Table of Contents

Who is Shirley?

U.S. Rep. Chisholm Brings Intersectionality to Congress

Ms. Chis for Pres

The Chisholm Effect & Black Female Politics

Sources & Resources

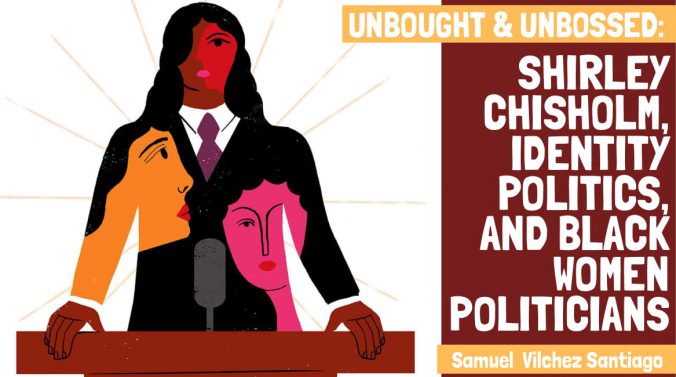

This digital project explores “identity politics” through the lens of Shirley Chisholm’s political career, reflecting on her contributions and impact on other black female political leaders in the United States.

Black women in politics operate at the intersection of their blackness and womanhood

When people hear the term “identity politics,” most people think of the utilization of a politician’s race and/or gender identity to advance their own political careers. Specifically, in the modern political context, the concept of “identity politics” is often used to frame the candidacies of marginalized (i.e. non-white, non-male) politicians, which operate in a field dominated by rich white men. Whether it is identifying as female or coming from a racially marginalized community, a minority candidate’s campaign-related decisions, policy proposals, and ideological leanings tend to be minimized and supplanted by society’s focus on their identities.

This narrow take on “identity politics” ignores the prolonged history of politicians’ utilization of whiteness and masculinity to advance their careers. Particularly, while the term “identity politics” is often used to denigrate the policy proposals and campaign tactics of candidates who hold marginalized status, the reality is that, throughout American history, white men have benefitted the most from “identity politics.”

While much discussed, the concept of “identity politics” is rarely defined with much clarity. To center this often nebulous debate, this project uses the definition provided by Harvard psychology professor Steve Pinker, who sees “identity politics” as:

“The syndrome in which people’s beliefs and interests are assumed to be determined by their membership in groups, particularly their sex, race, sexual orientation, and disability status. Its signature is the tic of preceding a statement with ‘As a,’ as if that bore on the cogency of what was to follow.”

With this framework in mind, this project examines the notorious political career of Shirley Chisholm, which exemplifies how Pinker’s definition of “identity politics” operates as a political practice. Particularly, by not shying away from utilizing her marginalized racial and gender identities, Chisholm provides a model that is similar to the identity-heavy approach taken by white men throughout American political history. That is, Chisholm utilized the intersectionality of her racial and gender identities to advance both her Congressional tenure and historic presidential campaign. More specifically, through the evaluation of Chisholm’s political career, this website shows how “identity politics” can operate as a successful political practice, especially among black female politicians.

