory Williamson

After touching down in Montgomery on Sunday, our class didn’t waste much time before beginning the Civil Rights-era tour part of our Southern journey. Our first stop after getting lunch was at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

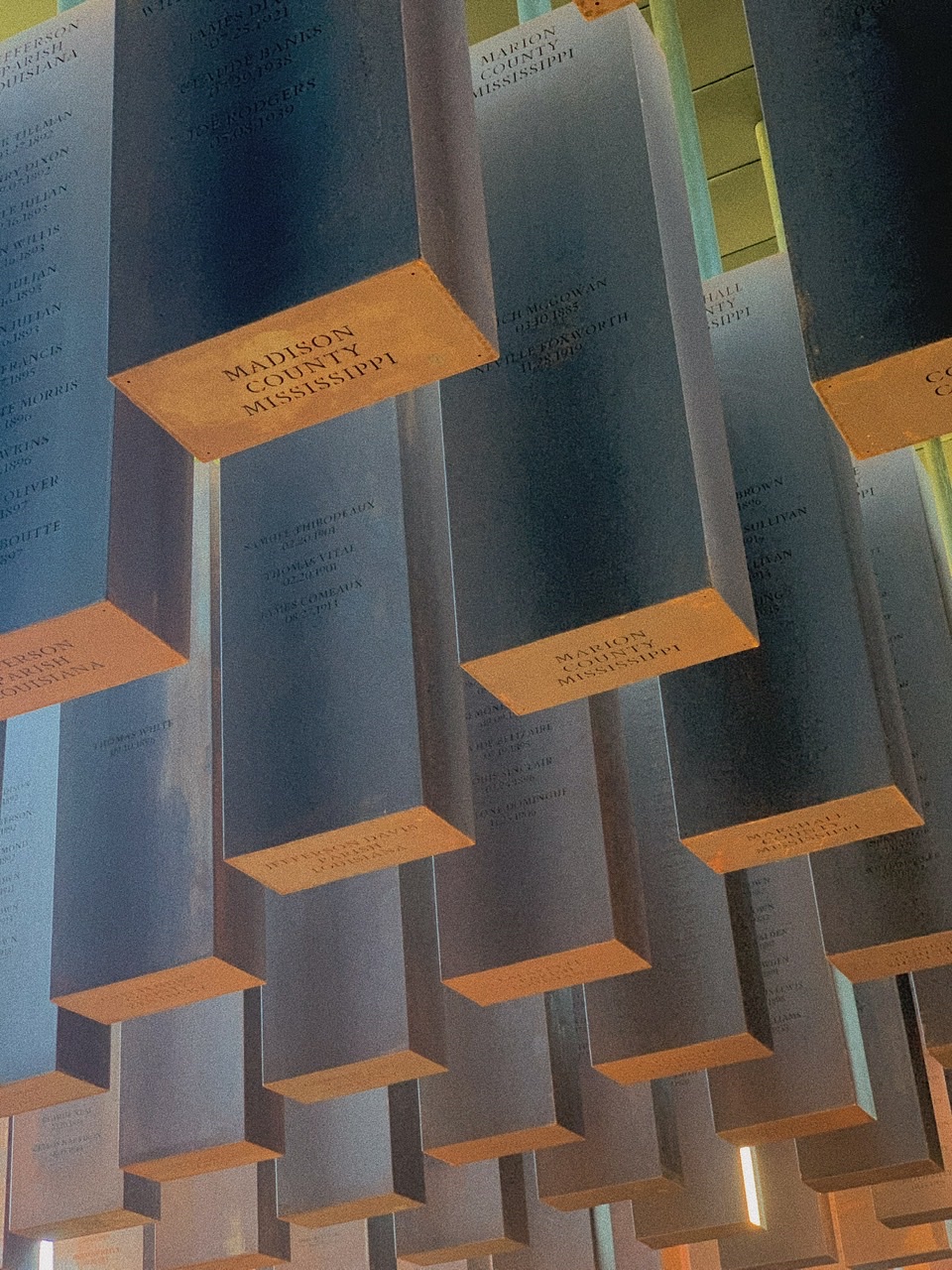

Also known as the Lynching Memorial, the site dedicated to known and unknown victims of lynching in the U.S. is considered a sacred place and is closely monitored by security officials. Once inside, we walked through spirals of hanging ‘coffins’ labeled with the name of a state or a county that list the names and death dates of all known lynching victims in that locality.

Across the street from the memorial was a small visitors’ center with rows of jars along its walls, each one filled with dirt from a lynching site and labeled with the victim’s name. Just as the county names on the hanging coffins give each lynching a haunting sense of place, the dirt from the lynching sites serves as a reminder that we unthinkingly walk on the same land where such atrocities might have occurred.

As someone whose roots are in the South—and whose hometown had a hanging coffin with three lynching victims listed—visiting the Lynching Memorial was a horrifying experience. The notion that the soil where my house stands and the woods where I played as a child could have been (and at least, were near) the site of something so horrendous was sobering. It is one thing to know in the abstract that our country was built on the backs of racial terror and another to confront that it’s happened in my neighborhood.

I am not particularly prone to outward displays of emotion, but I gasped audibly when I saw the name of the county where I’ve lived my whole life—and the ones where my parents, and their parents, spent their childhoods—listed among the hanging coffins. I’d realized fairly quickly upon entering the memorial that it was a possibility, but the irrefutable presentation that the fairly inconspicuous place where I grew up has such a dark, unerasable history rocked me.

It’s a privilege, as a young white woman with Southern heritage, to first think about football and sweet tea and orange leaves when I consider my roots. It’s also an incomplete thought—racial tension and terror are as entrenched in the South as the SEC — and I was reminded at the memorial that it’s necessary to temper my love for my home with the knowledge that its establishment is owed in no small part to forced labor and brutal discrimination.

I sent some friends of mine from home photos of the memorial soon after we’d left with a short explanation of what the names inscribed represented. After I’d sent the messages, though, I realized even the photos wouldn’t adequately convey the horror. I think it was the juxtaposition between the beautiful blue sky and green grass outside—the same kind of weather I most strongly associate with home—and the hanging reminders of what deep evil can transpire even on similarly gorgeous days that struck me most thoroughly.

Just as my subconscious knowledge that my South was the same South which fought a war to keep slavery had never truly been enough to make me consider the legacy of the land where I grew up, sending a photo or two in the high school group chat wasn’t likely going to be enough to make an impact.

Our visit to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, while horrifying, provided crucial historical context for the continuing oppression faced by Black people and communities which may feature centrally in the stories our class reports from Mound Bayou.