Joe Bartusek, October 2, 2020

Post-productionOne aspect of the ethnographic study of Kayapo filmmaking that I couldn’t help thinking about, maybe because the other chapters I read in Media Worlds were in some way about this, was its tactile, corporeal properties. Similarly to how Zambians in the 80s and 90s conferred a certain social presence to radios and tape decks, which transferred to whoever was operating it at the time, cameras for the Kayapo seemed, at least through Turner’s Media Worlds article, to confer a degree of responsibility, although with the videographer retaining this responsibility through the tenure of his/her videographer position.

On another level, similarly in this case to the proliferation of corpothetic visuality via Indian chromolithography, cameras act as an extension of Kayapo cultural practices, and as a vehicle for the continued social creation which is notable of Kayapo culture.

Considering both of these connections, it would be easy to argue that cameras (and other recording devices, like the tape recorder on which the Kapot chief admonishes the Gorotire) were imbued with cultural and social meaning the moment they were introduced to the Kayapo, and were quickly integrated into Kayapo culture.

We talked a lot last class about the scene of the videographer in the center of the circle of a cultural performance. It would be interesting to tease apart the two elements in the center of the circle—the videographer, and the camera. Thinking specifically about the camera, as a recording device, in the center of the circle could provide a new perspective on the question of how videography itself fits into contemporary Kayapo culture, and whether it represents a disruption or a continuation of the “authentic” cultural practices which were there before it.

Lauren McGrath, October 2, 2020

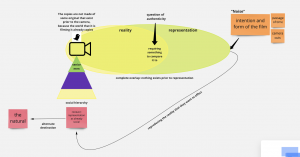

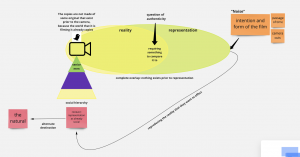

Post-productionHi all, in this week’s blog post I wanted to experiment with the “add media” function to insert a map of how I am starting to deconstruct our conversation yesterday in reference to Shannon’s model of communication.

I first started this map with our thoughts on authenticity; I felt that Rei’s comment on how authenticity can only be considered when there is something to compare it with (ex. prior to Western colonialism) was extremely important to visualize. I put this question at the center of overlapping circles because we discussed for the Kayapo, that it is necessary for representation to produce the social. The camera is also included in these circles, as the video is extending and participating in the ceremony and therefore the creation of social value.

I put the Kayapo social hierarchy (please excuse my typo on hierarchy on the image) underneath the camera because the concentration of social power is the highest at the center of the village (with the senior men); this shows how the camera becomes a potent form of reproducing Kayapo society. In this way, the whole production of society runs through the camera.

I also wanted to include the aspect of “noise” that Shannon’s model includes; I was thinking about how we discussed with film cuts that the camera-person changes positions but an inconclusive amount of time has passed. I additionally thought it was super interesting how Professor Himpele pointed out that the sound volume was the same in the film when the camera was in the center of the circle and in an aerial shot; I never noticed that beforehand. I feel like noise in this sense alters the intention and form of the film; would it then also affect the social value of the representation of the ceremony? I feel like because this model of communication has circular elements, rather than a linear model, I am continuing to find overlapping features and connecting elements.

I am excited to continue this conversation in class on Tuesday as we take apart media to analyze its’ construction.

Jerome Desrosiers, October 2, 2020

Post-productionAfter yesterday’s discussion about authenticity, I really wanted to dive in deeper in some aspects that came up to me. After the conversation on the two native communities and as we rewatched the clips from the natives and the shot went from inside the circle to outside the circle, I started thinking about the principle of authenticity from different perspectives. From what I understand, authenticity is dependable of perspective or point of view. We were discussing which group was more authentic but this can only go so far as we aren’t not activity part of either group and only have an “outsider’s perspectives”.

One could argue that we did in fact get a inside look as members of the community were given a camera to film their own experience from “inside the circle”, but again, how can one be certain when the camera is cut off, the subjects’ actions change completely? This is similar to Matthew’s point in his post-production post on reality TV that every action captured on screen could be totally fake but to the people watching, they seem authentic.