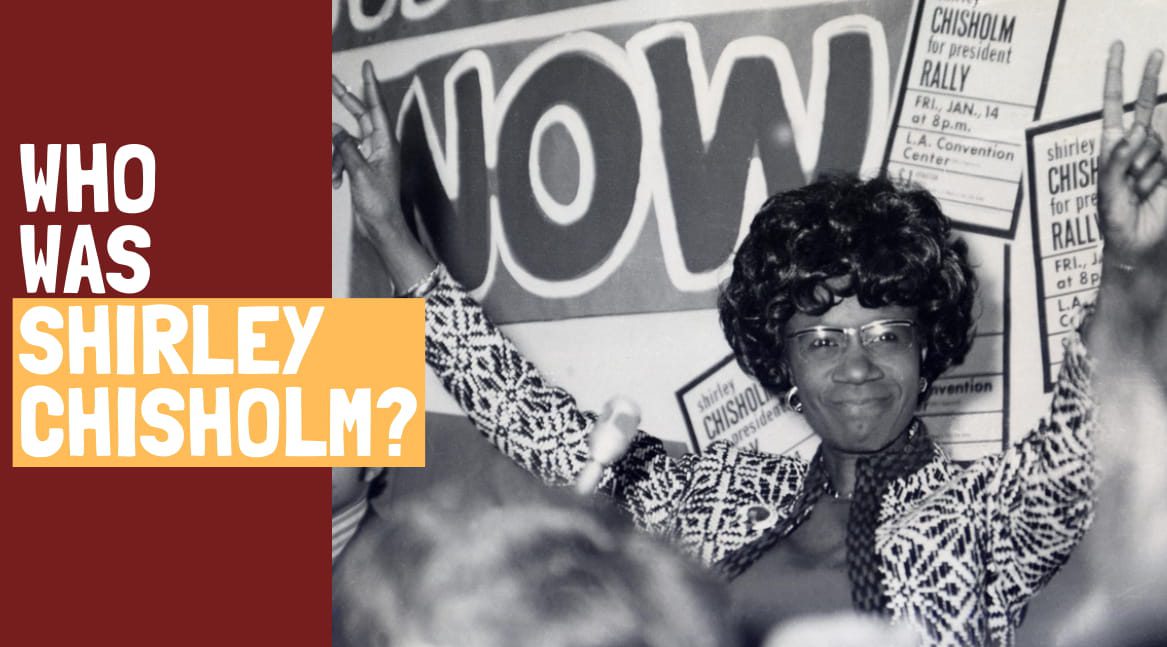

Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1924 to parents from Barbados and Guyana, Shirley Chisholm was the first black Congresswoman in American history, representing NY’s 12th Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1969 to 1983. Before being elected to Congress in 1968, Chisholm, a graduate of Brooklyn College and Columbia University’s Teachers College, had served New Yorkers as a State Assembly member for four years. She had also worked as the Director of the Hamilton-Madison child care center, where she first became involved in politics.

In January 1972, Chisholm announced her candidacy for the Presidency of the United States, becoming not only the first black major-party candidate but also the first woman ever to run for the Democratic Presidential nomination. In the 1972 Democratic Presidential Primaries, she received over 430 thousand votes (2.7%), coming in at fourth place with over 150 delegates.

Given her historic career, Chisholm, who died in 2005, has become a political idol for many Americans, especially in feminist, liberal, and black political circles.

This interactive timeline highlights the pivotal moments of Chisholm’s life and career:

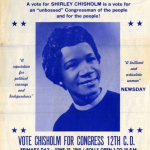

Throughout her four years in the New York State Assembly, Chisholm successfuly advocated for improving childhood education, employment benefits for domestic workers, and maternity leave for female teachers, helping to pass legislation to those ends. Building on those legislative victories, in 1948, Chisholm ran to represent Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant community as well as other parts of the borough in the U.S. House of Representatives. In a contentious race against James Farmer, a black male civil rights leader who ran as a Republican, Chisholm reached out to different minority communities. For instance, she often spoke Spanish – a language she learned as a school teacher – to Puerto Ricans and other Spanish-speaking voters. The race was was filled with sexist attacks against Chisholm:

“Another of the personal issues in the campaign is that Mrs. Chisholm is a woman, and Negroes, particularly militant males, are reacting to generations of ‘matriarchal dominance.’ While Mr. Farmer does not assail Mrs. Chisholm directly, his printed matter dwells on the need for a ‘strong male image’ and ‘a man’s voice in Washington.”

Chisholm responded by stating:

“I have always spoken out for what I believe: I cannot be controlled.”

On Election Night – November 5, 1968 – Chisholm won with over two thirds of the votes, making history by becoming the country’s first African American woman elected to Congress. Here is how the African American magazine Ebony reported Chisholm’s victory:

