Personalized advertisements and there accuracy have been a hot topic for the past couple years. As someone who often experiences the phenomenon of thinking about a product and it appearing in an ad while I’m surfing the web, I find it both convenient and unsettling that websites are becoming so effective at targeting audiences. It makes it hard to believe that the phone isn’t listening to you. Or is it?

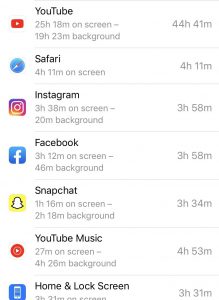

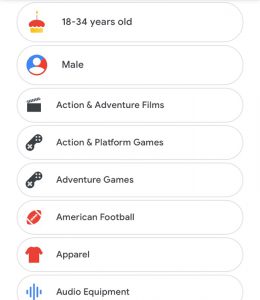

I admit that my phone has become an attachment of my body at this point. After opening my phone activity for the past 10 days, the average screen time per day was 8 hours. The most used app was Youtube, which I had used for a staggering 45 hours during the 10 day period. I like to keep videos playing in the background during the day, whether it be while exercising, cooking, etc. For my data entry, I decided to look at the ad personalization that Google had given to me. Google has a list of ad categories that it believed to be preferable for me. This list is generated from my profile and activity. As I sifted through the list, most of the categories seemed accurate, such as comedy and video games. There were occasional categories in the list that seemed completely inaccurate such as patio/lawn care or swimming. This data is based on past activity, so although I may have clicked on a video in the past I may have no interest in the topic.

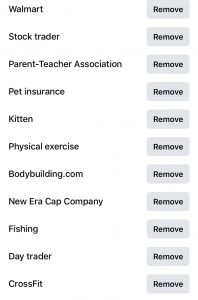

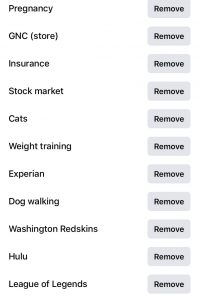

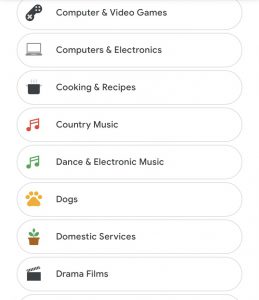

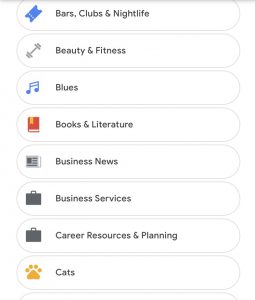

In order to measure the accuracy of Youtube’s digital identity for me, I pulled up the ad personalization that Facebook, a website I use much less, had documented for me since I created the account in 2009. As expected, Facebook’s list was much longer and more broad. It also includes specific things such as sports teams, actors or businesses. The list is made from my profile and pages/ads I have clicked in the past, so the range varies greatly. There are too many to include in this post.

For both Google and Facebook, my identity was based on my activity on the platform. Therefore, all the site can gather is what I prefer when using that specific platform. The fact that I use Youtube more frequently enables it to be more accurate than Facebook.

This data could be divided into two categories, that which is accurate and inaccurate. Just going off of my clicks, both sites will not be able to decipher between my interests and disinterests. I may click on some subjects more than others, but the existence of a click on a video or ad implies interest. If it were possible to look at every click I’ve made on both sites and divide them into an interest and disinterest, my digital identity be more accurate.

The limitation of the platform of basing your identity off of usage is the most obvious. Both websites can only analyze your activity, so if you aren’t active your identity will be inaccurate. In many ways this data used to be considered private, but I would argue that this data is now public and the only private data you own is that which isn’t recorded.

Recently, a class action lawsuit was filed against Google for tracking user data when using incognito mode. Although it is advertised to be a private browser mode, websites were able to mine information from users while using the setting. This is just another reason why what used to be considered private data is in fact the opposite.

Phone Activity

youtube

Hey Mathew, I think it is interesting to use “inaccurate” and “accurate” as the categories for the data you found on yourself. I also looked at my Google ad settings and found many of the characteristics and interests to be surprisingly inaccurate as well. That is an important point you make about a click alone implying interest, I definitely agree that being able to divide up each individual click into “interest” and “disinterest” would create a more refined “pixelated self”. For my own post I had looked at the reasons that Google thought I had these interests and found that having a similar search/watch history to others who have the same interests seemed like a more accurate representation of my own. I wonder if this has something to do with scale, as we commonly accept that a larger amount of data points would result in a more accurate or refined answer, and in this case ad preferences, but I do not know enough about the mechanics behind this to say. This leads me to think that just clicking on something or visiting a site is far more arbitrary than Google is assuming. However, then again I also realize that these are for constructing ad preferences, in which the ultimate goal is to sell you something. So I guess it would make sense to try to sell you something that you may be mildly interested in, enough to click on once, but probably do not already own/subscribe to.

Also, I think your observation that the only data that is truly private is the data that isn’t recorded is interesting. I am leaning towards agreement on this one, but I still want to be optimistic. This question is making me think more about how exactly we define public. Does it mean accessible or viewable to everyone? Does it mean that it is identifiable? Considering that companies are selling data to one another, essentially selling access to it, maybe it does not seem public in that sense. However, the audience then of this data is much different than we probably initially anticipated, and so it is more public than intended.