Matthew Gancayco, October 2, 2020

Post-productionThe subject of authenticity in this ethnographic work was troubling for me, as I feel that there is a natural dichotomy that occurs once a camera is brought into play. What is considered to be authentic when a camera is and isn’t rolling are inevitably going to be different when the person knows that they are being filmed. In the third chapter of Media worlds Turner argues that giving the camera to the Kayapo is a way of escaping the implications of intervention. In theory, is the introduction of the camera not the most important intervention.

We discussed in class how there were times in the film where the natives were surely influenced, if not putting on an entire act, for the camera, whether or not the camera person was one of their own. When the chief was on the radio lecturing the other villages, his actions cannot be seen as authentic. Once the camera starts rolling, the validity of ones actions come into question. Even the minute details such as when a person looks into or smiles at the camera, reduces the authenticity.

I would equate the phenomenon to what occurs with “reality television.” These tv shows like the “Jersey Shore” or “Keeping up with the Kardashians,” are meant to be representations of their every day lives. But its obvious that their actions and conversations are dramatized for audiences to enjoy and find more interesting. There was a scene in the film where a male kayapo was brandishing a bow and arrow for the camera. He was boasting how he was going to kill with it and motioning how he would do so. This in my opinion is a similar situation, where someone is behaving differently in front of a camera.

Rei Zhang, October 1, 2020

Post-productionI watched the Kayapo Documentary before I read the associated chapter, so when watching, I had one immediate question: who was the narrator and who was making the film? I didn’t get an answer until the very end of the film – it isn’t until the credits that the viewer learns who the associated anthropologist and videographers are. Terence Turner doesn’t insert himself into the film – his presence remains unseen and he endeavors not to speak in the videos, instead choosing to narrate over clips or allowing the Kayapo to speak for themselves. He also seems to edit out his questions and prompts, only showing the Kayapo’s responses to those questions.

In fact, the first time a cameraperson (I’m assuming it’s Turner, although I could be wrong) speaks and inserts himself into the narrative is to ask a question at around the 10:50 mark. (Notably, his other insertion into the film’s narrative is at the end, when the narrator makes an ‘I’ statement regarding his observations about the Kayapo’s dancing rituals and the likelihood of those rituals being performed after a political victory.)

Turner, by attempting to remove his presence from the documentary, seemed to me to be attempting to present a more ‘objective’ view of events. It reminds me of the way Edward Lane disguises himself to “pass” in Egypt. In the same way that Lane tried to make his positionality of European as irrelevant, Turner seems to also attempt to remove his positionality as a Western anthropologist, by removing his questions and by using clips filmed by the Kayapo where possible. This also connects to the preconceived notion we have that a more direct experience (of culture, aka immersion) equals a more real experience.

But, as we’ve previously considered, objectivity is not necessarily possible – there is no objective observer, and there is no objective videographer. I think that Turner, by failing or neglecting to inform viewers of his own positionality, removes a valuable angle with which to further analyze the portrayal of the Kayapo and the layers of culture in the film.

Zack Kurtovich, October 1, 2020

Post-productionFor this week’s post, I would like to build off of Grace’s fantastic post-production from September 24th to offer new insight into the following questions: what purpose does ethnography serve in media studies? What are ethnography’s strengths and weaknesses, and how does this impact its ultimate message? While, like Grace, I don’t have a conclusive answer, my hope is that this post can function as a springboard for others to further this discussion in the coming weeks.

To begin, I feel it is critical to point out that ethnography’s power lies in its localization and contextualization, which is what makes it uniquely equipped to decipher and unpack media studies’ cacophony of information. As the introduction of Media World touches on, technological modernity has both homogenized and divided cultures around the globe, making ethnography’s capacity to understand the “persistence of difference and the importance of locality while highlighting the forms of inequality that continue to structure our world” increasingly important (Media Worlds, p 25). The propensity of ethnographers to “‘work ‘close to the ground’ and at the ‘margins’” provides them with a specialized, contextual knowledge situated in the specific socio-historical environment of interest, enabling them to better identify and interpret the medium’s rhetorical appeals to its imagined audience (Media Worlds, p 24). By forming an intimate relationship with the cultural context while maintaining a necessary distance, ethnography allows anthropologists to engage and contribute to larger discussions concerning media studies, globalization, and cultural imperialism in distinct, nuanced ways.