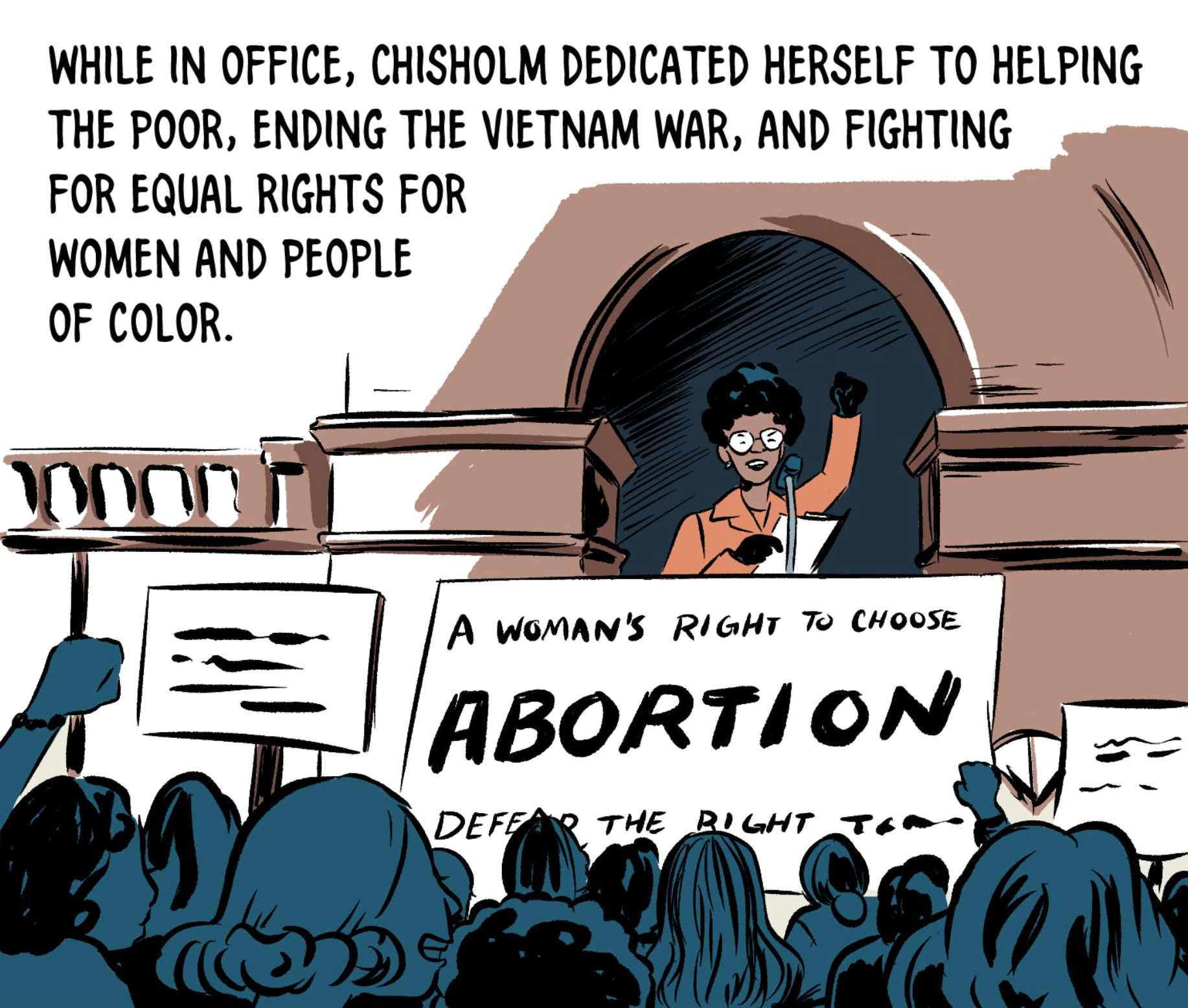

Chisholm would go on to serve NY’s 12th Congressional District for seven consecutive terms, from 1969 to 1983. During her 14-year congressional tenure, she brought an intersectional approach to policy-making, seeking to support marginalized communities, including the poor, women, and people of color.

Chisholm also played a key role in the establishment of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), increasing federal funding to extend the hours of daycare facilities, and overriding President Ford’s veto on a national school lunch bill.

Similarly, Chisholm’s commitment to the advancement of social justice for women and people of color extended outside of policy-making, and into the political. For instance, she hired all women for her office, half of whom were black.

In 1971, Chisholm became the only woman founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus.

Founding members of the CBC

In 1976, Chisholm campaigned to become part of the Democratic House Leadership team, running to become House Caucus Chair. While losing to Washington’s Tom Foley, her campaign slogan “Give Your Chair to a Lady” demonstrated she was willing to put her race and gender front and center.

In 1977, Chisholm became one of the 15 founding members of the Congresswomen’s Caucus, which primarily fought to expand the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

Some of the founding members of the Congresswomen’s Caucus

During her time in Congress, Chisholm served on several House committees, including Agriculture, Veterans’ Affairs, Rules and Education, and Labor. In 1976, Chisholm made history again by being assigned to the powerful House Rules committee.

