By Bryant Blount, Assistant Dean of Undergraduate Students:

When I was invited to accompany Joe Richman’s Audio Journalism class on their fall break trip, with only the context of a civil rights tour in the deep south, two thoughts flashed through my mind: First – how did I get tapped for this? Then, almost as quickly – I have to do it!

As an assistant dean at Princeton University, my work is almost exclusively the support of students in non-academic and co-curricular contexts. While my colleagues and I often assist students in the pursuit of activities and events that run adjacent to their academic interests, I can’t say I’ve had much, if any, proximity to credit-bearing work since I was last a student. Having supported traveling Princeton groups in the past, the opportunity to travel with this class on this unique excursion to Mound Bayou, Mississippi was altogether new. In addition to making sure we left Princeton’s campus with ten students (and perhaps more importantly, could account for all ten upon our return!), I hoped to be useful by picking up loose ends (or restaurant checks), taking advantage of the rich and deeply embedded lessons of the past found in the region (lapsed history major here), and perhaps most crucially, by documenting the experience.

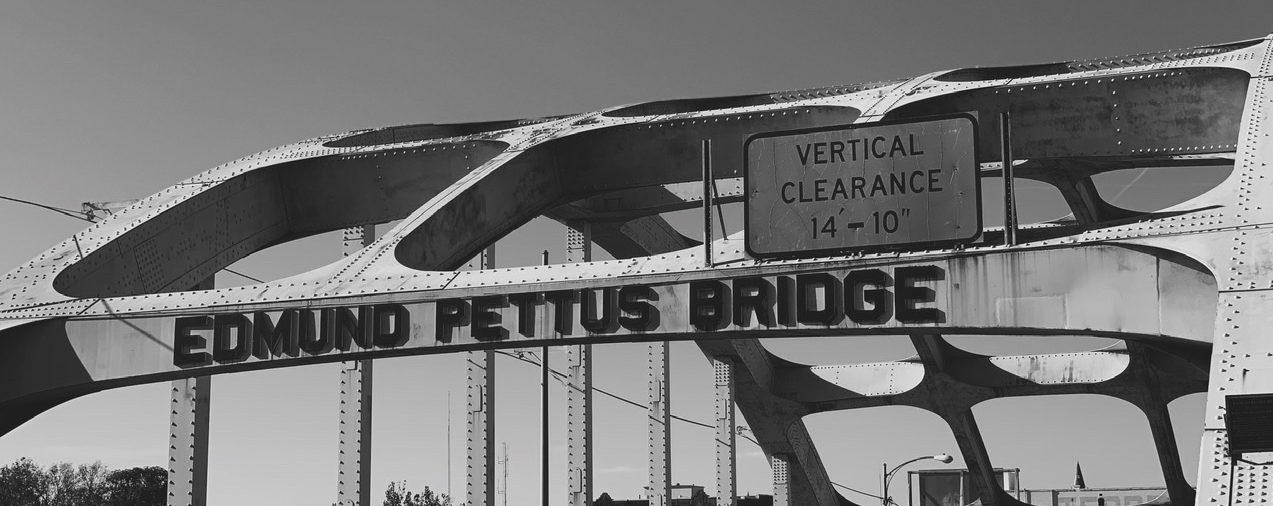

To this end, I shadowed the news team, taking photographs, some of which have been featured in this blog. I also captured video of the memorials, interviews, and people that made this trip an indelible one, in order to craft an audio/visual highlight that I hope will live on long beyond the week’s exploits. While the students in this class have a lot of work ahead of them as they drive toward their goal of producing a podcast series at semester’s end, this trip was more than the miles of bus rides, years of history, or hours of recordings that will be left on the cutting room floor. I hope that this video helps lift up their experience in fuller detail.