Interestingly, however, ethnography’s contextualization can also be perceived as one of its largest weaknesses, as it often heavily relies on cultural interpretation. Like all forms of representation, ethnography has the potential to take on some of the value judgements of the anthropologist, as we extensively discussed during on conversation on Mitchel. This presents a number of challenges, as anthropologists are tasked with taking into consideration the motivations, biases and interests of the involved parties while accounting for their own. As Grace pointed out in her post-production, part of how ethnographers are able to do this is through the intense interrogation of the media’s pretext (What was the creator’s intended reaction? How was it received?, etc). However, it is often more difficult to ask those hard-hitting questions, and get painfully truthful answers, from yourself. While those questions are certainly vital to execute a successful ethnographic study and understand the media of interest, all of them could also be asked of the ethnography itself. What is the ethnography’s intended purpose or reaction? What is its goal? How has the author’s own cultural pretext influenced their study and its findings?

As such, ethnography, in many ways, is a precarious balancing act. Although we have frequently framed the discussion around the investigation of the studied media’s motivations and interests, I feel like it is important to remember that ethnography is also a medium and like other forms of media, it is not immune to the influence of context and culture. Simply because one is writing from the perspective of an outsider does not mean they are situated outside of culture’s web. As we continue to engage in these conversations, I will have to get better at keeping this in mind and interrogating all forms of media, including the ethnography itself. See you all in class!

Anna Durak, September 25, 2020

Post-productionAfter yesterday’s discussion, I found myself still considering Professor Himpele’s comment about the producer being a member of their audience. The title of the presentation that Ailee and I completed this week was “(H)industrialization: how do filmmakers imagine their audiences?” But we never stopped to think of the filmmaker as a part of their own audience. Similarly, when I brought up a previous paper I had written about the influence of film on the collective memory of WWII, I had never stopped to think explicitly about the influence of the filmmaker as an audience member.

The article, “And Yet Mt Heart Is Still Indian,” by Ganti starts with the description of the Bollywood filmmakers being an audience to the film Fatal Attraction. They are audiences to the film in which they are trying to replicate, attempting to inject their own culture and media into an established media. In order for a filmmaker to make a film that resonates with the audience, there must be a shared understanding of what the audience expects/wants from a film. Similar to Ailee’s comment in class about Hollywood directors now making movies about what they want to see, I believe we are able to distinguish the filmmaker’s role as an audience member if we further unpack their roles in representational media. In order for movies to be greenlit and created, they must be approved by many people, not just one individual. The media must be approved by culture before the media can become an influential piece of data used to inform culture. In that vein of thinking, would modern culture, which is heavily influenced by media, be merely the byproduct of a collection of filmmakers’ culture? I am thinking of the ways in which scenes are repeated, recycled, or at least inspired by past media and the ways in which filmmakers translate their experience as an audience of the original media, into the art and media which they late recreate for another audience.

Lauren McGrath, September 25, 2020

Post-productionIn this blog post I wanted to continue our discussion on the subject of audience and how that contextualizes or informs media produced (from my preconceptions to my newfound thinking because of our in-class discussions). My concept of media was changed this week when we talked about how media is organized around the “imagined audience” and how cultural conceptions of what the “ideal audience” is demonstrates how power comes into play in what messages are reinforced through media (pulling from Ailee and Anna’s presentation on the differences between Bollywood and Hollywood film production). However, many of the ethnographies we focused on did not explicitly interact with the targeted audience of media, but rather discussed the audience through the imagined and constructed audience that producers utilize ahead of the production process.

What if film companies that produce media involved the actual audience of the film into its creation? I am thinking about when the “imagined audience” discussed in the context of the Bollywood films no longer is imaginary: would this not work/create the same problems because the individuals/audience members “chosen” to almost consult on the film would be what the producers “imagined” their audience to be anyway? On the other hand, could that change the power dynamics of media creation or change the end net result?

I was also wondering (in our discussion of the Balinese live vs televised theater) if an ethnography that investigated the questions that I listed above would further blur the line between the outside world and media.

Honestly, I have more questions than I do answers, so I would love to discuss this further and hear everyone’s thoughts in either the comments or in class.