Chisholm was often the only woman and black person in different Congressional Committees, including the powerful Rules Committee

As a black woman, Chisholm was on the receiving end of discriminatory verbal aggressions by several of her colleagues. This was not necessarily due to Chisholm’s unapologetic deployment of her racial and gender identities, but simply because, as the first black woman in Congress, she represented a form of threat to the white male status quo. Thus, Chisholm’s open approach to the utilization of her identities appears correct. Even if she tried to stay away from highlighting her identities, Chisholm would have still been discriminated against just because she was different than her colleagues. Chisholm reflected on how she approached racism, sexism, and discrimination in Congress:

Overall, during her fourteen years in Congress, Chisholm connected her political strategy and policy proposals to identity, often emphasizing the intersectional nature of how people – politicians and constituents alike – are affected by the marginalization of their identities. That is, Chisholm did not only understand how the creation of affinity caucuses would create more power among non-male, non-white Members of Congress but also how those caucuses could positively impact the policy-making process in favor of marginalized communities. At the same time, as the interview demonstrates, Chisholm’s intersectional identities were also the source of much discrimination from her congressional colleagues.

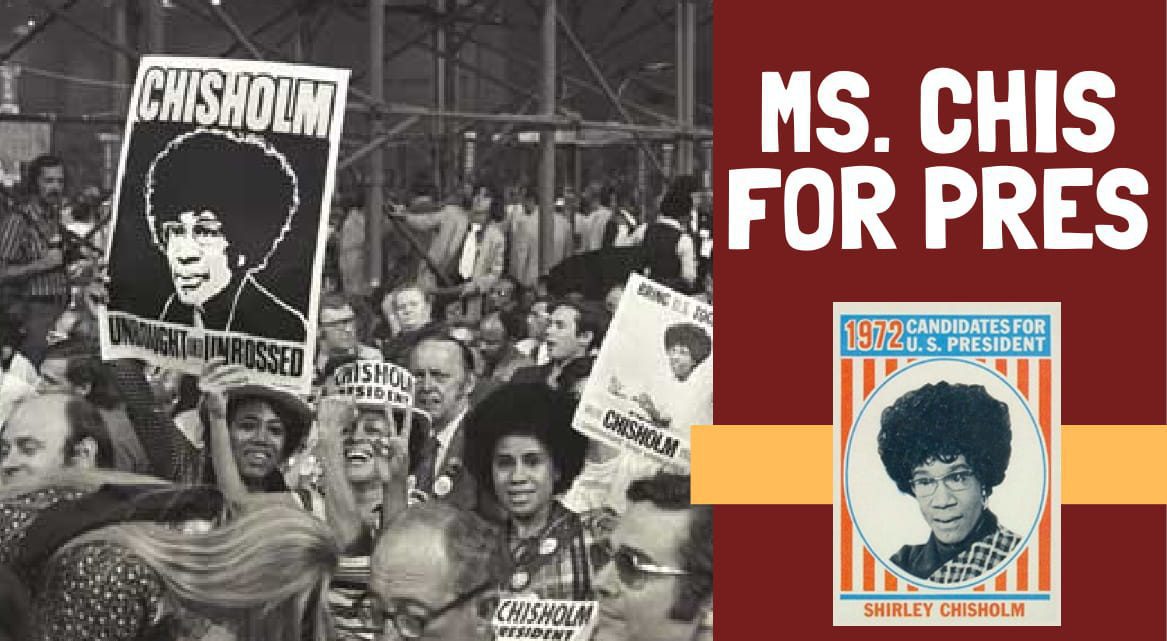

In January 1972, Chisholm announced her candidacy for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States, becoming the first woman and black person in American history to do so. This Timeline video report summarizes Chisholm’s historic presidential campaign:

As Timeline’s video highlights, Chisholm’s identities played a pivotal role in the campaign trail, both positively and negatively. Positively, throughout the campaign, Chisholm proudly employed her racial and gender identities. Particularly, Chisholm emphasized her blackness and womanhood as pivotal in her decision to run for President, openly advocating for her marginalized status/identities as reasons to vote for her.

Negatively, on the other hand, Chisholm was affected by society’s negative proscription of being a black woman running for president. Like during her congressional tenure, Chisholm’s intersectional identities resulted in backlash and discrimination throughout the campaign. The lack of support from important feminist and black male political leaders negatively impacted Chisholm’s campaign. For instance, national feminist leader Gloria Steinem split her endorsement between Chisholm and George McGovern. Chisholm also encountered resistance from black men, voting not to endorse her campaign at the first-ever Black National Political Convention, which took place in 1972 in Gary, Indiana.

Chisholm was well-aware of how her marginalized status impacted her campaign. She stated:

“I’ve always met more discrimination for being a woman than for being black. When I ran for Congress, when I ran for President, I met more discrimination for being a woman than for being black. Men are men.”

