While preparing for our presentations this week, I found Rosalind Morris’ chapter on “Mediation and Mediumship in Thailand’s Information Age” to be especially impactful to my conceptualization of the relationships between culture and media, the past and present, and content producers and their imagined audience. In Chapter 20 of Media World, Morris explores the evolving practices of mediums, people who can communicate with spirits, in modern Thailand in order to elucidate how culture and mediumship mutually impact and define one another. Although I thoroughly enjoyed reading about the political economy of soap operas in Chapter 10, Morris’ analysis really resonated with me because it organically exposed how much my conceptualization of time and the cultural relationship between the past and present was influenced by the rhetoric of technological progress. As a native of the digital era, I have grown up immersed in zeitgeist that has been heavily influenced, if not defined, by tech companies. Whether it’s the PS5 or the iPhone 11, every year technology companies release new products that are supposed to supplant the ones that preceded it. This marketing implies that, as humans, the past is something that we are continuously moving away from, a place that we leave in the rear-view mirror as we barrel towards an idealized future. While this is a great way to create an artificial sense of urgency among consumers, this conceptualization completely dismisses the reciprocity of the relationship between the past and the present.

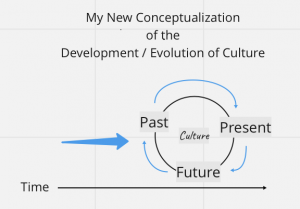

In Media Worlds, Morris essentially contends that the development of culture is the product of an ongoing tension between the past and present. As culture evolves and progresses, “there is nostalgia, a period of forgiveness in which the past becomes … that which is desired, that which wants to be ‘restored’”, that transitively impacts its development (386). In the case of Thai mediumship, it was “the perception of the relation of writing to orality as one of loss and irremediable absence” that summoned “the invention [and integration] of new media” (386). However, this phenomenon is also readily apparent in our social climate in the United States, as evidenced by the revanchism that has reemerged in response to the BLM movement and will undoubtedly influence future politics. Thus, through this nostalgia, the past often defines the present and shapes the future, making the relationship more cyclical than linear in many cases. This was a trend I had noticed in fashion with the reemergence of low waisted jeans, but prior to reading Morris’ ethnography, I had never considered that this dynamic could apply to the general formation and development of culture. However, the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. Instead of a series of steps building off of each other, moving forward towards some unforeseen goal, the evolution of culture is more like a wheel running on a track. To appropriate an example for class, when television was invented, live theater didn’t simply disappear. Rather, for many, the elimination of audience participation was a loss that reduced the authenticity and appeal of the representation, encouraging content creators, even decades later, to find new inventive ways to use new technology (ex. coding) to increase the interaction of the audience and restore what was lost, like with Black Mirror’s Bandersnatch. This new understanding of cultural development emphasizes the value and importance of analyzing cultural context and historical precedent through ethnography, because as William Faulkner once said, “the past is never dead. It’s not even past”.

Zack, this is very thoughtful. Looking forward to how you dig into this in your midterm essay.