Zack Kurtovich, September 25, 2020

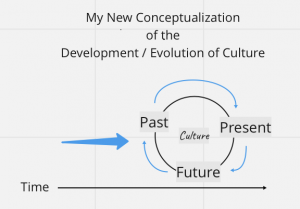

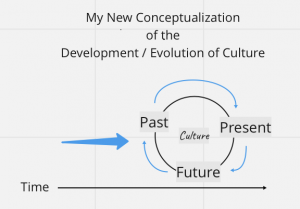

Post-productionWhile preparing for our presentations this week, I found Rosalind Morris’ chapter on “Mediation and Mediumship in Thailand’s Information Age” to be especially impactful to my conceptualization of the relationships between culture and media, the past and present, and content producers and their imagined audience. In Chapter 20 of Media World, Morris explores the evolving practices of mediums, people who can communicate with spirits, in modern Thailand in order to elucidate how culture and mediumship mutually impact and define one another. Although I thoroughly enjoyed reading about the political economy of soap operas in Chapter 10, Morris’ analysis really resonated with me because it organically exposed how much my conceptualization of time and the cultural relationship between the past and present was influenced by the rhetoric of technological progress. As a native of the digital era, I have grown up immersed in zeitgeist that has been heavily influenced, if not defined, by tech companies. Whether it’s the PS5 or the iPhone 11, every year technology companies release new products that are supposed to supplant the ones that preceded it. This marketing implies that, as humans, the past is something that we are continuously moving away from, a place that we leave in the rear-view mirror as we barrel towards an idealized future. While this is a great way to create an artificial sense of urgency among consumers, this conceptualization completely dismisses the reciprocity of the relationship between the past and the present.

In Media Worlds, Morris essentially contends that the development of culture is the product of an ongoing tension between the past and present. As culture evolves and progresses, “there is nostalgia, a period of forgiveness in which the past becomes … that which is desired, that which wants to be ‘restored’”, that transitively impacts its development (386). In the case of Thai mediumship, it was “the perception of the relation of writing to orality as one of loss and irremediable absence” that summoned “the invention [and integration] of new media” (386). However, this phenomenon is also readily apparent in our social climate in the United States, as evidenced by the revanchism that has reemerged in response to the BLM movement and will undoubtedly influence future politics. Thus, through this nostalgia, the past often defines the present and shapes the future, making the relationship more cyclical than linear in many cases. This was a trend I had noticed in fashion with the reemergence of low waisted jeans, but prior to reading Morris’ ethnography, I had never considered that this dynamic could apply to the general formation and development of culture. However, the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. Instead of a series of steps building off of each other, moving forward towards some unforeseen goal, the evolution of culture is more like a wheel running on a track. To appropriate an example for class, when television was invented, live theater didn’t simply disappear. Rather, for many, the elimination of audience participation was a loss that reduced the authenticity and appeal of the representation, encouraging content creators, even decades later, to find new inventive ways to use new technology (ex. coding) to increase the interaction of the audience and restore what was lost, like with Black Mirror’s Bandersnatch. This new understanding of cultural development emphasizes the value and importance of analyzing cultural context and historical precedent through ethnography, because as William Faulkner once said, “the past is never dead. It’s not even past”.

Jerome Desrosiers, September 25, 2020

Post-productionI really liked this week’s presentation and discussion. So much so that I want to reemphasize one thing that I mentioned during Joe and I’s presentation on the elements of Dashan. On Tuesday, I mentioned that the Zambian culture considers the radio as part of their culture rather than an addition to it. Like professor said, it is an ingredient to their culture recipe. On Thursday we touched on this notion of “double sensation” which can be explained by “touch and be touched”. This is what I think is key is the relationship between culture and media. It also relates back to the relationship between the producer and the audience meaning that anyone can play either role at any point in time (which is also why social media apps are so popular nowadays).

Maya raises a good question in her post which questions if media can be produced without an audience in mind? This question made me think of another one: Can one be the producer as well as the audience at the same time? In other words can a producer of media be its own audience? To me, this would still fall under the notion of double sensation as the content produced still affects the producer in one way or the other. But what do you and professor think?

Emily Yu, September 24, 2020

Post-productionA large portion of our discussion today was addressing the role of the audience within media production and consumption. I had a few thoughts about the idea of an audience.