Chisholm also openly discussed both the historic nature of her campaign as well as the way she was received by key black male leaders:

Nonetheless, Chisholm was fully supported by the Black Panther Party, which for the first time endorsed a presidential candidate. Gene Jones, a BPP member, said:

“The Black Panther Party puts forth a call, to every Black, poor and progressive human being across this country, to unite together to join Sister Shirley Chisholm’s campaign for election to the presidency of the United States.”

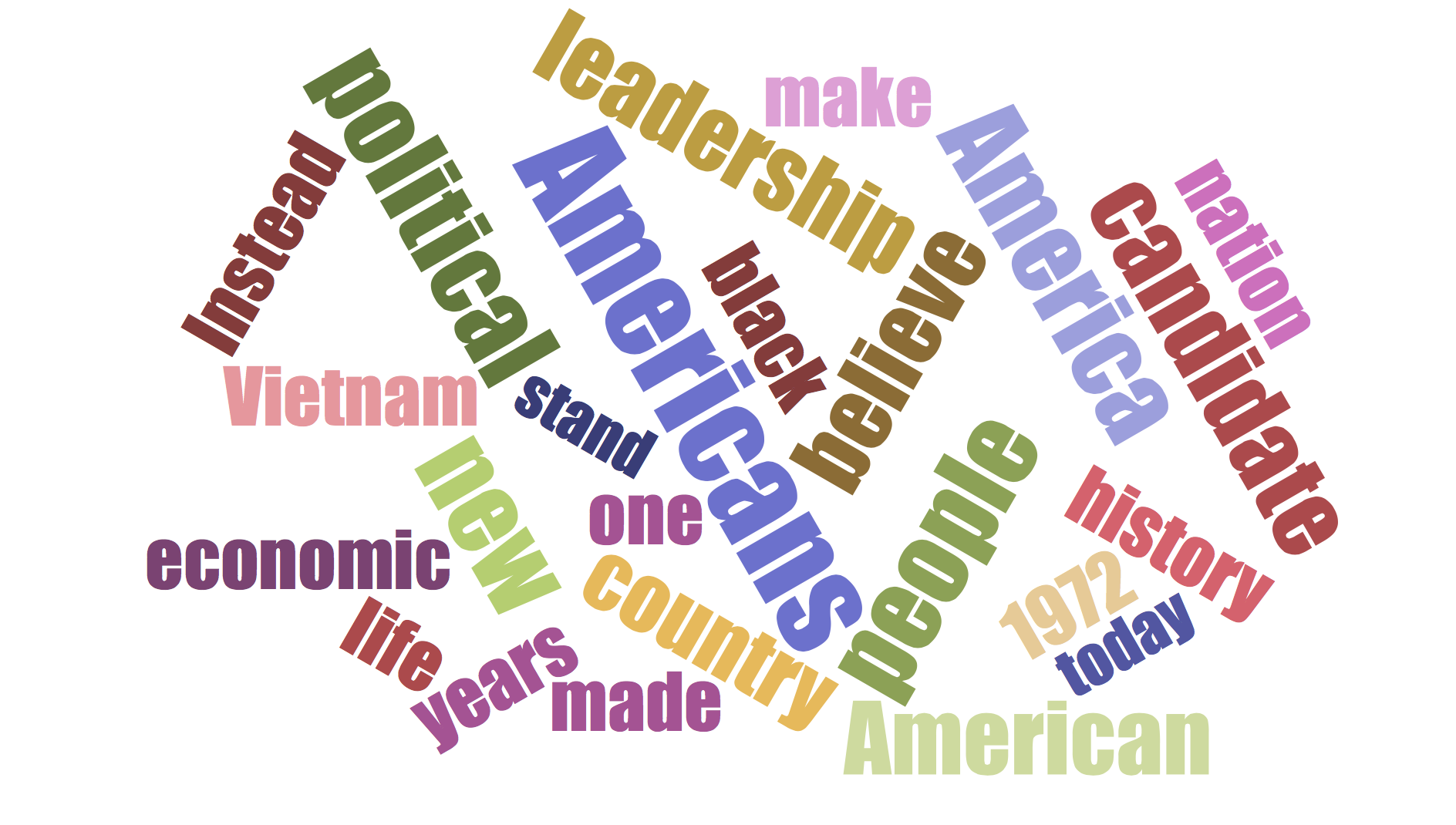

While, throughout her campaign, Chisholm did not run away from her black and woman identities, she highlighted a more general American identity. A word cloud analysis of her campaign announcement speech demonstrates that the words “Americans,” “American,” and “America” were the most utilized. The usage of words like “country,” “one,” and “nation” is also worth noting.

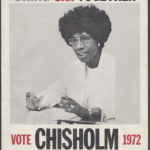

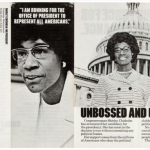

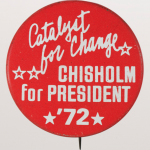

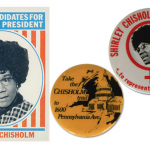

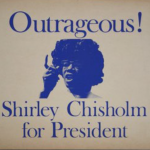

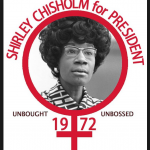

A review of her campaign materials demonstrates a similar trend. While Chisholm’s campaign emphasized her gender by repeatedly using the female symbol icon, they emphasized that Chisholm would “represent all Americans.” Outside of her classic “Unbought and Unbossed” slogan, the Chisholm 1972 presidential campaign also utilized the phrase “Bring U.S. together.” Here is a gallery of some of Chisholm’s 1972 campaign materials:

This trend demonstrates Chisholm’s ability to code-switch. Brittanica defines code-switching as “the process of switching from one linguistic code to another, depending on the social context.” In the case of Chisholm’s presidential campaign, she developed different messages to appeal to different constituencies of voters. Chisholm had done this in her past congressional campaigns, speaking Spanish to Spanish-speaking voters.