First, I think we never really got to defining what an audience even is – is it an individual, a group of individuals at the same time or place (like in the case of the Balinese theater), or just individuals spread out over time and location that consume some of the same media (i.e. people watching Bandersnatch from their own homes at different times), or does an audience even have to be human for a message to be received (like Rei brought up about transmission)? Or perhaps does it really not matter what the true audience is in the first place because there lives this separate, imagined audience that is constructed in the minds of the producers? Furthermore, this idea of constructing an audience seems rather counterintuitive in some contexts, as in contexts that aren’t on a national or global scale. For example, when exploring Hmong media, it is precisely because the producers are able to read the text – the wants, needs, culture – of the Hmong Americans, that their films are already successful; there is no need for a construction of an audience.

Furthermore, we acknowledged that a producer cannot distance themselves from their work and is thus part of the consumers and is the audience. However, there seems to be an implicit distinction that we are making between the producer, who is an individual who is part of the audience, and the everyone else, who seems to not to be individuals and are grouped under this label of “mass audience.”

In that vein, I think the portrayal of the audience is particularly interesting the case of Cynthia and Grace’s presentation on Hispanic identity. They mentioned this idea of a creation and erasure of Hispanic identity that comes with targeted advertising. The producers seem to be in the active role, extrapolating information about culture from existing medias in order to shape some message that they hope the audience will receive. And it is only because the audience accepts this message that there is this creation and homogenization of the Hispanic culture that somehow becomes accepted as reality. And it seems implicit that this acceptance is much Shannon’s model where the message is received, without noise, from the transmitter.

Grace Logan, September 24, 2020

Post-productionOne of the many interesting questions that was raised in class today that I am still thinking about is: what is ethnography doing in media studies? Though I do not have a solid answer for this yet (and I wonder if there is an answer), I am thinking that many of the presentations we have seen point to the audience as a significant piece of ethnographic studies of media. Today we discussed how many of the readings implied, and Dornfeld even explicitly stated, that the producers of media anticipate and imagine their audience beforehand. An observation (that I think Maya made) in response to this is that the reactions and responses of the audience can be variable. This is something that is not captured in Claude Shannon’s model of communication which only shows one receiver (yeah, it was definitely Maya who brought that up). What I also began to consider is how Shannon’s model also neglects to account for multiple information sources. I am considering information sources to be the producers of the media. The chapter that Cynthia and I presented on Childhood made it very clear that multiple agents and entities with their own motives and pretexts negotiated throughout the pre-production and production of the series which ultimately shaped the final product. To bring this back to the question of what ethnography does here, it is possible that one of the functions of ethnography in media studies is to look more in depth at these varied reactions to consumption of media and motives for producing media. Possible questions that an ethnographer may ask is: what reaction was the producer anticipating? How do the various producers and funders imagine the goal of their product? What has been compromised on during production and why? Where are the variations in reactions, and what explains them? And if time allows, what is the producer’s or industry’s response to their audience’s feedback?

I am very interested in considering how the issue of audience expectation and feedback arises in social media, which seems to accelerate the feedback loop. Social media posters and influencers can almost instantly see feedback to their post qualitatively through comments and reactionary posts as well as quantitatively through likes, shares, retweets, views, etc.

Maya Stepansky, September 24, 2020

Post-productionOur talk today about audiences and their role in media consumption and in the Shannon diagram of communication made me wonder what would happen when media is constructed without an audience in mind. Does media created for media sake really fit into Shannon’s communication model if there is no explicit audience that the creator is trying to target? Possibly, this absence of an audience would no longer allow it to fit into Shannon’s model of communication since there is no receiver. Or, possibly, the creator of this audience-less media is both at the informative and receptive ends of the line of communication. If we are rolling with this idea, then the creator is literally making media for themself and no else and is using media to communicate to him/herself. Probably, this type of inward/personal/one-way communication through the use of media could really highlight how exactly media affects/distorts/or doesn’t change the communication of an originally intended message. I could imagine a filmmaker starting a project with a clear purpose or message that he/she wants to prove or communicate to him/herself, but through the thorough process of production and actual filmmaking, they end up communicating an entirely different message. This is leading me to a question that is certainly an overarching theme in this class: Does the use of media affect or distort an originally intended message by the creator? And if so, to what degree is the message distorted or changed–how is it changed? Possibly an audience-less study of a “media for media’s sake” project can help answer this question.

Comments

Joe – a very evocative post. It shows the influence of the Spitulnik essay for interpreting camera as a material ingredient of Kayapo society. Taking the Kayapo cultural and social meanings of video in their own terms, however, how would they answer the question about the authenticity of video representation?