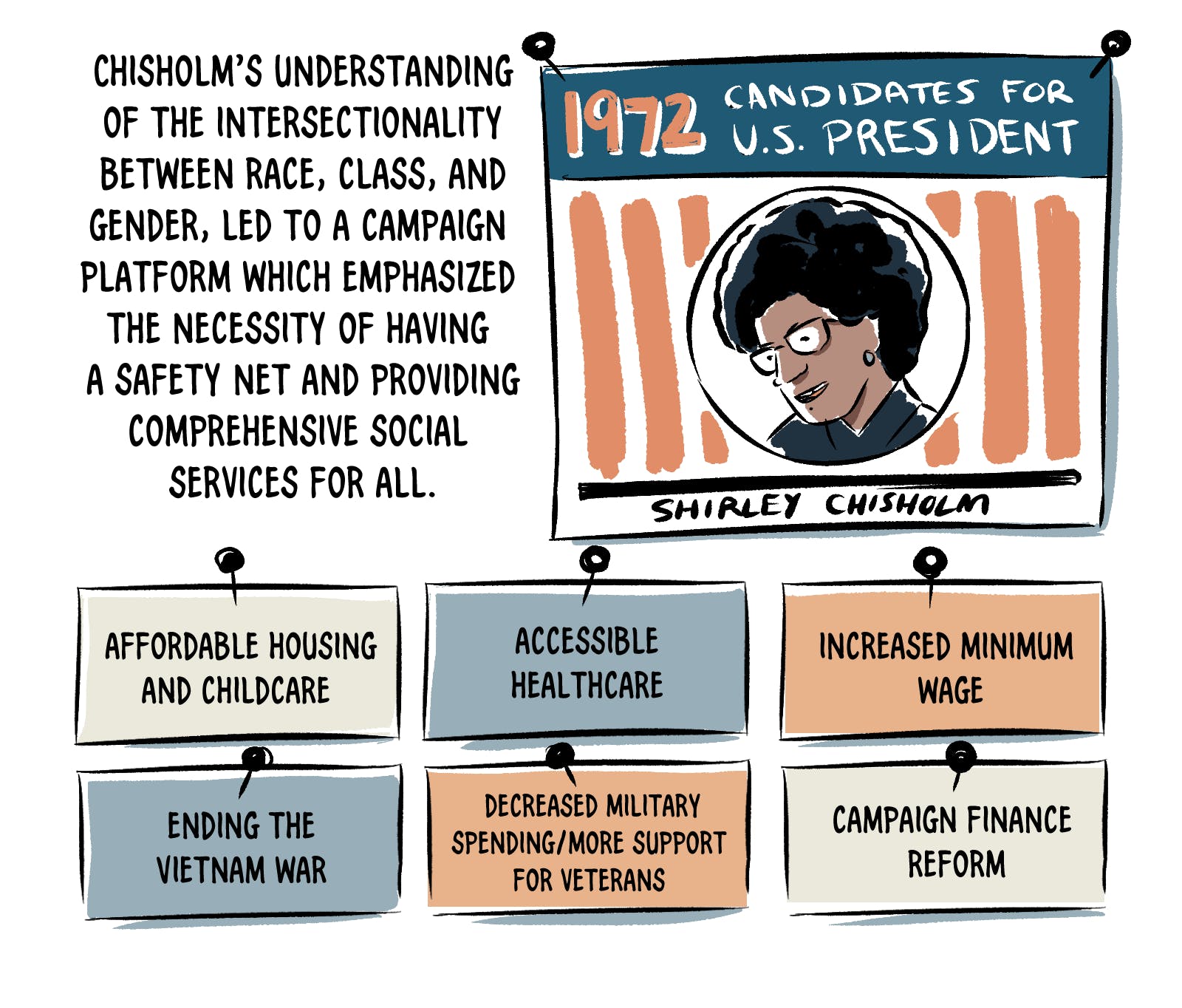

Chisholm’s campaign platform emerged from her understanding of the intersectionality between class, gender, and race:

In the 1972 Democratic Presidential Primaries, Chisholm received over 430 thousand votes (2.7%), coming in fourth place with a total of 152 delegates. Chisholm won the popular vote in New Jersey and won a plurality of delegates in Louisiana and Mississippi.

In the 1972 Democratic Presidential Primaries, Chisholm received over 430 thousand votes (2.7%), coming in fourth place with a total of 152 delegates. Chisholm won the popular vote in New Jersey and won a plurality of delegates in Louisiana and Mississippi.

Without a doubt, Chisholm’s historic campaign left behind a notorious legacy that emphasized both intersectionality of identities as well as a more general “American” message. This formula was later utilized by other black female politicians in the United States.

Professor Tammy Brown’s examines Chisholm in the context of discourses of intersectional identities, arguing that Chisholm “effectively reconciled seemingly contradictory philosophies of racial, ethnic, and feminist pride with humanist and universalist ideals to win over a broad spectrum of voters.”

Chisholm’s intersectional identities surpassed gender and race. She was not only female and black, but also Barbadian-American, working class, a Spanish speaker, and the child of immigrants. As Matthew Wills puts it, given Chisholm’s several identities,

“She was able to privilege one identity over others depending on the political context, and seemed very aware that all these categories were historical constructs… Above all, Chisholm stood at a crossroads where civil rights, black power, women’s rights, anti-war, youth culture, and the Great Society all met.”

That’s how, as Brown argues, Chisholm’s appeal transcended exclusionary definitions of gender, race, and class “by emphasizing the common desire of all Americans to lead healthy and productive lives.” In other words, as demonstrated above, Chisholm’s campaign utilized a general “American” message that sought to reach voters of all identities without compromising her blackness and womanhood.

Many political scholars and pundits have sought to understand Chisholm’s legacy on the larger American political conversation, particularly regarding the electoral strategies of black women political candidates. Essence’s Taylor Crumpton evaluates Chisholm’s contributions as follows:

“Pioneers like Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress, initiated revolutionary change within a predominantly white-controlled political system that silenced intersectional individuals who challenged power structures and dynamics of oppression. Her famous mantra, “If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair,” heralded the unique role that Black women politicians have played in enacting social change as members of the federal government. Chisholm had the ability to defy generations of white male privilege through the weaponization of her voice and experiences as a Black woman.”

Nonetheless, while recognizing the incredible legacy of Chisholm’s congressional career and presidential campaign, scholars have a grimmer perspective about the positionality of Black women within the American political system. Duke University’s Paula McClain, Niambi Carter, and Michael Brady argued that “Black women have always occupied a tertiary position in the American hierarchy, primarily because Black women exist at the intersection of race and gender. As such, they have constituted a neglected and oftentimes invisible category.”

In comparing Chisholm’s presidential campaign with that of U.S. Senator Carol Moseley Braun – the first African American woman Senator in American history who ran for the Democratic Nomination for President in 2004 – McClain et al. found that some progress had been made in the 30 years that separated both campaigns. Particularly, Moseley Braun had raised more campaign donations and earned the endorsement of key feminist groups. However, the lack of support from race-based organizations for Moseley Braun’s campaign demonstrates that Black female politicians still have a long way to go.

In the 2020 presidential election, American voters will have another opportunity of electing a black female President. On January 21, 2019 – exactly 47 years after Chisholm announced her historic presidential candidacy – California Senator Kamala Harris launched her campaign for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States. On the campaign trail, Harris, the biracial daughter of Indian and Jamaican parents, has openly invoked Chisholm’s legacy. In fact, according to CBS news, “Harris paid homage to Chisholm’s historic campaign by using a similar color scheme and typography in her logo and promotional materials.”

It is clear that Chisholm’s commitment to staying true to her personal identities have outlived her. Chisholm remains a source of inspiration for millions of black women inside and outside of the United States, challenging those (mainly white men) who bash “Identity Politics” as the origin of all of our country’s problems.

Stacey Abrams, who almost became the first black female Governor in the country’s history but lost a very close and questionable race for Governor of Georgia in 2018, puts it best:

“…minorities and the marginalized have little choice but to fight against the particular methods of discrimination employed against them. The marginalized did not create identity politics: their identities have been forced on them by dominant groups, and politics is the most effective method of revolt.”

Chisholm’s Congressional Archives:

- Shirley Chisholm Campaign Poster – Bring U.S. Together

- Shirley Anita Chisholm – Painting

- Shirley Anita Chisholm Lapel Pin

- Rules Committee Photo

- Give Your Chair to a Lady

- Shirley Chisholm Ebony Magazine Cover

- Shirley Chisholm – Campaigning in MA

- Shirley Anita Chisholm – Talking to interns

- Permanent Interests: The Expansion, Organization, and Rising Influence of African Americans in Congress, 1971-2019

- Congresswomen’s Caucus – Organization Efforts

- Crafting an Identity on Capitol Hill

- Shirley Anita Chisholm – Photo

- Shirley Anita Chisholm – Lapel Pin

- The First African American Woman Elected to Congress

- Shirley Anita Chisholm – Portrait

- Yvette Clarke talks about Shirley Chisholm

- Whereas: Stories from the People’s House

- Congressional Black Caucus – History

Campaign Materials:

- Lapel Pin: President of All The People

- Lapel Pin: Catalyst for Change

- Lapel Pin: Shirley!

- Lapel Pin: “To represent all Americans”

- Shirley Chisholm Posters

- Outrageous! Shirley Chisholm for President – Poster

- THE PEOPLE’S CHOICE – Poster

- Leading the Way – Poster and two Lapel Pins

- Jump on the Chisholm Bandwagon

- 3 Shirley Chisholm for President Buttons

- Black and White poste

Videos:

- Shirley Chisholm: My Bid for Presidency

- Shirley Chisholm: The First Black Congresswoman

- Unbought and Unbossed: Chisholm’s fearless presidential run

- Chisholm declares Bid for President

- Senator Kamala Harris Presidential Campaign Launch in Oakland, CA

- Moseley Braun’s Presidential Campaign Announcement

Articles:

- Unbought and Unbossed: Why former Representative Shirley Chisholm (D-NY) deserves a permanent home in the United States Capitol

- Shirley Chisholm: A Catalyst for Political Change

- Unbought and Unbossed: Shirley Chisholm and the Voice of the People

- She Dared to be herself: Shirley Chisholm’s Legacy – Photo history

- Kamala Harris is among the few black women to run for President. Here is the amazing story of the first

- E Pluribus Unum? The Fight over Identity Politics

- “Tired of Going to Funerals”: The Black Political Convention in Gary

- A Look Back On Shirley Chisholm’s Historic 1968 House Victory

- Identity Politics

- Unbought and Unbossed: Long Before Hillary, There was Shirley Chisholm

- An Inspiration to Women Candidates in 2018: Remembering Shirley Chisholm

- ‘Unbought and Unbossed’: Shirley Chisholm’s feminist mantra is still relevant 50 years later

- Unbossed, Unbought, and Unheralded

- The battle over identity politics, explained

- Defining “Identity Politics”

- Kamala Harris’ campaign launch pays tribute to Shirley Chisholm’s 1972 run

- White People are experts at identity politics but complain when blacks, Latinos follow

- Encyclopedia of World Biography – Shirley Chisholm Biography

- Shirley Chisholm, ‘Unbossed’ Pioneer in Congress, is Dead at 80

- Panthers Endorse Shirley Chisholm

- The Significance of Shirley Chisholm’s Presidential Campaign

- The Legacy of Black Women Politicians

- Kamala Harris Launches Campaign for President

- GOP Adviser Slams Georgia’s Brian Kemp for Cheating and Undermining Democracy in Governor’s Race

Academic Articles